This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

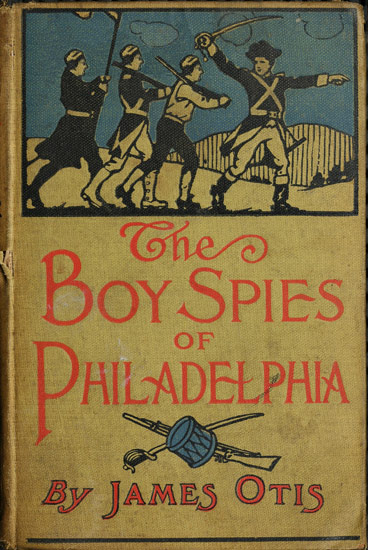

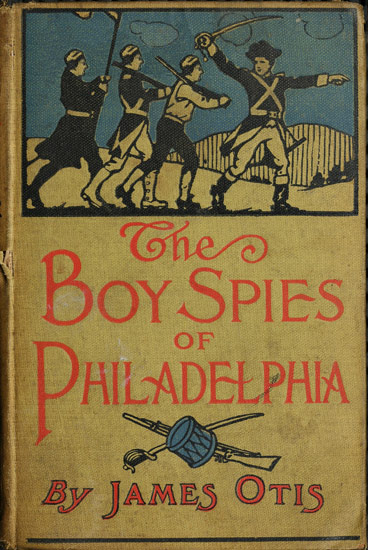

Title: The Boy Spies of Philadelphia

The Story of How the Young Spies Helped the Continental Army at Valley Forge

Author: James Otis

Release Date: January 21, 2014 [eBook #44724]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BOY SPIES OF PHILADELPHIA***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/boyspiesofphilad00otis |

"YOU SEEM TO BE AFRAID A FELLOW WILL GET AWAY," SETH SAID BITTERLY.

The Story of how the Young Spies helped

the Continental Army at

Valley Forge

By JAMES OTIS

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

Copyright 1897

By A. L. Burt

Under the Title of With Washington at Monmouth

THE BOY SPIES OF PHILADELPHIA

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| A "Market-Stopper." | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Under Arrest | 17 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| In Sore Distress | 33 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| A Bold Scheme | 49 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Patrol | 65 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Released | 81 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| On the Alert | 98 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Barren Hill | 113 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Robert Greene | 129 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Conciliatory Bills | 144 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| A Recognition | 160 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Important Information | 176 |

| [iv] | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Evacuation | 192 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Lord Gordon | 208 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| On Special Duty | 223 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Tory Hospitality | 240 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| In Self-Defense | 256 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Preparing for Action | 272 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| A Friendly Warning | 287 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| The Victors | 305 |

The Boy Spies

Of Philadelphia

On the morning of April 2, 1778, three boys, the eldest of whom was not more than sixteen years of age and the youngest hardly a year his junior, were standing on that side of the town-house nearest the pillory, in the city of Philadelphia.

They were not engaged in sportive conversation, nor occupied with schemes for pleasure, as is usually the case with boys of such age; but wore a graver look than seemed suitable to youth under ordinary circumstances.

These boys were witnessing and taking part in events decidedly startling—events well calculated to impress themselves upon the minds even of children.

It is hardly necessary, because such fact is familiar to all Americans, to say that on the 26th of September, 1777, General Howe took possession of the city of Philadelphia, and it was yet occupied by the British forces on this 2d day of April, 1778.

The past winter had been one of gayety for the [2] wealthy Tory inhabitants of the city, since the English officers were pleased to spend their time in every form of revelry, and ever ready to accept the more than generous hospitality which was extended by such of the citizens as were desirous of remaining under British rule.

The officers of the army indulged to the utmost their love for luxury and ease while serving in the command of the indolent Howe, and the privates had so far followed the example set by their superiors that the king's troops had become more demoralized by this winter of idleness than could have been possible under almost any other circumstances.

So great was this demoralization that Benjamin Franklin was able to say with truth, when taunted with the fact that the enemy had captured the city:

"General Howe has not taken Philadelphia; Philadelphia has taken General Howe."

It was at about the time of which this story treats that the British government decided to give command of the forces under General Howe to Sir Henry Clinton, and those of the population loyal to the cause of freedom were considerably exercised in mind as to how this change of officers might effect them.

The three boys, who have as yet hardly been introduced, were by no means prominent in the cause of freedom; in fact they had but just arrived at an age when they began to realize their responsibilities, [3] and as yet had been powerless to perform any great deed in behalf of the cause.

The eldest was Jacob Ludwick, son of that Christopher Ludwick, baker of Germantown, who, having amassed considerable property before the beginning of the struggle for freedom, gave one entire half of it for the cause, and swore at the same time never to shave until the United States were free and independent.

As is known, Washington made him baker-general of the army; but as yet young Jacob had never been able to gain his father's consent to his enlisting.

The second of the trio in point of age was Seth Graydon, son of that Widow Graydon who kept a boarding-house in Drinker's Alley, which had been largely patronized during the winter by officers of the Forty-second Highland and the Royal Irish regiments.

The third was Enoch Ball, also the son of a widow, and his mother it was who had for several years taught French and dancing in her home on Letitia Street.

These three boys had grown old beyond their years during the past winter.

They had witnessed, and more particularly in the case of Seth Graydon, the revelry of the officers who had come to whip into submission the struggling patriots, and well knew to what desperate straits, even for the common necessities of life, were driven the families of those men who had enlisted in the American army. [4]

They saw the invading foe and their sympathizers enjoying every luxury of the table, while hundreds of the poorer classes were literally starving.

Those loyal to the American cause had suffered severely from lack of food and fuel, and were now questioning as to whether, under this newly appointed commander, they would not be called upon to bear yet greater troubles.

Neither of these three lads had ever been hungrier than boys of their age usually are at all times; yet they realized what suffering might come, if, as had been rumored, Sir Henry Clinton was an officer who believed harsh measures necessary when dealing with "rebels."

"There's no doubt about the order having been given," Seth said in reply to a question from one of his companions. "The officers were discussing it last evening, and seemed to think, as they always do, that I can work them no harm through learning their secrets. The time shall come, however, if they stay here much longer, when I will prove that even a boy can be of service to his country."

"But what is the order?" Enoch Ball asked impatiently.

"The entire army is to be in readiness, with three days' rations, to start at a moment's warning on some maneuver which will be executed between now and the fifth of this month."

"Do you suppose General Howe intends to march to Valley Forge?" Jacob asked, with no slight show of anxiety as he thought that his father might be in danger. [5]

"That cannot be. Since the British took possession of Philadelphia there have been many better opportunities for them to fall upon General Washington and his command than now, and it is not likely the enemy would have remained idle all winter waiting to strike a blow after our friends were prepared for it."

"But are they prepared for it?" Jacob asked.

"So I heard Lord Gordon say last night. He declared that, thanks to the instructions of the Baron de Steuben, the American troops were never in better condition, so far as discipline is concerned, than they are at present, and now that the sufferings caused by the severe winter have come to an end, they are in good spirits."

"But if the command is to be taken from General Howe, why is he getting ready for any movement?"

"If I could answer that question, Enoch, I might be able to give even General Washington information for which he would thank me."

"Do you know why General Howe is to be removed from his command?"

"I have heard the British officers say he was severely censured by Parliament for his blunder in causing the disaster to Burgoyne's army by going to the Chesapeake as he did. It seems that he has asked permission to go home, and that is why Sir Henry Clinton has been given the command."

"This maneuver to be executed before the fifth may be one which has been ordered in advance by Clinton," Jacob suggested. [6]

"If such had been the case, the officers who were discussing the matter would have said so."

"Whether it be the one or the other, I do not understand how we can be benefited by having the information. Why did you say that at last we had work to do?"

"For this reason, Enoch Ball: We are now old enough to be of some service to the cause. Jacob's father refuses to allow him to enlist. Mother insists I must remain at home while the British are in possession of the city, and that is also the reason why you are not already a soldier. Now even though we are not in the army, it may be possible for us to aid our friends, and surely nothing at this time can be more important than making them acquainted with the fact that the Britishers are getting ready for some important movement."

"But how can we let them know?" Enoch asked with considerable show of trepidation, for it was not yet two weeks since he had seen a man flogged with an hundred lashes because of its being suspected that his intention was to enter the American lines.

"It is not impossible for one of us to find an officer within a few miles of the town who would forward the information. I believe I know where General Reed and General Cadwalader are, or, at least, how to reach them."

"Would you attempt to leave the city on such an errand?"

"I would, and will." [7]

"And you expect us to go with you?" Enoch continued, showing yet greater signs of fear.

"Not unless you choose."

"Two can do the work as well as three," Jacob interrupted. "If you and I go, Seth, there is no reason why Enoch need be afraid, for we shan't need him."

"But do you think I would let you make an attempt to aid the cause, and not be with you?"

"You are frightened now at the very thought of it," Jacob replied scornfully.

"Yes; and if I am, what then? I may be afraid, for it was terrible to see that poor man's back cut with the lash; but yet I should go if you went."

"Now you are showing yourself to be brave, Enoch," Seth said approvingly, but before he could finish the sentence a shouting, yelling mob turned from High Street[A] into Second, and the boys darted forward to learn the cause of the commotion.

"They have captured another market-stopper," Jacob said a moment later as they neared the noisy throng.

The term he used was one given by the British to those Americans stationed near the city to prevent such farmers as had no scruples against selling provisions to the enemy from disposing of their wares save to those who favored the cause.

During the winter just passed General Howe had attempted to do little more than keep the roads open [8] in order that the country people might come in with their marketing, and severe was the punishment he caused to be meted out to those who would thus attempt to shut off the supplies.

"It is the farmers themselves who should be whipped!" Jacob cried indignantly. "They care not how much aid is given to the enemy so that money comes into their pockets, and the freedom of their country is as nothing compared with the price at which eggs, butter or potatoes can be sold."

"It is better to keep a quiet tongue, Jacob Ludwick," Seth whispered. "There are too many redcoats for us in the crowd, and if one of them should hear your words, that soldier would not be the only one pilloried this day."

"I do not care to fall into their clutches, and therefore I remain silent while good patriots like this light-horseman are being abused; but if it ever happens that the odds are more nearly even I shall say for once to a redcoat what is in my mind."

"And get a flogging for your pains, without having done any one good?"

"As to whether I am whipped depends upon how well the Britisher can fight, while I'm certain great good will be done me by the opportunity to use my tongue as I please."

"Don't talk so loud," Enoch whispered impatiently. "We shall all find ourselves in the jail or on the pillory unless you are careful."

It was quite time Jacob put a bridle on his tongue; the throng of idlers and soldiers who were [9] amusing themselves by pelting the light-horseman with stale eggs, decaying vegetables, or other filth, had now approached so near the boys that words even less loudly spoken could have been overheard.

The prisoner made no effort to protect himself from the unsavory shower; he probably realized that any attempt to do so would only result in his being used more roughly, and did his best to appear unconcerned.

"Do not stay here while he is being whipped," Seth whispered. "What we saw this day a week ago was more than enough for me, and I hope I'll never witness another flogging."

"Wait awhile," and Jacob went nearer the prisoner. "I do not think this one is to be served in that way. See! they are going to put him on the pillory, and by stopping here until the beasts are weary of abusing a helpless man we may be able to render him some assistance."

Seth no longer insisted on leaving the place; the thought had come into his mind that this soldier could tell him where the information he believed the Americans should have would be the most valuable, and it was not improbable they might have an opportunity to talk with him privately.

During half an hour after the prisoner had been placed in the pillory the mob jeered, hooted and pelted him with missiles of every description, and then, one by one, tiring of the inhuman sport, they left the yard for fresh amusement, until the three boys and the horseman were alone, save for the [10] curious ones who, passing by on the street, stopped a moment to look at the soldier.

"It will not always be allowed that the men who are fighting for our liberties can be treated like this in Philadelphia," Seth said in a cautious tone as he stepped so near the pillory that those at the entrance of the yard could not overhear the words.

"Are you a friend?" the prisoner asked with some show of surprise. "I had begun to think there were none left in this town since Howe has made so brave a show, while we at Valley Forge have been starving."

"There are as many friends to the cause in the city as before the Britishers came; but it can do no good for that fact to be known while we are powerless to act."

"You are old enough to serve in the ranks, and should be there, if you would aid the cause."

"So we shall be in good time, friend; but it is not all who are the most willing that can do as they choose. This boy," and Seth pulled Jacob forward, "is the son of Ludwick the baker, of whom you must have heard."

"Heard, lad? Why I know Chris Ludwick as well as I know myself! Do you tell me that he won't allow his son to enlist?"

"He has promised to give his consent this spring, and when Jacob signs the rolls Enoch and I will go with him."

"Then you will have done only that which is your duty. If General Washington could have as many [11] men as he needs, this war would soon be ended, with the United States free and independent."

"We shall do our share," Seth replied, speaking more hurriedly lest those who had captured the prisoner should put an end to the interview before he had accomplished his purpose. "If you believe us to be friends, tell me where we can find an officer of the American army?"

"I have heard you say you were friends; but even if I was able to answer your question I should hesitate about giving any information until I had better surety of your purpose than words which might be spoken by any one."

"Then you shall know why I asked, and after that say if we may be trusted. My mother keeps a boarding-house, and among her guests are several British officers; last night I heard them talking about an order which has just been issued, to the effect that a large portion of the army is to be ready to move at a moment's warning. From what they said, it seems certain some important move is to be made before the fifth of the month."

"Why are you so certain as to the date?" the man asked after a brief pause, during which he appeared to be settling some question in his own mind.

"It was so said by the officers."

"And you have no idea of what may be on foot?"

"I know nothing, except as I have told you. Those who were talking appeared to be ignorant of what it meant." [12]

The prisoner remained silent several moments, and then said in a whisper:

"I shall trust you, lads, for it seems necessary the information should be known at headquarters. If you are deceiving me, you must always remember it as a scurvy trick, and one not worthy even a Tory."

"But we are not deceiving you, nor are we Tories. You know what would be the penalty if we were discovered trying to send information to the Continental army, and yet we are willing to take all the risks, if thereby we can aid our friends."

"That you can, lad, if it so be what you have heard is true. Will you be able to leave town at once?"

"Within an hour."

"Very well, you cannot go too soon. If you travel six miles on the Delaware Road I'll answer for it that you meet some of our friends who will conduct you to those whom you wish to see. Don't tell your story to any officer lower in rank than a colonel, and do not be surprised if those whom you meet give rough usage at first. Hold both your tongue and your temper until the purpose has been accomplished, and then I warrant you will be well thanked for the service."

"We will go at once," Jacob said decidedly. "Is there anything we can do for you, friend?"

"What I most want is to get my neck and wrists out of this contrivance, and that is exactly what you can't help me in the doing. I suppose I should be thankful for being let off so lightly." [13]

"Indeed you should!" Enoch replied quickly. "The Britishers have been flogging the market-stoppers, and that punishment is truly terrible."

"I have seen those who had a taste of it," the prisoner said grimly, "and have no desire to take a dose. But do not stand here talking with me when you have valuable information to give our friends. When you meet with soldiers of our army, say that Ezra Grimshaw sent you to speak with Colonel Powers."

"Is your name Grimshaw?" Enoch asked.

"Yes, lad. If you can get speech with Colonel Powers you need have no fear of rough treatment. Now set out, for time may be precious. Which of you is to do the work?"

"All," Enoch replied quickly, as if fearing that, because of the timidity he had displayed, his friends might deprive him of the opportunity to do his share.

"There is no need of but one," Grimshaw said decidedly, "and many reasons why three should not make the venture, chiefest of which is, that so many might attract the attention of the enemy's patrol, while a single boy on the road would pass unchallenged."

"It is not right one should have all the honor, while the others are deprived of their share," Enoch replied decidedly.

"Lad, is it honor for yourself or the good of the country you have most at heart?" Grimshaw asked sternly. [14]

"I want to be known as one who did not remain idle when he was needed."

"If you really desire to do good to the cause, decide among yourselves as to who shall go, and then let the other two aid him all they can. Do not spend the time in squabbling, but set about the business without delay."

There was no opportunity for him to say more; at that moment a party of British officers entered the yard, evidently bent on amusing themselves by making sport of the prisoner, and the boys were forced to step aside.

Seth beckoned for his comrades to follow him, and not until he was on High Street did he speak. Then it was to say:

"Grimshaw was right; we must not quarrel as to who shall go, but settle the matter at once. Of course each one wants—"

"I should have the chance," Jacob said decidedly. "Either of you may have some trouble to get away; but it is not so with me. My aunt will not worry if I am absent a week; she knows I—"

"Either Enoch or I would have permission to leave home if we explained the reason for going, and, therefore, are as much entitled to the position of messenger as you," Seth interrupted.

"Then how shall it be decided?"

"We will draw lots. Here is a straw; will you hold it, Jacob?"

"Not I, for I want the chance to make my choice." [15]

"Then I will do it," and Seth turned his back to his companions an instant, saying, as he faced them once more, "I have broken the straw into one long and two short pieces. He who draws the longest shall start at once."

Jacob insisted on making his choice first, arguing that such advantage should be his because he was the eldest, and, after considerable study, drew one of the fragments from Seth's hand.

It was so short that he knew the position of messenger was not for him, and stepped back with an expression of bitter disappointment on his face.

Enoch was no more successful, and Seth said triumphantly, as he held up the piece remaining in in his hand:

"It is for me! If you two will tell mother where I've gone I'll start at once."

"That part of the work shall be done properly," Jacob replied, all traces of ill-humor vanishing from his face. "If she allows it, I'll take your place till you get back."

"Mother will be glad to have you there. Try to hear all the officers talk about; but do not let it appear that you are listening."

"Don't fear for me. Shall we walk a mile or so with you?"

"It would do no good, and might not be safe. Tell mother I shall be back to-night, or early to-morrow morning, for I don't intend to let the grass grow under my feet."

"Keep out of the Britishers' way, or we may [16] have to go down to the town-house in order to see you again," Enoch said with a furtive hand-clasp as the three separated, two to go to Drinker's Alley, and the third to render to the cause what service was in his power. [17]

There was no doubt in Seth's mind but that it would be comparatively easy to perform the mission which he had taken upon himself.

He believed the only difficulty to overcome would be that of finding Colonel Powers, or an officer equal or superior to him in rank.

So far as making an excursion on the Delaware Road was concerned, it seemed an exceedingly simple matter, and Seth thought, as he set off at his best pace, that it was possible a fellow could aid the cause very materially without being called upon to endure much suffering, or to perform any severe work.

He met several of the country people coming into the city with poultry, eggs or butter, they being quick to take advantage of the fact that the road had been lately cleared of market-stoppers by the raid which resulted in making of Ezra Grimshaw a prisoner.

During the first half-hour of his journey he fancied that every person he met looked at him scrutinizingly, as if suspicious because he had left the city; but this sensation soon wore away as the [18] time passed and no one molested him, after which he really began to enjoy this impromptu excursion.

When an hour had passed, during which time Seth walked at his best pace, he decided he was at least four miles from the town, and the likelihood of being stopped by the British patrol no longer seemed probable.

Grimshaw had told him if he traveled six miles in this direction he would meet with detachments of Americans, and he believed he was now in that portion of the country where his mission should be successfully ended.

There had not come into his mind the possibility that he could by any chance be considered a suspicious character by those whom he would aid, and he thought that it had been an excess of precaution to send word regarding the journey to his mother.

"I shall be back by the time Jacob and Enoch have had a chance to tell the story," he muttered, "and it would have been as well if I hadn't allowed mother an opportunity to worry about me. General Howe must have little fear of those whom he calls rebels if he allows people to leave the city as readily as I have done."

Twenty minutes later he was made glad by the sight of half a dozen horsemen on the road in advance of him, for he felt positive they were none other than those whom he wished to meet.

Now it was no longer necessary he should press forward rapidly in order to accomplish his purpose, [19] for the mounted party came toward him at full speed.

"Where are you from, lad?" the leader asked as he drew rein directly in front of Seth.

"From the town," the young patriot replied readily, positive of receiving a friendly greeting as soon as his errand was made known. "I want to see Colonel Powers. Ezra Grimshaw told me I would find him hereabouts."

"Where did you see Grimshaw?" the horseman asked more sternly than Seth thought necessary.

"On the pillory. He was captured by the Britishers somewhere out—"

"Yes, we know all about that," the man interrupted, "but Grimshaw would never have told anybody where we might be found."

"But he did," Seth replied stoutly, "and it was under his advice that I came out here to see Colonel Powers."

It seemed strange that this statement should be questioned, yet the young messenger was quite certain from the expression on the faces of the horsemen that such was the case, and as they glanced at each other suspiciously and incredulously, he hastened to add:

"I have information which should be made known to the leaders of the Continental army, and Grimshaw told me to come here and repeat it to Colonel Powers."

"You have information?" the leader asked sharply. "And who may you be, sir?" [20]

"Seth Graydon."

"Are you the son of that widow Graydon who keeps the boarding-house for English officers?"

"Yes," Seth replied without hesitation. "I heard—"

"How did you get speech with Grimshaw if he was on the pillory?" one of the men asked abruptly.

"I, with two friends, was near the town-house when those who made the capture brought him in, and by waiting until the curious ones had gone away it was not difficult to speak with him privately."

"Was he flogged?" the leader asked.

"No, sir."

"Nor treated more severely than being put on the pillory?"

"No, sir."

"And yet he told where we could be found?"

"Yes, because he was eager one of us should have speech with Colonel Powers."

"If the British officers who board with your mother have sent you on this errand they will be disappointed at the result of their scheme. The Tories of Philadelphia are not giving out valuable information to those who are faithful to the cause."

The leader spoke so sternly that for the first time since he parted with his comrades Seth began to feel uncomfortable in mind.

"But I am not a Tory!" he cried stoutly.

"Then you have not taken due advantage of your surroundings," the officer said with a laugh. "A [21] great hulking lad like you would be in the Continental army if he had any love for the cause, instead of playing the spy for the sake of British gold."

"But I am not playing the spy," and now Seth began to grow angry. "I came out here to render you a service, at the risk of being flogged if it is known that I left the city for such a purpose. I intend to enlist as soon as the Britishers have left Philadelphia."

"Indeed? Is that true, my lad? You will enlist when we are on the winning side, and not before, eh?"

"Can I see Colonel Powers?" Seth asked hotly. "Or will you take me to some one equal in rank with him?"

"You shall have an opportunity of seeing an officer in the Continental army, don't fear as to that; but if you count on going back to Philadelphia in time to give valuable information to the Britishers, you are mistaken. They will look for their spy quite a spell before seeing him."

"I tell you I am not a spy!" Seth interrupted.

"That you shall have an opportunity to prove. Have you any weapons?"

"Indeed I haven't."

"Look him over, Hubbard, and make certain he isn't telling more lies," the leader said to one of his followers, and the man dismounted at once, searching Seth's person so roughly that the boy forgot Grimshaw's warning to control his temper. [22]

"You shall be made sorry for this!" he cried hotly. "You shall learn—"

A blow on the side of the head caused him to reel, and he would have fallen but that he staggered against one of the horses.

"Howe's Tory brood grow bold, thinking their master as powerful as he would make it seem," the leader said with a laugh, and added in a threatening tone to Seth, "March ahead of us, young man! Don't make the mistake of thinking you can give us the slip! Your desire to see an officer in the Continental army shall speedily be gratified."

"If this is the way you treat those who would do you a service, it is little wonder you fail to receive much valuable information!" the boy cried angrily.

"Keep your tongue between your teeth, and march on! Any further insolence, and you shall be made to understand that Howe is not the only person who can order floggings administered. Forward, men, and shoot the Tory spawn if he makes any attempt to escape."

Seth recognized the fact that it would be worse than useless to resist, and obeyed sullenly.

At that moment he was very nearly a Tory at heart, for such treatment seemed brutal in the extreme after he had ventured so much in the hope of being of service to his country.

"If this is the way those who would aid the cause are received I don't wonder General Washington finds it difficult to raise recruits," Seth said to himself. "When I have told Jacob [23] and Enoch of my reception by those whom we called friends there will be three who won't enlist as was intended."

It seemed to the boy as if there was no excuse for his thus being made a prisoner, and he felt only bitterness toward those who, an hour previous, he would have been proud to assist.

The troopers kept him moving at his best pace, urging him in front of the horses with their naked swords, hesitating not to prick him roughly now and then when he lagged, until two miles or more had been traversed, when they arrived at what was little more than a trail through the woods, leading from the main road, and here he was ordered to wheel to the right.

Just for an instant he was tempted to make one effort at escaping; but, fortunately, he realized the futility of such a move, and went swiftly up the path as he had been commanded.

Twenty minutes later, when he was nearly breathless owing to the rapid march, the party had arrived at what was evidently a rendezvous for the American patrols.

It was an open space in the midst of dense woods, and here a dozen or more horses were tethered to the trees, while as many men were lounging about in a most indolent fashion.

"What have you got there, Jordan?" one of the idlers cried, and the leader replied with a coarse laugh: [24]

"A young Tory who is trying to win his spurs in a most bungling fashion."

"From the town?"

"He is the son of the woman who runs a boarding-house for British officers, and claims to have been sent by Grimshaw."

"Where is Grimshaw?"

"On the pillory, so the boy says. He was captured this morning by some of the Queen's Rangers."

"He is like to have a sore back when he shows up here again."

"We will send them one in return," Captain Jordan replied, pointing to Seth. "It won't be a bad idea to show Howe that we can swing the whip as well as his redcoats, and if ever a cub deserved a flogging it is this one."

"We've got nothing else to do, so let's try our hand on him," some one cried, and Seth looked around terrified.

If these men decided to treat him as a Tory he would be powerless against them, and there seemed little chance he could convince the troopers of the truth of his statement.

Two of the soldiers began cutting birchen switches, as if believing the suggestion would be carried into effect immediately, and Seth's face grew very white.

"We'll dress him down to your liking captain, if you give the word," one of the men who had begun the preparations for the punishment cried, as [25] if eager to be at the work. "It's time we commenced to show the Britishers that the floggings are not to be all on one side."

Captain Jordan, although the first to make such a suggestion, was not prepared to give the order, knowing full well that he would be exceeding his authority should he do so, and replied with a laugh:

"We shan't lose anything by waiting, so there's no need of being in a hurry. Look out for the prisoner, Hubbard, and see to it that he don't escape you."

The trooper thus commanded seized Seth roughly by the shoulder, and half-dragging, half-leading him to a tree on one side of the clearing, proceeded to fetter the boy by tying him securely.

"You seem to be afraid a fellow will get away," Seth said bitterly. "Fifteen or twenty men should be enough to guard one boy."

"Very likely they are, lad; but we don't intend to give ourselves any more trouble than is necessary. You will stay here, I reckon, and we shan't be put to the bother of watching you."

There was something in the man's tone which caused Seth to believe he might be made a friend.

By this time he realized it was worse than useless for him to display temper, and that it might yet be possible to escape the threatened punishment. Therefore he said in a conciliatory tone:

"Does it seem so strange to you, my wish to be of benefit to the cause, that you cannot believe my [26] story sufficiently to allow me an interview with Colonel Powers?"

"I don't see where the harm would be in that, lad; but it isn't for me to say. Captain Jordan is in command of this squad."

"But hark you, Mr. Hubbard. I have told only the truth. If my mother, a poor widow woman, is forced to take English officers as boarders, does that make of me a Tory?"

"Well, lad, I can't rightly say it does, though after the junketin's you people have had in Philadelphia this winter, I allow all hands are more or less afflicted with that disease."

"But I am not. The story I told about meeting Grimshaw is true. One of my companions is the son of Chris Ludwick, whom likely you know; we drew lots to see who should come here, and I was pleased because the choice fell on me. Do you think it right that I should be flogged and sent back before your officers have had time to find out whether I am telling the truth or a lie?"

"No, lad, I don't, for I allow you have had plenty of chances to hear that which would be valuable to our side; but whether you would tell it or not is another matter."

"Why shouldn't I want to tell it? Are the soldiers of the Continental army the only men in the country who love the cause?"

"Those who love the cause should be in the army when men are needed as now."

"Before General Howe took possession of Philadelphia [27] I was too young to be received as a soldier—am too young now; but shall make the attempt to enter as soon as possible."

"Would you be willing to enlist to-day?"

"Not until I have talked with my mother. She depends upon me for assistance, and it isn't right I should leave home without her permission. But that has nothing to do with the story I came to tell. I swear to you I have heard that which should be known to your officers. I told it to Grimshaw, and he insisted I should not repeat it to any one of lower rank than a colonel."

"Then it must be mighty important information."

"So it is; yet without giving me an opportunity to tell it I am to be kept here and flogged."

"That is Captain Jordan's affair," Hubbard replied; but Seth understood that his words had had some effect upon the man, and he continued yet more earnestly:

"There can be no harm in taking me to Colonel Powers, for after that has been done you will still have the opportunity to give me a flogging. When I have repeated that which I came to say I shall yet be a prisoner."

Hubbard made no reply to this, but walked quickly away to where Jordan was talking with a group of the men, and Seth began to hope he could yet accomplish his purpose, although he was far from feeling comfortable in mind as to what might be the final result of his attempt to aid the cause. [28]

During the next half-hour no one came sufficiently near the prisoner to admit of his entering into another conversation.

The men were discussing some matter very earnestly, and Seth believed he himself was the subject.

Then the scene was changed.

Ten or twelve horsemen rode into the open, and by their uniforms Seth understood that officers of a higher rank than Captain Jordan had arrived.

The newcomers did not dismount, but received the captain's report while in the saddle, and then, to the prisoner's great delight, rode directly toward him.

"What is your name?" the eldest member of the party asked.

"Seth Graydon."

"Is it true that your mother has as boarders many officers of the British army?"

"Yes, sir. There are seven from the Forty-second Highlanders, five of the Royal Irish regiment, and Lord Cosmo Gordon."

"And you overheard a conversation at your mother's house which you believed would be of value to us?"

"Yes, sir," and Seth told in detail of his conversation with Ezra Grimshaw, concluding by asking, "Are you Colonel Powers?"

"I am, my lad, and see no reason for doubting your good intentions. You have been roughly treated, it is true; but it has not been serious, and you must realize that the soldiers are suspicious [29] because of the many attempts at treachery this spring. You say you told Grimshaw what you had heard? Did he insist you should repeat it to me in private?"

"No, sir. I was simply to tell no one of lower rank."

"Then what have you to say?"

Seth detailed the conversation he had heard in his mother's house, and Colonel Powers questioned him closely regarding the comments which had been made by the British officers at the time the subject was under discussion.

When he had answered these questions to the best of his ability, the colonel beckoned for Captain Jordan, and said harshly:

"I wonder, captain, that you and your troops should be so afraid of one boy as to bind him in such a manner. He has brought most valuable information, and should be richly rewarded for his services, instead of being trussed up in this fashion."

The captain looked confused as he released Seth, and while doing so whispered in the boy's ear:

"I am sorry, lad, for what has happened, and that is all any man can say."

However much ill-will Seth may have felt toward his captor just at that moment, he had no desire to show it.

The words of commendation spoken by Colonel Powers were sufficient reward for all he had undergone during his time of arrest, and he felt almost friendly-disposed, even toward those of the troopers [30] who had so eagerly begun to prepare the switches for his back.

"You shall have an escort as far toward the town as is consistent with your safety and ours," the colonel said when Seth was freed from the ropes. "I thank you for your service, and shall, perhaps, at some time be able to reward you better. When you decide to enlist, come to me."

Then the colonel, beckoning to his staff, rode away with the air of one who has an important duty to execute, and Captain Jordan held out his hand to his late prisoner.

"Forgive me, lad, and say you bear me no ill-will."

"That I can readily do, now my message has been delivered," Seth replied promptly, and the troopers gathered around, each as eager to show his friendliness as he previously had been to inflict punishment.

A horse was brought up, and the captain, now the most friendly of soldiers, said to Seth:

"We'll escort you as far as the creek; further than that is hardly safe. You can easily reach home before dark, for the ride will not be a long one."

"I can walk as well as not, if you have other work to do," Seth replied.

"We are stationed on the road here to stop the country people from carrying in produce, and by giving you a lift shall only be continuing our duties." [31]

Seth mounted; the captain rode by his side; half a dozen men came into line in the rear, and the little party started at a sharp trot, which, owing to his lack of skill as a horseman, effectually prevented Seth from joining in the conversation the captain endeavored to carry on.

In half an hour or less the squad had arrived at the bank of the creek, and Seth dismounted.

"The next time you come this way I'll try to treat you in a better fashion, lad," Captain Jordan said, and Seth replied as the party rode away:

"I don't doubt that; but the next time I come it will be with more caution, fearing lest I meet with those who will be quicker to give me the Tory's portion than were you."

Then he set out at a rapid pace, congratulating himself his troubles were over, and that he would be at home before any of the inmates of his mother's house should question his prolonged absence.

He believed his mission had been accomplished; that he had rendered no slight service to the cause, and that there was no longer any danger to be apprehended.

He whistled as he walked, giving but little heed to what might be before or behind him, until, within less than five minutes from the time he had parted with the American horsemen, he was confronted by a squad of the Queen's Rangers, commanded by a lieutenant.

"Take him up in front of you," the officer said to the trooper nearest him. "We can't be delayed by forcing him to march on foot." [32]

"What are you to do with me?" Seth cried in surprise, for this command was the first word which had been spoken by either party.

"That remains to be seen," the officer replied curtly.

"But there is no reason for arresting me," Seth continued. "I am the son of Mrs. Graydon, who keeps the boarding-house in Drinker's Alley."

"Ah! Indeed?"

"Certainly I am, and any of the officers who live there can vouch for me."

"Those who vouch for you would be indiscreet," the lieutenant said sharply. "You are under arrest, and it is possible may persuade the commander that Mrs. Graydon's son does not hold communication with the rebels; but any protestations on your part would be useless, so far as we are concerned, for we saw you escorted by a squad of rebel horsemen. Mount in front of the trooper and make no parley. General Howe has a short shrift for spies, and we shall not spend our time here convincing you that your treason has been discovered."

Seth was almost helpless through fear.

Since the Rangers had seen him riding in company with Continental troopers there was little question but that he would be considered a spy, and he knew what would probably be the punishment. [33]

Seth was literally overwhelmed by the misfortune which had come upon him.

After Colonel Powers interposed to prevent the threatened whipping by the American soldiers, he believed his troubles were over, and that he might be made prisoner by the British was a possibility he never contemplated.

It was not necessary any one should explain to him how dangerous was his situation.

The lieutenant and his men had seen him escorted by a body of "rebel" troops in such a manner as to show they were friends, and then he had come directly toward the city, all of which would be sufficient to prove him a spy in these times, when an accusation was almost equivalent to a verdict of guilty.

And poor Seth was well aware what punishment was dealt out to spies. He had seen one man hanged for such an offense, and remained in the house on two other occasions lest he should inadvertently witness some portion of other horrible spectacles.

He knew the evidence against him was sufficient for conviction, and understood that, once sentence [34] had been passed, there was little or no hope for mercy.

It is not strange, nor was it any proof of cowardice, that he was so overcome by the knowledge of his position as to be thoroughly unnerved; and when, on arriving at the outskirts of the town, the lieutenant ordered him to dismount and walk, he was able to do so only after being assisted by a soldier on either side.

Like one in a dream he understood, as they went toward the prison, that all the idlers on the streets followed, hooting and yelling, and once he fancied some person called him by name, but it was as if he could not raise his head to look around.

The only facts he fully realized were that he stood face to face with a shameful death, and that by the rules of war he fully deserved it.

He had been so proud when it was decided by lot that he should carry the information to the Continental army, and believed himself so brave! Now, however, he understood that he was acting as a coward would act, and tried again and again to appear more courageous.

"If my death was to be of great benefit to the cause, it would not seem so hard," he repeated to himself more than once during that disgraceful journey through the streets, while he was being jeered at, as many American soldiers had been, when he was among the rabble, although not of them.

If he was wearing a uniform of buff and blue, he [35] knew that among those who saw him would be many sympathizers; but in civilian's garb he could not be distinguished from some vile criminal, and there would be no glory in what he was called upon to suffer.

The Rangers led him past the town-house, and in the yard, still standing on the pillory, he saw Ezra Grimshaw.

The soldier must have recognized the boy as he passed, but yet he gave no token of recognition, and so sore was Seth's distress that he failed to understand how much more desperate would be his strait if the "market-stopper" had greeted him as a friend.

When the jail-door closed behind him with a sullen clang it sounded in the boy's ears like a knell of doom, and he firmly believed that when he next passed through the portal it would be on his way to the scaffold.

After being heavily ironed he was thrust into a cell so small that he could hardly have stood upright even though the fetters were removed, and there left to the misery of his own thoughts.

During the march through the city he had not raised his head, save while passing the pillory, therefore was ignorant of the fact that Jacob and Enoch had followed him as closely as the soldiers would permit, hoping an opportunity to whisper a cheering word in his ear might present itself.

Even though Seth had not been so bowed down by grief, it is hardly probable his friends would have [36] been allowed to communicate with him; but he might have been cheered by their glances, knowing he was not alone among enemies.

Yet even this poor consolation was denied him, and when the door of the jail finally hid him from view, Enoch and Jacob stood silent and motionless in front of the sinister-looking building, gazing with grief and dismay at each other.

"How do you suppose they caught him?" Enoch asked after a long time of silence, during which Jacob had led him out on to High Street lest their sorrow should be observed by some of the enemy, and they arrested on the charge of having aided the alleged spy.

"We shall most likely hear the story the Rangers tell, for it will soon be known around town, although we shan't be able to say whether it's the truth."

"Do you suppose he found any officer of our army?"

"I think he must have done so. It isn't reasonable to suppose they made him a prisoner simply because he walked out into the country. Besides, I heard one of the Rangers tell a friend that Seth was a spy. Perhaps they captured him just as he was leaving the Continental camp."

"Do you think they will hang him?" and Enoch's voice trembled as he asked the question.

"Yes, if it is proven he's a spy, and the Britishers who made the capture will take good care their stories are strong enough to do that."

"But, Jacob, must we remain quiet while they are [37] killing poor Seth?" and now the big tears were rolling down Enoch's cheeks.

"We shall be forced to, if the matter goes as far as that. We must do what we can before he is put on trial."

"But, what can we do? We have no friends among the Britishers, and even though we had it isn't likely we could prevent General Howe from doing as he pleases!"

"Then you believe we can do nothing?" Jacob said almost despairingly.

"It doesn't seem possible, although I would suffer anything, except death itself, to help him. Oh, Jacob!" Enoch cried as a sudden thought came into his mind. "We must tell his mother where he is, and that will be terrible!"

Jacob made no reply. He believed it unmanly to cry, and the tears were so near his eyelids that he dared not speak lest they should flow as copiously as Enoch's.

The two were walking up High Street, unconscious of the direction in which they were going, when Jacob gave vent to an exclamation of mingled surprise and joy as he cried:

"What a stupid I have been not to think of him! He would be a very pleasant gentleman if he wasn't a Britisher!"

"Whom do you mean?" and Enoch looked around in perplexity.

"There! On the other side of the street, coming this way!" [38]

"I don't see any one except Lord Cosmo Gordon, who lives at Seth's home."

"And that is the very man who will help us if it is possible for him to do anything."

"Do you mean that a Britisher would speak a good word for Seth after it is known he has been carrying information to the Continental army?"

"I'm not so certain about that; but I feel positive if any of the enemy would do a good turn, that one is Lord Gordon. Have you ever seen a more pleasant gentleman?"

"He has always been very kind; but then he did not know we were willing to work against his king."

"Of course he knew it! How many times has he called us young rebels, and declared that when we were ripe for the army he would take good care we did not get the chance to enlist?"

"He was only in sport, and would talk differently if he knew what we have done."

"It can do no harm to try. Seth is likely to be hanged as a spy, and no worse punishment can be given him. I am going to tell Lord Gordon the story. Will you come?"

Enoch hesitated just an instant as the thought came to his mind that by acknowledging their share in what had been done they might be making great trouble for themselves, and then, his better nature asserting itself, he replied:

"I will follow you to do anything that might by chance help poor Seth." [39]

Jacob had hardly waited for him to speak. Lord Gordon was already opposite, walking rapidly past, and unless they overtook him at once he must soon be so far away that an undignified chase would be necessary.

Master Ludwick crossed the street at a run, Enoch following closely behind, and a few seconds later, to his great surprise, Lord Gordon was brought to a standstill as Jacob halted directly in front of him.

"Ah! here are two of my young rebels! Where is the third? I thought you were an inseparable trio."

"I don't know what you mean by that, sir; but we're in most terrible trouble, and you have always been so kind, even though you are a—I mean, you've been so kind that I thought—I mean, I was in hopes you could—you would be willing to—"

"I can well understand that you are now having trouble to talk plainly," Lord Gordon said with a smile. "I gather from the beginning of your incoherent remarks that you have come to me for assistance. The rebels have at last turned to the British for relief!"

"But this is something terrible!" Jacob exclaimed vehemently, and then, after trying unsuccessfully to think of the proper words, he cried, "Seth is going to be hanged!"

"Hanged! You rebels don't go to the gallows so young; in fact evince a decided aversion to anything of the kind. Now take plenty of time, and try to tell me what disturbs you so seriously," Lord [40] Gordon said with a hearty laugh. "I had an engagement at the tavern; but am willing to break it if I can do anything to make good subjects for his majesty of you three boys."

"But this is no laughing matter, sir," Jacob cried, despairing of being able to make the Englishman understand how desperate was the situation. "Seth Graydon has been arrested as a spy, and is in prison at this instant!"

"What?" and now the smile faded from Lord Gordon's face. "Do you mean our Seth—your comrade?"

"Indeed I do, sir!"

"But it is incredible! He hasn't been out of the city, and although I suppose he has hopes of some day entering the American army, as all you young rebels have, he is not in a position where he could play the spy, however much he may be willing to do so."

Jacob looked confused; he was not certain but that he might be injuring his friend's cause by confessing the truth, and yet at the some time it was not reasonable to suppose Lord Gordon could render any assistance unless he understood the entire affair.

"Tell his lordship the whole story," Enoch said in a low tone. "I am certain he would not use it against any of us."

"Yes, my lad, it will be better to tell me the truth. I do not promise to aid you; but I will treat as confidential anything you may say." [41]

The officer's tone was so kindly that Jacob hesitated no longer. He told all he knew regarding the matter, making no attempt to conceal the fact that Seth had listened to the conversation of the guests in his mother's house, and when he concluded Lord Gordon stood silent, like one who is trying to settle some vexed question.

Then he said, as if to himself:

"This will be sad news for his mother, and she is a worthy woman!"

"It will just about kill her!" Enoch cried.

"Did she know he was going to meet the rebels?" and now the officer spoke sternly.

"Indeed she didn't, sir. Enoch and I told her he had gone out on the Delaware Road; but made it appear that we were ignorant as to why he went."

"Why should you not have told the truth?"

"We were afraid she might think it her duty to tell you, because what he learned had been gained—well, perhaps it wouldn't have been just right to take such an advantage except in a case like this, where no fellow could sit still knowing his friends might be running into a trap."

"Don't you think Mrs. Graydon ever carried any information to the American camp?"

"I am sure she never did—not since General Howe has been in this city," Enoch replied promptly.

"Why are you so positive?"

"I've heard her say that if we are willing to take [42] your money, we should at least be true to you for the time being."

"It is quite evident you boys are not of the same opinion."

"We expect to go into the army very soon, and it is our duty to do all we can to aid the cause," Jacob said stoutly.

"And you know, while you are trying to aid the cause, what is to be expected if you are captured?"

Jacob understood that he was not aiding his friend by speaking boldly, and Lord Gordon had so clearly the best of him in the matter that he was wholly at loss for a reply.

"We never believed that by going to where Seth would meet the Continentals anything more could come of it than a flogging, and that seemed terrible enough," Enoch cried. "Seth had no idea he might be arrested as a spy!"

"We won't quibble about the fine points of the case, my lad. It is a fact that he has voluntarily placed himself in a position where he certainly appears as if he had been acting the spy, and there is, perhaps, not an officer in his majesty's army, except myself, who would believe that this is his first wrongdoing."

Jacob was on the point of saying that there could be nothing wrong in aiding one's country, but, fortunately for Seth, he realized in time that Lord Gordon considered the Americans rebels, rather than patriots, and to him anything of the kind would not seem praiseworthy. [43]

"Can't you help him, sir?" Enoch asked imploringly, understanding that nothing could be gained by discussing the matter.

"I am afraid my influence is not sufficient to effect anything while the charge is so serious. There is but one punishment for spies, and it is seldom crimes of that kind are pardoned."

"Then must poor Seth be hanged?"

"I shall do what I can to help him, my lad, of that you may be certain. Possibly we may be able to have a lighter charge brought against him, and to that end I will work. His mother must know he is in prison, but need not be told he is there as a spy. Disagreeable though the task will be, I take it upon myself to acquaint her with some of the reasons for his absence, and also promise to do all in my power to save his life."

"If General Howe will let him off with a flogging, Jacob and I are willing to come up for our share of the punishment as the price of setting Seth free."

"That is a generous offer, Enoch, whether it be a fair one or not. Meet me at the City Tavern to-morrow forenoon at ten o'clock, and I will then let you know what can be done." Both the boys would have thanked the kindly Englishman for the interest he displayed in their comrade, but that he checked their grateful words by saying hurriedly:

"It is exceedingly bad taste to have a scene on the street, boys, therefore we will say no more [44] about it to-day. Perhaps when I see you to-morrow there will be no occasion to thank me, for I really have but little influence with General Howe. Don't show yourself to Mrs. Graydon to-night, for she would soon learn the sad news from the expression on your faces, and, unless it is absolutely necessary, I do not propose that the worthy lady shall know in what sore distress her son is, through his own recklessness."

Then Lord Gordon walked rapidly away, allowing the boys no time to make a reply, and although he had not given them very much encouragement, both felt decidedly relieved because of the interview.

"If he can't help Seth there isn't a Britisher in this city who can," Jacob said with emphasis. "He's the only one I know of who'd even take the trouble to talk with a couple of boys."

"But what are we to do now? I don't feel as if I could go home while poor Seth is in prison, and most likely thinking every minute of the scaffold."

"We can't do him any good by walking around the streets, and I don't want to go out to Germantown, because I might not be able to get back in time to meet Lord Gordon. Suppose I sleep at your mother's house to-night?"

"I'll be glad to have you, and she will make no question. Are we to tell her?"

"I think we shall be obliged to. It may be we can do something to help Seth, and she must know why you are absent from the house, in case it so happens we want to be away." [45]

If Enoch had feared his mother would reproach him for having taken even a passive part in what might lead to Seth's death, he was mistaken. She spoke only of her sympathy for Mrs. Graydon, and the hope that Lord Gordon would aid the unfortunate boy in some way.

"If I was in Seth's place, mother, should you blame me for having tried to aid the cause?"

"No, my son. You are old enough to know your own mind, and should be at liberty to do that which you think right."

"Then you would make no question if I wanted to enlist?"

"That is for you to decide, my boy. Your mother's heart would be very near breaking if you were killed; but her sorrow could be no greater than is borne uncomplainingly by many mothers in this country where brave men are struggling for freedom."

Never had Enoch appreciated his mother's love as he did at this moment, and when he and Jacob bade her good-night both boys kissed her with unusual tenderness.

Fully an hour before the time appointed Jacob and Enoch were at the rendezvous waiting for Lord Gordon.

Many times that morning had they heard comments made upon Seth's arrest, and the opinion of all was to the effect that he would suffer the fate of a spy, whether he was really guilty or not.

"The appearances are against him," a gentleman [46] friend of Enoch's mother said when the story had been told him in the hope he might aid the prisoner in some way. "Those who made the capture say they saw him escorted to the bank of the creek by a squad of Continental troopers, and that he appeared to be on the most friendly terms with them. That is sufficient to prove him a spy, and I question if there is in this city a single person, with the exception of General Howe himself, who could serve him."

Both the boys heard this remark, and were no longer hopeful regarding Lord Gordon's ability to save their comrade, however much he might desire to do so.

The officer was punctual to the appointment he had made, and at once invited them into the coffee-room of the tavern, saying as he did so:

"It is not well we should stand on the street where all may see us, for it may be important that I should not appear to be on friendly terms with you."

When they were where a conversation could be conducted with some degree of privacy the boys waited for their companion to speak, but he remained silent, as if in deep thought, until Enoch asked timidly:

"Will it be possible for your lordship to help poor Seth?"

"I am not certain, my lad, although I hope so. The case is far more serious than I deemed possible yesterday. I believe the story you told; but you [47] could not persuade others it is true, and I have no doubt but that he will be found guilty."

"Does his mother know?" Enoch whispered.

"I thought it best to tell her at least a portion of the story, for she would have heard it from the gossips before this time. I have not concealed from her the fact that he is in a most serious position; but at the same time have allowed the good woman to believe I could effect his release."

"And now you do not think that will be possible?"

Instead of replying to this question Lord Gordon asked suddenly:

"How far would you two boys go in trying to release your comrade?"

"We are ready to take any chances," Jacob replied firmly.

"Does that mean you would imperil your lives in the effort to save his?"

The boys looked at each other in something very like alarm, for Lord Gordon's tone was exceedingly grave, and then Enoch replied in a voice which trembled despite all his efforts to render it steady:

"I am willing and ready to do anything, no matter what, to help Seth."

"So am I," Jacob added emphatically.

While one might have counted twenty Lord Gordon remained silent, looking like a man who is uncertain as to what he ought to do, and then he said quietly:

"Then meet me opposite the town-house at half [48] an hour before midnight. It is only by desperate measures that his life can be saved, and I am ready to aid you in so far as I can without dishonor. It will not be well for us to be seen together, neither are you to visit Mrs. Graydon. Be at the rendezvous promptly, and Seth shall be free by sunrise, or there will no longer remain any hope of aiding him."

Without giving them an opportunity to question him, Lord Gordon walked out of the building, leaving them gazing questioningly into each other's eyes. [49]

The boys were so thoroughly surprised by Lord Gordon's making an appointment with them as hardly to be conscious of what they did immediately after he left the room.

They sat motionless as if in bewilderment, each fancying he had an inkling of his lordship's intentions, and not daring to believe that which was in his mind.

Both must have remained in this condition of stupefaction many moments, for finally one of the attendants came up, tapped Jacob more energetically than politely on the shoulder, and intimated that if he did not wish to be served with anything he could spend his time quite as profitably, so far as the management of the tavern was concerned, in some other place.

Master Ludwick, understanding that he had the right to be in the hostelry, because of having been introduced by one of the landlord's best patrons, and angry at being treated as if he was not a desirable guest, said sharply:

"We are here because Lord Gordon invited us to [50] enter with him, and we shall stay until it seems best to go."

The servant muttered something which was probably intended as an apology, and made no further attempt to drive the boys from the coffee-room; but Enoch did not feel altogether at ease after this incident.

"Let us go, Jacob," he whispered. "As the servant said, this is no place for us, and, besides, we cannot be as private here as I would like while speaking of Lord Gordon's intentions."

"I should have gone before but for that impudent fellow, and now we have stayed so long that it cannot be said we ran away because of his words, I am ready. Where shall we go?"

"Anywhere, so we can be alone."

"To your house?"

"No. If I do not mistake Lord Gordon, there is serious work before us this night, and I would rather not be where mother could question me."

"Why?"

"Because I should betray that which is in my mind when she first began to talk, and if I am correct in putting a meaning on his lordship's words, it is better that no one save ourselves knows what is to be done, lest by the knowing they could be considered as in some way guilty of our acts."

By this time the boys were on the sidewalk in the midst of a group of idle officers and civilians who were commenting upon the news of the day, and the major of the Forty-second Highlanders, who was [51] well known to both Jacob and Enoch because of the fact that he boarded at Seth's home, was speaking sufficiently loud for them to hear his remark as they passed.

"According to the report of the lieutenant of the Rangers, there can be no question but that the little rascal has been in communication with the American forces for a long while, and it is not difficult now to understand how information of our movements reached the rebel officers. Among ourselves at the boarding-house we have talked freely, little thinking a boy, hardly more than fifteen years of age, was playing the spy; but his career will shortly be ended."

"When will he be court-martialed?" the major's companion asked.

"To-morrow afternoon, and probably hanged on the following morning."

"Then you have no doubt as to the result?"

"There can be no doubt, my dear sir. The evidence is so conclusive against him that I see no loophole of escape. All I regret is that he has been allowed to ply his trade as spy so long and so advantageously."

"Come away, Jacob," Enoch whispered, clutching his comrade nervously by the coat-sleeve. "It is fortunate for poor Seth that all the Britishers are not as hard-hearted as the major."

"We should stay long enough to convince him he is telling that which is not true," Master Ludwick replied stoutly; but at the same time obeying the [52] pressure of his friend's hand by moving away from the group.

"It would be difficult to persuade him he was speaking that which is false. You remember Lord Gordon told us he was probably the only person in the British army who would believe our statement in face of the proof against poor Seth."

"Lord Gordon is a man, even though he is a Britisher."

"And I hope the time will come when I can do him as great a service as he is willing to do Seth."

Enoch gave words to this desire simply as a mode of expressing his admiration for the kindly-hearted officer who would forget a quarrel of nations to aid a widow and the fatherless. He little dreamed that before many weeks had passed he would be in a position to do Lord Gordon quite as great a service as that gentleman was evidently about to do for Seth.

The two boys continued on up High Street to Sixth, and then through Walnut to the long shed adjoining the State-house yard, where the Indians who came into town on business were accustomed to take shelter, and there they halted for a consultation, or, rather, to settle in their own minds what his lordship meant when he appointed an interview at midnight near the pillory.

"He despairs of trying to aid Seth through General Howe," Enoch said as if thinking aloud.

"And intends that we shall help him break jail," Jacob added. [53]

"In that case the poor fellow will still be in danger of being hanged, in case the British ever catch him again."

"Very true; but he will be much better off, according to my way of thinking, with a price set upon his head by General Howe, providing he is with the American army, than if he remains here until day after to-morrow, when, as the major says, he will most likely be hanged."

"Of course that is true. I was only thinking that if we succeeded in effecting his release we should not remove the danger from him, so far as the British are concerned."

"I am well satisfied if so much can be done. I wish Lord Gordon had thought it best to give us more of an idea regarding his plans, so we might make our preparations."

"But what could you do if we knew positively that he intends to help Seth escape from jail?"

"Nothing, although it seems as if we would be better able to perform the work if we made some preparations."

"Do you think it will be necessary for us to run away with him?"

"That must be as Lord Gordon says. Your mother knows exactly the condition of affairs, and will understand that we are working in Seth's behalf, in case you should not come home to-night. If you and I accompany him in his flight, I will trust to it that his lordship finds a way to send word to our people without making any trouble for himself. [54] And in case we go we shall be no worse off than a great many others in this country. Remember Judge McKean, who last year was hunted like a fox through the State, forced to move his family five times, and hide them at last in a little log hut in the woods. Knowing what he and his suffered for the cause, we should not complain however hard our lot may be."

"I am not complaining, Jacob. I stand ready to bear anything which falls to my share, if by so doing I can be of service to the cause; but it isn't possible we could ever do as much as Judge McKean, who signed the Declaration of Independence."

"We can at least do our share toward making good the statement which he signed, and as to the future, so that we get Seth out of the Britishers' clutches we won't trouble our heads. It seems to me the most important question now is, what we are to do between this and midnight. We ought not to be seen loitering around the streets."

"Suppose you go down to my home and ask mother to give us as much food as will last us twenty-four hours. We will then go out near the Carpenter mansion, where we can remain hidden in the grove until night. Such of the provisions as we do not eat during the day will suffice for Seth to take with him in his flight."

"That is a good idea, Enoch, and it will be doing something toward preparing for the night's work. Now, where think you will Seth easiest find the [55] American forces? Where he saw them yesterday? Or in the direction of Valley Forge?"

"I think that is a question Lord Gordon himself can best decide, for he will most probably know in which direction it would be safest for Seth to travel. Shall I wait here, or walk part of the way home with you?"

"Stay where you are. I will be back in half an hour."

Mrs. Ball must have suspected that the boys were engaged in some important work, for, like the wise woman she was, she complied with her son's request, asking not so much as a single question, and scanty though her store of provisions was, collected such an amount as would have sufficed to feed two hungry boys at least three days.

Wrapping the collection neatly in a cloth, she placed it in a small bag, saying as she did so:

"It will be easier to carry in this, with not so much chance of wasting it. Tell Enoch that his mother's prayers will follow him until he comes back to her, and say that he is to remember how eagerly she watches for his return."

"I think he'll be back before to-morrow, Mrs. Ball; but if he isn't, don't you worry. There's a certain Britisher in this city who's got a heart under his red coat, and if it happens Enoch is to remain away very long, that same Britisher will send you word."

"God bless you, boys! God bless all of you, and prosper you in your undertaking!" [56]

There was a suspicious moisture in Jacob's eyes as he hurried through Letitia Street to where his comrade was awaiting him; but by the aid of one corner of the bag he succeeded so far in effacing the telltale sign of weakness that no one would have suspected how very near he was to breaking down entirely, simply because of the kindly words spoken by the mistress of the dancing school.

The hours passed slowly and wearily to the two boys who had nothing more to do than spend the time in waiting; but finally the moment came when, in order to keep the appointment, they must leave their retreat in the grove, and it was with a sense of decided relief that they hurried forward, although knowing that they were hastening on a perilous venture.

On arriving at that side of the town-house where stood the pillory, not a person was to be seen.

Fortunately they had met with no one, not even the patrol, during their walk down from Sixth Street, and as they stood behind the instrument of torture whereon Grimshaw had passed so many painful hours it was safe to assume that no person unfriendly to their design was aware of their whereabouts.

Five, ten minutes passed, and yet no sign of life upon the deserted street.

"Something has happened; he cannot come," Enoch whispered nervously.

"I will answer for him," Jacob replied confidently. "He isn't the kind of a man who would [57] back out after promising, and he knows we will wait for him even though he is two hours late."

"If any of the Britishers should see us, we would be put under arrest."

"But there is no danger of that, not while we stay here, and the night is so dark that the redcoats would be obliged to hunt around a good while before finding us. I don't think it is safe to talk, because—here comes some one! Now the question is whether it's the man we are waiting for."

In the gloom the boys could faintly see a dark form coming up the street, and with loudly beating hearts they waited until the figure was nearly opposite, when a low whistle broke the silence, and Enoch said with a long-drawn sigh of relief:

"It is him. No one else would make a signal here."

Then, without waiting for an opinion from his comrade, he stepped out in view, and the newcomer directed his steps toward the pillory.

It was Lord Gordon, and he said, as he approached:

"You have a good hiding-place here, and we'll take advantage of it, because I have a few words to say before we proceed to business." Then, stepping back behind the scaffold, he continued in a low, grave tone: "Unless I was firmly convinced that the story you told me regarding Seth's movements was true, and unless I believed you when you say this is the first time he has ever carried information to the Americans, I should not attempt to aid you. [58] That which I am doing may seem dishonorable to those who do not know all the facts in the case. My own conscience approves, however, and I shall do what, as an officer in the British army, I ought not to do, in order to save from a disgraceful death a boy who has been indiscreet—not guilty as a spy. But although I can thus satisfy my conscience, I could not have my actions known to the commander of the forces without laying myself open—and justly—to a charge of treason. Therefore I ask that from this moment you boys forget that I ever gave advice or assistance in the matter."

"No one shall ever hear your name from us," Jacob said when Lord Gordon paused as if for a reply.

"I shall trust you, my boy, for although I am doing no dishonorable act, as we view the matter, my honor would be at stake if you should incautiously betray my share in this affair. I think now you understand the position which I occupy, and we will say no more about it. This is the only way by which we can aid your friend. If he is here, he will be brought before the court to-morrow; conviction is absolutely certain to follow, and then comes the execution. To plead with General Howe would be not only a waste of words, but cause suspicion in case the boy should escape later. I have here an old pass, signed by the general to visit the prison, issued in blank so that it may be used by any one. I have filled in your names. You will present it boldly at the door. There will be no [59] question raised. You will be conducted to the prisoner's cell, and there you are to remain until a soldier opens the door, and repeats these three words: 'It is time!' Then walk out unconcernedly, all of you. If the plan which I have arranged is successful, you will see no one save the man who gives the signal. It can only fail through some officer or soldier going advertently into the corridor, in which case the prisoner will be in no worse position than before; but you will share his cell because of having attempted to effect his escape. Should this last unfortunately occur, both of you will probably be severely punished—flogged, I should say—and that is the risk which you must take if you would aid Seth. Barring the inopportune coming of some person, the scheme will go through without trouble, for the man on duty is an old follower of mine, upon whom I can depend to the death."

"Will he not be punished for allowing Seth to escape?" Enoch asked.

"That part of it I can manage. All which concerns you is to get yourself and your comrade out of prison once you have entered."

"Where shall we go in case we succeed?" Jacob asked.