GIACOMO

PUCCINI

BY WAKELING DRY

LONDON: JOHN LANE, THE BODLEY HEAD

NEW YORK: JOHN LANE COMPANY. MCMVI

Transcriber's note: On some devices, clicking a blue-bordered image will display a larger version of it.

BY WAKELING DRY

LONDON: JOHN LANE, THE BODLEY HEAD

NEW YORK: JOHN LANE COMPANY. MCMVI

Printed by Ballantyne & Co., Limited

Tavistock Street, London

LIVING MASTERS OF MUSIC

EDITED BY ROSA NEWMARCH

GIACOMO PUCCINI

| To face page | |

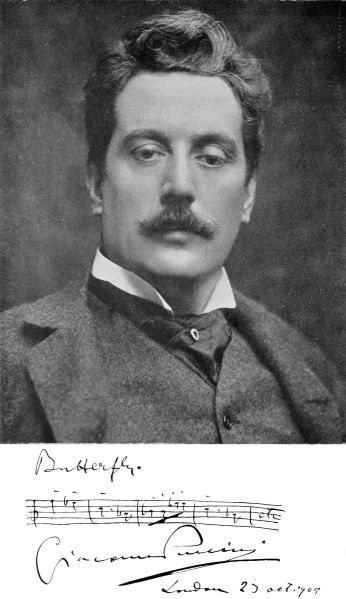

| GIACOMO PUCCINI | Frontispiece |

| From an autographed copy of a photograph by Bertieri, Turin, in the possession of the author | |

| PUCCINI'S BIRTHPLACE IN THE VIA DEL POGGIO, LUCCA | 8 |

| From a photograph lent by Messrs. Ricordi | |

| CHURCH OF ST. PIETRO, SOMALDI WHERE PUCCINI WAS ORGANIST | 12 |

| From a photograph lent by Messrs. Ricordi | |

| PUCCINI AND FONTANA, THE LIBRETTIST AT THE TIME | 18 |

| From a photograph lent by Messrs. Ricordi | |

| PUCCINI'S VILLA AT TORRE DEL LAGO | 22 |

| From a photograph lent by Messrs. Ricordi | |

| PUCCINI IN HIS 24-H.P. "LA BUIRE" MOTOR-CAR | 24 |

| From a photograph by R. de Guili & Co., Lucca | |

| PUCCINI AFTER A "SHOOT" | 28 |

| From a photograph by S. Ernesto Arboco | |

| PUCCINI IN HIS STUDY AT TORRE DEL LAGO | 40 |

| From a photograph lent by Messrs. Ricordi | |

| PUCCINI IN HIS MILAN HOUSE | 48 |

| From a photograph specially taken by Adolfo Ermini, Milan | |

| PUCCINI MANUSCRIPT SCORE. FROM THE SECOND ACT OF "TOSCA" | 50viii |

| From a photograph lent by Messrs. Ricordi | |

| MISS ALICE ESTY AS MIMI IN "LA BOHÈME" | 68 |

| From a photograph lent by Madame Alice Esty | |

| PUCCINI MANUSCRIPT SCORES. FROM THE LAST ACT OF "LA BOHÈME" | 72 |

| From a photograph lent by Messrs. Ricordi | |

| *PUCCINI IN "MORNING DRESS" (NATIONAL PEASANT COSTUME) AT TORRE DEL LAGO | 82 |

| *PUCCINI SHOOTING ON THE LAKE AT TORRE DEL LAGO | 82 |

| *PUCCINI SNOWBALLING IN SICILY | 86 |

| *PUCCINI WRESTLING AT POMPEII | 86 |

| *PUCCINI DESCENDING ETNA ON A MULE | 90 |

| *PUCCINI ON HIS FARM AT CHIATRI | 90 |

| PUCCINI AT TORRE DEL LAGO IN HIS MOTOR-BOAT "BUTTERFLY" | 96 |

| From a photograph lent by Messrs. Ricordi | |

| PUCCINI'S MANUSCRIPT. FIRST SKETCH FOR THE END OF THE FIRST ACT OF "MADAMA BUTTERFLY" | 102 |

| From a photograph lent by Messrs. Ricordi | |

| PUCCINI'S MANUSCRIPT SCORES. FROM THE FIRST ACT OF "MADAMA BUTTERFLY" | 112 |

| From a photograph lent by Messrs. Ricordi | |

| *From a series of snapshots given to the author by Signor Puccini (Copyright reserved) | |

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | PUCCINI, AND THE OPERA IN GENERAL | 1 |

| II. | PUCCINI'S EARLY LIFE | 9 |

| III. | THE PUCCINI OF YESTERDAY AND TO-DAY | 19 |

| IV. | "LE VILLI" | 30 |

| V. | "EDGAR" | 40 |

| VI. | "MANON" | 50 |

| VII. | "LA BOHÈME" | 68 |

| VIII. | "TOSCA" | 83 |

| IX. | "MADAMA BUTTERFLY" | 101 |

A big broad man, with a frank open countenance, dark kindly eyes of a lazy lustrous depth, and a shy retiring manner. Such is Giacomo Puccini, who is operatically the man of the moment.

It was behind the scenes during the autumn season of opera at Covent Garden in 1905 that I had the privilege of first meeting and talking with him, and about the last thing I could extract from him was anything about his music. While his reserve comes off like a mask when he is left to follow his own bent in conversation, one can readily understand why he adheres, and always has done, to his rule of never conducting his own works.

One thing struck me as peculiarly characteristic about his nature and personality. The success of Madama Butterfly—for that was the work in progress on the stage as we passed out by way of the "wings" to the front of the house—was at the moment the talk of the town. Puccini was full, not of the success of his opera, but of the achievements of the artists who were interpreting it. "Isn't Madame2 So-and-so fine?" "Doesn't Signor So-and-so conduct admirably?" "Isn't it beautifully put on?" The composer was content and happy to sink into the background and think, in the triumph, of all he owed to those who were carrying out his ideas. He has a quiet sense of fun, too. "Let us step quietly," he said—as we came into the range of the scene that was being enacted—"like butterflies."

I have called Puccini the operatic man of the moment. It is not difficult to account for his popularity. His whole-souled devotion to this one form of musical art, in which he has certainly achieved much, has by some been pointed to as defining his limits. Apart from a few early string quartets, which mean nothing more than the usual preliminary studies of a gifted student, Puccini has written absolutely nothing but operas since he started. In this respect his music has a certain well-defined natural characteristic that gives him—if it be necessary in these days to fit any particular composer into his own special niche—a distinct place in the history of the progress and development of the art and science of music making.

Roughly speaking, the opera had its beginnings in the dance, but almost at the same time it travelled along the road of the development of vocal expression by music. As early as the days of Peri and Caccini, who reverted to the old Greek drama as the basis on which to build something anew, and by so doing brought forth the germ which was afterwards to bear fruit through Gluck and Wagner, the feeling for freedom of expression, the desire to snatch music away3 from the tyranny of a set form—counterpoint, as it was then understood—strove to make itself felt and understood. It must not be taken to mean that the old contrapuntists did not endeavour to combine the adherence to a form with some degree of definite expression; for in the works of one of the greatest of this school, old Josquin des Près, are to be found plenty of emotional touches by which, even in so restricted a pattern as the madrigal form, it was plain that a closer union between words and music—an emotional feeling, in short—was clearly the thing striven for.

Still dealing briefly with beginnings, one may point to the dramatic cantatas—particularly in Italy, but found in France as well—or madrigal plays, by which, in distinction to what may be called little comedies with music, this essential "operatic" feature in the union of the arts of speech and song, comes out with special clearness.

In Italy then, the land which owns Puccini as one of its most distinguished sons, the opera had its rise; and in Dafne, the first child of a new art, it is curious to note, it immediately turned aside into one of those many by-paths which led it very far away from the goal of its promise. Curious again is the reason for its first fall—the desire of the leading singer for vocal display, and the introduction of long vocal flourishes, which, having nothing to do with the case, yet pleased the public mightily. In this Dafne—the score of which has been lost—it was the great singer Archilei who was the offender. Yet again a strange thing4 comes down to us after these many years. Peri, the composer, was highly delighted with the interpolations and the vocal gymnastics.

But out of something dead, something very much alive was destined to develop. The old Greek drama was not to be resuscitated by a sort of transfusion of blood—music, the newest and most emotional of the arts, being the medium to carry life into the structure. There is not space here to do more than hint at the various fresh phases—the reforms, as they have been called—each of which, in trying to deal with what was already built up, really brought to an achievement the ideal which had floated before many a worker in the same field.

In Italy, as early as Cimarosa's day—he died in 1801—the opera, regarded purely as a musical form, attained as near perfection as possible. It is difficult, even when dealing with a period that, unlike our own, was very much more concerned about the manner than the matter of things, to distinguish between the various styles of opera; but taking the opera seria and the opera buffa as representing two great phases of the art, Cimarosa stands out as one who combined the essential qualities of both into products which had the stamp of individuality. Pergolesi is another shining light who stands out in the long line of illustrious workers whose efforts were entirely cast into the shade by the arrival of Rossini and his followers, Donizetti and Bellini. All this time, during which so-called Italian opera dominated the whole of Europe, nothing was done in Italy in the way of developing orchestral5 writing, which in Germany had made such marvellous strides. At the psychological moment—for Italy—came Verdi, who, if he took the opera very much as he found it, breathed from the very first a new spirit into its composition. His artistic growth, as seen by his later operas, was one of the most remarkable things in modern musical history. And in the fulness of time we come to Puccini, to whom it is reasonable to point as the successor of Verdi. These two, who may be linked up with reason with Boïto and Ponchielli, present many features of resemblance. Puccini's musical expression, at first purely vocal, has in his later work shown that same growth in artistic development. From the beginning he was concerned with the continuous flow of melody, since he had not, like Verdi, to get away exactly from the old form of the set numbers; but in Puccini's case, the growth referred to is seen in his latest work in the further elaboration of the orchestral portion. Although in England we have had few experiments worked out in the way of the development of opera, it is safe to say that such new modern works as have been taken to our hearts have owed not a little to the orchestral part of the fabric. Tchaikovsky's Eugen Oniegin and Humperdinck's Hänsel und Gretel are at least two notable cases in point.

But in whatever way we view an opera, mere orchestral fulness will not serve to land the work very high up in the esteem of music lovers. Nor will the purely beautiful in music—melody worked out with transparent clearness of form—save a poor, unconvincing or uninteresting dramatic fabric from passing6 into the great storehouse of the unacted. Puccini's music is dramatic, and by far the greater part of it, by a sort of quick natural instinct, is purely of the theatre. His first and most direct appeal is by the charm and vitality of the vocal expression, while his whole plan is one of movement. From the first—if we except for the moment his Le Villi, which was first called a ballet-opera—he called his operas Dramma per lyrica—lyric dramas, a term first established, and moulded into a definite art-form, by Wagner. With his first opera, Puccini started something of a new form in the short opera; and two remarkable works of the kind in Cavalleria Rusticana by Mascagni and I Pagliacci by Leoncavallo, which came very soon after, clearly indicate that he had founded a school as it were; and so from Italy to-day, as in times past, this particular fashion spread to other countries. Puccini, still exhibiting, with a strong and in many ways typical national feeling, spontaneous vocal melody as his leading characteristic, did not limit himself to the perfection of the short opera. His subsequent works were of larger calibre. He left the fanciful and imaginative and the old world legends, and turned to everyday life for his subjects. In general form—for one must revert to this not particularly lucid description when dealing with opera—Puccini must be placed among the shining lights who have chosen to deal with what may be called light opera. Opéra comique, as translated by our term "comic opera," means something so entirely different, that although "light opera" is but a poor expression, it is one that may perhaps be most readily "understanded of the people."

7 The term "light" is associated practically entirely with the music. The subjects of Puccini's operas are all of them tragic, but the expression of the theme, the working out along the already roughly defined paths, is not by the heavy, the big, or the strongly moving in music. One may point almost to Bizet, as shown in Carmen, as the special point from which Puccini started. Furthermore, Puccini stands almost unrivalled in his own particular way in giving us, by means of operatic music, something very near akin to the comedy of manners in drama. Much might with advantage be deduced from the success of Puccini in this country, and the same result applied to the question of our national opera; or, seeing that such a thing does not exist, to the crying need for some encouragement to be given to native composers. Puccini, it may be, has become the vogue simply because he is light and lyrical, not so much here in the dramatic, but in the musical sense. No one, it is safe to say, at this time of day desires to go back in any shape or form to the old "set-number" sort of piece. Such a reversion may fittingly form the ideal towards which a follower of Sullivan—who in his Yeomen of the Guard gave us unquestionably the best definite "light" opera of the last generation—may strive to bring to perfection. Puccini has by the general mould of his work made his place and found his following on the operatic stage, and it is surely by the vocal strength and vocal continuity of his work that this place of his has been achieved and maintained. It is easy, of course, to point to the simplicity of the achievement when one sees the fruit of the labour: but without urging any one8 to copy an accepted model, or to merely repeat what has been already designed, one may wonder why, with so many gifted melodists among contemporary British musicians, no one has given us definite light opera. It is a direction in which our composers have never moved. If a reason for Puccini's greatness—or popularity, if you will—is wanted, it may be found in this extremely clever use of the light lyrical style. And lest there be any misunderstanding, let it be said that hardly one of Puccini's songs or dramatic numbers can be pointed to as making this or that opera an accepted favourite. "Che gelida manina" from La Bohème is trotted out by not a few budding tenors, and it may be occasionally heard at a ballad concert, but even this is not sung one-tenth as many times as, say, the prologue to I Pagliacci, leaving out of the question the extreme popularity, as an instrumental piece, of the Intermezzo from Cavalleria. Puccini's melodies, if they do not actually fall to pieces away from their surroundings, at least very quickly lose their full significance, and not a little of their charm. And it is for this reason, therefore, that Puccini stands as the most definitely operatic composer of the moment. He has had great opportunities, it is true, but he has had great struggles. Like Wagner, he is concerned, and ever has been, with just one phase of art. To those that come after may be left the task of deciding as to his exact place in the roll of fame. By the oneness of his endeavour, by the sincerity of his expression, by the spontaneity of his vocal melody, does Puccini stand worthily among the living masters of music.

In Lucca in 1858, in a house in the Via Poggia, Giacomo Puccini was born. The family originally came from Celle, a typical mountain village on the right bank of the Serchio. From the earliest times the family was one devoted to the art of music, and while the world knows only of the musician who is the subject of this book, the achievements of his musical ancestors were of no mean order.

It will be sufficient to trace back the family to one of the same name, a Giacomo Puccini, who, born in 1712, studied with Caretti at Bologna. During his student days he was the friend of Martini, and thus from very early days the Puccini family have had intimate connection with those musicians whose names will live as long as musical history. On returning to Lucca this Puccini was appointed organist of the cathedral and subsequently maestro di capella. His compositions were entirely in the domain of ecclesiastical music, and include a motet, a Te Deum, and some services.

His son, Antonio, also proceeded to Bologna for his musical training, and in process of time succeeded to10 the post at Lucca. Antonio's chief composition was a Requiem Mass, which was sung at Lucca on the occasion of the funeral of Joseph II. of Tuscany.

The first of the family to turn his attention to opera was Domenico Puccini, the son of the foregoing, who, like his father and grandfather, after studying at Bologna, and under the famous Paisiello at Naples, also held the post at Lucca. Of his several operas, Quinto Fabio, Il Ciarlatano, and La Moglie Capricciosa had a certain vogue in his day, but have passed into oblivion. Dying at the age of forty-four, he left four children, of whom Michele was the father of the Puccini with whom we are dealing.

The grandfather Antonio helped this young Michele and sent him to study at Bologna, where he came under the influence of Stanislaus Mattei, the teacher of Rossini. Later on he proceeded to Naples, where he was taught by Mercadente and Donizetti. Returning to Lucca he married Albina Magi, and was appointed Inspector of the then newly formed Institute of Music. Some masses and an opera, Marco Foscarini, stand to his credit, but it was as a teacher that this Puccini did his best work. Among his pupils were Carlo Angeloni and Vianesi, who afterwards won distinction as a conductor, not only in Italy but at Paris and Marseilles.

Michele Puccini died at the age of fifty-one in 1864, leaving his wife, who was then thirty-three, to provide and care for his seven children. It is interesting to record that the famous Pacini, the composer of Saffo, which is still regarded as perhaps the chief classic of11 the purely Italian school, conducted the Requiem sung at his funeral.

Puccini's mother and her noble work in bringing up her large family—for she was left with no great share of this world's goods—deserves infinitely more than this bare mention of her excellence. In the present instance, it is her patient care in making her fifth child, our Giacomo Puccini, a musician, that we have to recognise. But for this patience, the way of the man who was destined to achieve his own place in the annals of fame must have been still more rough. All praise then to the patient mother whose memory is still so lovingly cherished by her distinguished son.

Giacomo Puccini was only six when his father died, and as a child was remarkable for a restless nature and a keen desire to travel. He was sent to school at the seminary of S. Michele, and afterwards to San Martino. Arithmetic appears to have been his chief stumbling-block, but in everything, his curious irresponsible nature, his strong dislike to anything like guidance and restraint, made the acquisition of knowledge a hard task. Failing to acquire any sort of distinction in any branch of scholarship, an uncle of his, on his mother's side, tried to make him a singer; but the future musician, whose triumph was gained, curiously enough, in the display of the very art he despised, added, in this particular subject, one more to his many failures. The mother, in spite, doubtless, of a good deal of well-meant advice as to wasting time and money on a singularly unpromising youth, stuck to her conviction that Giacomo was destined by his12 gifts to carry on the long line of family musicians; and with many real sacrifices in the way of pinching and scraping, sent him to Lucca, where, at the Institute of Music, founded by Pacini, he came first under the influence of Angeloni, who, it will be remembered, was a pupil of his father. Infinite patience seems to have been the chief quality possessed by Angeloni, and by dint of great tact and sympathy, he infused an interest and something of a passion for music into his wayward young pupil. Giacomo became a fair player, and was sent off to take charge of the music at the church of Muligliano, a little village three miles from Lucca, and in a short time he had the church of S. Pietro at Somaldi added to his responsibilities. It was during the exercise of his church duties that the spirit of composition seems to have descended upon him, and certainly, if not in actually a novel way, a rather disconcerting one. During the offertory, and at other places in the Mass, it was the custom of the organist to improvise a more or less extended pièce d'occasion, a custom which still obtains. The officiating priests were more than occasionally startled by hearing, mixed up with these spirited improvisations of their young organist, certain plainly recognisable themes from operas, old and new.

There is no definite record of any specific continuation of studies while Puccini was contributing in a questionable way to the dignity of the church's service; but in 1877 there was an exhibition at Lucca, and a musical competition was announced, a setting of a cantata Juno, and young Puccini entered. As happened13 with Berlioz, so too the young composer's work was rejected, as not conforming in any way with the accepted canons of the art of music. Puccini at this point gave an early indication of that doggedness of purpose, a quiet pursuance of his own aims and working out his own ideas, which marked his later career, and which must have come as rather a surprise to his family, who regarded him in all probability as a lazy wayward youth. He did not take the refusal of the Lucca authorities to accept his work the least to heart, but arranged for a performance of it, and the public found it very much to their taste. About this time another early composition, a motet for the feast of San Paolina, was performed. With these successes, Lucca and its restricted area, with the evidently uncongenial work of a church organist, soon became entirely distasteful to him, and after hearing Verdi's Aïda at the theatre, his mind was made up. To Milan, the Mecca of the young Italian musician, he must go.

His mother still was his best friend; and although the cost of living and studying in Milan was sufficient to daunt the courage of any one far less hampered with domestic difficulties than she was, she bravely set about making the necessary sacrifices. Through a friend at Court, the Marchioness Viola-Marina, she enlisted the kindly sympathy of Queen Margherita, who generously agreed to be responsible for the expense of one of the necessary three years, while an uncle of hers came to her assistance by defraying the cost of the other two.

The Conservatory of Music at Milan is best known perhaps from the fact that the great teacher of singing,14 Lamperti, whose pupils number Albani and Sembrich, was a professor there up to the date of his retirement, in 1875. With the Royal College at Naples it represents at the present day the only survival of the most ancient teaching schools which began to be founded in Italy at the end of the fifteenth century, the name Conservatorio being given to the union of music schools for the preservation of the art and science of music. The oldest of them were the four schools at Naples, all of which were attached to monastical foundations, and which had their rise in the schools founded by the Fleming, Tinctor. There were four other schools, similar as to their foundation, at Venice, the origin of which was due to another great Fleming, Willaert.

On reaching Milan, Puccini's first thought was to bring himself earnestly to study, and to pass the necessary examination for entrance into this "Reale Conservatorio de Musica." Apart from his steady determination to mend his haphazard ways, it is good to note that his good resolutions were put to the test, for he does not appear to have succeeded at the first trial. But he had grit in him, and he stuck to his work bravely; and in 1880, towards the end of October, he passed his entrance examination with flying colours, coming out with top marks over all the competitors. His actual work as a student did not begin till December 16 of that year, and we get from an interesting letter to his mother a vivid picture of his doings at this time. Bazzini, the master with whom he was put to study, will be remembered as the composer15 of that favourite violin piece with virtuosi, the Witches' Dance.

"Dear Mamma,—On Thursday, at eleven o'clock, I had my second lesson from Bazzini, and I am getting on very well. To-morrow I start my theory lessons. My daily life is very simple. I get up at 8.30, and when I do not go to the school I stay indoors and play the pianoforte. For this I am trying now a new technical method by Angeloni, which is very simple.

"At 10.30 I have my lunch, and a short walk afterwards. At one I return home and study Bazzini's lesson for a couple of hours; after that from three to five I go to the piano again and play some classic. I have been playing through Boïto's Mefistofele, a kind friend having given me the vocal score. On! how I wish I had money enough to buy all the music I want to get!

"Five is dinner time, and it is a very frugal meal—soup, cheese, and half a litre of wine. As soon as it is over I go out for a walk and stroll up and down the Galleria. Now comes the end of the chapter—bed!"

All through the three years of his sojourn at Milan, Puccini, from the evidence of his letters which he sent home, seems to have preserved the simplicity of his nature, and to have kept in a remarkable way to his good resolutions. For composition he was put, shortly after his entrance, with Ponchielli, the composer of La Gioconda. For both his teachers Puccini had the liveliest admiration, and the following extract from another of his characteristic letters to his mother16 towards the end of his student days, showed how lively an interest Ponchielli took in his future:—

"To-morrow I have to go to Ponchielli. I have already seen him this morning, but we have had little opportunity of talking about what I am to do in the future, as his wife was with him. However, he promised to mention me to Ricordi, and he assures me that in my examinations I have made a favourable impression. I am now working hard at my exercise, towards the completion of which I have made good progress."

This exercise Puccini speaks of was the equivalent to the composition demanded by our Universities before a student passes to the degree of Bachelor of Music. With this Capriccio Sinfonica Puccini made his first mark as a rising composer. It was not apparently an entirely spontaneous outpouring, for he wrote it on all sorts of odd scraps of paper, just as the mood took him. It is curious to note that although in his general character he had made a radical change from waywardness to a steady determination and purposeful endeavour towards one definite goal, his methods of work and his music writing remained, to this day in fact, as very typical of the carelessness of the artistic temperament. His scores were, and still are, exceedingly difficult to decipher. Both Bazzini and Ponchielli were much attached to the promising young musician, but his handwriting—more particularly his way of setting down notes on paper—was more than once a great trial to their patience. Bazzini on one occasion inquired about this final exercise, and Ponchielli replied: "I really cannot tell you anything17 yet about it. Puccini brings me every lesson such a vile scrawl, that I confess, up to the present, I do no more than stare at it in despair."

When Ponchielli came to sit down and study the score of this Capriccio, the black-beetle-like splotches on the untidy manuscript did not prevent the worth of the music from coming through and making its appeal to the kindly teacher's mind. Both Bazzini and he were struck by its freedom, its freshness, its general grip of the orchestra. It was performed at one of the Conservatory concerts, and Puccini's fame, heralded by the critic Filippi, who wrote in a special article in the Perseveranza about the first performance, travelled round Milan. It is interesting to read what Filippi said about the first serious work by the future hope, operatically speaking, of young Italy:

"Puccini has decidedly a musical temperament, especially as a symphonist, having unity of style and personality of character. There are more of such qualities in this Capriccio than are found in most composers of to-day, thorough grasp of style, a quick sense of colour, an inventive genius. The ideas are bright, strong, effective. He is not concerned with uncertainties, but fills up his scheme with harmonic boldness, and knits the whole together logically and with perfect order."

This discerning writer goes on to speak of the skilful way in which the melodic material is worked up, and the general feeling for movement, states that it called forth the warmest enthusiasm, and dubs it by far the most promising work of that year.

18 Faccio, a well-known conductor, made arrangements to have it played at an orchestral concert, and Puccini wrote with joy and alacrity to his mother to arrange to have the parts copied, asking to have sent to him, without a moment's delay, twelve first violin parts, ten seconds, nine violas, eight cellos, and seven basses.

Flushed with his first real success Puccini was ready to act upon any suggestion that would enable him to keep the ball, once started, rolling along merrily. Ponchielli was struck with the essentially dramatic quality of Puccini's mind and bent, and promised to find him a suitable libretto so that he might start on an opera. He invited Puccini to spend a few days at his country villa at Caprino, and there Puccini met Fontana, who, like himself, was at the beginning of his career. After much cogitation, it was decided to collaborate in a short work, so that it might be ready for the Sozogno competition, the limit of time for that event having nearly expired. Thus it was that Fate, or Chance, settled the form in which, as it subsequently transpired, Puccini was from the very beginning to appear as a setter of fashion in opera. But, as we shall see, the path to fame did not immediately open to Puccini. The Sozogno prize was not won, but Le Villi, his first opera, was born, and, like Wagner, the ardent and now well-equipped young composer began to experience those pains and penalties, and bravely ploughed his way through thorns and over the rough places, and finally conquered by the sheer force of perseverance, endurance, and singleness of aim.

Puccini, after the death of his beloved mother, sought consolation in hard work, and Edgar was written in Milan during a period, which was in like manner experienced by Wagner, of additional anxiety, brought about by the want of the actual means to live. But it is undoubtedly that out of such trials and troubles the best work of the brain is forged and brought to an achievement.

Puccini was living at this time in a poor quarter of Milan with his brother and another student. With the £80 he received for Le Villi he paid away nearly half of it to the restaurant keeper who had allowed him credit.

Milan, the chief operatic centre of opera-loving Italy, is full of music schools, agencies, restaurants and cafés, whose reason for existence, practically, is found in the fact that half the population is in one way or another connected with the operatic stage. Milan is even more Bohemian than Paris in this respect, and it is not difficult to understand why the subject of unconventionality, as treated by Puccini in La Bohème, should have come to him20 with such force. He had, in fact, gone through the whole thing completely, so far as living on nothing and making all sorts of shifts for existence were concerned. Milan's social atmosphere is almost completely that of theatrical Bohemianism, and all the students come very intimately into contact with its essence and spirit.

There are many little stories of Puccini in his early days, which, after all, only represent the common lot of many a struggling genius the wide world over. He and his companions at the time Edgar was in the process of making rented one little top room in the Via Solferino, for which, according to Puccini's friend Eugenio Checchi, who has recorded the history of these early days, they paid twenty-four shillings a month. Puccini kept a diary, which he called "Bohemian Life," in 1881. It was little more than a register of expenses. Coffee, bread, tobacco and milk appear to be the chief entries, and there is an entire absence of anything more substantial in the way of food. In one place there was a herring put down; and on this being brought to Puccini's recollection, he laughingly said: "Oh, yes, I remember. That was a supper for four people."

As will be seen in the chapter on La Bohème, this incident was made use of by the librettists in the third act of that opera.

From the Congregation of Charity at Rome, Puccini was in receipt at this time of £4 per month. The sum used to come in a registered letter on a certain day, and he and his companions usually had to suffer the landlord to open it and deduct, first, his share for the21 rent. Many were the scenes they had with this worthy possessor of real estate. He had forbidden them to cook in the room, and even with the marvellously cheap restaurants, where at least the one national dish of spaghetti could be indulged in for the merest trifle, our group of young strugglers found it even cheaper to do their cooking at home. As the hour of a meal drew near, the landlord used to go into the next room, or prowl about the landing, to listen and to smell. The usual stratagem was to place the spirit lamp on the table and over it a dish in which to cook eggs. When the frizzling began, the others would call out to Puccini to play "like the very devil," and going over to the piano he would start on some wild strains which stopped when the modest omelette—two eggs between three—was ready to turn out.

The material for firing was another source of expense. Their modest order did not warrant the coal-merchant sending up five flights of stairs to deliver it in whatever receptacle took the place of the usual cellar: so Michael Puccini, the brother, used to dress up in his best clothes, including a valuable relic in the shape of a "pot-hat," and take with him a black-bag. The others said, "Good-bye, bon voyage," with some effusion on the door-step to let the neighbours imagine he was going away for a visit; and off Michael would go, to return in the dusk with the bag full of coal.

There is something infinitely pathetic in recording that Puccini, when fortune smiled upon him, wrote to this brother in great glee to tell him of the success of22 Manon, and to say that he was able to buy the house in Lucca where they were born. But Michael, who had departed to South America to mend his own fortunes, was then lying dead of yellow fever, to which he had succumbed after three days' illness.

Edgar being completed, the work brought him in about six times the amount he had obtained for Le Villi, while with Manon, which followed, his position became practically assured for the future. Always of a shy, retiring disposition, he had often longed to get away from the cramped conditions of town life, and Torre del Lago, on a secluded lake not far from Lucca, lying in beautiful country, surrounded by woods, and connected by canals with the sea—into which it flows just by the spot where Shelley's body was washed ashore and afterwards burned—was an ideal spot to which his thoughts had often turned. He went there to reside first in 1891, about the time he was writing La Bohème; but some time before that he had found a partner of his joys in Elvira Bonturi, who, like himself, came from Lucca, and whom he married. Their only son, Antonio, was born in the December of 1886. It was not until 1900 that Puccini built the delightful villa at Torre del Lago to which he is so devotedly attached, and to which he always refers as a Paradise.

Before finally deciding on a site at Torre del Lago—the Tower of the Lake—Puccini stayed for a time at Castellaccio, near Pescia, where a good deal of La Bohème was put to paper. Tosca was begun at Torre del Lago, and finished during a visit at the23 country house, Monsagrati, not far from Lucca, of his friend the Marquis Mansi. At the time of Madama Butterfly he was back at Torre del Lago, to which he was taken after his motor accident, but he was at this time the possessor of another country villa at Abetone, in the Tuscan Appenines, and in this latter place a good deal of his latest opera was set down. He has more recently built yet another country villa on the opposite side of the lake to Torre del Lago, on the Chiatri Hill. It is a charming example of the Florentine style of architecture, in which brick and marble are most skilfully blended. But Puccini told me, when last I saw him, that so far he had only spent a week-end in it.

Puccini, who was always addicted to sport and an open-air life, went in for motoring in the year 1901. His accident, by which he broke his leg and suffered a great deal of pain and anxiety owing to the difficulty of the uniting of the bone, took place in the February of 1903. He had left his beloved Torre del Lago and gone into Lucca for a change of air and place, owing to a bad cold and sore throat from which he could not get free. One of Puccini's characteristics is a certain obstinacy which very often leads him to do things in direct opposition to anything like a command. The fact that his doctor had told him not to go out in his car at night was sufficient, of course, for "Mr. James"—Puccini is invariably addressed by those round him as "Sor Giacomo"—to decide on a little evening trip; and he and his wife and son with the chauffeur started off in the country.

24 About five miles from Lucca there is a little place called Vignola, where is a sharp turn in the road by a bridge. Going at full speed, this was not noticed in the dark, and as the car turned, it went over an embankment and fell nearly thirty feet into a field. Mdme. Puccini and Antonio were unhurt, but the chauffeur had a fractured thigh and Puccini a fractured leg. Unfortunately, Puccini was pinned under the car, stunned and bruised by the fall; and, moreover, suffered considerably from the fumes of the petrol. A doctor, luckily, was staying at a cottage near by, and he was able to render first aid. Afterwards another doctor was sent for from Lucca, and it was decided to make a litter and carry Puccini to Torre del Lago by boat, as owing to the inflammation the leg was not able to be set immediately. Puccini's great friend, Marquis Ginori, went with him on the boat; and, although in great pain, the invalid found himself regretting that on the journey so many wild duck flew within range, just at the time, as he laughingly remarked, he could not shoot them. Three days after his arrival home, Colzi, a famous specialist from Florence, came and set the leg. The actual uniting of the bone was a long and tedious process, which spread over eight months, and Puccini was not really able to walk again properly until he had been to Paris—where his Tosca was produced at the Opera Comique—and undergone a special treatment at the hands of a French specialist. His first visit to Paris had been in 1898 for the rehearsals of La Bohème.

PUCCINI IN HIS 24-H.P. "LA BUIRE"

Photo. by R. de Guili & Co., Lucca

Puccini visited London for the first time when he25 came over for the production of Manon at Covent Garden in 1894. He came again in 1897 for the production in English of La Bohème at Manchester by the Carl Rosa Company. This was not, by all accounts, one of his most pleasant visits to a country of which he is very fond. Apart from the nervous worry of a first performance of a brand new work in a strange language, there were difficulties which made it a peculiarly trying time for the composer. Robert Cuningham, the Rodolfo, was unfortunately seized with a fearful cold which made him practically speechless on the night of the performance, and he could do no more than whisper his part. All things considered, it is not to be wondered at that Puccini, after spending nearly three weeks in rehearsal, decided to keep away from the theatre on the eventful night. He has himself written down his impressions of Manchester, as well as those of London and Paris.

"Manchester, land of the smoke, cold, fog, rain and—cotton!

"London has six million inhabitants, a movement which it is as impossible to describe as the language is to acquire. A city of splendid women, beautiful amusements, and altogether fascinating.

"In Paris, the gay city, there is less traffic than in London, but life there flies. My chief friends were Zola, Sardou and Daudet."

It was when Puccini was in Paris for the production of La Bohème that he first met Sardou and arranged about the setting of La Tosca. Sardou invited him to dinner, and after the coffee and cigars asked him to26 play a little of the music he thought of putting in the new opera. Sardou's knowledge of music, by the way, has, to say the least of it, its limitations, and Puccini is very loth to play anything he may have in his mind in the way of a composition. Puccini sat down at the piano, however, and played a good deal, which Sardou liked immensely. But Sardou did not know that the composer was merely stringing together all sorts of odd airs out of his previous operas.

Puccini's days at his beloved Torre del Lago are divided between sport and work. The beginning of his house, by the way, was a keeper's lodge, a mere hut, on the edge of the wood. It is so white that in the distance it looks like marble, but as a building it is quite unpretentious. There is a little garden leading down to the lake, while at the back stretches the fine open country. He is usually up and away early in the morning, accompanied by his two favourite dogs, "Lea" and "Scarpia." He goes to and fro from his shoots in his motor-boat "Butterfly." The place abounds with wild duck, wild swans and all sorts of water-fowl, the principal quarry from the sportsman's point of view being coots, hares, and wild boar. Puccini has been frequently snowed up while away shooting as late as April.

To the south of the lake, in the plain, are some remains of a bath attributed to Nero, with undoubted traces of a Roman road and a fosse. One can hardly move a yard in Italy without coming across villas of Lucullus, roads of Hannibal, or fields of Cataline, but this particular place, not only from the traces of buildings27 which remain, but from the result of excavation, by which many Roman remains were brought to light, is of great antiquity.

Coming in from a "shoot" Puccini often allows the best part of the day to pass in more or less what seems like idleness, preferring to put down his music at night—the one relic, one may say, of his old wayward restless ways. He works chiefly on the ground floor of his house at Torre del Lago, in a spacious apartment which is a sort of dining-room, study and music-room all in one. The ceiling is crossed with large wooden beams, and he calls the Venetian blinds, which are outside the many and large windows, "mutes" for the sun, using the word, of course, in its sense of a device for softening the tone of a musical instrument. The walls of the room are decorated with some quick impulsive designs, dashed on by his friend the artist Nomellini, representing the flight of the hours from dawn to night. For the rest, the room is full of photographs of all sorts of distinguished people, from Verdi downwards, and stuffed birds.

When the desire for work is upon Puccini, "it catches him," as an Italian would say, "by the scalp," and he works at a thing continuously. During the recovery from his motor accident he was wheeled to the piano each day and planned out Madama Butterfly, although the actual writing down of the melodies and the general work of construction was done, of course, away from the instrument. He makes a rough sketch of the whole score as a rule, which he subjects to all sorts of weird alterations only intelligible to himself,28 and from this makes a clean copy embodying all the process of polishing and finishing to which the original idea was subjected.

PUCCINI AFTER A "SHOOT"

Photo. by S. Ernesto Arboco

It is difficult to get from Puccini any particulars of his ideas and aims. He much prefers to do things rather than to talk about them. He has on one or two occasions, however, given a hint of his views which may be worth putting down again. One is on the interesting question as to dramatic instinct in music. Puccini maintains that it is a question not of instinct but experience. He says himself that his early works were lacking in dramatic quality, but he does not agree that if it is not inborn it cannot be developed. He maintains that the choice of librettos has more to do with it than anything else, and from the first he has worked a good deal in this way by more than the usual amount of consultation and exchange of ideas that goes on between a composer and the writer of the book. Marie Antoinette, at the time when I had the pleasure of talking with him, was the subject for an opera which was, at least, uppermost in his mind. "But I have thought of many subjects and stories," he said. "La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret and the Tartarin of Daudet are two well-known ones. The latter is pure fun, but I have always thought, when coming to the point, that I should be accused, if I set it, of copying Verdi's Falstaff. The former, I believe, Zola promised to Massenet. I have also thought of Trilby; and several excellent themes for plots could be gathered from the stories of the later Roman Emperors." One29 statement at least was very characteristic of Puccini. "My next plot must be one of sentiment to allow me to work in my own way. I am determined not to go beyond the place in art where I find myself at home."

Puccini is very fond of the theatre, and when last in London enjoyed the production of Oliver Twist—he is specially fond, in our literature, of Dickens—and The Tempest.

The Dal Verme Theatre, where Puccini's first opera was produced, has been the scene of many experiments in the art of opera. More than one composer has been able to get a hearing there, if no more, and among the list of trials and experiments—the value of which taken as a whole will doubtless some day be accounted at their proper worth, and which still come out like shades of the night to remind us how little we appreciate native endeavour—are to be found the names of more than one English composer. Among the notable successes which have been first launched at this theatre is Leoncavallo's I Pagliacci.

The cast and general production of Le Villi, as has been mentioned, was apparently more or less in the nature of a friendly "helping hand" held out to the unknown composer. The first performance was on May 31, 1884, and the cast as follows:

| Anna | Caponetti. |

| Roberto | D'Andrade. |

| Guglielmo Wulf | Pelz. |

When one thinks of modern extravagance, supposedly so necessary for the production of a new play or musical31 piece, it is little short of amazing to learn that the first performance of Le Villi cost a little over £20. Of course the main expenses were the costumes and the copying of the orchestral parts. Puccini's fellow-students, with that generous enthusiasm which is ever part of the artistic temperament, cheerfully swelled the ranks of the theatre orchestra, and Messrs. Ricordi printed the libretto for nothing.

Le Villi met with a favourable verdict, and Puccini's mother received the following telegram on the night of its production: "Theatre packed, immense success; anticipations exceeded; eighteen calls; finale of first act encored thrice."

The outcome of it all was that Messrs. Ricordi not only bought the opera, but commissioned Puccini to write another, thus beginning an association which has not only been marked by commercial success but by a very real and close friendship.

The following year it was given in a slightly revised version, divided into two acts, at the Scala, Milan, that Temple of Operatic Art which is the Mecca of every aspiring Italian musician. This performance took place on January 24, and was conducted by Faccio, the cast being Pantaleoni, Anton, and Menotti. It was not published by Ricordi until 1897, when it appeared with an English version of Fontana's libretto by Percy Pinkerton. In this year it was done at Manchester, at the Comedy Theatre, by Mr. Arthur Rousby's company, Mrs. Arthur Rousby being the Anna, Mr. Henry Beaumont the Roberto, and Mr. Frank Land the Wulf. Mr. Edgardo Levi conducted.

32 Fontana's story was a curious one to be dealt with by a Southern poet; for the basis of Le Villi is found in one of those curious Northern legends which seem to be the exclusive property of natures of far sterner mould. The Villis, or witch-dancers, are spirits of damsels who have been betrothed and whose lovers have proved false. Garbed in their bridal gowns, they rise from the earth at midnight and dance in a sort of frenzy, till the dawn puts an end to their weird revelry. Should they happen to meet one of their faithless lovers, they beguile him into their circle with fair promises; but, like the sirens of old mythology, they do so only to take their revenge; for once within their magic ring, the unrestful spirits whirl their victim round and round until his strength is exhausted, and then in fiendish exultation leave him to die in expiation of his broken vows.

The scene of Le Villi is laid in the Black Forest. An open clearing shows us the cottage of Wulf, behind which a pathway leads to some rocks above, half hidden by trees. A rustic bridge spans a defile, and the exterior of the cottage is decorated with spring flowers for the festival of betrothal. With this, his first opera, Puccini adopted the Wagnerian plan which he has since always adhered to, of a preludial introduction, indicative of the general atmosphere of the drama to follow, in place of the conventional overture. As the curtain rises, Wulf, Anna and Roberto are seated at a table outside the cottage, and the chorus hail the betrothed pair in a joyful measure. As the lovers move off to the back, the chorus tells something33 of the prospects of the two young people. Roberto is the heir of a wealthy lady in Mayence. He will have to visit her for the arrangement of the details of his inheritance, and will then return to wed the bride. The chorus then sings a characteristic waltz measure, whirling and turning and singing that the dance is the rival of love. It is a quick impulsive measure in A minor, and foreshadows in a clever way the weird dance which later on plays such an important part in the scheme. Guglielmo, the father, is asked to join in the dance, and he does so after a short instrumental passage leading back to the dance and chorus proper. Guglielmo dances off with his partner and the stage is clear.

Anna comes down alone as the orchestra finish off the rhythmic figure of the waltz. She holds a bunch of forget-me-nots in her hand, and sings of remembrance in a characteristic melody which at once reveals Puccini's individuality both in melody and structure. It varies considerably in the time, and has all that impulsive charm of movement with which Puccini always fits the situation and the sentiment. In actual structure the melody moves along in flowing vocal phrases, but they invariably drop on to an unexpected note and reveal thereby that piquancy of flavour which makes them singularly attractive. Anna is putting the bunch of flowers, the token of remembrance, in Roberto's valise when her lover comes in. Taking the little bunch he kisses it and puts it back, and then begs a token more fair—a smile. A characteristic duet then follows, in which Anna gives expression to the doubts34 she feels at her lover's enforced absence. A delightfully suave second section is sung by Roberto, in which he tells her of his love, strong and unending, born in the happy days of childhood. Anna catches the spirit of his fervent devotion, and the duet ends with their voices blending in a song of triumphant trust. The voices end together on a low note, but the orchestra carries the melody up to a high C by way of a climax, and then gives out a bell-like sound skilfully preceded by a chord of that somewhat abrupt modulation in which Puccini always delights, which portends the approach of night and the departure of Roberto. This bell-like note of warning comes in again during the short interlude which leads to the chorus, who return to sing of Roberto's departure ere the bright beams of sunset fade in the western sky.

Roberto bids Anna to be courageous, and asks her father's blessing. Slow and solemn chords usher in Guglielmo's touching prayer, in which after the opening phrases the lovers join their voices, repeating the sentiment of his pious utterances. Towards the end the full chorus is added to the trio; and this solidly written number, backed by a moving orchestral figure, ends impressively. Anna sings her sad farewell, the voice rising to a characteristic high A, and a short orchestral passage finishes the scene.

The second act is headed "Forsaken" in the score, and to the opening prelude is attached a short note explanatory of what has happened in the meanwhile. "In those days there was in Mayence a siren, who bewitched all who beheld her, old and young." Like35 the presiding spirit of the Venusberg who held Tannhäuser in thrall, so Roberto is attracted to her unholy orgies and Anna is forgotten. Worn out by grief and hopeless longing Anna dies, and in the opening chorus of the second act we learn that she lies on her bier, her features of marble paler than the moonlight. An expressive and solemn funeral march, the main theme of which is indicated by this preceding chorus, is then played by the orchestra, during which the funeral procession leaves Guglielmo's house and passes across the stage. In order to add to the air of mystery this is directed to be done behind a veil of gauze. At the end, a three-part chorus of female voices chants a phrase of the Requiescat. The tableaux curtains are dropped for a change of scene. The place is the same, but the time is winter, and the gaunt trees are snow laden. The night is clear and starry, and pulsing lights flash from the sides, adding their lurid and fitful brilliance to the calm cold light of the moon.

With a sharp detached full chord in G minor, the weird unearthly dance begins in quick duple time, the quaint rhythmic melody being composed of staccato triplets. Out of the darkness the figures of the witch-dancers appear and join in the dance as the frenzy increases. It is a highly characteristic movement, and one can hardly agree with the critic who on its first production, as will be seen hereafter, wished that it might be in the major key. For an uncanny, utterly restless and grim effect, most subtly presented by means of purely legitimate music, this number stands as an exceptionally fine example. The dance ends, and36 the witch-dancers are swallowed up in the darkness, while Guglielmo comes out to dwell on the villainy of Roberto and the cruel wrong done to his dead child. The prelude to his plaintive number is prefaced with a striking descending passage for the chorus. As he sings of the pure and gentle soul of his daughter, the legend of the witch-dancers comes into his mind, but at once he prays for forgiveness for such unworthy thoughts of vengeance.

From a passage for the hidden voices of the sopranos we expect the approach of Roberto. The recalcitrant lover is startled by the sounds he hears, but he thinks remorse, and not the Villis of the legend, is the cause of it. Into his mind there flashes the remembrance of all that has passed, and he goes towards the cottage-door with a pathetic hope that Anna may still be living. But he starts back as some irresistible force compels him to retreat. Again he thinks a wild fancy has deceived him, but once more the voices sound the note of approaching doom. "See the traitor is coming." He kneels in prayer, but at the end comes in the sinister phrase, "See the traitor is coming." He rises from his prayer to curse the evil influence that has wrought his destruction.

Then, at the back, on the bridge, appears the spirit of Anna. Amazed, Roberto exclaims, "She is living, not dead!" but Anna replies that she is not his love but revenge, and reminds him, by a repetition of her solo in the first act, when she sang to the bunch of forget-me-nots, of all his broken promises. Roberto joins in this strenuous and moving duet, and accepts37 with resignation the fate that has been too strong for him. Torn with the anguish of remorse he expresses his willingness to die. Anna holds out her arms, and Roberto seems hypnotised. Gradually the witch-dancers come on, and surrounding the pair dance once more in frenzy row carry them off. Over the characteristic dance is now placed a full chorus. The words "whirling, turning," which frequently occur as the movement gains in intensity, show the connection with the joyous measure in the first act. In this we find one of those effects of unity which, although slight enough in many cases, reveal the hand, if not exactly of a great master, of an original thinker and a particularly finished craftsman. Roberto, at the end of the main section of the chorus, ending on a long sustained top A, and then dropping sharply to the tonic (it is still as before in G minor), breaks away breathless and terrified and strives to enter the cottage; but the spirits drive him again into the arms of Anna, and once more he is drawn into the whirlpool. With a last despairing shriek, "Anna, save me!" he dies; and Anna, with an exultant cry of possession, vanishes, while the chorus change the words of their song to a shout of exultation.

By this first effort, slight in texture as it is, Puccini gave unmistakable evidence of that power of giving, by a series of detached scenes, an idea of impressionistic atmospheric quality which was afterwards so beautifully achieved in his La Bohème. From the criticism of Sala, who, as we saw in a preceding chapter, was present at the meeting at Ponchielli's38 house which led to the production of the opera, we get a sound idea of the general effect and trend of the music, which is worth quoting. It appeared in Italia of the day after the performance, at which, it may be mentioned, Boïto applauded vigorously from a box.

"It is, according to our judgment, a precious little gem, from beginning to end. The prelude, not meant to be important, is full of delicate instrumental passages, and contains the theme afterwards used in the first duet between the lovers. The chorus which follows is gay and festive and shows masterly handling of the parts: the waltz, which we should have preferred in a major key, is entrancing, one of the most characteristic numbers of the opera is the duet between Anna and Roberto. The prayer of benediction is another inspired page, in spite of its length. The polyphony of the vocal parts is masterly and the melodic flow most charming. The symphonic nature of the intermezzi which connect the scenes, more particularly the wild dance of the spirit forms, distinctly points to the arrival of a great composer."

While the salient points of the music appear to have been unerringly seized upon by the writer, the subtlety of the composer in making the first dance of the peasants foreshadow the furious revelry of the witch-dancers appears to have escaped the critic. But this desire for strongly marked effects is after all essentially typical of the race. In Italy, the clear, radiant sky, the pure air, the glorious strength of the light, does not permit of an appreciation for half-tones and the39 fascination of shadows. If all need not exactly be dazzlingly bright it must be quite distinct. Le Villi was a remarkable first opera, but it has not succeeded in keeping a place in the current repertory. The music is unquestionably dramatic, but the whole structure, words and music, has not that quality of characterisation which, together with the necessary dramatic force, makes up the theatrical effectiveness without which no opera can ever expect to hold the stage. To use a hackneyed phrase, Le Villi has the defects of its qualities, but from the freshness and individuality of its music there is no reason why it should not be given in our concert-rooms as a cantata. The dance movement, after all, would lose nothing by being given as an orchestral piece, and the spirit forms might well be left to the imagination. At any rate, Le Villi is, by a very long way, a far greater work than many a so-called "dramatic" cantata. These things take the place in our provincial towns of the opera abroad; and since we do not appear in the least likely to establish opera houses, it would be a good plan for the British composer to take Puccini's Le Villi as an example of what might be done with a cantata—an opera, after all, played without action or scenery.

With his second work for the stage, Edgar—the libretto being by Fontana, the author of the opera-ballet Le Villi—Puccini adopts the designation of lyric drama. Edgar is in three acts, and with it the composer attained to the dignity of a first performance at the Scala, Milan. It saw the light on April 21, 1889, with the following cast, the conductor being Faccio:

| Edgar | Gabrielesco. |

| Gualtiero | Marini. |

| Frank | Magini Coletti. |

| Fidelia | Aurelia Catareo. |

| Tigrana | Romeida Pantaleone. |

The vocal score was not published by Ricordi until 1905.

The theme of the drama is the familiar one of a man tempted by passion, who swerves from the "strait and narrow path," and who afterwards makes atonement. In the case of our hero, Edgar, the atonement comes too late, and the end, as in Carmen—which in general dramatic outline may be called the foremost if not the first operatic exploitation of the idea—is Tragedy.

41 In front of his book Fontana places a foreword to the effect that we are all Edgars, because fate brings to each of us love and death. He winds up with a moral statement, true if trite, that it is wrong to let ourselves be dragged away from pure love to mere sensual passion.

The action takes place in Flanders in the early fourteenth century. The scene of the first of the three acts shows us a square in a Flemish village, at the back of which is Edgar's house, and before it an almond tree. On the one side is the entrance to a church, on the other an inn.

Over the distant landscape dawn is breaking. With a bell effect, of which Puccini is so fond, the simple prelude begins. The plain and straightforward progression of light chords is French in character, but the bell effect is established musically by the simple leap of a fifth in the bass. The chords continue, with a filagree figure placed above them, and from delicate musical suggestion the effect turns to realism as the bell itself sounds, ushering in the notes of the unseen chorus, as the Angelus rings from the church.

Edgar is asleep on a bench before the inn, and peasants and shepherds cross the stage, greeting each other as they go to their daily toil. Fidelia, the daughter of Gualtiero, then comes on to the balcony and salutes the dawn in a characteristic melody which, although not based on the bell theme in the way of the use of a representative phrase, seems very naturally to grow out of the musical idea. She calls to Edgar and comes down, plucking a branch from the almond42 tree. Fidelia continues her address to Edgar in a melody which is much more broken in rhythm than her former one; and on her departure a curious chromatic passage, which seems to presage unrest and stress, leads to the entry of the chorus, who repeat, from afar but coming nearer, their greeting to the dawn, while Edgar turns to go after Fidelia.

Strongly dramatic and of distinctive colour is the orchestral passage which accompanies the entrance of Tigrana. She is a gipsy girl, who has been brought up by the villagers. She enters with a species of lute—or guitar, more properly perhaps—called the dembal, a stringed instrument in common use even now by descendants of the Magyar race. She laughs at Edgar with a fine scorn of his tame admiration for the gentle village damsel. "There! I have made Fidelia run away," she sings with a mixture of sarcasm, irony, and hypocrisy. "I am so sorry. I did not know a pastoral love affair was at all in your way."

Gualtiero, Fidelia's father, now comes on, and, with the gathering crowd of villagers, enters the church. The beginning of the voluntary on the organ is heard, and over and above this simple diatonic, ecclesiastical tune, come, in skilful and expressive contrast, the remarks of the gipsy girl to Edgar, by which she reminds him that she has opened to his nature the delights of an intense full-blooded love in place of the mildly inocuous affection of peasant girls. "Trot along, good little boy," she sings, "and go to church." Edgar's feeling about the matter is quickly shown by his emphatic "Silence, demon!" which comes out43 like the crack of a whip. But Tigrana only laughs at him.

As Tigrana turns to go into the inn she is stopped by Frank, the brother of Fidelia. Frank is in love with the gipsy girl, and from him we learn that fifteen years ago she was abandoned in the village. Questioned as to her doings, Tigrana tells Frank that he is a tiresome bore, while he proceeds with the not very tactful method of reproaching her for her ingratitude. "You were the child of us all," he sings, "and we did not know we were nursing a viper in our midst."

Tigrana, who is not given to wasting much time with preliminaries, tells Frank that if he has any regard for his virtue he had better not be seen talking to her; and she goes towards the inn. Frank bursts out with the confession that he has tried to tear her out of his heart, but although she brings nothing but grief to him she remains there in full possession.

From the church comes the sound of a fragment of a motet, begun by the sopranos and swelling out afterwards in a six-part chorus. Tigrana sits on the table outside the inn and jeers at the piety of those peasants who, not being able to find room in the church, kneel outside and join in the devotion. To her dembal she sings a quaint and springy sort of tune which is thoroughly impudent in character. With a murmur of disapproval, which afterwards grows into a demand, the peasants indignantly ask her to desist from her frivolity. As she proceeds with her melody the peasants threaten to take stronger measures to stop the interruption to their prayers, and Edgar, coming out, rushes44 at once to Tigrana's defence. This open devotion to her cause apparently surprises the villagers greatly, and Edgar finds himself called upon at once to make up his somewhat vacillating mind. With rather curious and certainly sudden access of ardour, he rails against his lot, and curses the home of his fathers. Egged on to a species of frenzy, he rushes into the house and comes out bearing an ember from the hearth. In spite of the efforts of the villagers to restrain his mad impulse he flings the brand into the house, and clasping Tigrana to him, announces his intention of fleeing with her. Frank then rushes on to prevent their departure, and the two young men draw their daggers. A lull in the fray is caused by the entrance of Gualtiero and Fidelia from the church; and the old man's counsel for peace backed up by pious ejaculations from the crowd, seems likely at first to prevail. But Tigrana puts an end to Edgar's hesitation, and he attacks Frank with fury. Frank is badly wounded, and falls in his father's arms as the chorus curse Edgar for a reprobate, and the curtain falls as the house, now well ablaze, lights up the scene with its lurid glare.

The second act shows us a terrace in a garden with the brilliantly lighted rooms of a sumptuous mansion glimmering in the distance. The stillness of the night is broken by the sounds of revelry, more languorous than strident. The chorus, which sing of the splendour of the night, is made up of two sopranos, an alto, two tenors, and a bass; and the essentially nervous, close harmonies—the light detached phrase begins with a chord of the 13th—establish the atmosphere. There45 is some fine and characteristic music in this rather long scene between Edgar and Tigrana, who have, it is easy to understand, been partaking too freely of the joys which soon pall. Edgar is weary of his enervating surroundings, and his thoughts turn to the glory of the April dawn and the calm love of Fidelia. Tigrana taunts him with reproaches, and there follow the inevitable mutual recriminations. In vain does she bring her fascinations to bear upon her lover. The sound of drums and the march of soldiers is heard, and Edgar calls out to them as they pass to stay their march and partake of his hospitality. Tigrana at once begins to be suspicious. Frank, as it turns out, is the captain of the band. Edgar hails him with joy as the saviour of the situation. "Frank, forgive me," he cries. "You alone can save me and enable me to redeem my past." Tigrana is distracted, but she is powerless to prevent Edgar's departure, and with a menacing gesture she sees her lover go, a characteristic phrase from the chorus forming the background to the last utterances of the principals concerned in this short and not particularly convincing act.

The third act is prefaced with a short prelude of melancholy mould. The rising curtain discloses a courtyard within a fortress at Courtray. In the battle which raged round this castle, the Flemish, it will be remembered, with very few numbers—and these only armed with agricultural implements for the most part—conquered the French army led by Philip Le Bel. Their opponents were decoyed into a sort of marshy swamp, and were not only hampered by their large46 retinue, which included carriages, women-kind, and all sorts of paraphernalia, but imagined that they were only to meet a handful of ignorant churls. There is a chapel on one side of the scene, and distant trumpet calls are heard as a funeral cortège proceeds to range itself around a hearse, and the monks in the procession light tapers.

Preceded by a draped banner, the soldiers bear on the body of a knight, fully armed, which they place on the hearse and then deck it with flowers and wreaths. Standing apart from the crowd are Frank and a monk, while in the background are seen Fidelia and her father. The chorus chant a Requiescat, and then Fidelia sings a most moving and pathetic farewell, for the armed knight is Edgar. It may be stated, however, that the monk who stands apart is really Edgar, who, for no very clear or convincing reason, has chosen to be a witness of his supposed funeral celebration.

Frank now adds his praise to the farewell of Fidelia, and extols in an oration the splendid courage of the man Edgar who died for his fatherland. Then the monk does a seemingly strange and unwarrantable thing. He tells the soldiers that their hero, before death, directed that all his misdeeds should be proclaimed publicly, in order that his life might set an example in true penitence. The monk then relates the story of Edgar's past life, and discloses among other details the relations existing between the dead man and Tigrana.

PUCCINI IN HIS STUDY AT HIS MILAN HOUSE

Specially photographed by Adolfo Ermini, Milan

Fidelia, filled with horror at the supposed treachery, boldly asks how the soldiers dare to listen to this47 besmirching of their leader's honour. The soldiers, however, appear to believe the tale, and make an attempt to drag the body off to throw it to the vultures. The monk is touched by the loyalty of Fidelia, who is prepared to defend, with her life if needs be, the body of her hero. "By death," she cries, "he has expiated his sins. Leave me to watch him through the night, and my father and I will bear his body away in the morning and find for it some resting-place in his native village." The monk then kneels for a space by Fidelia; and the soldiers, touched by her devotion, move off, and Fidelia leaves with her father.

Tigrana now enters, and, like Fidelia, would pay her tribute of respect to the dead man. Frank and the monk, however, after a little consultation, put a little plan of theirs into operation, and approach Tigrana. "Would that I were the object of your grief," says Frank. "One tear of yours is worth a thousand pearls." The monk then comes out with some rather plainer speaking, and deliberately bribes the erstwhile gipsy with some jewels if she will do their bidding. Tigrana very readily falls into the trap and the soldiers are recalled. The monk now calls on Tigrana to speak out, and prove that Edgar was a traitor to his country. She hesitates for a moment, but finally acknowledges that the accusation is true. In righteous anger the soldiers rush to the hearse and drag the body away, but the armour is found to be merely the empty pieces and no body is encased therein. Fidelia and her father now come on, and the fraud is disclosed to them. "Yes," cries the monk, throwing back his48 cowl, "for Edgar lives." Fidelia, at first stunned by the joyful discovery that her lover lives, throws herself into his arms, and Tigrana is spurned by the soldiers. With an exclamation, "I am redeemed, only love is the real truth," Edgar leads Fidelia towards the castle. Like a tiger cat, Tigrana follows them, and with a savage leap stabs Fidelia, who dies instantly. Edgar and Frank turn and seize the murderess, and the soldiers, with a bloodthirsty cry, hale her off to instant execution. With a cry of despair Edgar falls senseless across Fidelia's body.

PUCCINI IN HIS MILAN HOUSE

Specially photographed by Adolfo Ermini, Milan

Notwithstanding many serious shortcomings, Edgar, as a lyric drama, contains much that is sincere and appropriate. It was not a success on its first representation, and the blame was laid for the most part on the libretto. Seeing, however, in the history of opera how many a worse book has passed muster, it is a little curious that Puccini's second work should have been so completely laid on the shelf. It is not the lack of dramatic qualities that make the story of Edgar a poor one; it is rather that the story, as a play, does not contain enough of characterisation to really retain the interest. In spite of the weak third act, with its supposed dead body, and the hero in disguise, the music of this section, both from its wealth of melody, its treatment, and above all its powerful expressive qualities, stands as the best in the work. A finer or more moving scene than that of Fidelia's farewell is hardly to be found in the whole range of what may be termed modern opera. Taken as it stands Edgar proved that Puccini had emphatically progressed49 beyond his achievement of Le Villi. Amid the sweet notes of love there come strong and virile expressions of anger, tumult and indignation, but the main theme is kept clearly to the front with all that force that stands as the leading characteristic of Italian opera, old or new—definite and direct vocal expression.

Puccini himself had, and still has by all accounts, a very warm affection for this Edgar of his; and it is not at all unlikely that a revised version may be seen in the near future. Indeed, as it stands, it might very well be permitted the test of a revival.

Auber was the first opera-composer to be attracted by the Abbé Prévost's famous romance Manon Lescaut. It is one of those vivid stories of love and passion which have ever made an appeal to those in search of a theme for musical expression. As drama it has a very close connection with life in general, and its human interest has that full flesh-and-blood quality which gives it a certain quick vitality. Sad and sordid it may be; but the story of the wayward Manon, as fascinating a black sheep as ever graced the pages of fiction—or history—is one which is likely to remain in the common stock of tales which provides novelists with material for practically all time.

The chief romances of the Abbé are the Mémoires d'un Homme de Qualité, Cleveland, and Doyen de Killerine (the two latter, by the way, books which show the result of his sojourn in England). While these exhibit certain well-marked qualities, they are completely cast into the shade by Manon Lescaut, his masterpiece, and one of the greatest novels of the eighteenth century, while, from its characterisation, it may be pointed to as the father of the modern novel. The Chevalier des51 Grieux is an embodiment of the saying "Love first and the rest nowhere," and it is curious that the Abbé made a French translation of Dryden's once famous play on the same theme, All for Love. Manon, as a creation, is a triumph, one of the most remarkable heroines in fiction, springing red-hot as it were from the imagination of the wandering scholar who brought her into existence. It is all the more extraordinary that the novel which at once makes an appeal by its interest and sincerity, but which repays study as a work of art, should have been a sort of appendix to his first work.

Some years after Auber's opera had been laid on the shelf—it never attained to any great popularity—Massenet, a notable "modern" French composer, found by means of its story the expression of quite the best that was in him. Since Carmen modern French opera has no such masterpiece of its kind to show. Massenet's Manon was produced in 1884, and in the fulness of time Puccini turned to the same story, and after planning his own scenario, commissioned Domenico Oliva—dramatic critic of the Journal d'Italia of Rome, and author of a play Robespierre which had attained no little success—to write the "book." This was afterwards so drastically altered and remodelled by Puccini, in consultation with Ricordi, the publisher, that in justice to Oliva, his name as the author of the libretto was removed from the published score.

It was produced in 1893 at the Regio Theatre, Turin, on the 1st of February, conducted by Alexander Pomé, and cast as follows:

| Manon | Ferrani. |

| The Dancing Master | Ceresoli. |

| Des Grieux | Cremonini. |

| Lescaut | Moro. |

| Geronte | Polonini. |

| Edmund | Rassini. |

For a new work by a composer whose reputation at that time, much to the wonderment of native judges and musicians, had not traversed beyond Italy, its production in England was remarkably quick. It was given the next year, on May 14, 1894, at Covent Garden with the following cast, comprising a special company of Italian singers brought together by Messrs. Ricordi, of which the exceptionally fresh chorus appears to have been the chief point of excellence:

| Manon | Olghina. |

| Des Grieux | Beduschi. |

| Lescaut | Pini-Corsi. |