The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Chance for Himself, by J. T. Trowbridge

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: A Chance for Himself

or Jack Hazard and His Treasure

Author: J. T. Trowbridge

Release Date: March 16, 2018 [EBook #56759]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A CHANCE FOR HIMSELF ***

Produced by David Edwards, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from images made available by the

HathiTrust Digital Library.)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

| Chapter | Page | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | The Thunder-Squall | 7 |

| II. | What Jack found in the Log | 13 |

| III. | “Treasure-Trove” | 19 |

| IV. | In which Jack counts his Chickens | 28 |

| V. | Waiting for the Deacon | 32 |

| VI. | “About that Half-Dollar” | 36 |

| VII. | How Jack went for his Treasure | 41 |

| VIII. | Jack and the Squire | 49 |

| IX. | The Squire’s Perplexity and Jack’s Stratagem | 58 |

| X. | “The Huswick Tribe” | 65 |

| XI. | The “Court” and the “Verdict” | 70 |

| XII. | How Hod’s Trousers went to the Squire’s House | 78 |

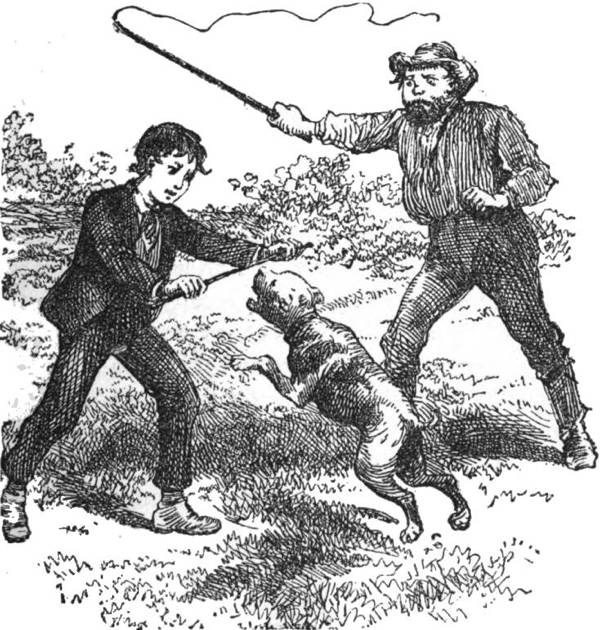

| XIII. | How Jack rescued Lion, but missed the Treasure | 82 |

| XIV. | Squire Peternot at Home | 89 |

| XV. | Jack and the Huswick Boys | 96 |

| XVI. | How Jack called at the Squire’s | 104 |

| XVII. | How Jack took to his Heels | 111 |

| XVIII. | How the Heels went Home without Shoes and Stockings | 116 |

| XIX. | How Jack was invited to ride | 122 |

| XX. | How the Shoes and Stockings came Home | 128 |

| XXI. | Jack in Disgrace | 135 |

| XXII. | Jack and the Jolly Constable | 143 |

| XXIII. | Before Judge Garty | 150 |

| XXIV. | The Prisoner’s Cup of Milk | 157 |

| XXV. | Jack’s Prisoners | 160 |

| XXVI. | The Owner of the Potato Patch, and his Dog | 167 |

| XXVII. | The Race, and how it ended | 174 |

| XXVIII. | The Search, and how it ended | 179 |

| XXIX. | The Culvert and the Cornfield | 187 |

| XXX. | Jack breakfasts and receives a Visitor | 194 |

| XXXI. | Tea with Aunt Patsy | 201 |

| XXXII. | A Starlight Walk with Annie Felton | 208 |

| XXXIII. | A Strange Call at a Strange Hour of the Night | 216 |

| XXXIV. | How Jack won a Bet, and returned a Favor | 221 |

| XXXV. | At Mr. Chatford’s Gate | 227 |

| XXXVI. | The “Ride” continued | 234 |

| XXXVII. | One of the Deacon’s Blunders | 239 |

| XXXVIII. | The Deacon’s Diplomacy | 246 |

| XXXIX. | A Turn of Fortune | 251 |

| XL. | The Squire’s Triumph | 257 |

| XLI. | How it all ended | 264 |

On a high, hilly pasture, occupying the northeast corner of Peach Hill Farm, a man and two boys were one afternoon clearing the ground of stones.

The man—noticeable for his round shoulders, round puckered mouth, and two large, shining front teeth—wielded a stout iron bar called a “crow,” with which he pried up the turf-bound rocks, and helped to tumble them over upon a drag, called in that region a “stun-boat.” The larger of the boys—a bright, active lad of about fourteen years—lent a hand at the heavy rocks, and also gathered up and cast upon the drag the smaller stones, on his own account. The second lad—nearly as tall, and perhaps quite as old as the other—helped a little about the stones, but divided his attention chiefly between the horse that drew the drag, and a shaggy black dog that accompanied the party.

“Come, boy!” said the man,—enunciating the m and b by closing the said front teeth upon his nether lip,—“ye better quit fool’n’, an’ ketch holt and help. ’S go’n’ to rain.”

“Ain’t I helping?” retorted the smaller boy. “Don’t I drive the horse?”

“A great sight,—long’s the reins are on his back, an’ I haf to holler to him half the time to git up an’ whoa. Git up, Maje! there! whoa!—Jack’s wuth jest about six of ye.”

“O, Jack’s dreadful smart! Beats everything! And so are you, Phi Pipkin!” said the boy, sneeringly. “You feel mighty big since you got married, don’t ye?—I bet ye Lion’s got a squirrel under that big rock! I’m going to see!” And away he ran.

“That ’ere Phin Chatford ain’t wuth the salt in his porridge,—if I do say it!” remarked Mr. Pipkin. “I never did see sich a shirk; though when he comes to tell what’s been done, you’d think he was boss of all creation. Feel as if I’d like to take the gad to him sometimes, by hokey!”

“O Jack!” cried Phin, who had mounted a boulder much too large for Mr. Pipkin’s crow-bar, “you can see Lake Ontario from here,—’way over the trees there! Come and get up here; it’s grand!”

“I’ve been up there before,” replied Jack. “Haven’t time now. We shall have that shower here before we get half across the lot.”

“Come, Phin!” called out Mr. Pipkin, “there’s reason in all things! We’ll onhitch soon’s we git this load, an’ dodge a wettin’.”

“Seems to me you’re all-fired ’fraid of a wetting, both of ye,” cried Phin. “’T won’t hurt me! Let it come, and be darned to it, I say!”

This last exclamation sounded so much like blasphemy to the boy’s own ears, and it was followed immediately by so vivid a flash of lightning and so terrific a peal of thunder, from a black cloud rolling up overhead, that he jumped down from the rock and crouched beside it, looking ludicrously pale and scared; while the dog, dropping ears and tail, and whining and trembling with fear, ran first for Jack’s legs, then for Mr. Pipkin’s, and finally crouched by the boulder with Phin.

“You’re a perty pictur’ there!” cried Mr. Pipkin, with a loud, hoarse laugh. “Who’s afraid now?”

“Lion, I guess,—I ain’t,” said Phin, with an unnatural grin. “Only thought I’d sit down a spell.”

“It’s as cheap settin’ as standin’,—as the old hen remarked, arter she’d sot a month on rotten eggs, an’ nary chicken,” said Mr. Pipkin, whose spirits rose with the excitement of the occasion.

“There’s a good reason for the dog’s skulking,” said Jack. “He’s afraid of thunder, ever since Squire Peternot fired the old musket in his face and eyes. Hello! another crack!”

“I never see sich thunder!” exclaimed Mr. Pipkin. “Look a’ them rain-drops! big as bullets!”

“It’s coming!” cried Jack; and instantly the heavy thunder-gust swept over them.

“Onhitch!” roared out Mr. Pipkin, in the sudden tumult of rain and wind and thunder. “I must look out for my rheumatiz! Put for the house!”

“We shall get drenched before we are half-way to the house,” replied Jack, dropping the trace-chains. “I go for the woods!”

“I’ll take Old Maje, then,” said Mr. Pipkin.

But before he could mount, Phin, darting from the imperfect shelter of the rock, ran and leaped across the horse’s back. As he was scrambling to a seat, holding on by mane and harness, kicking, and calling out, “Give me a boost, Phi!” Mr. Pipkin gave him a boost, and lost his hat by the operation. That was quickly recovered; but before the owner, clapping it on his head, could get back to the horse’s side, the youthful rider, using the gathered-up reins for a whip, had started for the barn.

“Whoa! hold on! take me!” bellowed Mr. Pipkin.

“He won’t carry double—ask Jack!”

Flinging these parting words over his shoulder, the treacherous Phin went off at a gallop, leaving Mr. Pipkin to follow, at a heavy “dog-trot,” over the darkened hill, through the rushing, blinding storm.

Jack was already leaping a wall which separated the pasture from a neighboring wood-lot. Plunging in among the reeling and clashing trees, he first sought shelter by placing himself close under the lee of a large basswood; but the rain dashed through the surging mass of foliage above, and trickled down upon him from trunk and limbs.

Looking hastily about to see if he could better his situation, he cast his eye upon a prostrate tree, which some former gale had broken and overthrown, and from which the branches had mostly rotted and fallen away. It appeared to be hollow at the butt, and Jack ran to it, laughing at the thought of crawling in out of the rain. He put in his head, but took it out again immediately. The cavity was dark, and a disagreeable odor of rotten wood, suggestive of bugs and “thousand-legged worms,” repelled him.

“Never mind!” thought he. “I can clap my clothes in the hole, and have ’em dry to put on after the shower is over.”

He stripped himself in a moment, rolled up his garments in a neat bundle, and placed them, with his hat and shoes, within the hollow log.

“Now for a jolly shower-bath!” And, seeing an opening in the woods a little farther on, he capered towards it, laughing at the oddness of his situation, and at the feeling of the rain trickling down his bare back. A few more lightning flashes and tremendous claps of thunder, then a steady, pouring rain for about five minutes, in which Jack danced and screamed in great glee,—and the storm was over.

“What a soaking Phi and Phin must have got!” thought he. “And now won’t they be surprised to see me come home in dry clothes!”

The wind had gone down before; and now a flood of silver light, like a more ethereal shower, broke upon the still woods, brightening through its arched vistas, glancing from the leaves, and glistening in countless drops from the dripping boughs. A light wind passed, and every tree seemed to shake down laughingly from its shining locks a shower of pearls. Jack was filled with a sense of wonder and joy as he walked back through the beautiful, fresh, wet woods to his hollow log. He waited only a minute or two for his skin to dry, and for the boughs to cease dripping; then put in his hand where he had left his clothes. His clothes were not there!

Jack was startled: in place of the anticipated triumph of going home in dry garments, here was a chance of his going home in no garments at all! Yet who could have taken them? how was it possible that they could have been removed during his brief absence? “Maybe this isn’t the log!” He looked around. “Yes, it is, though!”

No other fallen trunk at all resembling it was to be seen in the woods. Then he stooped again, and thrust his hand as far as he could into the opening. He touched something,—not what he sought, but a mass of hair, and the leg of some large animal. He recoiled instinctively, with—it must be confessed—a start of fear.

Jack’s first thought was, that the creature, whatever it might be, was in the log when he placed his clothes there, and that it had afterwards seized them and perhaps torn them to pieces. Then he reflected that the hair he touched felt wet; and he said, “The thing ran to its hole after I put the clothes in, and it has pushed ’em along farther into the log. Wonder what it can be!” It was evidently much too large for a raccoon or a woodchuck: could it be a panther? or a young bear? “He’s got my clothes, any way! I must get him out, or go home without ’em!”

Naked and weaponless as he was, he naturally shrank from attacking the strange beast; nor was it pleasant to think of going home in his present condition. It was not at all probable that Mr. Pipkin and Phin would return to their work that afternoon; and he was too far from the house to make his cries for help heard. He resolved to call, however.

“Maybe I can make Lion hear. I wonder if he went home.” He remembered that the frightened dog was last seen crouching with Phin beside the rock, and hoping he was there still, he began to call.

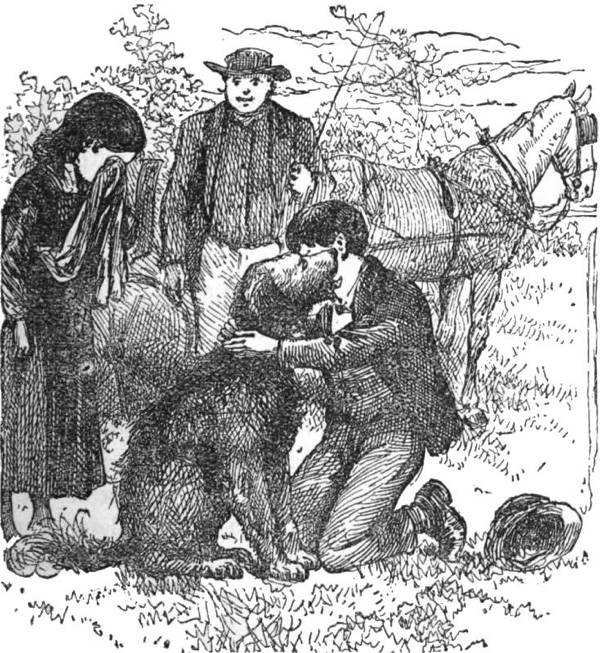

“Lion! here, Lion!” and, putting his fingers to his mouth, he whistled till all the woods rang. Then suddenly—for he watched the log all the while—he heard a tearing and rattling in the cavity, and saw that the beast was coming out. Stepping quickly backwards, he tripped over a stick; and the next moment the creature—big and shaggy and wet—was upon him.

“You rogue! you coward! old Lion! what a fright you gave me! what have you done with my clothes? you foolish boy’s dog!” For the beast was no other than Lion himself; frightened from his retreat beside the boulder, he had followed his young master to the woods, and crept into the hollow of the log, after Jack had left his clothes in it.

Jack returned to the log, and with some difficulty fished out his garments. He unfolded them one by one, holding them up and regarding them with ludicrous dismay. Lion had made a bed of them; and between his drenched hide and the rotten wood, they had suffered no slight damage.

“O, my trousers!” Jack lamented. “And just look at that shirt! I’d better have worn them in fifty showers! So much for having a dog that’s afraid of thunder!” And he gave the mischief-maker a cuff on the ear.

Jack recovered everything except one shoe, which he could not get without going considerably farther than he liked into the decayed trunk.

“Here, Lion! you must get that shoe! That’s no more than fair. Understand?” And showing the other shoe, he pointed at the hole.

In went Lion, scratching and scrambling, and presently came out again, bringing the shoe in his mouth. Encouraged by his young master’s approval, and eager to atone for his cowardice and the mischief he had done, he went in again, although no other article was missing, and was presently heard pawing and pulling at something deep in the log.

“After squirrels, maybe,” said Jack, as, dressing himself, he stepped aside to avoid the volleys of dirt which now and then flew out of the opening.

He thought no more of the matter, until the dog came backwards out of the hole, shook himself, and laid a curious trophy down by the shoe. Jack looked at it, and saw to his surprise that it was a metallic handle, such as he had seen used on the ends of small chests and trunks, or on bureau-drawers. He scraped off with his knife some of the rust with which it was covered, and found that it was made of brass. At the ends were short rusty screws, which, upon examination, appeared to have been recently wrenched out of a piece of damp wood.

“It’s a trunk-handle,” said Jack. “Lion has pulled it off. And the trunk is in the log!”

He grew quite excited over the discovery, and sent the dog in again for further particulars, while he hurriedly put on his shoes. Lion gnawed and dug for a while, and at last reappeared with a small strip of partially decayed board in his mouth.

“It’s a piece of the box!” exclaimed Jack. “Try again, old fellow!”

Lion plunged once more into the opening, and immediately brought out something still more extraordinary. It was a round piece of metal, about the size of an American half-dollar; but so badly tarnished that it was a long time before Jack would believe that it was really money. He rubbed, he scraped, he turned it over, and rubbed and scraped again, then uttered a scream of delight.

“A silver half-dollar, sure as you live, old Lion!”

The dog was already in the log again. This time he brought out two more pieces of money like the first, and dropped them in Jack’s hand.

“Here, Lion!” cried the excited lad. “I’m going in there myself!”

He pulled the dog away, and entered the cavity, quite regardless now of rotten wood, bugs, and “thousand-legged worms.” His heels were still sticking out of the log, when his hand touched the broken end of a small trunk, and slid over a heap of coin, which had almost filled it, and run out in a little stream from the opening the dog had made.

Out came Jack again, covered with dirt, his hair tumbled over his eyes, and both hands full of half-dollars. He dashed back the stray locks with his sleeve, glanced eagerly at the coin, looked quickly around to see if there was any person in sight, then examined the contents of his hands.

“If there’s no owner to this money, I’m a rich man!” he said, with sparkling eyes. “There ain’t less than a thousand dollars in that trunk!”

To a lad in his circumstances, five-and-twenty years ago, such a sum might well appear prodigious. To Jack it was an immense fortune.

“And how can there be an owner?” he reasoned. “It must have been in that log a good many years,—long enough for the trunk to begin to rot, any way. Some fellow must have stolen it and hid it there; and he’d have been back after it long ago, if he hadn’t been dead,—or like enough he’s in prison somewhere. Here, Lion! keep out of that!” and Jack cuffed the dog’s ears, to enforce strict future obedience to that command. “Nobody must know of that log,” he muttered, looking cautiously all about him again, “till I can take the money away.”

But now, along with the sudden tide of his joy and hopes, a multitude of doubts rushed in upon his mind. How was he to keep his great discovery a secret until he should be ready to take advantage of it? The thief who had stolen the coin might be dead; but was it not the finder’s duty to seek out the real owner and restore it to him? Already that question began to disturb the boy’s conscience; but he soon forgot it in the consideration of others more immediately alarming.

“The thief may have been in prison, and he may come back this very night to find his booty! Or the owner of the land may claim it, because it was found on his premises.” And Jack remembered with no little anxiety that the land belonged to Mr. Chatford’s neighbor, the stern and grasping Squire Peternot. “Or, after all,” he thought, “it may be counterfeit!”

That was the most unpleasant conjecture of any. “I’ll find out about that, the first thing,” said Jack; and he determined to keep his discovery in the meanwhile a profound secret.

Accordingly, after due deliberation, he crept back into the log, and replaced the piece of the trunk, with the handle, and all the coin except one half-dollar; then, having partially stopped the opening with broken sticks and branches, he started for home.

Taking a circuitous route, in order that, if he was seen emerging from the woods, it might be at a distance from the spot where his treasure was concealed, Jack came out upon the pasture, crossed it, took the lane, and soon got over the bars into the barn-yard. As he entered from one side he met Mr. Pipkin coming in from the other.

“Hullo!” he cried, with a wonderfully natural and careless air, “did ye get wet?”

“Yes, wet as a drownded rat, I did! So did Phin,—and good enough for him, by hokey!” said Mr. Pipkin. “Where’ve you been?”

“O, I went into the woods. Got wet, though, a little; and dirty enough,—just look at my clothes!”

“I’ve changed mine,” remarked Mr. Pipkin. “Wasn’t a rag on me but what was soakin’ wet. I wished I had gone to the woods.”

“I’m glad ye didn’t,” thought Jack, as he walked on. “O,” said he, turning back as if he had just thought of something to tell, “see what I found!”

“Half a dollar? ye don’t say! Found it? Where, I want to know!” said Mr. Pipkin, rubbing the piece, first on his trousers, then on his boot.

“Over in the woods there,—picked it up on the ground,” said Jack, who discreetly omitted to mention the fact that it had first been laid on the ground by Lion.

“That’s curi’s!” remarked Mr. Pipkin.

“What is it?” said Phin, making his appearance, also in dry garments. He looked at the coin, while Jack repeated the story he had just told Mr. Pipkin; then said, with a sarcastic smile, “Feel mighty smart, don’t ye, with yer old half-dollar! I don’t believe it’s a good one.” And Master Chatford sounded it on a grindstone under the shed. “Couldn’t ye find any more where ye found this?”

“What should I want of any more, if this isn’t a good one?” replied Jack. “Here! give it back to me!”

“’Tain’t yours,” said Phin, with a laugh, pocketing the piece, and making off with it.

“It’s mine, if I don’t find the owner. ’Tisn’t yours, any way! Phin Chatford!”—Phin started to run, giggling as if it was all a good joke, while Jack started in pursuit, very much in earnest. “Give me my money, or I’ll choke it out of ye!” he cried, jumping upon the fugitive’s back, midway between barn and house.

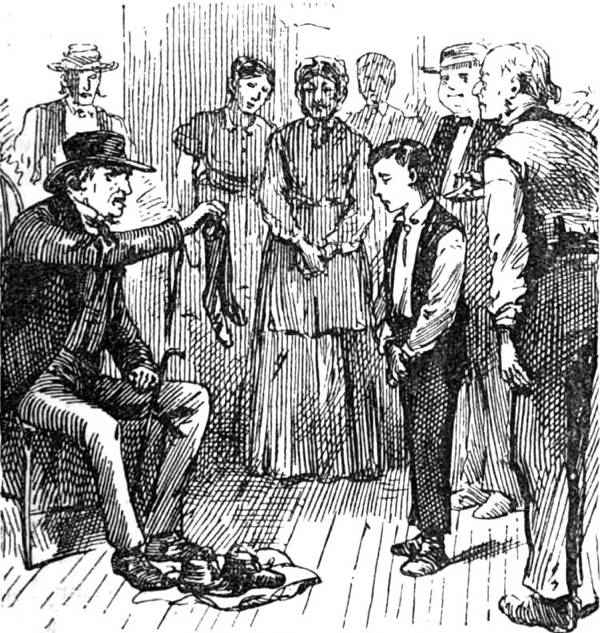

“Here, here! Boys! boys!” said a reproving voice; and Phin’s father, coming out of the wood-shed, approached the scene of the scuffle. “What’s the trouble, Phineas? What is it, Jack?”

“He’s choking me!” squealed Phineas.

“He’s got my half-dollar!” exclaimed Jack, without loosing his hold of Phin’s neck.

“Come, come!” said Mr. Chatford. “No quarrelling. Have you got his half-dollar?”

“Only in fun. Besides, ’tain’t his”; and Phin squalled again.

“Let go of him, Jack!” said Mr. Chatford, sternly. Jack obeyed reluctantly. “Now what is it all about?”

“I’ll tell ye, deacon!” said round-shouldered Mr. Pipkin, coming forward. “It’s an old half-dollar Jack found in the woods; Phin snatched it and run off with ’t. Jack was arter him to git it back; he lit on him like a hawk on a June-bug; but he ha’n’t begun to give him the chokin’ he desarves!”

“Give me the money!” said the deacon. “No more fooling, Phineas!”

“Here’s the rusty old thing! ’Tain’t worth making a fuss about, any way,” said Phin, contemptuously. “Ho! Jack! you don’t know how to take a joke!”

“You do know how to take what don’t belong to you,” replied Jack. “Is it a good one, Mr. Chatford? That’s what I want to know.”

“Yes, I guess so,—I don’ know,—looks a little suspicious. Can’t tell about that, though; any silver money will tarnish, exposed to the damp. I’ll ring it. Sounds a little mite peculiar. Who’s got a half-dollar?”

“I have!” cried Phin’s little sister Kate.

In a minute her piece was brought, and Jack’s was sounded beside it on the door-stone; Jack listening with an anxious and excited look.

SOUNDING THE HALF-DOLLAR.

“No, it don’t ring like the other,” observed the deacon. Jack’s heart sank. “Has a more leaden sound.” His heart went down into his shoes. “It may be good, though, after all.” It began to rise again. “We can’t tell how much the rust has to do with it. Shouldn’t wonder if any half-dollar would ring a little dull, after it had been lying out in the woods as long as this has.” And Jack’s spirits mounted again hopefully. “I’m going over to the Basin to-night,” concluded the deacon. “I’ll take it to the watch-maker, and have him test it, if you say so.”

“I wish you would,” said Jack. “And—I’d like to know who it belongs to.”

“That’s right; of course you don’t want it if it’s a bad one, or if you can find the real owner to it.”

“I meant,” faltered Jack,—“of course I wouldn’t think of passing counterfeit money, and I don’t want another man’s money any how,—but—I found it on somebody’s land. Now I’d like to know if—that somebody—has any claim to it, on that account.”

“I don’t think he’d be apt to set up a claim, without he was a pretty mean man,” said the deacon.

“Not even if ’twas Squire Peternot?” said Mr. Pipkin. “Guess he’d put in for his share, if there was any chance o’ gittin’ on ’t!”

“Nonsense, Pippy! If ’twas a large sum, he might, but a trifle like this,—you’re unjust to the squire, Pippy.”

“I haven’t said it was the squire’s land. But suppose it was? And suppose it had been a large sum,” queried Jack, “could he claim it? What’s the law?” And, to explain away his extraordinary interest in the legal point, he added, laughingly, “Just for the fun of it, I’d like to know what he could do if he should try Phin’s joke, and set out to get my half-dollar away!”

“I really don’t know about the law,” the deacon was saying, when Lion barked. “Hist! here comes Peternot himself! Say nothing. I’ll ask him. He’s bringing his nephew over to see us.”

“He’s kind of adopted his nephew, hain’t he, sence he heard of his son’s death?” said Mr. Pipkin. “I’ve seen him hangin’ around there.”

“No; he only wants to get him into our school next winter.”

“Ho! a schoolmaster!” whispered Phin, jeering at the new-comer. “Say, Jack! I bet we can lick him!”

“Don’t look as if he had any more backbone ’n a spring chicken,” was Mr. Pipkin’s unfavorable criticism, as the gaunt and limping squire came to the door with his young relative.

“Good afternoon, neighbor,” said the deacon, shaking hands first with the uncle, then with the nephew. “You’ve come just at the right time. We’ve a legal question to settle. Suppose Jack, here, finds a purse of money on my place; no owner turns up; now whose purse is it, Jack’s or mine?”

“Your land—your hired boy—I should say, your purse,” said the squire, emphatically.

“But suppose you find such a purse on my land?”

“H’m! that alters the case. How is it, Byron? My nephew is studying law; he can tell you better than I can about it.”

Peternot thought this a good chance to bring the candidate for the winter’s school into favorable notice; and the candidate for the winter’s school made the most of his opportunity. He was a slender young man with a sallow complexion, a greenish eye, a pimpled forehead, and a rather awkward and studied manner of speaking. In rendering his opinion he was as prolix as any judge on the bench. He began with a disquisition on the nature of law, and finally, coming down to the case in point, said it would be considered a case of treasure-trove.

“What’s that?” Jack eagerly interrupted him.

“Treasure-trove is treasure found.”

“Then why don’t they say treasure found?”

“’Sh, boy!” said Mr. Chatford, good-naturedly, smiling at the youngster’s impatience of long-winded sentences and large words. “What’s the law of—treasure-trove, I believe you call it, Mr. Dinks?”

“I don’t think there’s any law on the subject,” replied the student of Blackstone, picking his teeth with a straw.

“No law! then how can such a case be decided?”

“Custom, which makes a sort of unwritten law, would here come in.”

“Well, what’s the custom?”

Thereupon Mr. Byron Dinks became prolix again, speaking of English custom, which, like English law, creates precedents for our own country. The meaning of his discourse, stripped of its technical phrases and tedious repetitions, seemed to be, that formerly, treasure-trove went to the crown; that in more modern times it was divided—in a case like this—between the finder and the man on whose premises it was found; but that he didn’t think any precedent had been established in America.

“We’re about as wise now as we were before,” remarked Phin’s elder brother Moses, standing in the kitchen door.

Mr. Chatford gave him a wink to remain silent, and said, “How are we to understand you, Mr. Dinks? To use your own expression, A finds money on B’s premises; now what would be your advice to B?”

“Supposing B is my client? I should advise him to get possession of the money, if he could. Possession is nine points of the law.”

“Well, but if he couldn’t get possession?”

“Then try to compromise for one half. Then for a quarter. Then for what he could get.”

“Very good. Now what would be your advice to A?”

“A is my client?”

“Yes, we’ll suppose so.”

Spitting and throwing away his straw, Mr. Byron Dinks said with a laugh, “My advice to A would be to pocket the money and say nothing about it; keep possession, any way; fight for it.”

“Thank you,” said the deacon, with quiet irony in his tones. “Now we know what the law is on this subject, boys.”

“I don’t see, for my part, that it differs very much from common sense,” remarked the simple-minded Mr. Pipkin, “only it takes more words to git at it.”

“I’m sure,” said the squire, “my nephew has given you all the law there is to govern such cases, and good advice to his clients. ’T ain’t his fault if people can’t understand him.”

“I guess we all understand the main point, now we’ve got at it,” said Deacon Chatford. “Hang on to your money, Jack.”

“You’ve got it,” said Jack, more deeply glad and agitated than any one suspected.

“So I have. Well, I’ll tell ye when I get home from the Basin to-night whether it’s good or not. Walk in, gentlemen.”

And the deacon entered the house with his guests.

Peternot and his nephew took their departure, after making a short call. Then the family sat down to the supper-table, and the merits and prospects of the candidate for the winter’s school were discussed in a manner that ought to have made his ears tingle. Then, while the boys harnessed the mare and brought her to the door, the deacon changed his clothes, and at last started for the Basin.

“Don’t forget to ask about that half-dollar!” said Jack, as he held the gate open for the buggy to pass through.

“Glad you reminded me of it,—I should have forgotten it,” replied the notoriously absent-minded deacon.

Jack wished he could have found some excuse for going with him, but he could not think of any.

“How can I wait till he gets back, to know about it?” thought he, as he stood at the gate and watched the buggy and Mr. Chatford’s black hat disappear over the brow of the hill.

His revery was interrupted by Moses, who, noticing the boy’s unusual conduct,—for Jack was ordinarily no dreamer when there was work to be done,—called out to him from the stable-door, “Say, Jack! you’ve got to go and fetch the cows to-night; Phin says he won’t.”

“It’s Phin’s turn,—but I don’t care, I’ll go.” And Jack set off for the pasture, glad of this opportunity to be alone, and to muse upon his wonderful discovery.

It was a beautiful evening. The air was fresh and cool, and perfectly delicious after the shower. The sky overhead was silver-clear, but all down the gorgeous west, banks and cliffs and floating bars of cloud burned with the hues of sunset. Jack’s heart expanded, as he walked up the lane; and there, in that lovely atmosphere, he built his airy castles.

“If I am a rich man,” thought he, “what shall I do with my money? I’ll put it out at interest for a year or two,—I wonder how much there is! That’ll help me get an education. Then I’ll go into business, or buy a little place somewhere, and I’ll have my horses and wagons and hired men, and—” O, what a vision of happiness floated before his eyes! riches, honors, friendships, and in the midst of all the sweetest face in the world,—the face of his dearest friend, Mrs. Chatford’s niece, Annie Felton.

Then he looked back wonderingly upon his past life. “I can hardly believe that I was nothing but a mean, ragged, swearing little canal-driver only a few months ago. Over yonder are the woods where the charcoal-burners were, that I wanted to hire out to, after I had run away from the scow,—the idea of my hiring out to them! Now here I am, treated like one of Mr. Chatford’s own boys, and—with all that money, if it is money,” he added, his heart swelling again with misgivings. “Go, Lion! go for the cows,” he said; and he himself began to run, calling by the way, “Co’, boss! co’, boss!” as if bringing the cows would also bring Mr. Chatford home, with his report concerning the half-dollar.

“He won’t be there, though, for an hour or two yet,” he reflected. “What’s the use of hurrying? I shall only have the longer to wait. I wonder if that log is just as I left it!” For Jack had still a secret dread lest the unknown person who had hidden the treasure so many years ago should now suddenly return and carry it away. “I’ll cut over there and take just one peep,” he said.

So, having started the cattle upon their homeward track, with Lion barking after the laggards, Jack leaped a fence, ran across the lot where he had been at work that afternoon with Mr. Pipkin and Phin when the shower surprised them, and was soon standing alone by the log in the darkening woods. The sticks which he had stuffed into the end of the hollow trunk were all in their place. And yet it seemed a dream to Jack, that he had actually found a box of money in that old tree,—that it was there now! He wanted to pull out the sticks and go in and make sure of his prize, but forbore to do so foolish a thing.

“Of course it’s there,” thought he. “And I’m going to take care that nobody knows where it is, till I’ve got it safe in my own possession; then who can say whether I found it on Mr. Chatford’s, or Squire Peternot’s, or Aunt Patsy’s land, if I don’t tell? Let Squire Peternot claim it if he can!”

Yet Jack longed to tell somebody of his discovery. “O, if I could only tell Annie Felton, and get her advice about it!” But Annie, who taught the summer school, and “boarded around,” was just then boarding in a distant part of the district. The next day, however, was Saturday; then she would come home to her aunt’s to spend the Sunday, and he could impart to her his burning secret.

Jack stayed but a minute in the woods, then, hurrying back, rejoined Lion, who was driving the cows into the lane. Arrived at the barn-yard, he took one of three or four pails which Mr. Pipkin had brought out from the pantry, and a stool from the shed, and sat down to do his share of the milking. He had always liked that part of the day’s work well enough before; but now with a secret feeling of pride and hope he said to himself, “Maybe I sha’n’t always be obliged to do this for a living!” And he wondered how it would seem to be a gentleman and live without work.

The milk was carried to the pantry and strained; the candles were lighted, and the family sat in a pleasant circle about the kitchen table, while, without, the twilight darkened into night, and the crickets sang. There was Mr. Pipkin showing Phin how to braid a belly into his woodchuck-skin whiplash; Mrs. Pipkin (late Miss Wansey) paring a pan of apples, which she held in her lap; Moses reading the “Saturday Courier,” a popular story-paper in those days; little Kate, sitting on a stool, piecing a bed-quilt under her mother’s eye,—sewing together squares of different colored prints cut out from old dresses, and occasionally looking up to ask the maternal advice,—while Mrs. Chatford was doing some patch-work of a different sort, which certain rents in Phin’s trousers rendered necessary. Jack sat in the corner, silent, and listening for buggy-wheels.

“I hope you won’t go climbing over the buckles and hames, on to a horse’s back, in that harum-scarum way, another time,” said the good woman, in tones of mild reproof, to her younger son.

“’T was beginning to rain, and I couldn’t stop to think,” said Phin, laughing. “Could I, Phi?”

“I should think not, by the hurry you was in to hook my ride,” replied Mr. Pipkin, with reviving resentment. “That was a mean trick; and now jes’ see how I’m payin’ ye for it! Ye never could ’a’ got a decent-lookin’ belly into this lash, in the world, if ’twa’n’t for me.”

“That’s ’cause you’re such a good feller, and know so much!” said Phin, who could resort to flattery when anything was to be gained by it. “O, look, Mose! ain’t Phi doing it splendid? It’s going to be the best whiplash ever you set eyes on.”

Mr. Pipkin’s lips tightened in a grin around his big front teeth, and he worked harder than ever drawing the strands over the taper belly, while Phin, leaning over the back of his chair, whispered to Jack, “See what a fool I can make of him!”

At that Mrs. Pipkin, who had a keen ear and a sharp temper, flared up.

“Mr. Pipkin!”

“What, Mis’ Pipkin?”—meekly.

“You’ve worked long enough on that whiplash. He’s making fun of ye; and that’s all the thanks you’ll ever get for helping him. Take hold here and pare these apples while I slice ’em up.”

“In a minute. I can’t le’ go here jes’ now,” said Mr. Pipkin.

Whereupon Mrs. Pipkin laid down her knife and the apple she was paring, and looked at her husband over the rim of the pan in perfect astonishment.

“Mr. Pipkin! did you hear my request?”

“Yes, I heerd ye, but—”

“Mr. Pipkin,” interrupted Mrs. Pipkin, severely, “will you have the kindness to pare these apples? I don’t wish to be obliged to speak again!”

“What’s the apples fer,—sass?” said Mr. Pipkin, mildly.

“Pies; and you know you’re as fond of pies as anybody, Mr. Pipkin.”

“Wal, so I be, your pies. I declare, you do beat the Dutch with your apple-pies, if I do say it. There, Phin, I guess you can go along with the belly now. If it’s for pies, I’ll pare till the cows come hum!”

Thus disguising his obedience to his wife’s request, Mr. Pipkin took the pan and the knife, and Mrs. Pipkin recovered from her astonishment.

“Jack might pare the apples and let Phi braid!” Phin complained, getting into difficulties with his whiplash. “Darn this old belly!” And he flung it across the room.

“Phineas! you shall go to bed if I hear any more such talk,” said Mrs. Chatford, as sternly as it was in her kind motherly nature to speak. Then looking at Jack in the corner, “How happens it you are not reading your book to-night? It’s something new for you to be idle.”

“O, I don’t feel much like reading to-night,” said Jack, whose heart was where his treasure was.

“He’s thinking about his half-dollar, waiting to know if it’s a good one,” sneered Phin.

“Shouldn’t wonder if that half-dollar had dropped out of old Daddy Cobb’s money-box,” remarked Mr. Pipkin, taking a slice of apple.

“Mr. Pipkin! these apples are for pies!” said Mrs. Pipkin, in a warning voice.

“Daddy Cobb’s money-box! what’s that?” faltered Jack, fearing he had found an owner to the coin.

“What! didn’t ye never hear tell about Daddy Cobb’s diggin’ for a chist o’ treasure? Thought everybody’d heerd o’ that. There’s some kind o’ magic about it, hanged if I can explain jest what. The chist has a habit o’ shiftin’ its hidin’-place in the ground, so that though Daddy’s a’most got holt on ’t five or six times, it has allers slipped away from him in the most onaccountable and aggravatin’ manner. He has a way o’ findin’ where it is, by some hocus-pocus, hazel-wands for one thing; then he goes with his party of diggers at night,—for there’s two or three more fools big as him,—and they make a circle round the place, and one reads the Bible and holds the lantern while the rest dig, and if nobody speaks or does anything to break the charm, there’s a chance ’at they may git the treasure. Once Daddy says they had actooally got a holt on’t,—a big, square iron chist,—but jest’s they was liftin’ on’t out he jammed his finger, and said ‘Oh!’ and by hokey! if it didn’t disappear right afore their face an’ eyes quicker ’n a flash o’ lightnin’!”

Jack listened intently to this story. He did not believe that his treasure was the one Daddy Cobb had been digging for so long, but might it not elude his grasp in the same way?

At every sound of wheels Jack started; and more than once he imagined he heard a wagon stop at the gate. Still no deacon; would he never return? Jack watched the clock, and thought he had never seen the pointers move so slowly.

Three or four times he went to the door to listen; and at last he walked down to the gate. It was bright, still moonlight, only the crickets and katydids were singing, and now and then an owl hooted in the woods or a raccoon cried.

“There’s a buggy coming!” exclaimed Jack. He could hear it in the distance; he could see it dimly coming down the moonlit road. “It’s Mr. Chatford!” He knew the deacon’s peculiar “Ca dep!” (get up) to the horse.

“That you, Jack?” said the deacon, driving in.

“Yes; thought I’d come down and shut the gate after you,” replied Jack.

Mr. Chatford stopped at the house, and Jack ran to help him take out some bundles. Then the deacon drove on to the barn, and Jack hurried after him. Still not a word about the half-dollar.

“You can go into the house; I’ll take care of Dolly,” said Jack.

“I’ll help; ’t won’t take but a minute,” said Mr. Chatford. “I’ve got bad news for you.”

“Have you?” said Jack, with sudden faintness of heart. “What?”

“For you and Lion,” added the deacon. “Duffer’s got another dog. He made his brags of him to-night. Said he could whip any dog in seven counties.”

“He’d better not let him tackle Lion!” said Jack.

“I told him I hoped he wouldn’t kill sheep, as his other dog did. Take her out of the shafts; we’ll run the buggy in by hand.”

The broad door of the horse-barn stood open. Jack led the mare up into the bright square of moonshine which lay on the dusty floor. There the harness was quickly taken off. Not a word yet concerning the half-dollar, which Jack was ashamed to appear anxious about, and which he began to think Mr. Chatford, with characteristic absent-mindedness, had forgotten.

“By the way, I’ve good news for you!” suddenly exclaimed the deacon.

Jack’s heart bounded. “Have you?”

“I saw Annie over at the Basin. She wants to go home to her folks to-morrow. Would you like to drive her over? She spoke of it.”

“And stay till Monday?” said Jack, to whom this would indeed have been good news at another time.

“Yes; start early, and get back Monday morning in time for her to begin school. Then she won’t go home again till her summer term is out.”

“Maybe—I’d better—wait and go then.” Jack felt the importance of early securing his treasure, and, having set apart Sunday afternoon for that task (“a deed of necessity,” he called it to his conscience), he saw no way but to postpone the long-anticipated happiness of a ride and visit with his dear friend. Yet what if the treasure were no treasure?

“As you please,” said the deacon, a little surprised at Jack’s choice. “Moses will be glad enough to go. See that she has plenty of hay in the rack, and don’t tie the halter so short as you do sometimes. Now give me a push here,”—taking up the buggy-shafts.

“Oh!” said Jack, as if he had just thought of something,—“I was going to ask you—about that half-dollar?”

“I didn’t think on ’t,” said Mr. Chatford, standing and holding the shafts while Jack went behind,—“not till I’d got started for home. Then I put my hand in my pocket for something, and found your half-dollar. Help me in with the buggy, and then I’ll tell you.”

The deacon drew in the shafts, Jack pushed behind, and the buggy went rattling and bounding up into its place.

“Did you go back?” asked Jack, out of breath,—not altogether from the effort he had just made.

The deacon deliberately walked out of the barn, and carefully shut and fastened the door; then, while on the way to the house, he explained.

“I had paid for my purchases out of my pocket-book, or I should have found that half-dollar before. However, as I had promised you, I whipped about and drove back to the goldsmith’s. He was just shutting up shop. I told him what I wanted. He went behind his counter, lit a lamp, looked at your half-dollar, cut into it, and then flung it into his drawer.”

“Kept it!” gasped out Jack.

“Yes; ’t was as good a half-dollar as ever came from the mint, he said. He gave me another in its place.”

Jack could not utter a word in reply to this announcement, which, notwithstanding his utmost hopes, astonished and overjoyed him beyond measure. As soon as he had recovered a little of his breath and self-possession, he grasped the deacon’s arm, and was on the point of exclaiming, “O Mr. Chatford! I have found a trunk full of just such half-dollars as that!”—for he felt that he must tell his joy to some one, and to whom else should he go? But already the deacon’s other hand was on the latch of the kitchen door, which he opened; and there sat the family round the table within.

“What is it, my boy?” said Mr. Chatford, as Jack shrank back and remained silent. “Oh! you want your half-dollar. Of course!” putting his hand into his pocket.

“I don’t care anything about that,” said Jack. He took it, nevertheless,—a bright, clean half-dollar in place of the scratched and tarnished coin he had given Mr. Chatford that afternoon.

Mr. Chatford stood holding the door open.

“Ain’t you coming in?”

“No, sir,—not just yet.”

Jack felt that he must be alone with his great, joyful, throbbing thoughts for a little while; and he wandered away in the moonlit night.

In the forenoon of the following day Annie Felton dismissed her little school half an hour earlier than she was accustomed to do, and went to her Aunt Chatford’s house, to dine with her relatives and prepare for the long afternoon’s ride. She was greatly surprised when told that Jack was not to accompany her.

“Did Uncle Chatford speak to him about it?” she inquired of her aunt.

“Yes, but for some reason he didn’t seem inclined to go. That just suited Moses; he was glad enough of the chance.”

“Jack has found a half-dollar, and it has just about turned his head,” remarked Mrs. Pipkin.

“A half-dollar?” repeated Annie, wondering if such a trifle could indeed have so affected her young friend. No, she could not believe it. Then why had he willingly let slip an opportunity which she had thought he would be eager to seize?

Soon the men and boys came in to dinner,—Moses in high spirits, and with his Sunday clothes on; Jack jealous and unhappy.

“Why didn’t I leave that till another Sunday? or get it one of these moonlight nights?” he said to smile, and moved her lips with some sweet, inaudible meaning as she passed him; but Moses, good fellow though he was, cast upon him a look of contempt, and flourished his whip, driving proudly away beside his beautiful cousin.

“IT’S A GREAT SECRET.”

Jack, much as he thought of his hidden treasure, now for the first time in his life felt the utter worthlessness of money compared with the good-will and companionship of those we love,—a truth which it takes some of us all our lives to discover.

The sight of Annie Felton always stirred the nobler part of his nature; and now, going back to the house, he began to blame himself for having taken hitherto a purely selfish view of his treasure.

“All I’ve thought of has been just the good it was going to do me!” And he said to himself that he didn’t deserve the good fortune that had befallen him. Now to bestow it all upon her he felt would be his greatest happiness.

“And give some to you, precious little Kate!” was his second thought, as the gay little creature came running with Lion to meet him. In like manner his benevolence overflowed to all,—even to sharp-tongued Mrs. Pipkin,—after Annie Felton had stirred the fountain.

Twenty-four hours seemed long to wait. But the time for securing his treasure at last came round. He walked to church in the morning with Phin and Mr. Pipkin, but, without saying a word to anybody of his intentions, he at noon came home alone across the fields. He found, as he expected, Mrs. Chatford keeping house.

“Why, Jack!” said she, “why didn’t you stay to Sunday school and the afternoon services?”

“Don’t you want to go this afternoon?” replied Jack, evasively. “There will be some of the neighbors riding by, who will carry you. I’ll take care of the house.”

“You are very kind to think of me,” she said. “But I don’t think of going. You’d better eat your luncheon, and go right back.”

Jack longed to tell her everything on the spot, but feared she might disapprove of his going to bring home the treasure on the Sabbath. “After all’s over, then she’ll say I did right,” thought he. So he remarked, carelessly, “There’s a new minister to-day; I don’t like him very well. I guess I’ll go over and see Aunt Patsy a little while this afternoon.”

“If you do, I’ll send a loaf of bread and one of the pies we baked yesterday,” said Mrs. Chatford.

This was what Jack expected; and it gave him an excuse for carrying a basket. He took off his Sunday clothes, putting on an every-day suit in their place, lunched, and soon after started with Lion. He made a brief visit to the poor woman, and then set out for home by way of the woods.

On the edge of Aunt Patsy’s wood-lot he paused and looked carefully all about him. Not a human being was in sight. A Sabbath stillness reigned over all the sunlit fields and shadowy woods. There were Squire Peternot’s cattle feeding quietly in the pasture. A hawk was sailing silently high overhead. As he turned and walked on, two or three squirrels, gray and black, ran along the ground, disappearing around the trunks of trees to reappear in the rustling tops, and it was all he could do to keep Lion still.

“Look here, old fellow!” said he, “remember, you are not to bark to-day!”

From Aunt Patsy’s wood-lot he entered the squire’s, stepping over a dilapidated fence of poles and brush. The snapping of the decayed branches broke the silence; then, as he listened, he heard, far off, the bells for the afternoon service begin to ring. It was a strange sound, in that wildwood solitude, so shadowy and cool, and full of the fresh odors of moss and fern.

The bells were still ringing, and their faint, slow, solemn toll filled Jack’s heart with an indefinable feeling of guilt as he reached the log where his treasure was, and reflected upon the very worldly business that brought him there.

He did not reflect long,—he was too eager for the exciting work before him. Having walked on to the farther edge of the woods, to see that nobody was approaching from that direction, he returned, and began to pull out the sticks which he had stuffed into the end of the log.

“Everything’s just as I left it, so far,” thought he. “Wonder if my money-chest will dodge a fellow, like old Daddy Cobb’s!”

The opening clear, he put on an old brown frock which he had brought in the basket, laid his hat and coat on the ground, told Lion to watch them, and entered the log headforemost. The treasure, too, was where he had left it. His body stopped the cavity so that he could see nothing in its depths, but his groping hand felt the little trunk and the coin that had fallen out of its broken end.

“I’ll take this loose money out of the way first,” thought he; “then maybe I can move the trunk.”

He had nothing but his pockets to put the coin into, and those his frock covered. “I’ll find something better,” thought he. Backing out of the log, he pulled off his shoes, and re-entered with one of them in his hand. This he filled with all the half-dollars he could find about the end of the trunk, which he then tried to move.

“It’s stuck in a heap of rotten stuff here,” he muttered, “and I shall break it more if I pull hard on it.” So he resolved to empty it where it was.

He was half-way out of the log, bringing after him his shoe freighted with coin, when he was startled by a sudden bark from Lion. Leaving his shoe, he tumbled himself out upon the ground in fearful haste, to find a stray calf in the bushes the innocent cause of alarm. For keeping guard too faithfully poor Lion got a box on the ear.

After waiting awhile, to see if anything more dangerous than the calf was nigh, Jack brought out his shoe, poured its rattling contents into the basket, which he covered with his coat, and then went back into the log. This time he took both shoes in with him, which he filled, and emptied one after the other into the basket. Another journey, another, and still another, and he began to think there was more coin than he could carry home.

“I can get it away from here, though, so nobody can tell on whose land I found it,”—which he seemed to think a very important point to gain. “I’ll leave the little trunk where it is,—only take out the money.”

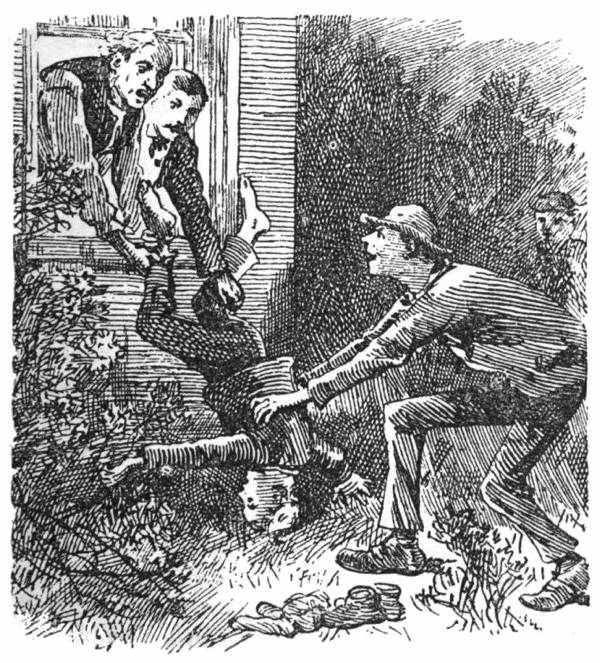

He had gone into the log for the last time, and got the last of the money, filling both shoes quite full, and was bringing them out with him,—he had actually got them out, leaving one at the entrance to the opening, and holding the other in his hands,—when Lion, notwithstanding his previous punishment, uttered a very low, suppressed growl.

Jack looked up from under his tumbled hair, and there, not three yards distant, with his horn-headed cane, regarding with grim amazement the boy and his shoes full of coin, stood Squire Peternot!

Fearing a raid upon his melon-patch, which bad boys in the neighborhood were beginning to molest, the squire had stayed at home to watch it that Sunday afternoon. He had seen Jack with his dog and basket cross the fields, go to Aunt Patsy’s house, and afterwards enter the woods; and, feeling the interest of a stern moral censor in the conduct of all Sabbath-breaking boys, he had followed him to the hollow log. Lion’s indiscreet barking had at first served to guide him to the spot; and afterwards his equally unfortunate silence, in consequence of the punishment he had suffered for that offence, favored the old man’s stealthy approach.

To have the faintest idea of the emotions that agitated the squire at sight of Jack and the shoes full of coin,—the wrath, the surprise, the avarice,—one must have seen him as he stood there, or have heard Jack (as I have heard him many times) describe the grim and frowning figure that met his eyes.

“What’s this, what’s this, eh?” cried Peternot, taking a stride forwards. “Money! on my land!” and the gray eyes glittered. “Ha! ha! This, then, is the meaning of all that talk about treasure-trove the other day!”

Jack felt so stunned for the moment that he did not attempt to speak, or even to rise. He sat on the ground, guarding his shoes, keeping one hand on the rim of the basket and looking up steadily at the squire with eyes full of mingled fear and defiance.

“So, so! What have you got in your basket?” And the stiff-jointed old man stooped to remove the coat which Jack had taken the precaution to spread over it each time when he entered the log.

“Here! you just leave that alone!” exclaimed Jack, while Lion gave a fierce growl. The squire dropped the garment instantly, but he had pulled it far enough from the basket to expose its surprising contents.

“Boy!” said he, in still greater amazement, “are you a robber?”

“Like enough I am,” muttered Jack, quite willing that he should take that view of the case.

“Boy!” repeated Peternot, with awful severity, “you’ve stolen this money, and it’s my duty to have you arrested. I am a justice of the peace.” Jack changed countenance at that.

“I’ve stolen it about as much as I stole Mr. Chatford’s horse and buggy once, which you were so sure of, when they were all the while standing under the shed at the Basin, just where Mr. Chatford left them.”

“Then how did you come by so much money?”

“If you must know, I found it in this log,” said Jack, with a sudden determination to tell the plain truth, and stand or fall by it.

“How do I know but what you stole it and hid it here, so you could pretend you’d found it?”

Jack was glad now that he had not removed the trunk.

“If you can’t see by the look of this silver that it’s been hid away here longer than I’ve been in the town,” he replied, “you can just go into the log and find the trunk, that you’ll say has been there about as many years as I am old, that’s all!”

“Is there any more money in there?”

Jack was willing the squire should think there might be, nor was he sure there were not a few pieces in the rubbish about the trunk; so he said, “It belongs to me, if there is.”

“Belongs to you? You little scapegrace! By what right?”

“It belongs to me,—that is,” added Jack, “if the real owner doesn’t turn up,—because I found it.”

“Found it, on my land! You haven’t got it off from my land yet, and I forbid your taking it off. What’s left in the log you haven’t even had in your possession. I want nothing but what’s my own by a plain interpretation of law; but the law’s with me in this. If you had once fairly got the coin away without my knowledge, there might have been some question about it; but that you’ve been caught trespassing, and that you’ve no right to take anything from my premises in my presence and against my express orders, is common sense as well as common law.”

Fire and tears rushed into poor Jack’s eyes.

“And do you mean to say you’ll take all this money away from me?”

“Sartin, I do, since it don’t belong to you, not a dollar on ’t. I’ll make ye a reasonable reward, however, if you give it up without making me any unnecessary trouble.”

“What do you call a reasonable reward? Half?”

“Half! of all that money!” exclaimed the squire, in huge astonishment. “Preposterous! I’ll give ye more than liberal pay for your trouble. I’ll give ye five dollars.”

Thereupon grief and fury and fierce contempt burst from the soul of Jack. All the softening influences which had been at work upon him for the past few months were forgotten in a moment; he was the vicious, desperate, profane little canal-driver once more. Looking up through tears of rage at the startled squire, he shouted, “Go to thunder, you hoary old villain!” and followed up this charge with a volley of blasphemy and abuse, which lasted for at least a minute. By that time the squire had recovered his self-possession; so, in a measure, had Jack; and the hurricane of passion that had swept everything before it was followed by a lull of sullen hate and despair.

“That’s the kind of boy you are, is it? after all your living among Christian people!” said the old man, with a sort of grim satisfaction.

“It’s the kind of boy I was, and it’s the kind of boy such Christians as you are will make me again, if I let you!” said Jack, kindling once more. “I didn’t mean to swear, but I forgot myself. I haven’t before, since the first Sunday after I came off from the canal. That’s because I have been living among Christians,—people who try to encourage a fellow and help him, by bringing out the good that’s in him, instead of grinding him down, and keeping him down, by telling him how bad he’s always been and always will be,—like the kind of Christian you are!”

“Talk to me about being a Christian, you profane Sabbath-breaker!” said Peternot, choking with indignation.

“A Sabbath-breaker, am I? And what are you? I own up to what brought me here to-day, but what brought you here? What keeps you here? Why ain’t you at church? Guess you consider your worldly interests worth looking after a little, if ’tis Sunday,—don’t you?”

“Come, come, boy! that kind of talk won’t help matters.”

“Then le’s stop it,” said Jack. “But if you come here on Sunday and try to get my money away from me, and accuse me of Sabbath-breaking because I mean to keep it, I shall have just a word to say back, you better believe!” And, still sitting on the ground, Jack held his shoes between his legs, and guarded one side of the basket, while Lion guarded the other.

“What do you want of so much money,—a boy like you?” said the squire, adopting a more conciliatory tone.

“What do you want of it,—a man like you? without a child in the world, since you drove your only son away from home by your hard treatment, and he died a drunkard and a gambler!”

The old man fairly staggered backward at this cruel blow, and uttered a suppressed groan.

“It was mean in me to say that,” added Jack, relenting; “I didn’t mean to; but you drove me to it. What do you want of more money than you’ve got already?—that’s what I meant to ask. You’re a rich man now. You’ve ten times as much as you need; what do you want of more? To carry into the next world with ye? one would think so,—an old man like you!”

“Boy!” said the trembling Peternot, “you don’t know what you’re talking about!”

“Yes, I do; I’m talking just what a good many other folks talk, only not to your face. They say, ‘There’s old Squire Peternot, seventy years old, with one foot almost in the grave,—rich enough in all conscience,—don’t use even the interest on what money he has, but lays it up, lays it up,—lives meanly as the poorest farmer in town,—never gives a dollar, except when he can’t help it, and then you’d think it hurt him like pulling his teeth,—and yet there he is, trying to get Aunt Patsy’s little house and lot away from her,—making tight bargains, screwing his workmen’s wages down to the lowest notch’; that’s what I’ve heard, every word of it, and you know that every word of it is true!”

“I have my own ideas about property,” said the squire; “and no man—no prudent man—likes to squander what’s his own.”

“And so you, with all your wealth, come and grab this money, which is all I have in the world, and offer me five dollars to give it up to you! You are a prudent man! I say squander!”

“I’ll give you twenty dollars of it,—and that’s liberal, I’m sure,” said Peternot, a good deal shaken by what Jack had said, but unable, from long habit, to take his hand from any worldly goods that it chanced to cover.

“Twenty dollars!” laughed Jack, with scornful defiance. “I don’t make bargains on Sunday.”

This cool sarcasm caused the worthy Peternot to wince as at the taste of some bitter medicine. “I don’t bargain on the Lord’s day, neither. But I see the necessity of coming to some sort of terms with you.”

“Very well; then you just walk off and leave me and my dog to take care of this money; those are the only terms you can come to with me.”

“But what do you propose to do, if I don’t walk off?”

“Stay here,—Lion and I,—and hang on to our treasure-trove. Your nephew, who knows so much about law, advised me to keep possession,—to fight for it,—and I will.”

“And do you think I’m going to give up to you, you renegade?” cried the squire. He moved to lay his hand on the basket; but there was something in Lion’s growl he didn’t like. “I’ll beat that beast’s brains out, if he offers to touch me!” he exclaimed, grasping his cane menacingly.

“I advise you not to try that little thing,” said Jack. “If you should miss your stroke, where would you be the next minute?”

The squire thought of that. His tone changed slightly.

“I don’t leave this spot till I git possession of that money!”

“All right, Squire. Sit down,—you’d better. You’ll have some time to stop, I guess. Have a peach?” And the audacious little wretch took one out of his coat-pocket. “We shall need refreshments before we get through!” As Peternot indignantly declined the proffered fruit, Jack quietly broke it open, and ate, with a relish, the rich yellow pulp. The old man accepted the invitation to sit down, however, and reposed his stiff old limbs on the end of the hollow log, not clearly foreseeing how this little adventure was to end.

A little calm reflection opened the squire’s mind to a ray of light which would certainly have dawned upon it before, had not his wits been clouded by passion. “Boy!” he suddenly exclaimed, “I believe every dollar of that money is bogus.”

“Then what’s the use of making a row over it?” was the boy’s cool retort.

“It’s the business of a magistrate to look after counterfeiters and counterfeit money,” said Peternot. But at the same time he thought, “He has satisfied himself that it ain’t counterfeit; his whole conduct shows it.” And the avaricious old man still laid siege to the basket.

Half an hour passed, during which time very little was said. Jack took out his knife and began to whittle a stick; perhaps he was not unwilling to show the squire that he was armed. He also put on his coat, and then his shoes, after emptying their contents into the basket.

Peternot grew more and more impatient, as he saw the afternoon gliding away. Another half-hour, and the situation still remained unchanged. “I may set here till night,” thought he, “and all night, and all day to-morrow, fur’s I know,—but what’s the use? He’ll stick as long as I do. He’s tough; he can stand anything; ye can’t starve a canal-driver. Sakes!” he exclaimed, half aloud, suddenly putting his hand into his pocket, remembering that the key of his kitchen door was there.

On leaving home he had carefully made fast all the doors and windows of his house,—his wife and nephew having gone to meeting that afternoon; and now, should they return before he did, they would find themselves locked out!

Still the old man’s cupidity would not suffer him to raise the siege.

He was taken by a fit of coughing; and, fearing to catch cold by sitting on the damp log, he got up and walked about,—frowning and striking his cane upon the ground in huge dissatisfaction and disgust. “You’re the most obstinate, unreasonable boy I ever see!” he exclaimed angrily.

“Am I?” laughed Jack. “You haven’t begun to see how obstinate I am. Wonder what you’ll think to-morrow at this time? or the next day?” And what, he might have added, would the wife and nephew think?

“Hush!” whispered the old man. “What boys are those?”

There was a crackling of sticks in a not very distant part of the woods, occasioned by a gang of four or five boys climbing Peternot’s brush fence. Jack jumped upon the log and looked.

“It’s the Huswick tribe,” said he. “There’s Dock, there’s Hank, there’s Cub,—there they all are, going over your fence like a flock of sheep!”

“The Huswicks, Cub and Dock,—Hank with ’em!” ejaculated the squire, in great excitement. “They’re the wust set of boys in town!”

“Yes, and they’re putting straight towards your house,” observed Jack.

“They’re after my melons!” said Peternot, brandishing his cane. “The rogues! I’ll larn ’em!” With a limping stride he started in pursuit, but turned back immediately. “Promise me you’ll stay here!”

Jack couldn’t help laughing at the old man’s simplicity. “Do you think I’m such a fool as to make that promise? Or even if I should, would you trust me to keep it? Come!” cried Jack, “you must have a better opinion of me than you pretend.”

“I know you have some good traits—the rogues will destroy all my melons—if I could borrow your dog—leave your basket and go with me—we’ll settle our diffikilty when we come back,” said the agitated squire.

“I’ll take care of my basket; you can look after your melons,” retorted Jack.

“I’d as lives have a passel o’ pigs in my melon-patch!” cried Peternot, striding to and fro. “Boy! I’m sure this money is bogus!—I wish I had called to ’em ’fore they got out o’ hearin’!”

“Why didn’t ye?” asked Jack.

“That might ’a’ led ’em to come here, and we don’t want anybody by the name o’ Huswick to have a hand in this business. But my melons!—Boy, be reasonable!”

“Be reasonable yourself, Squire Peternot! You’re sure this money is bogus; then why don’t you leave it and go for your melons?”

“I ain’t sure,” replied the squire. “But you’re sure it’s good money; I see that, and you’re no fool.”

“Thank ye, sir,” said Jack, politely. And, seeing that the old man’s cupidity made him ready to believe almost anything, he added, “Now look here! If I’ll give you what money there is in the basket, will you be satisfied?”

Peternot started. “Satisfied? Sartin—I can’t tell—explain!”

“Will you take this, and leave me what there is still in the log? That’s what I mean,” said Jack, with an air of candor.

Peternot, astonished by this strange proposition, but afraid of being cheated out of a few dollars, asked, “How much is there in the log?” at the same time stooping with difficulty and peeping into the cavity.

“That’s my risk. Come, is it a bargain?”

“I thought you didn’t make bargains on the Sabbath day!”

“Well, I don’t,” laughed Jack, “unless some good man sets me the example. I’m only a boy,—it’s easy to corrupt me.”

“Corrupt you! you sassy, profane—”

“Sabbath-breaker,” suggested Jack, as Peternot hesitated for a word bad enough. “What do you say to my offer?”

“I say, if there’s money in the log, it belongs to me, the same as this belongs to me.” And the squire, impressed by the importance of having some accurate knowledge on that point, vigorously thrust in his cane.

“Your stick can’t give ye much information,” said Jack. “You’ll have to go in yourself.”

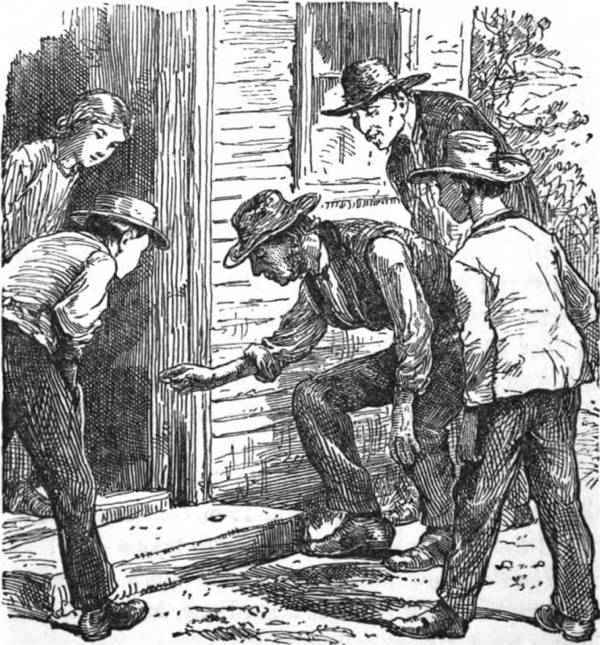

“I’m going in myself!” exclaimed the squire, sharply. “Move out of my way here.”

Jack readily made room for him, tickled to the heart’s core at the thought of the stiff-jointed old man’s going into the log.

“Grin, will ye?” said Peternot. “I s’pose you think the minute I’m in there you’ll start to run with your basket. But you can’t run fur with that weight to carry; I shall ketch ye!”

He leaned his cane by the log, laid his hat beside it, and put his head and one arm into the cavity. Then he put in his shoulders and both arms. “I can hear ye, if ye stir to move!” he cried from the hollow depths, which muffled his voice; and in his body went, leaving only the long Peternot legs sticking out.

Jack was convulsed with laughter. But all at once the idea occurred to him that practical advantage might be taken of the squire’s ludicrous situation. Up he jumped, and seizing the largest of the sticks with which he had previously stopped the mouth of the log, began to thrust them in after the squire.

“Here! oh! oh! murder!” cried the voice, now more muffled than ever, while the old man struggled violently to get out. “Oh! oh!”

“Good by!” screamed Jack, holding him, and thrusting in more sticks. “You may have what’s in the log, and I’ll take the basket.”

PETERNOT IN THE HOLLOW LOG.

“Help! ho! I’m killed!” said the voice, growing fainter and fainter.

“And buried!” Jack yelled back, laughing with wild excitement. “But you kick well, for all that!” And in went more rubbish about the old man’s heels. “How do ye like your bargain? You’ll have plenty of time to count your dollars before I send Pipkin over to help you out.”

And, having got the old man wedged so tightly into the log that he could not even kick, Jack, inspired with extraordinary strength for the occasion, caught up his basket of coin and started to run, followed by Lion.

Running quickly behind walls and fences, the Huswick boys made a rapid raid upon Peternot’s melon-patch, and left it loaded with spoils.

“Say, Dock!” said Hank (nickname for Henry), skulking behind some bushes, “le’s put for Chatford’s orchard, and scatter rines by the way, so if we’re tracked the old man’ll think ’t was the deacon’s boys hooked his melons.”

“Go ahead!” said Dock (nickname for Jehoshaphat), carrying two fine ripe melons on his left arm while he dug into one of them with a jack-knife in his right hand. “Stoop, and keep clus to the fence!”

“No danger, old man’s gone to meetin’,” said Cub, whose real name was Richard,—his odd shape (he was ludicrously short and fat) having probably suggested the nickname.

“Me an’ Cub can go without stoopin’,” giggled Hod, the youngest (christened Horace). “See Hank! he looks like a well-sweep!”

And indeed the second of the boys, who was as wonderfully tall and lank as Cub was short and thick, bore no slight resemblance to that ornament of country door-yards.

“Hanged if one o’ mine ain’t a green one!” exclaimed Tug (short for Dwight), dashing to the ground a large watermelon, the sight of which in ruins would have made old Peternot’s heart ache.

“Guess we made a clean sweep of all the ripe ones,” said Cub. “No, you don’t!” as Tug offered to relieve him of one of his three. “I never had my fill o’ melons yit, though I’ve”—cramming his mouth while he continued to talk—“been in the squire’s patch much as once afore now.”

“You never had your fill of anything, I believe, Cub!” said Hod, with his usual giggle. “Remember when we went there in the night last year?”

“Night’s no time to go for melons,” said Cub. “Ye can’t tell a ripe one ’thout cuttin’ into ’t.”

“Yes, ye can,” said Tug; “smell on ’t. That’s the best way to tell a mushmelon.”

“Cub’s terrible petic’lar about slashin’ the ol’ man’s whoppers, all to once,” said Horace.

“Of course, for if we cut a green one we sha’n’t find it ripe next time we go,” Cub explained. “Jest look! we’re makin’ a string o’ rines all the way from Peternot’s to the deacon’s orchard!”

“There now, boys,” said Hank, “throw what rines ye got down here by the brook, an’ stop eatin’ till we git to the woods.”

Their course had been westward, until they reached the orchard. They now took the line of stone-wall which divided the squire’s land from the deacon’s, and which led northward to the corner of Peternot’s wood-lot,—Hank following Dock, Cub following Hank, Tug after Cub, and Hod bringing up the rear. In this order they entered the woods, and were hastening to find a secluded spot where they could sit and enjoy their melons, when suddenly Dock stopped.

“Thought I heard somebody,” he said to Hank, coming up.

“So did I. Lay low, boys! Git behind this log!”

Down went boys and melons in a heap, each of the brothers, as he arrived, tumbling himself and his load with the rest. There they lay, only Hank’s long, crane-like neck being stretched up over the log to reconnoitre; but presently even he thought it time to duck, and threw himself flat upon the ground with the rest.

“Keep dark!” he whispered; “it’s that Jack Hazard, that lives to the deacon’s! him an’ his big dog!”

Jack indeed it was, who had been too intently occupied in fastening Peternot into the log to notice the approach of the Huswick boys. He had thought of them, to be sure, but had supposed they would return through the woods as they went.

He was now running as fast as he could with his basket of treasure, directing his course towards the orchard, but keeping a little to the right in order to reach a low length of fence, over which he intended to climb, and then betake himself to the smoother ground of the pasture. A log lay in his way. Lion, growling, drew back from it—too late. Jack, in his headlong haste, sprang upon it, and leaped down on the other side, alighting on a frightful heap of legs and heads and watermelons. He jumped on Hank, tripped against Cub, and, falling, spilt his basket of rattling coin all over Tug and Dock and Hod. Thereupon the heap rose up as one man, astonishing poor Jack much as if he had stumbled upon a band of Indians lying in ambush.

“What in thunder!—Jerushy mighty!—half-dollars!” ejaculated Cub and Dock and Tug; while Hank stretched himself up to his full height, and Hod fell vindictively upon Jack.

“Le’ me go!” screamed Jack, taking his knee out of a muskmelon, and shaking off his assailant.

“That’s my melon,” said Hod, diving at him again furiously, “an’ you’ve smashed it!”

He was butting and striking with blind rage, when Lion bounced upon him, and actually had him by the collar of his coat, dragging and shaking him with terrible growls, when Tug and Cub and Dock—one catching Hod by the heels, one Jack, and the other Lion—disentangled the combatants.

“Where j’e git all this money?” demanded Cub.

“Found it, and I’m carrying it home,” said Jack, scrambling to pick up his scattered half-dollars.

“He’s murdered somebody for it!” cried Hank, peering in the direction of the hollow log. “I heerd him! Hold on to him, boys!” and he ran to make discoveries.

“Don’t ye do that!” said Jack, as Hod rushed to help him pick up the coin. “My dog will have hold of ye again! Watch, Lion!”

“Take that out o’ yer pocket, Hod!” said Cub, seizing his youngest brother by the neck. “Melons is fair game, but now ye’re stealin’. None o’ that while I’m around!”

Hank, meanwhile, had reached the hollow log, beside which the hat and cane were; when, hearing groans from within and seeing a pair of legs sticking out, he began at once to remove the rubbish from the opening. Dock and Tug went to his assistance; and, each laying hold of a leg while Hank pulled energetically at the coat-tail, poor old Peternot, half smothered, fearfully rumpled, and frightfully cross, was hauled out by the heels horizontally.

When at length the squire stood upon the legs he had been drawn out by, and found himself in the presence of the Huswick boys, the recognition and pleasure were mutual.

“You scoundrels!” he began, brushing the dirt from his clothes and hair.

“What are we scoundrels fer?” said Hank, the tall one, with a comical grin on his thin, sinewy features. “Fer snakin’ ye out of the log?”

“If ye ain’t satisfied, we can pack ye in agin,” suggested Dock. But Peternot did not seem to take that view of the matter.

“How come ye in there, anyhow?” said Tug. “Was he murderin’ on ye?”

“Yes! Where is the villain? He’s got my money!” And away limped the old man in pursuit of the youthful robber and assassin.

“Them melons!” whispered Tug.

“Can’t help it now,” muttered Dock. “Hank, I wish you’d left the old fox in his hole!”

Guided by the sound of voices, and the sight of a head or two between the standing trunks, Peternot marched straight to the log behind which Jack was busy picking up his half-dollars. There were Cub and Hod watching him, while Lion watched them; there also were the stolen melons,—an interesting sight to the angry squire.

“Hullo, boys!” said Hank, leaning over the log, with one foot upon it, “where did them melons come from?”

“Do’no’,” replied Cub. “They was here when we come,—wa’n’t they, Hod?”

“Them melons come from my garden, and they come by your hands!” exclaimed Peternot. “I know it! and I’ll have ye up for trespassin’, the hull coboodle of ye!”

“Look here, squire!” said Hank, “seems to me you’re a little mite hasty. You ought to know your friends better ’n all that. Where’d you be now, if ’twa’n’t for us? In that ’ere hole. And where’ll ye be agin in less’n no time, if ye ain’t plaguy careful? In that ’ere hole!”

“He says you was murderin’ on him, Jack,” observed Tug.

“That’s a likely story!” cried the excited Jack, who by this time had got his half-dollars all back into the basket again. “Could I put him into the log? He was in the log,—he was robbing me,—so I fastened him in and got away,—or I should have got away, if I hadn’t stumbled over you fellows. Now just help me home with this money, and I’ll pay you well.”

“Help him at your peril!” said Peternot. Then, seeing the importance of securing such powerful allies, he added, “Maybe I was hasty, boys. Help me home with my money, and I’ll say nothin’ about the melons.”

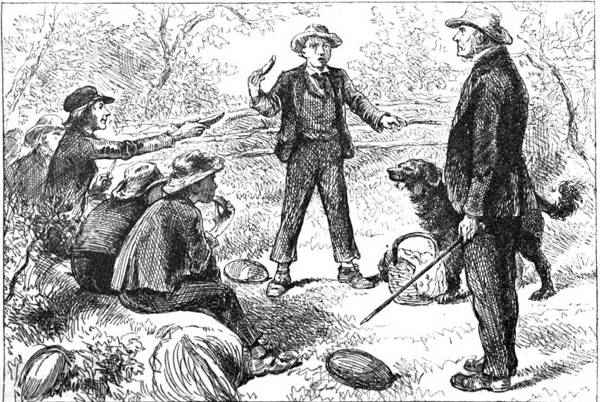

“That’s fair, if it’s your money,” said Hank. “Seems to be a dispute about it. Guess we’ll try the case. Come, now,—you fust, squire,—give in yer evidence whilst the court refreshes himself with a melon or two.”