Transcriber’s Notes:

The original spelling, hyphenation, and punctuation have been retained, with the exception of apparent typographical errors which have been corrected.

For convenience, a table of contents, which is not present in the original, has been included.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE BEGINNING OF A PLOT. | 5 |

| II. | BACK FROM THE DEAD. | 20 |

| III. | JIMMY DURYEA’S DARING. | 28 |

| IV. | THROWING THE GAUNTLET. | 37 |

| V. | THE GHOST OF JIMMY. | 46 |

| VI. | NICK MEETS DEFIANCE. | 55 |

| VII. | WHEN A MAN IS DESPERATE. | 65 |

| VIII. | PLOTTING AGAINST A PLOTTER. | 74 |

| IX. | EXCITEMENT IN THE NIGHT. | 83 |

| X. | A PLOT MOST FOUL | 93 |

| XI. | THE DIAMOND NECKLACE. | 103 |

| XII. | THE REVELATIONS OF NAN. | 112 |

| XIII. | THE LAYING OF THE GHOST. | 121 |

| XIV. | THE STOLEN IDENTITY. | 129 |

| XV. | A WOMAN OF MYSTERY. | 145 |

| XVI. | GOING AFTER JUNO. | 154 |

| XVII. | JUNO. | 163 |

| XVIII. | A DANGEROUS WOMAN. | 172 |

| XIX. | TRAILED BY FATALITIES. | 181 |

| XX. | THE SIREN EXERTS HER SKILL. | 190 |

| XXI. | THE SIREN AT WORK. | 199 |

| XXII. | A SECRET MISSION. | 218 |

| XXIII. | THE WORK OF A SECRET AGENT. | 234 |

| XXIV. | THE AMBASSADOR’S CABINET. | 243 |

| XXV. | THE HOLLOW BEDPOST. | 252 |

| XXVI. | THE WOMAN SPY. | 261 |

| XXVII. | IN THE NET OF A SIREN. | 270 |

| XXVIII. | A FIGHT IN THE STREET. | 287 |

| XXIX. | MURDER. | 296 |

| XXX. | BARE-FACED JIMMY’S DOUBLE. | 305 |

NICK CARTER STORIES

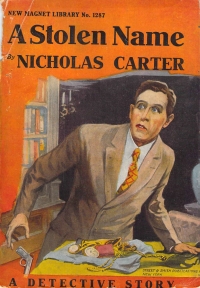

New Magnet Library

Not a Dull Book in This List

ALL BY NICHOLAS CARTER

Nick Carter stands for an interesting detective story. The fact that the books in this line are so uniformly good is entirely due to the work of a specialist. The man who wrote these stories produced no other type of fiction. His mind was concentrated upon the creation of new plots and situations in which his hero emerged triumphantly from all sorts of troubles and landed the criminal just where he should be—behind the bars.

The author of these stories knew more about writing detective stories than any other single person.

Following is a list of the best Nick Carter stories. They have been selected with extreme care, and we unhesitatingly recommend each of them as being fully as interesting as any detective story between cloth covers which sells at ten times the price.

If you do not know Nick Carter, buy a copy of any of the New Magnet Library books, and get acquainted. He will surprise and delight you.

| ALL TITLES ALWAYS IN PRINT | |

| 901—A Weird Treasure | 902—The Middle Link |

| 903—To the Ends of the Earth | 904—When Honors Pall |

| 905—The Yellow Brand | 906—A New Serpent in Eden |

| 907—When Brave Men Tremble | 908—A Test of Courage |

| 909—Where Peril Beckons | 910—The Gargoni Girdle |

| 911—Rascals & Co. | 912—Too Late to Talk |

| 913—Satan’s Apt Pupil | 914—The Girl Prisoner |

| 915—The Danger of Folly | 916—One Shipwreck Too Many |

| 917—Scourged by Fear | 918—The Red Plague |

| 919—Scoundrels Rampant | 920—From Clew to Clew |

| 921—When Rogues Conspire | 922—Twelve in a Grave |

| 923—The Great Opium Case | 924—A Conspiracy of Rumors |

| 925—A Klondike Claim | 926—The Evil Formula |

| 927—The Man of Many Faces | 928—The Great Enigma |

| 929—The Burden of Proof | 930—The Stolen Brain |

| 931—A Titled Counterfeiter | 932—The Magic Necklace |

| 933—’Round the World for a Quarter | 934—Over the Edge of the World |

| 935—In the Grip of Fate | 936—The Case of Many Clews |

| 937—The Sealed Door | 938—Nick Carter and the Green Goods Men |

| 939—The Man Without a Will | 940—Tracked Across the Atlantic |

| 941—A Clew from the Unknown | 942—The Crime of a Countess |

| 943—A Mixed-up Mess | 944—The Great Money-order Swindle |

| 945—The Adder’s Brood | 946—A Wall Street Haul |

| 947—For a Pawned Crown | 948—Sealed Orders |

| 949—The Hate that Kills | 950—The American Marquis |

| 951—The Needy Nine | 952—Fighting Against Millions |

| 953—Outlaws of the Blue | 954—The Old Detective’s Pupil |

| 955—Found in the Jungle | 956—The Mysterious Mail Robbery |

| 957—Broken Bars | 958—A Fair Criminal |

| 959—Won by Magic | 960—The Piano Box Mystery[ii] |

| 961—The Man They Held Back | 962—A Millionaire Partner |

| 963—A Pressing Peril | 964—An Australian Klondike |

| 965—The Sultan’s Pearls | 966—The Double Shuffle Club |

| 967—Paying the Price | 968—A Woman’s Hand |

| 969—A Network of Crime | 970—At Thompson’s Ranch |

| 971—The Crossed Needles | 972—The Diamond Mine Case |

| 973—Blood Will Tell | 974—An Accidental Password |

| 975—The Crook’s Double | 976—Two Plus Two |

| 977—The Yellow Label | 978—The Clever Celestial |

| 979—The Amphitheater Plot | 980—Gideon Drexel’s Millions |

| 981—Death in Life | 982—A Stolen Identity |

| 983—Evidence by Telephone | 984—The Twelve Tin Boxes |

| 985—Clew Against Clew | 986—Lady Velvet |

| 987—Playing a Bold Game | 988—A Dead Man’s Grip |

| 989—Snarled Identities | 990—A Deposit Vault Puzzle |

| 991—The Crescent Brotherhood | 992—The Stolen Pay Train |

| 993—The Sea Fox | 994—Wanted by Two Clients |

| 995—The Van Alstine Case | 996—Check No. 777 |

| 997—Partners in Peril | 998—Nick Carter’s Clever Protégé |

| 999—The Sign of the Crossed Knives | 1000—The Man Who Vanished |

| 1001—A Battle for the Right | 1002—A Game of Craft |

| 1003—Nick Carter’s Retainer | 1004—Caught in the Toils |

| 1005—A Broken Bond | 1006—The Crime of the French Café |

| 1007—The Man Who Stole Millions | 1008—The Twelve Wise Men |

| 1009—Hidden Foes | 1010—A Gamblers’ Syndicate |

| 1011—A Chance Discovery | 1012—Among the Counterfeiters |

| 1013—A Threefold Disappearance | 1014—At Odds with Scotland Yard |

| 1015—A Princess of Crime | 1016—Found on the Beach |

| 1017—A Spinner of Death | 1018—The Detective’s Pretty Neighbor |

| 1019—A Bogus Clew | 1020—The Puzzle of Five Pistols |

| 1021—The Secret of the Marble Mantel | 1022—A Bite of an Apple |

| 1023—A Triple Crime | 1024—The Stolen Race Horse |

| 1025—Wildfire | 1026—A Herald Personal |

| 1027—The Finger of Suspicion | 1028—The Crimson Clew |

| 1029—Nick Carter Down East | 1030—The Chain of Clews |

| 1031—A Victim of Circumstances | 1032—Brought to Bay |

| 1033—The Dynamite Trap | 1034—A Scrap of Black Lace |

| 1035—The Woman of Evil | 1036—A Legacy of Hate |

| 1037—A Trusted Rogue | 1038—Man Against Man |

| 1039—The Demons of the Night | 1040—The Brotherhood of Death |

| 1041—At the Knife’s Point | 1042—A Cry for Help |

| 1043—A Stroke of Policy | 1044—Hounded to Death |

| 1045—A Bargain in Crime | 1046—The Fatal Prescription |

| 1047—The Man of Iron | 1048—An Amazing Scoundrel |

| 1049—The Chain of Evidence | 1050—Paid with Death |

| 1051—A Fight for a Throne | 1052—The Woman of Steel |

| 1053—The Seal of Death | 1054—The Human Fiend |

| 1055—A Desperate Chance | 1056—A Chase in the Dark |

| 1057—The Snare and the Game | 1058—The Murray Hill Mystery |

| 1059—Nick Carter’s Close Call | 1060—The Missing Cotton King |

| 1061—A Game of Plots | 1062—The Prince of Liars |

| 1063—The Man at the Window | 1064—The Red League |

| 1065—The Price of a Secret | 1066—The Worst Case on Record |

| 1067—From Peril to Peril | 1068—The Seal of Silence |

| 1069—Nick Carter’s Chinese Puzzle | 1070—A Blackmailer’s Bluff |

| 1071—Heard in the Dark | 1072—A Checkmated Scoundrel |

| 1073—The Cashier’s Secret | 1074—Behind a Mask |

A STOLEN NAME

OR

The Man Who Defied Nick Carter

By NICHOLAS CARTER

Author of “The Taxicab Riddle,” “Nick Carter’s Last Card,” “Bandits of the Air,” etc.

STREET & SMITH PUBLICATIONS

INCORPORATED

79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York

Copyright, 1910

By STREET & SMITH

A Stolen Name

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages, including the Scandinavian.

Printed in the U.S.A.

A STOLEN NAME.

CHAPTER I.

THE BEGINNING OF A PLOT.

Bare-Faced Jimmy, so-called gentleman crook, expert cracksman, and a master criminal in any department of the underworld to which he cared to devote his attention, leaned backward in his chair until it tilted against the wall behind him, blew a cloud of Perfecto smoke ceilingward, and remarked:

“It will be the easiest thing in the world, Juno. If the objective point were a fortune—even a moderate one; if the thing contemplated included the theft of a single dollar, in cash or in estate, it would be different; but it doesn’t. No, it does not. Really, Juno, if one pauses to think seriously about it, from that point of view, it is almost laughable.”

“That is why I have been smiling at the idea ever since you mentioned it,” returned the woman, applying a lighted match to a cigarette with all the grace and abandon of one who had been long accustomed to the practice.

“As a matter of fact,” Jimmy continued, as if he had not heard her remark, “if I do decide to undertake it, the only things that I steal will be a lot of debts; and who ever heard of stealing debts? Eh?”

“There certainly is novelty in the thought,” was the quick reply. “If some gracious person had done you the honor to steal yours, long ago——”

“Oh, yes, my dear; that is quite true; only we won’t go into the ‘long ago’ matters, just now, if you please.”

The woman shrugged her shoulders and picked up from her lap a book that she had been reading. For a time she devoted her attention to the pages, and then her companion broke the silence again.

“I think I’ll do it,” he said decidedly. “I see great possibilities in the adventure. Juno, will you be good enough to lay that book aside for a few moments, and to give me your undivided attention?”

“Gladly,” she replied, “if you will condescend to speak out plainly, instead of confining yourself to generalities.”

“All right, my dear; here goes. In the State of Virginia, bordering on the Potomac River, and washed by the waters of two other streams—which by courtesy are also called rivers—lies an estate which consists of something more than eight hundred acres. The title to that estate is in the name of James Ledger Dinwiddie, who——”

“Who, at the present moment lies dead in the adjoining room in this house,” she interrupted him; but he only chuckled as he responded:

“On the contrary, he is seated here before you, now; he is talking with you; he is referring to that dear old plantation in dearer old Virginia which, ever since the days of Bushrod Washington, has been called by the name of Kingsgift—the Lord only knows why, unless some dead and forgotten king gave it as a present to the original Dinwiddie. Henceforth, my dear, I am Ledger Dinwiddie, owner of an estate in Virginia that is mortgaged for more than it was ever worth; for much more than it would ever bring at a forced sale. I am also the undisputed owner of a choice collection of debts, of an old colonial house that is now falling into ruins, of numerous other buildings that are in various stages of dilapidation, and of numerous other things of the same sort, all of which are not only entirely worthless, but are really much worse than worthless; and there you are.”

“Will you tell me, Jimmy, just what you expect to gain, then, by this remarkable adventure, as you call it?” the woman asked quizzically.

“Decidedly I will tell you. I gain the one thing I need most, just now—a name. My own—but I have never told you what my own really was, have I? No; and there is no use going into that, now—but my own[8] name has been so long abandoned that I have forgotten the use of it; especially the application of it. The name that has been given me by the police of various localities, isn’t sufficiently high-sounding; and——”

“No. Bare-Faced Jimmy is hardly a name to have engraved upon one’s cards,” she interrupted him.

“——and, as I was saying, James Duryea, who has been called Bare-Faced Jimmy, is popularly supposed to lie buried on an island in the Sound, just off South Norwalk, Connecticut. I would much rather that the police should not be undeceived about that, and so we will let Jimmy Duryea, cracksman, lie there and rot; eh?”

“If you please. I don’t mind. A rose by any other name, you know.”

“Yes; I know. And that reminds me. In the future I will thank you to address me as Ledger. Eh? By Jove! Juno, that chap in there was the most unbalanced ledger I ever saw in my life. If he hadn’t sort of come to, during the last hours of his life, and told all he ever knew about himself and his people, this idea would never have occurred to me.”

“It looks to me like a fool idea, anyhow,” she commented, with a toss of her beautiful and shapely head, crowned as it was with a wealth of raven-black hair. Juno was undeniably a beautiful woman—a fact of which she was perfectly well aware.

“Fool idea?” he retorted. “Not much. It’s a splendid one. It is the idea of my life, and it is worth about three or four times as much as it would have been had the chap in there left a million in money and unencumbered estates behind him when he died. I would rather have his debts than a fortune that he might have left. Really, I don’t think that I would have undertaken the thing if he had left property that was worth anything.”

“Why?”

“Why, to what, Juno?”

“Why is the name and the identity of that poor fellow worth more to you, so, than if he had left a fortune behind him?”

“Why? Can you, my dear, ask such a question as that?”

“I do ask it.”

“Then know this: Nobody will want what Dinwiddie has left behind him. No one will be desirous of shouldering his debts; and consequently nobody will step forward to dispute the rights that I shall assert belong to me. Word will travel around the neighborhood, and throughout the county, that Ledger Dinwiddie has come back; then there will be a few convulsive shrugs of a few shoulders, a score or so of knowing winks—and that will be about all. On the[10] other hand, if there was property, there would be a hundred disinterested persons, neighbors and otherwise, who would find a chance to doubt if I were the real Dinwiddie returned to what had once been his own.”

“But what do you get out of it, Jimmy?”

“I get a name, my dear; an old, old name; an older lineage, than which there is none better in the Old Dominion; an ancestry that is unimpeachable; a reputation which stands for gentility, and which has stood for gentility for generations; a career, all made in a moment, but which is, nevertheless, three centuries old; an established place in the world which none can deny me—Heaven knows that I need one just now; and a safe refuge in which I can hide myself for the rest of my natural life, without the trouble of attempting to disguise my face, or my mannerisms.”

“All the same, Jimmy, there are plenty of people in the world, honest men and crooks, policemen and judges on the bench, lawyers and ex-convicts, who will quickly recognize the features of Jimmy Duryea, if those features happen to be seen.”

“Juno, that is just the point; they won’t. Ledger Dinwiddie will bear a strong resemblance to the late lamented Bare-Faced Jimmy, to be sure, but nobody will ever think of associating the two; never. Besides, if the necessity should arise, Ledger Dinwiddie[11] could establish his identity beyond question. People could be found who knew him when he was a boy.”

“And you might even claim, if you choose, that the defunct Jimmy was a distant relation who went to the bad in his early youth, and who had been cast off by ‘the family,’” said Juno.

“Precisely. Not at all a bad idea.”

“Well, what then?”

“Everything then, Juno. Like Monte Cristo, the world will be mine. I will only have to reach out my two hands and take it. And with my accomplishments I do not anticipate that it will be a difficult task to do so.”

“Probably not—with your accomplishments.”

“It will never occur to any of those Virginians, up there, that a man would be ass enough to lay claim to a worthless estate, encumbered by unnumbered debts; to a broken fortune—and all that. They will accept me on the spot, and without asking a question.”

“Yet, Jimmy, you do not in the least resemble that dead man in there.”

“I know it. What of it?”

“There may be a few persons left alive, at or near Kingsgift, who will remember the young man who left his home in Virginia, so long ago.”

“Bah! Nonsense, my dear. They will look at me and exclaim. ‘How you have changed!’ or, ‘You’re[12] right smart altered since you went away, Ledger.’ But to offset that, there will be dozens who do not remember at all how Dinwiddie really looked, who will declare, ‘Why, boy, I’d have known you anywhere. You ain’t a mite changed since you was a leetle chap, so high.’ That is the way of the world, Juno.”

“But what will you do with the name, and with the mortgaged estates, when you get them?” Juno asked lightly. “Considering that part of it as settled, for you generally accomplish whatever you undertake to do, what will you do with it all?”

“I’ll make your fortune and mine. I’ll square Dinwiddie with the people around there, and tell them all what a great man I intend to make of myself. I’ll pay off a year’s interest on the mortgages and other debts, and make out new papers, just to give them confidence in me. When that is done, I’ll be ready for the real work of—succeeding.”

“Succeeding at what?”

“At making a fortune.”

“And you really think that you can do it?”

“With such a name, such a lineage, such a reputation for gentility? Of course I can do it.”

“It doesn’t strike me that people will be any more eager to lend you money——”

“Lend me money? I don’t want them to do that.”

“Then how——”

“I shall take it. If they accept me, they must take the consequences.”

“Do you mean that you will do it in the old way?”

“Sure. What other way do I know?”

“What if you should get caught at it, Jimmy?”

“Caught at it? Ledger Dinwiddie caught at burglary? At thievery? What an absurd idea! Oh, no, I won’t get caught at it. Not at all. And the world will open itself wide, inviting me to take it. I’ll have a winter home for you, in Washington; I’ll get those fools to send me to Congress, and—— You’ll see!”

Such was the beginning of the “Great Coup” undertaken by James Duryea, alias Bare-Faced Jimmy, the gentleman crook, alias Howard Drummond, one-time gentleman, graduate of Rugby and Cambridge, ex-officer in the dragoons, and ex- a lot of other things which had come to him by inheritance.

But Jimmy had run the gamut of his short, but varied career.

Nothing had been too swift for him to overtake it, to distance it, and finally to wear out its usefulness, and finally his own, too.

Once, according to Nick Carter’s records, the man had really tried to reform; “had made a stab at it,” as he expressed it; but the old temptations had been too strong for him; the “call of the contest” had proved too alluring. The desire to pit his own wit against[14] the representatives of law and order had overcome the better self that reposed somewhere within the strange complexity of this man, and he had gone again, deliberately, into the life of the underworld.

The woman who was seated upon the chair opposite, and to whom his conversation was addressed, had proved herself to be the only person of whom Jimmy had ever stood in the least in awe.

The name by which Jimmy addressed her, was one that he had bestowed upon her himself.

She had never been known by that name to any other person than this man who had just determined to steal a birthright, although there were half a dozen aliases by which she had been known to the authorities of Paris, Vienna, Berlin, St. Petersburg, and London; and under each one of those half dozen aliases she had earned reputations which filled pages of private but official records of the secret police of five different nations.

Her dossier had been written down in five languages—and more; and now, as Juno, she had started out to carve a new career for herself, with the aid of Jimmy, whom she respected for his wit, his daring, for his past achievements and the promise he gave of attempting new and greater ones.

These two represented the masculine and the feminine of all that is masterful in the life of rogues; they[15] were the perfection of the imperfect, if the expression may be used.

Jimmy was a handsome man, and one who would be noticeable in any company. He was distinguished in appearance, Chesterfieldian in his manners, graceful in his motions—a somebody in everything that he did, educated, refined by instinct and by early training; he was a graduated crook in every part and branch of the “profession.”

And Juno? Draw her picture for yourself. It cannot be too strongly, too perfectly outlined.

She was of that type of beauty which only the Latin races achieve, and it had been vouchsafed to her in the superlative degree. Her hair was black, beautiful, and there were masses of it. Her complexion was almost fair, but there was just enough of the olive tint to give to the red blood in her cheeks an added warmth. Her eyes were large, luminous, dreamy, or ablaze with eagerness or passion as the case might be. Her figure was perfect, her hands and her feet were “dreams for the contemplation of an artist,” her every motion was lithe, lissome, sinuous, catlike in the sense that she could not have been lacking in grace had she made the effort. Indeed, there was something about Juno’s every act which suggested the black leopard—and that was one of the aliases by which she had one time been known in Paris. Reduced to five words,[16] Juno’s description was entirely comprehended by the expression: She was a beautiful woman.

Juno’s antecedents were no less aristocratic than Jimmy’s.

She, too, had been born and bred within the exclusiveness of the blue-blooded. Her father and her mother had worn titles of distinction; she had been given all the “advantages” when she was a child, and a young woman—she was that, still. She spoke many languages, and spoke each one so perfectly that it was a matter of indifference to her which one she made use of.

In the long-ago, when both had been respectable children, she and Jimmy had played together. Many years after that, when Jimmy had gone to the bad, and Juno had achieved an international reputation in her various lines, they met again—to drift apart as they had done in those early days.

After that there was another lapse of years during which Jimmy had visited South Africa, had married, had drifted to New York with his wife, had been sent to Sing Sing, had been divorced, and then, according to official reports concerning him, had died and was buried on an island in Long Island Sound. During these years Juno had served the Nihilists of Russia, the Socialists of Germany, the secret societies of other nations—during which she had been a spy,[17] also, for these several governments, and had won an international reputation, and become almost everything that a beautiful woman should not be.

But the continent of Europe, and the British Isles, had grown too hot for her. She came to America—and almost the first person she encountered after leaving the steamer that brought her here, was Bare-Faced Jimmy. And this happened within the year that followed upon his supposed death.

“Two souls with but a single thought,” although by no means a sentimental one, might well have applied to them; the single thought being their desire to victimize the rest of mankind.

“Let’s strike up a partnership, Juno,” Jimmy had said to her. “Together, with your craftiness and my skill, nothing can stop us. Let’s strike up a partnership;” and she had replied:

“Very good, Jimmy; but a minister, not a lawyer, shall draw the contract.”

And so they were married—strangely enough, under their right names, too.

Jimmy had more than twenty thousand dollars cached away in a secret hiding place; Juno possessed half as much more. The marriage occurred in the late fall, and they went South, to one of the Florida beaches, where they secured a villa, and where they passed what was really a honeymoon.

When issuing from their cottage door one morning, they had found the insensible form of a man upon their doorstep.

One may be a crook, a burglar, and all that, and still possess much kindness of heart; two may be so, and these two were.

Together they carried their unconscious burden inside the cottage, summoned the one servant who waited upon their wants, and attended to the stricken man.

They did not ask where he came from, nor how it happened that he had fallen upon their doorstep in his present condition; and he could not have informed them, then, if the questions had been asked.

But they ministered to him; they kept him there and cared for him, making no inquiries concerning him, since by doing so they would have attracted attention to themselves, which was the one great thing they desired to avoid.

But the stricken man had arrived at the end of his journey. He had fallen upon their doorstep to die, and die he did, after three weeks, easily, painlessly, composedly, and tenderly cared for until the last, by these two bits of flotsam.

And there had been some hours of clearness of vision, of return to memory, before death claimed its prize. He had told them his name, and all about himself—and[19] also that nowhere in the world did there remain one person who was nearly enough related to him to care whether he lived or died; that he was the last of his race, in the direct line, and that he bore an old and honored name upon which there had never been a blemish, save that one which poverty imposes.

Ledger Dinwiddie died in the spare bedroom of that cottage inhabited by these two products of the underworld, cared for during his last hours by two as uncompromising crooks and rogues as ever lived to prey upon mankind.

And so, Ledger Dinwiddie did not die, but lived on again in the person of Bare-Faced Jimmy, who adopted the name and the lineage of his uninvited guest, and who went forth, presently, to assume all the prerogatives which the possession of that name could bestow upon him.

CHAPTER II.

BACK FROM THE DEAD.

“It was four years ago, wasn’t it, Chick, when Bare-Faced Jimmy kept us guessing? You remember Jimmy Duryea, don’t you?” asked Nick Carter of his first assistant, as he lighted a cigar immediately after breakfast, one Monday morning.

“Remember him? I should say I do!” replied Chick, as he selected a cigar from the box on the table. “Bare-Faced Jimmy! The mere mention of that name, Nick, calls up a great many recollections. And that reminds me; I wonder what has become of Nan Nightingale. I have not seen a line about her in any of the papers lately. Has she left the stage?”

“I saw her last evening, at church or, rather, just as we were coming out of church,” replied the detective. “That was why I asked the question.”

“You saw Nan?”

“Yes; and talked with her.”

“And her husband—Smathers was his name, wasn’t it—did you see him, too?”

“No. Smathers—The Man of Many Faces, as he called himself on the vaudeville stage—is dead. He died about a year and a half ago, Nan told me. Jimmy Duryea was her first husband, you know. She got a[21] divorce from him when he was sent to prison, and afterward married Smathers. Smathers has been dead more than a year, and Nan thinks that Jimmy is still alive.”

“Jimmy Duryea alive? Impossible.”

“That is what I told her; but she insists that she saw him—or his ghost.”

“Then it must have been his ghost, Nick. Jimmy has been dead four years. He died soon after you took him off that island in the Sound, near South Norwalk, didn’t he?”

“That was the supposition. That has always been my belief. Do you remember that last stunt of his, Chick?”

“The time he passed himself off as Paran Maxwell, do you mean?”

“Yes.”

“I think we all have cause to remember that incident. Bare-Faced Jimmy was a remarkable chap, Nick, take it all in all.”

“He certainly was. There was a great deal of good in Jimmy. You remember there was a time when I thought he had entirely reformed. Then he made that disappearing act of his from the steamship, and bobbed up, long afterward, on that island. It would be strange if he should appear again, after four years, wouldn’t it?”

“It certainly would; but stranger things than that have happened in our experiences, Nick.”

“Yes. But, somehow, I can’t believe that Jimmy Duryea is alive, now; although Nan is positive about it.”

“Tell me what she said. Tell me about your talk with her. I always liked Nan; and it is a cinch that she could sing. You gave her the right name when you called her Nightingale.”

“Yes. Even Pettis said that.”

“Why did she give up the stage?”

“She didn’t tell me that. I was coming out of the church when some one touched me on the arm, and turning about I saw that it was Nan. Of course I was glad to see her, and I said so.”

“Naturally. She is a sort of protégée of yours, you know. It was through you, Nick, that she quit being a crook and became an honest woman.”

“Softly, Chick. Nan was never really a crook, you know. When she was Jimmy Duryea’s wife he did force her into assisting him in some of his crooked work; but she never had any heart in it. She hasn’t left the stage permanently—only temporarily. She said she desired a rest for a season, and that she had saved up enough money to take it. I guess that is her only reason for not being on the boards at present.”

“But what about Jimmy?”

“It is rather an odd sort of story, but I will tell it to you just as she told it to me and see what you think about it, Chick.”

“All right.”

“During her career on the stage these last four years, Nan has made some splendid acquaintances. I am not referring to people in the ‘profession’ so much as to society people. Nan has become a welcome guest at many an exclusive house, and among the members of the most conservative set.”

“I’m not surprised at that. She is a beautiful woman—there is not another one on the stage who can hold a candle to her, if it comes down to that.”

“You’re right. She is a lady, through and through—to the manner born, so to speak.”

“Sure. And by the way, isn’t that what Jimmy used to say to himself—that he was ‘born, bred, and raised a gentleman’?”

“Yes. And it was true, too.”

“Go ahead about Nan, Nick.”

“Well, it was at the solicitation of some of her society friends that she decided to take a rest for one season. She has saved up a lot of money, as nearly as I can make out, and was invited on a yachting cruise with some of her friends. After that she became the guest of Mrs. Theodore Remsen—and that is where she is staying now.”

“She did get into the ‘upper ten,’ didn’t she?”

“Sure. There isn’t a more exclusive house in the city, or at Newport or Lenox, than the Theodore Remsen’s.”

“I know. Well?”

“Perhaps you know that the Remsens also own a fine residence that fronts on the Hudson River, eh? Not far from Fishkill?”

“I didn’t know it; but that makes no difference. What about it?”

“That is where they are staying just now; and Nan is there with them. She is to be their guest until spring. I believe there is a whole season of pleasure mapped out for Nan, and she is to be made quite the lioness—and all that.”

“I understand. But what has all that got to do with——”

“I am coming to that, Chick. That is what brings me to the rather remarkable tale that Nan told me.”

“I see.”

“To let you in on the ground floor of the story at once, a burglar got into the house up the river, a few nights ago. Nan surprised the burglar at work, made him give up his booty, agreed to say nothing about it to the members of the household, and let him go. But, it appears, that instead of relinquishing his booty and going away empty handed, he only gave up what[25] was in sight, and actually got away with a diamond necklace and some other jewels that belonged to Mrs. Remsen, and to some of her guests. Nan says that what was actually stolen represented close to forty thousand dollars.”

“Jimmy always was discriminating, when it came to a selection of jewels,” said Chick, with a slow smile.

“Right again. But because of the disappearance of those jewels, Nan finds herself in a perplexity. Now, I’ll tell you the story just as it is.”

“All right.”

“It happened last Thursday night. Nan had not been feeling up to the mark that day. She had kept herself rather to herself, since morning. During the day Mrs. Remsen told Nan that she was expecting another guest that evening—a gentleman from the South, named Dinwiddie; Ledger Dinwiddie, to be exact.”

“Rather a high-sounding title, that; eh?”

“Yes. Well, Nan didn’t go down to dinner that evening, so she did not meet the guest, when he arrived. She retired early—that is, she arranged herself in comfortable attire, and kept to her own room, where she passed the time in reading. About eleven o’clock, she tried to compose herself to sleep, but after an hour of vain effort in that line, she decided that it was of no use, and sought another book. There did not happen to be one handy which interested her,[26] and so, garbed in a wrapper, she descended the stairs to the library.”

“It sounds like a chapter out of a book, Nick.”

“It does, for a fact; but you haven’t got the real thing, yet.”

“Go ahead, then.”

“She had bed slippers on her feet, which made no sound as she walked. She crossed the lower hall, after descending the stairs, and stepped into the library, reaching around the jamb of the doorway, as she did so, to switch on the electric lights—and she did it so quickly that she failed to notice that there was a single light already burning in the room.”

“More and more like a novel, Nick.”

“Yes. When she snapped on the lights, a man who had been seated at the table in the middle of the room sprang to his feet—and she found herself looking into the muzzle of a revolver.”

“Well, it wasn’t the first time that Nan has done that. It might have scared most women half to death; but Nan——”

“I rather think that she was more surprised and startled by the appearance of the man himself than by the weapon he held in his hand,” said the detective, interrupting. “The man was Jimmy Duryea; Bare-Faced Jimmy; at least she says it was—and is.”

“And—is?”

“Yes. I’m coming to that.”

“All right.”

“The room was, of course, in a blaze of light. In the man who confronted her, Nan saw the face and features of Jimmy Duryea. On the table where he had been seated was a confused heap of the spoil he had stolen, and was engaged in sorting when Nan interrupted him.”

“And she was looking into the muzzle of a gun,” commented Chick.

“Yes. But it wasn’t that which startled her. It was the face and appearance of the man; of a man whom she supposed to have been dead four years, at least; of the man whom she had once married, and whom she had tenderly loved, until she discovered that he was a crook, when she deserted him and got a divorce.”

“What did she do?”

“What would nine out of ten women do, under like circumstances?” retorted the detective.

“Let out a yell, I suppose.”

“Nan cried out his name. ‘Jimmy!’ she exclaimed; and he dropped the gun to the floor, and called back, ‘Nan!’”

“Tableau!” said Chick.

“Precisely,” said Nick Carter.

CHAPTER III.

JIMMY DURYEA’S DARING.

Chick chuckled softly to himself as he imagined the scene in the library that Nick Carter had just described to him.

“Hold on a minute, Nick,” he said. “Let me get the chronology of those two straight in my mind. Jimmy, according to his own story, told to us four years ago, was, originally, a born aristocrat, the second or third son of somebody-or-other, wasn’t he?”

“Yes. He would never tell who he was; but it is certain that he is well born.”

“So was Nan; and both were English, eh?”

“Yes.”

“Scapegrace Jimmy went to South Africa to finish the sowing of his wild oats, and Nan went there as governess to the children of the South African consul. They met there, and were married. Jimmy was a burglar and a thief, and Nan didn’t suspect it until long after the two had come to this country. Then she found it out, and for a time he compelled her to assist him in his crooked work. Then he got caught, and was sent away, to Sing Sing, and Nan got a divorce. Later, she married Smathers, the man of many faces, and an[29] actor. Then Jimmy got out of prison, thought Nan had peached on him, threatened vengeance, and all that, and intended to kill her, until it happened that you showed him that Nan was not the one who had betrayed him. She wanted to reform, and did so, and Jimmy agreed to let her alone. Then Jimmy got caught, was sent back to England to answer charges against him there, escaped, returned here, and supposedly died on an island in Long Island Sound. That was four years ago. Almost two years ago, Smathers died—I suppose he is really dead, isn’t he?”

“Oh, yes, there is no doubt of that, Chick.”

“And now Nan discovers her former husband, robbing a house where she is a respected guest, and——”

“And that isn’t all of it; not by a long shot.”

“Go ahead, then.”

“Well, it was a tableau for a moment, after the mutual discovery in that library. There was a half mask on the table, which Jimmy had removed while he was sorting the spoil. He always was a cool proposition, you remember.”

“Yes. That is how he got his name of Bare-Faced Jimmy.”

“He didn’t lose his presence of mind, just then, either. He stooped and picked up the gun from the floor, dropped it into one of his pockets—and sat down[30] again upon the chair where he had been seated when she interrupted him.”

“Just like him.”

“The rest of the story I will tell just as Nan told it to me.”

“All right.”

“She said: ‘For a moment I didn’t know what to do. Until that instant it had never occurred to me that Jimmy was alive. I had not a doubt that he was dead. But there he was, as natural as ever, as handsome as ever, as cool and self-contained as ever, and just as daring as he used to be in the old days.’

“‘Sit down, Nan,’ he said to her; and she sat down.

“‘I thought you were dead,’ she told him, and he laughed in his pleasant way, and replied that he was as good as an army of dead men. Then she pointed at the jewels on the table, and at the other things that he had gotten together.

“‘At your old tricks?’ she asked him, and he nodded.

“‘Can’t keep away from it, Nan,’ he told her. ‘It is in my blood, I guess. But what are you doing here? Are you up to the old game, too?’

“Then she told him all about herself, and they talked together for quite a while. The upshot of it was that Jimmy agreed to take the risk of returning all the things to the rooms from which he had taken them,[31] and she promised to wait where she was, until he had done so.”

“That was like Jimmy. Think of the nerve of the fellow, in going back to the rooms he had robbed, to return the jewels to the places where he had found them.”

“That is just the point, Chick; he didn’t.”

“Oh; I see.”

“He replaced a few of the things, but many of them he still kept. He told her, when he came back, that he had returned them, and it wasn’t till the following day that she discovered his deception.”

“I think it is rather remarkable that she trusted him to do it at all.”

“Jimmy could always make Nan believe that the moon was made of green cheese. Well, she promised him that she would say nothing of having found a man in the library, and much less would she mention to any living person who that man really was. So they parted. Nan returned to her room, and retired. Jimmy, presumably, left the house by the way he had entered it.”

“But he didn’t do that, either, eh?”

“No. He didn’t do that, either.”

“What did he do?”

“He sat opposite Nan, at the breakfast table, the[32] following morning, and was introduced to her by their hostess as Mr. Ledger Dinwiddie.”

“Gee!”

“That’s what I said.”

“Say, Nick, if I had heard this story without names being mentioned, I’d have said that Jimmy Duryea would have done that very thing if he were alive.”

“So would I.”

“What did Nan do, when the introduction took place?”

“What could she do? Nothing more than acknowledge the introduction. She couldn’t tell the story of what had happened during the night, with much more credit to herself, than he could have done so; and, besides, just then she supposed that all the stolen property had been returned. It wasn’t till later in the day—some time in the afternoon—that she knew the truth.”

“And then?”

“Then she laid for Jimmy. But he knew that, and avoided her, of course. Finally, she went directly to him, and asked him to walk with her to the stables, and he couldn’t very well refuse to do that. Halfway to the stables, they found a secluded spot, and there she stopped him and told him that unless he returned all the stolen property before the following morning,[33] she would denounce him, no matter what might happen to her.”

“And he made another promise, I suppose?”

“Sure.”

“And kept it in about the same manner?”

“In precisely the same manner.”

“That brings the time to Saturday morning, doesn’t it? The thing happened Thursday night.”

“Yes.”

“What then?”

“Saturday, she went for him again. He told her that there had been no opportunity to replace the stolen jewels the preceding night, but that he would do it that night—Saturday night. Yesterday morning she did not see him at all, but she learned that the jewels had not been returned. Mrs. Remsen asked her to take a motor ride, and she had to go. They came to the city, and decided to remain till to-day—and that is how Nan happened to be at church last night, when I met her.”

“She was alone last night? Mrs. Remsen wasn’t with her?”

“No; she was alone. Nan had been chewing on the thing all day. She didn’t know what to do. She said that she had decided to telephone to me, after church, when she discovered that I was among the members of the congregation.”

“In the meantime I suppose she hasn’t said a word to anybody but you.”

“Not a word.”

“What have you advised her to do?”

“I haven’t advised her—yet. What I did do was to promise to become one of the invited guests at ‘The Birches,’ as they call the Remsen place on the Hudson.”

“I see. So you are going up there, eh?”

“Yes.”

“When?”

“In a couple of hours. I’m going to take the car, and drive there—and you are going with me. Danny will do the driving.”

“Oho! I see! Do you know the Remsens?”

“No. I never met either of them; or any of the family; but Nan said she could fix that part of it all right. Nan was to tell Mrs. Remsen, this morning, that she met an old friend at church, who is to motor out their way to-day, and that she invited him to stop at The Birches. That is all there is to that.”

“You intend to get Jimmy off to one side, and—what?”

“I haven’t decided that point, as yet. You see, there is another complication in the affair. Mrs. Remsen is Theodore Remsen’s second wife. There are two stepchildren at The Birches, a son and a daughter—and Ledger Dinwiddie is supposed to be the future husband[35] of Lenore Remsen. You see, Jimmy Duryea has an assured position at the house, and in the family. He thinks, now, that Nan dare not denounce him, because of the effect that such a denouncement would have upon herself; but with me on the ground——”

“I see. What do you propose to do?”

“I don’t know, Chick, until I get on the ground. It is a queer case all around. Nan is for compelling Jimmy to give up the plunder, and to disappear, without doing anything to him at all. She believes that I am the only person who can accomplish that with him—and, under the circumstances, she is about right, Chick.”

“Yes.”

“So I promised her that I would go there this afternoon. She and Mrs. Remsen—who is a beautiful woman of about Nan’s age—were to return this morning; they are probably halfway there by this time.”

“And you want me with you.”

“Why, yes. I thought you’d like it. Jimmy will realize what he is up against when he sees both of us there.”

“He certainly ought to.”

“I don’t know just what attitude Jimmy will take. You know as well as I do that he never plans a thing of this sort without doing it thoroughly. He is doubtless prepared at every turn, and he may have the bareface to defy me.”

“It wouldn’t surprise me if he did.”

“Nor me, either, Chick.”

“Then what?”

“Oh, we won’t cross any bridges till we get to them.”

“How soon will we start, Nick?”

“In an hour or two.”

CHAPTER IV.

THROWING THE GAUNTLET.

“The Birches,” one of the summer residences of Theodore Remsen, multimillionaire, financier, Wall Street wizard, and one of the recognized powers in the moneyed world, stood, and still stands, a prominent landmark at the location already described.

It stands upon a high bluff overlooking the Hudson, and is approached from the main highway by a winding, macadamized road, which, from the lodge gate to the mansion, is more than a mile in length, and shaded on either side by a double row of white birches; hence its name.

The lawn, directly in front of the house, is laid out in tennis courts, and there Nick Carter and Chick discovered nearly all the guests of the house assembled, when they drove beneath the porte-cochère at four o’clock that Monday afternoon.

Nancy Nightingale had evidently been watching for their arrival, for as Nick stepped down from the car and gave Danny a few directions, he saw her approaching. He went forward to meet her, followed by Chick.

As the detective moved toward her he cast his eyes rapidly over the assembled people—there was a score[38] of them, all told—and thought he saw Jimmy Duryea among them, engaged in an animated conversation with a group of which he appeared to be the centre. But the man’s back was turned, and Nick could not be certain.

Nan, in an outing gown and coat of white flannel, with her black hair and sparkling eyes, looked more beautiful than ever as she approached the two detectives, and her smile of greeting was warmth itself.

She conducted them directly toward the place where Mrs. Remsen was seated, and presented them. She added, after she had done so:

“I told Mrs. Remsen that I had invited you to stop here to call upon us, and now she insists that you shall join our party for as long a time as you can remain.”

After that, with Nan on his arm, Nick passed from group to group on the lawn, acknowledging introductions here and there as he went along. Chick remained with the group that had formed around the hostess.

Presently Nick and his companion approached that particular group of which the man who called himself Ledger Dinwiddie, and whom Nan believed to be Jimmy Duryea, formed one part.

Nan purposely left the introduction to him, for the last of that particular group; and then she said:

“Mr. Dinwiddie, this is an old friend of mine—Mr.[39] Carter;” and Duryea turned about lazily, as if he had not noticed the arrival of a stranger till that moment.

“Glad to know you, Mr. Carter,” he said imperturbably, and with just the faintest trace of a smile on his handsome features; and then he turned back again to the companion with whom he had been talking, and who happened to be the daughter of the house, Miss Lenore Remsen, who was not more than two years younger than her beautiful stepmother.

There was not the slightest trace of recognition in the eyes of Jimmy Duryea when he acknowledged that introduction, although he must have known Nick Carter at once—and he could not have prepared for the sudden appearance of the detective there, unless he had guessed that Nan might communicate with the detective while she was in the city.

Nick was equally reticent. It was no part of his present purpose to force matters; at least he did not intend to do so until the proper moment should arrive; but he did desire to get the gentleman cracksman into conversation, to see how far the assurance of the man would carry him.

Presently he found an opportunity.

It was when Duryea turned to make some general remark to those near him, and Nick chose to reply directly to it.

“I quite agree with you, Mr. Dinwiddie,” he said.[40] “Stolen jewels are difficult things to trace. That is the subject you were discussing, I believe?”

“Yes,” said Nan, before Duryea could reply. “A most remarkable thing happened here, during the night of last Thursday. A necklace, and other jewels, disappeared most mysteriously from the rooms of the owners. But—shhh—we have all agreed to keep very still about it, for the present.”

Duryea laughed softly.

“Perhaps, Miss Nightingale,” he said, “this gentleman will be able to make some valuable suggestions in regard to those missing jewels. He has a namesake in New York who is said to be one of the smartest of living detectives. Isn’t that so, Carter? Eh?”

“Quite so,” replied Nick, looking him directly in the eye. “Only the gentleman to whom you refer is not a namesake. I happen to be the person mentioned myself.”

Duryea’s brows went upward in well-feigned surprise; a chorus of exclamations arose from every side; Nan bit her lips, for she had not intended that Nick should announce himself quite in that manner.

Lenore Remsen turned at once to the detective, and exclaimed:

“Really, Mr. Carter, are you the detective?”

“Yes, Miss Remsen, I really am.”

“Oh, I am so glad. Then you can assist us to recover our jewels.”

“I can try, if it is your wish that I should do so,” replied Nick calmly. “Were you a victim of the robberies, Miss Remsen?”

“Yes, indeed. It was my diamond necklace that was the most valuable thing taken. I must admit that I was very careless about it that night. Instead of putting it away, as usual, I merely dropped it into my jewel box. In the morning it was gone. Don’t you think, Mr. Carter, that it is remarkable how a burglar could get into the house, and go through the rooms as that one did, without leaving a trace of any sort behind him?”

“It does seem so; yes.”

“There wasn’t a trace. Not one; anywhere.”

“Was no one in the house suspected?” asked Nick quietly.

“No one in the——Oh, you mean one of the servants, of course. No; really. The staff of servants that we have in this house are, all of them, old retainers; every one of them has been a long time with us. You know this is the one place which we really call home. We always speak of ‘coming home,’ when we come here. Oh, no, indeed, we could not suspect one of the servants.”

“What is your opinion on the subject, Mr. Dinwiddie?”[42] asked the detective, turning fairly toward Duryea.

The latter smiled, showing his white and even teeth; he twirled his mustache for a moment before he replied, and when he did so it was with deliberation.

“Really,” he said, “you know I am not an authority, Mr. Carter—such as yourself, for example. Still—er—I think I have an opinion, nevertheless. We are all apt to form opinions in such cases, don’t you think, Mr. Carter?”

“Yes. What is yours? You interest me.”

“Do I? Really! You confess yourself to be the great and only Nick Carter, and then do me the honor to care for my opinion!”

“In the hope that it might prove to be an expert one—yes,” replied the detective.

“Expert? Oh, dear, no; not at all expert. Just an opinion.”

“Well, what is it?”

“I shall shock all the ladies present—and some who are not immediately present in this group—when I mention it.”

“Nevertheless——”

“Oh, nevertheless, I shall not hesitate—even at the risk of giving offense. I should venture it as my opinion that the thief in this instance is a woman, whether[43] she happens to be a servant—or one of the guests. There! Have I shocked all of you?”

He laughed easily when he asked the question, as if to take away the sting of it, and he turned his speaking eyes from one to another of the group until he had gone the rounds—and, somehow, he managed to create the impression that he was merely indulging in a joke at their expense.

But there was an uneasy laugh around him, nevertheless.

Lenore Remsen started to her feet, and exclaimed:

“I think that was horrid of you, Ledger! Horrid! The idea of saying such a thing! We shall all be looking askance at each other, from now on. What do you think about it, Miss Nightingale?”

“I should sooner incline to the opinion that the thief was a man, and a guest,” was the deliberate reply; and she added, not without intent, for she was angry, seeing exactly what Duryea had intended to convey to her: “One of the lately arrived guests, at that.”

Lenore clapped her hands.

“That is where you get it back, Ledger,” she exclaimed. “But, really, that was horrid of you, to say such a thing.”

“Who are the lately arrived guests, Miss Nightingale?”[44] asked the detective, without turning his head; and she replied, without hesitation:

“Mr. Dinwiddie is himself the most lately arrived one.”

Duryea laughed aloud.

“Good!” he said. “That is right, too. I arrived that very evening. Now, I wonder if it could have been me? I used to walk in my sleep when I was a child, although I don’t remember that I had the habit of purloining necklaces when I did so. But, then, one never can tell.”

“Indeed one cannot,” retorted Nan. And then, assuming the air of one who was joking, she added: “I should advise a close inspection into your past record, Mr. Dinwiddie, if it is true that you formerly were in the habit of prowling about houses in the night.”

“Gladly!” he exclaimed, joining in the general laugh that followed. “Will you give us the benefit of searching yours, also, Miss Nightingale?”

A slow flush stole into the cheeks and brow of Nan Nightingale, but she was equal to the occasion. She replied:

“It will not be necessary that you should search. Fortunately there is one who has known me many years. Mr. Carter can supply all particulars that may be required.”

“I am afraid,” said Duryea, “that what was intended[45] as a joke all around has taken a serious turn. Let us drop it before we begin to indulge in personalities. Nevertheless, Miss Nightingale, it is well to have a person so renowned as Nick Carter to vouch for one. I only wish that he could perform the same service for me.”

“Perhaps, Mr. Dinwiddie, I might be able to do that, also,” replied Nick quietly. “It is my profession to know something about a great many people who do not suppose that I know them at all. However, as you say, the conversation is taking too serious a turn. I will propose a game of tennis with you, Mr. Dinwiddie; what do you say?”

“Gladly. Come along. Singles?”

“Yes. Singles. There is a vacant court.”

“All right. You’re on. But I warn you, Mr. Carter, I am considered an expert.”

“So much the better. I think I just suggested that about you in quite another line, did I not?”

CHAPTER V.

THE GHOST OF JIMMY.

The game of tennis was over.

There were indications of a shower, and the spectators had scampered toward the wide verandas for shelter, so that Nick Carter and the so-called Ledger Dinwiddie stood alone near one end of the net. It was the opportunity which Nick wanted.

“Well, Jimmy, this is a bolder game than usual, that you are playing, isn’t it?” he asked smilingly.

Duryea raised his eyes to the detective’s without a trace of resentment in them, and also without a vestige of surprise visible. He also raised his brows interrogatively.

“Now, I wonder where in the world you hit upon that name?” he said, in reply, and his expression denoted nothing more nor less than wonderment. “That is what my dear old dad used to call me, Jimmy! James Ledger Dinwiddie is my full name. How’d you hit upon the Jimmy part of it?”

“Oh, come, Jimmy, don’t try to play it out with me. You know it won’t work. You are Jimmy Duryea, all right—and the climate of The Birches isn’t good for you, just now.”

“What the blazes do you mean?” was the indignant ejaculation; and then: “I say, we’ll get caught in that shower, old chap. Come along!”

He seized his racket from the ground and started toward the house; but he had not taken two steps before Nick Carter seized him by the arm and propelled him toward a summerhouse that was near at hand.

“This place will shelter us, Jimmy,” he said coldly. “You come along with me. If you attempt to resist, I shall take you there anyhow, so if you don’t want a scene here on the lawn, come.”

“This is a high-handed——” began Duryea; but the detective interrupted him.

“It’ll be higher-handed if you don’t do as I say,” he remarked; and then the big, advance raindrops began to fall, and they ran together beneath the shelter of the summerhouse.

“Now, what the deuce——”

“Drop it, Jimmy. If you don’t, I’ll put the handcuffs on you now, and take you away with me through this storm. You know that I can do it.”

Bare-Faced Jimmy shrugged his shoulders. Then he laughed. He dropped his lithe and graceful length upon one of the rustic settees, thrust his hands deeply into his pockets, and replied:

“Well, speak your piece, Mr. Carter, since you seem[48] bound to do so. I can listen, and the storm prevents my leaving you. Besides, there is no one to hear us.”

“No; there isn’t any one to overhear us. That is why I pulled you into this place.”

“Extremely kind and thoughtful of you, I’m sure; only, you’d have done better if you had not ventured to thrust yourself upon me at all, wouldn’t you? What the blazes is the matter with you, anyway?”

“Drop it, I say, Jimmy.”

“Gladly—if you’ll tell me what it is that you want me to drop,” was the cool reply. He removed his hands from his pockets long enough to abstract a cigarette case from another one, and to light a cigarette. “Have one? No? Too bad. They’re Russian.”

“Drop the play acting with me, Jimmy.”

“Say, look here, mister man, it was all right for you to make a play with that name that my dad used to call me—at first; but it’s getting tiresome,” exclaimed Duryea, with a fine show of rancour. “I’m Jimmy, all right, only nobody calls me by that name now. I’m Mr. Dinwiddie, particularly to strangers, if you don’t mind. I’ll thank you to address me by that name. What kind of a game are you up to, anyway? Blackmail?”

The effrontery of the man was phenomenal.

Instead of being offended by it, Nick Carter was amused; and he could not resist a small sense of admiration,[49] too, for Duryea’s pluck, under the circumstances. He resolved to meet him on the ground he had selected.

“All right, Mr. Dinwiddie,” he said, smiling. “It is my wish to discuss a certain person whom we both knew in the past. If you prefer to speak of that person in the third person, I see no reason for not humoring you. But, before we continue with the subject, I wish to warn you that I am about through with your pose. I will talk in the third person about that other man, but you’ve got to talk—or something will happen.”

“How melodramatic. Look here, Carter, what are you driving at?”

“I’m driving at one Bare-Faced Jimmy Duryea.”

“Oh; you are! And who might he be? Or who might he have been? Is he a dead one, or is he alive, Mr. Carter? You interest me. Really, you do.”

“He has long since been supposed to be dead, but just now he seems to be very much alive.”

“That’s where you are dead wrong, Carter. Believe me, you are. Dead men do not return. Neither do they discuss tales of themselves. Bare-Faced Jimmy, eh? What a name!”

“It was never more appropriate than at this moment, Jimmy, for if you are not the most barefaced reprobate[50] out of prison, I’ll eat my hat; and that’s quite a compliment.”

“I suppose so. Anyway, I choose to take it so, rather than be offended. But you said he was supposed to be dead—this Bare-Faced Jimmy, as you call him. Why not let him lie? What is the use of stirring up the dead?”

“He has been stealing jewels, that’s all.”

“Oh; has he?”

“Yes. He can stay dead just as long as he pleases if he returns those jewels, and then disappears again, at once.”

“I see. It must be his ghost that you are talking about, Carter.”

“Yes; we’ll call it that. The ghost of Bare-Faced Jimmy.”

“What has he got to do besides return the jewels he has stolen?”

“Beat it. Skip. Get out. Disappear.”

“What! All four, and all at once? Really. Say! Suppose the ghost refuses to walk?”

“He won’t refuse when he realizes just what he is up against.”

“Won’t he? Maybe you wrong him there. Perhaps you do not do this ghost full justice.”

“Perhaps not; but I think I do.”

“Say, Carter, honest, did you ever hear of a ghost that got caught? A real ghost?”

“I don’t think I ever did.”

“Well, you don’t hear of this one’s getting caught, either. If the ghost of Jimmy Duryea stole the jewels you are talking about, the ghost of Jimmy Duryea intends to keep them, and it will go hard with the man or woman—or shall I say the man and woman—who attempts to deprive the ghost of them.”

Nick Carter’s reply was a smile.

“There aren’t any witnesses to this conversation, Carter,” Duryea went on, “so I don’t mind being more or less plain with you for just a moment.”

“I am glad that you have arrived at that conclusion, Jimmy.”

“I’ll tell you this: If anybody has got to ‘drop it,’ as you suggested just now, you are the one to do it. You have bitten off more than you can chew. You just now said that Mr. James Duryea is dead. Let him lie. Mr. Ledger Dinwiddie stands before you, and Mr. Ledger Dinwiddie can prove his descent for generations back, and that without the slightest trouble. If Jimmy Duryea’s ghost walks, Nick Carter won’t be the man to lay it. You can bet your last dollar on that.”

“All the same, I think he will; and to prove it to you, I’ll just clap the irons upon you right now, Jimmy,[52] and as soon as this storm is past I’ll take you where you belong.”

As the detective spoke he produced a pair of handcuffs from one of his pockets, and he held them, jingling before Duryea’s eyes, looking straight at the man.

But Duryea only laughed.

“Put ’em away, Carter,” he said. “You won’t use them; not on me; not to-day, at least.”

“Why not?”

“Because you won’t. That’s reason enough. What do you think would happen, if you should be ass enough to do what you threaten?”

“I think it would be Sing Sing for yours, Jimmy.”

“Not on your life; not much.”

“Why not?”

“Oh, I’ll admit, for the sake of argument, that you may have enough against the aforesaid James Duryea to send him up for the rest of his life; but—you know the old receipt for roasting a hare, don’t you?”

“Well?”

“First catch your hare, Carter. In this case, first catch the man—or shall I say the ghost?”

“Say what you please; it does not alter the circumstance.”

“Doesn’t it? You would find that it did. Admitting that the ghost of Jimmy Duryea is now standing before you, you have already agreed that a ghost was[53] never caught. Do you suppose—you who claim to know me—that I would be fool enough, if I were the man you believe me to be, to stand here and defy you unless I knew exactly what I was doing?”

“You’ve got cheek enough to do almost anything, Jimmy.”

“Yes, and I have got brains enough to have prepared for all the emergencies that might arise, too. I asked you a moment ago if you realized what would happen if you should clap those irons onto me and take me away. You haven’t replied to that question, yet.”

“You answer it, then.”

“You would make a charge against me—as James Duryea. I would establish the fact that I am not James Duryea. All the pictures in the world, no matter whether they are in a rogues’ gallery or not, would have any effect upon the proof that I would be able to offer. I have a long line of ancestry to fall back upon. Ledger Dinwiddie is a personality, widely known in a certain locality where his home is—now. Jimmy Duryea is dead, and buried, and his bones can be dug up, if necessary. Nick Carter, the great detective, would make himself the laughingstock of the whole country.”

“Nick Carter isn’t a bit afraid of doing that, Jimmy.”

“And then, again, you heard my opinion—the one[54] I gave out there on the lawn—about the personality of the thief who stole the jewels. I need only suggest to you that if you should enter that house now, and make a search, you might find the jewels, and you might not; but if you did find them, you would find that everything would point to the identity of the thief as I named it out there.”

“You scoundrel! Do you mean to say——”

“I mean what I have said—no more, no less. You cannot crush me, Carter; you haven’t got it in your power to do so, just now. I would rise, like a phœnix from the ashes, and laugh at you.”

“You think so.”

“No; I know so. I know exactly how thoroughly I have builded this edifice in which I am now living. And so, Mr. Nicholas Carter, the ghost of Bare-Faced Jimmy defies you!”

He stopped and then laughed mockingly.

CHAPTER VI.

NICK MEETS DEFIANCE.

It might occur to the reader to ask: Why did not Nick Carter seize upon his man then and there, put the irons on him, and take him away? The answer is obvious.

The detective knew the man with whom he had to deal, too well.

He realized that Jimmy Duryea would never have placed himself in the present position unless he had been very sure of his ground.

There was no doubt in Nick’s mind that when Jimmy found that Nan had gone to the city, he suspected at once that she would notify Nick Carter of all that had happened at The Birches. The fact that Jimmy had awaited with calmness the arrival of the detective upon the scene was sufficient proof that the former burglar was fairly positive of the ground upon which he stood.

Jimmy denied his identity while admitting it—by implication.

He called himself the ghost of Bare-Faced Jimmy with an irony that was inimitable.

He had stated that Ledger Dinwiddie, the man whom[56] he claimed to be, could establish his identity, with a long line of ancestry, without a doubt, and with very little trouble; and he had asserted that the bones of Jimmy Duryea might be dug up, if necessary, to prove that Jimmy Duryea was really dead.

There is just where the rub came. Jimmy might be bluffing, but again he might be entirely in earnest. Jimmy was a careful one in preparing his coups, and there could be no doubt that he had prepared this one from every available standpoint.

And again, until that meeting with Nan, at the church, Nick Carter himself had believed that Duryea was long since dead and buried.

Nevertheless, Nick Carter was not one to be driven aside from a determination upon which he had studied and decided; and he had decided that this was Jimmy Duryea, and that he must not only give up the stolen property, but must also disappear. If the detective at times appeared to hesitate, it was only because he wished to make himself more sure of his own ground.

“Jimmy,” he said, after a short pause which followed the burglar’s last remark, which was in the nature of a defiance, “you can’t bluff me, and you know you can’t.”

“That is precisely why I am not attempting to do so,” was the quick retort. “You will find, if you persevere far enough, that this is no bluff. I’m in dead earnest.[57] Jimmy Duryea is dead, buried, and gone; Ledger Dinwiddie is very much alive, and is here on the spot, ready to do business. Ledger Dinwiddie owns estates in the South, heavily mortgaged, to be sure; but his, nevertheless. He can prove who he is, and every statement he makes about himself. If you should place me under arrest, you would cause me great inconvenience, to be sure; but you would cause others more than you would me—yourself among the number. Now, you can take that, or leave it.”

“You are covertly making a threat against Nan Nightingale.”

“I am not covertly threatening anybody; but I openly threaten every person, no matter who it is, who attempts to connect me with the former Jimmy Duryea. Now you’ve got it, straight from the shoulder.”

“Jimmy, I’ve got three questions to ask you.”

“Fire away.”

“I won’t go into the details of them till I have asked all of them.”

“Just as you please. I don’t want to hurry you. The storm is almost over, and as soon as it is past I shall deny myself the pleasure of your company, and go to the house.”

“We’ll see about that—when the storm is over.”

“We will see. Now, what are your questions?”

“The first one is this: Will you return those jewels you stole last Thursday night?”

“I have not stolen any jewels, and therefore I cannot return any. Next?”

“Will you, after the jewels are returned to the proper owners, leave this place, and the United States as well, never to return, on condition that I let you go away unmolested?”

“Since I cannot—or will not, if you prefer it so—return the jewels, that last question requires no answer; but I will answer it by saying that I shall remain a guest at this place just so long as it pleases me to do so.”

“The third and last question, is this: Will you promise me never to communicate with Lenore Remsen again, after to-day?”

One quick flash of keen resentment crossed the face of Duryea, when that question was asked; but it was gone as quickly as it appeared. He laughed outright, flicking away the stub of a cigarette as he did so, and producing another one.

“Don’t be an ass, Carter,” he said, rising and turning to cross the summerhouse toward the door through which they could see the people on the veranda of the mansion.

Instantly Nick Carter leaped from the seat he had been occupying, and sprang upon him. He seized[59] him by the arms, pulled his hands behind him, and snapped the handcuffs upon his wrists in that position; and then Nick pulled him away from the door so that there was no chance of being seen from the house.

Beyond the first impulse of resistance, Jimmy made none at all; and when the detective thrust him back again upon the chair where he had been seated before, he looked up with a quiet smile, as if he rather enjoyed the proceeding.

“Jimmy,” said Nick, “I’m not going to monkey with you. You are past all that. You have laid your plans, and you think they will work out to the end. But they won’t. They might do so with some people, but they won’t with me. Now, I offer you your liberty upon those three conditions, and I do it for Nan’s sake, not for yours.”

“Why don’t you marry her, Carter?” was the cool response. “You’re a widower, and she is twice a widow. Why don’t you marry her? You seem to be mightily stuck on her.”

“I am, in the sense that I thoroughly respect a good woman, Jimmy, and Nan is that.”

“She was good enough to go to you and give things away up here, when she supposed that she had the kibosh on me,” sneered Jimmy.

“She did not come to me and give you away, Jimmy. I met her by accident; and even then it was[60] after you had broken your solemn word given to her that night. What has changed you so, Jimmy? You used to be a man of your word, even though you were a crook.”

“I’m not Jimmy, I tell you. Jimmy is dead. Nothing of him remains—unless it is that ghost we have been talking about. Come, Carter, take these irons off me. You can only make trouble for Nan, if I am found in this predicament. She would be the one to suffer; not I.”

“You think so.”

“I know so, Carter. I know whereof I speak. I don’t do things halfway, and you know I do not. I intend to carry off this plan I have laid out, Nick Carter to the contrary, notwithstanding.”

“What does that plan include, Jimmy?”

“If I should tell you, you would know.”

“Do you mean that you would have married that girl, if fortune had not gone against you in the way it has?”

“I intend to marry her, as it is. I have got a name to perpetuate, Carter; the name of Dinwiddie. There is not an older or a better one in this benighted country of yours.”

“Perhaps you will tell me how you came by that name,” suggested the detective; and he was surprised when Duryea laughed aloud.

“I’d like to tell you; by Jove, I would, and no mistake, Carter. It is almost too good to keep. But that would be throwing altogether too much information in your way—and it cannot be done. Look here, Carter, I’ll tell you what I’ll do.”

“Well?”

This was what Nick had been hoping for. He had now got his man to a point where he was tacitly admitting his position, and was doing his share of the talking.

“We’ll admit, for the sake of the circumstance, that I am the ghost of Bare-Faced Jimmy, or at least that I represent the ghost. We’ll admit that the ghost got the diamonds. We’ll admit that the ghost can return them. See?”

“Yes.”

“Well, I’ll confess to you that I badly need those diamonds, in order to carry out my plans, for I am short of money. Nevertheless, since you make such a point of it, I’ll get the ghost to return them to their proper owners—on a condition.”

“What is the condition?”

“Wait. Don’t go off half cocked.”

“What is the condition?”

“I’ll return the diamonds, I’ll forget, as long as I live, that I ever saw Nan Nightingale in my life—provided[62] you’ll go away from here and forget that such a person as Jimmy Duryea ever existed.”

For a moment the detective stared at Jimmy; then he laughed shortly.

“Have you so small an opinion of me as that, Duryea?” he asked. “Do you suppose that I would permit a man like you to ruin the life of that girl, as you would do, if she became your wife?”

“I wouldn’t ruin it; I would make her happy. I would——”

“That’s enough of that. Do you know, I have more than half a notion to call your bluff about your being able to prove yourself to be a Dinwiddie, and take you in right now?”

“Try it on, if you think it will work, Carter.”

Nick started to his feet as if he intended to do so. He was more than half inclined to do it, and probably might have done so, had it not been that at that moment he heard voices, as if persons were approaching the summerhouse.

He stepped quickly to the vine-shaded doorway, and looked out.

The storm had passed, and halfway across the lawn from the house, coming toward him, was Lenore Remsen, accompanied by two of the young women guests at the mansion.

Nick realized instantly that this was no time for the dénouement.

One glance, and the thought that accompanied it, satisfied him that the time was not yet ripe, and he wheeled and returned quickly to the side of Duryea.

Then, without a word, he quickly unlocked the manacles and removed them, dropping them into a pocket out of sight.

“Thanks. Thanks, awfully,” drawled Duryea, and yawned. “You’re really quite a bore, Carter—sometimes.”

“People are coming, Jimmy,” said Nick, speaking rapidly. “You are free, now, for the moment, but it won’t be for long. I am not sparing you, just now; I am sparing that poor girl, whom you are deceiving. But I’ll tell you right now, Duryea, that from this moment, no matter what happens, I do not leave your trail until you are behind the bars of a prison, condemned under the name that belongs to you. I’ll add that the offer I made a little while ago, to let you escape on conditions, is withdrawn. That’s all. You have defied me, Duryea, and you will have to take the consequences. Maybe you know what that means when I say it. If you do not, there are people up at Sing Sing who could tell you.”

The first tinge of uneasiness that Duryea had shown,[64] appeared in his face for an instant; and then the summerhouse door was darkened by the young women whom Nick had seen approaching, and he started to his feet with a smile and an exclamation of greeting. A moment later they were all walking together toward the mansion.

CHAPTER VII.

WHEN A MAN IS DESPERATE.

During what remained of that day, through the dinner hour, and in the evening when the entire company of guests thronged the big rooms, Nick Carter and Duryea kept as far apart as they conveniently could. Nick had an object in carrying out his part of that unspoken arrangement: He wished Jimmy to understand that he had not yet decided what to do.

It has always been one of the detective’s theories that if you leave a criminal well enough alone, he will presently become uneasy under the restraint of inaction, and do something himself. Nick had a notion that Jimmy would attempt some sort of move before another day came around, if only he were left severely to himself; that is, as far as the detective was concerned.

But Nick found an opportunity to make Chick thoroughly acquainted with all that had happened; and he also had it arranged to take Nan in to dinner, and so secured an opportunity to talk with her.

He noticed, while at the dinner table, that Jimmy, who was seated nearly opposite, kept a furtive eye upon him and Nan, and noted that they were whispering together.[66] No doubt the cracksman would think that they were hatching some sort of a plot against him. That was precisely what Nick wished to have him think.

Nick did not believe that Jimmy would have the pluck to hold his ground, and really attempt to marry the girl; for he must know that Nick Carter would never permit that.

No, it was plain to the detective that the bluff on Jimmy’s part was directed at some other effort, since that one must now be abandoned.

There was a time after dinner when Nick and Nan found themselves alone together, at a corner of the veranda. Nick was seated upon the rail, and Nan stood beside him, picking apart the leaves of a wilted rose that she held in her hand.