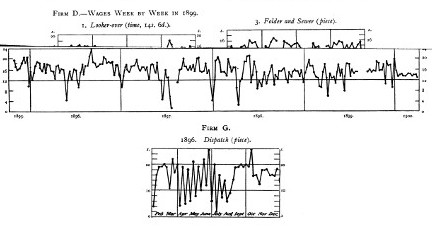

FIRM D.—WAGES WEEK BY WEEK IN 1899.

1. Looker-over (time, 14s. 6d.).

3. Folder and Sewer (piece).

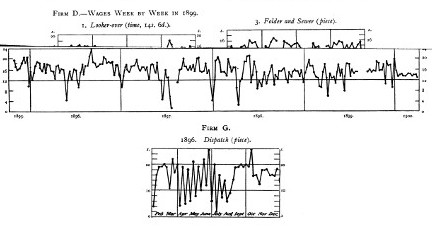

FIRM G.

1896. Dispatch (piece).

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Women in the Printing Trades., by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Women in the Printing Trades.

A Sociological Study.

Author: Various

Editor: James Ramsay MacDonald

Release Date: March 8, 2013 [EBook #42275]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WOMEN IN THE PRINTING TRADES. ***

Produced by Odessa Paige Turner and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from scanned images of public domain material

from the Google Print project.)

WITH A PREFACE BY

PROFESSOR F. Y. EDGEWORTH.

INVESTIGATORS:

MRS. J. L. HAMMOND, MISS A. BLACK,

MRS. H. OAKESHOTT, MISS A. HARRISON,

MISS IRWIN, and Others.

LONDON:

P. S. KING & SON,

ORCHARD HOUSE, WESTMINSTER.

1904.

Transcriber's note: Original spelling variants have not been standardized.

"It should also be noted that slight errors of a few farthings in the

additions have crept into the totals of some of the columns, but as they

do not affect the accuracy of the wage figures the Appendix has been

copied exactly as it was published." (Appendix VI.)

My only qualification for writing this preface is the circumstance that, as a representative of the Royal Economic Society, I attended the meetings of the Committee appointed to direct and conduct the investigations of which the results are summarised in the following pages. From what I saw and heard at those meetings I received the impression that the evidence here recorded was collected with great diligence and sifted with great care. It seems to constitute a solid contribution to a department of political economy which has perhaps not received as much attention as it deserves.

Among the aspects of women's work on which some new light has been thrown, is the question why women in return for the same or a not very different amount of work should often receive very much less wages. It is a question which not only in its bearing on social life is of the highest practical importance, but also from a more abstract point of view is of considerable theoretical interest, so far as it seems to present the paradox of entrepreneurs paying at very different rates for factors of production which are not so different in efficiency.

The question as stated has some resemblance to the well-known demand for an explanation which Charles II. preferred to the Royal Society: there occurs the preliminary question whether the circumstance to be explained exists. The alleged disproportion between the remuneration of men and women is indeed sometimes only apparent, or at least appears to be greater than it is really. Often, however, it is real and great where it is not apparent.

On the one hand, in many cases in which at first sight women[Pg vi] seem to be doing the same work as men for less pay, it is found on careful inquiry, that they are not doing the same work. "The same work nominally is not always the same work actually," as the Editor reminds us (Chapter IV. par. 1). "Men feeders, for instance, carry formes and do little things about the machine which women do not do." In this and other ways men afford to the employer a greater "net advantageousness," as Mr. Sidney Webb puts it in his valuable study on the "Alleged Differences in the Wages paid to Men and to Women for similar Work" (Economic Journal, Vol. I. pp. 635 et seq.). The examples of this phenomenon adduced by Mr. Webb, and in the evidence before the Royal Commission on Labour, are supplemented by these records. To instance one of the less obvious ways in which a difference in net advantageousness makes itself felt, employers say: "It does not pay to train women: they would leave us before we got the same return for our trouble as we get from men." At the same time it is to be noticed in many of these cases that though the work of women is less efficient, it is not so inferior as their pay. For instance, a Manchester employer "estimated that a woman was two-thirds as valuable in a printer's and stationer's warehouse as a man, and she was paid 15s. or 20s. to his 33s.," (p. 47, note).

In other cases the difference between the remuneration of men and women for similar work is not obvious because they work in different branches of industry. For example, only five instances of women being employed as lithographic artists are on record (Chapter IV. par. 1). Other branches of the printing trade are as exclusively women's work. Such data afford no direct and exact comparison between the remuneration of the two classes in relation to the work done by them respectively. As Mr. Webb concludes, the inferiority of women's wages cannot be gathered "from a comparison of the rates for identical work, for few such cases exist, but rather from a comparison of the standards of remuneration in men's[Pg vii] and women's occupations respectively." "Looked at in this light," he continues, "it seems probable that women's work is usually less highly paid than work of equivalent difficulty and productivity done by men." As Mrs. Fawcett points out in an important supplement to Mr. Webb's article (Economic Journal, Vol. II. p. 174), women are crowded into classes of industry which are less remunerative than those open to men.

Recognising the fact of different remuneration for the same amount of work, we have next to consider the causes. It is evident that the sort of explanation offered by Adam Smith for difference of wages in different employments will not avail much in the case with which we are dealing. The lower remuneration of women is not brought about by way of compensation for the greater "agreeableness" or other pleasurable incident or perquisite of their tasks. Possibly we might refer to this head, as well as to others, the circumstance that women having in prospect the hopes of domestic life are likely to take less interest in their trade than men do who cast in their lot for life, if this difference in future prospects is attended with a difference in the effort of attention given to work in the present. But doubtless the explanation is to be found chiefly not in compensation produced by the levelling action of competition, but in the absence of competition between men and women—in the existence of monopoly whether natural or artificial, to use Mill's distinction (Political Economy, Vol. II. Chapter XIV.), together with custom and what Mill calls "the unintended effect of general social regulations."

A natural monopoly is constituted by the superior strength of man, the occasional exercise of which, as just noticed, entitles him to some superiority of pay for work which at first sight may appear almost identical with that of women. The experience recorded in the following pages does not afford any expectation that this kind of superiority tends to vanish. "There is an almost unanimous chorus of opinion that women's work as compositors is so inferior to men's that it does not[Pg viii] pay in the long run" (Chapter IV.). Speaking of the physiological differences between men and women in relation to their work, the Editor concludes that "when all false emphasis and exaggeration have been removed a considerable residuum of difference must remain."

Custom and the somewhat capricious sense of decorum counts for more than might have been expected in restricting women to certain industries, and accordingly, on the principle emphasised by Mrs. Fawcett, depressing their wages. "I know my place, and I'm not going to take men's work from them," said a female operative to an employer who wanted her to varnish books (Chapter IV.). "Why, that is men's work, and we shouldn't think of doing it," was the answer given by forewomen and others to the question why they did not turn their hands to simple and easy processes which were being done by men (Chapter V.).

Among artificial monopolies must be placed that which is constituted by legislation. The Factory Laws, of which a lucid summary is given (Chapter VI. § 1), impose certain conditions on the work of women which, it may be supposed and has been asserted, place them at a sensible disadvantage in their competition with men, who are free from those restrictions. But the evidence now collected goes to prove that the disadvantage occasioned to women in their competition with men by the Factory Acts is not appreciable; thus confirming the conclusions obtained by the Committee which the British Association appointed to consider this very question (Report, 1903). The evidence of the large majority of employers in the printing trade is in favour of the Acts; the evidence of employees is almost unanimous. Of a hundred and three employers "not half-a-dozen remembered dismissing women in consequence of the new enactment" (Chapter VI. § 2). Of a hundred and three employers, who expressed an opinion, twenty-six stated that in their opinion legislation had not affected women's labour at all, sixty considered it to have[Pg ix] been beneficial, and seventeen looked on all legislation as grandmotherly and ridiculous (p. 82). The opinion of the employers is much influenced by the experience that "after overtime the next day's work suffers." The still stronger feeling of the workers in favour of the Factory Acts is partly based on the same fact: "Long hours," said one, "don't do any good, for they mean that you work less next day: if you work all night, then you are so tired that you have to take a day off; you have gained nothing" (p. 86). Upon the whole the moderate conclusion appears to be that "except in a few small houses the employment of women as compositors has not been affected by the Factory Acts" (p. 75). What little evidence there is to the contrary is exhibited by the Editor with creditable candour (p. 80). It is admitted that a "slight residuum of night work" may have been transferred to male hands.

Trades unionism forms another species of "artificial monopoly," the organisation of men in the printing trades being much stronger than that of women. The difference is partly accounted for by the fact, already noticed in other connections, that woman having an eye to marriage is not equally wedded to her trade. Some frankly admit that "marriage is sure to come along, and then they will work in factories and workshops no longer" (p. 42). Whatever the cause, it appears from the Editor's historical retrospect that women's unions have not flourished in the trades under consideration. All attempts to organise women in the printing trade proper, as distinguished from the bookbinding industry, have failed. Even the Society of Women Employed in Bookbinding, though organised by Mrs. Emma Paterson, seems to have had only a moderate success. Thus the men unionists have had their way in arranging that their standard wage should not be lowered by the influx of cheap labour offered by women.

Some unions indeed admit women on equal terms with men, with less advantage to the former than might have been expected. A regulation of this sort adopted by the London[Pg x] Society of Compositors is followed by the result that "it is practically impossible for any woman to join the society" (p. 28). At Perth a few years ago, when women began to be employed on general bookwork and setting up newspaper copy, the men's union decided that the women must either be paid the same rates as the men or be got rid of altogether (p. 46). One general result of such primâ facie equalitarian regulations is probably to promote that crowding of women into less remunerative occupations which was above noticed as a cardinal fact of the situation. It is for this reason apparently that Mrs. Fawcett does not welcome the principle that "women's wages should be the same as men's for the same work." "To encourage women under all circumstances to claim the same wages as men for the same work would be to exclude from work altogether all those women who were industrially less efficient than men" (see the article by Mrs. Fawcett referred to in the Economic Journal, Vol. III. p. 366, and compare her article in that Journal, Vol. II. p. 174, already cited).

Of course it may be argued that, in view of the circumstance that women workers are often subsidised by men and of other incidents of family life, to permit the unrestricted competition of men with women would tend to lower the remuneration and degrade the character of labour as a whole. Without expressing an opinion on this matter, seeking to explain rather than to justify the cardinal fact that the industrial competition between men and women is very imperfect, one may suggest that it is favoured by another element of monopoly. The employer in a large business has some of the powers proper to monopoly. As Professor Marshall says (in a somewhat different connection) "a man who employs a thousand others is in himself an absolutely rigid combination to the extent of one thousand units in the labour market." This consideration may render it easier to understand how it is possible for certain employers to give effect to the dispositions which are attributed to them in the[Pg xi] following passages: "Conservative notions about women's sphere, and chivalrous prejudices about protecting them, influence certain employers in determining what work they ought to do" (p. 52). "A rigid sense of propriety based on a certain amount of good reason, seems to determine many employers to separate male from female departments" (p. 53).

A notice of this subject would be inadequate without reference to the relation between the use of machinery and the competition of women against men. In some cases the cheapness of women's work averts the introduction of machinery. "One investigator whilst being taken over certain large printing works was shown women folding one of the illustrated weekly papers. Folding machines were standing idle in the department, and she was told that these were used by the men when folding had to be done at times when the Factory Law prohibited women's labour" (p. 98). A well-known bookbinder said: "If women would take a fair price for work done it would not be necessary to employ machinery." In the Warrington newspaper offices the cheapness of women's labour makes it unnecessary to introduce linotypes (pp. 46 and 98). On the other hand, in the case of bookbinding, the employment of machinery makes it possible for the less skilled and lower-paid women to do work formerly done by men (p. 48). But the relations are not in general so simple. Rather, as the Editor remarks, "what really happens is an all-round shifting of the distribution of labour power and skill, and a rearrangement of the subdivision of labour" (p. 48). The cheerful assumption proper to abstract economics, that labour displaced by the introduction of machinery can turn to some other employment, is seldom, it is to be feared, so perfectly realised as in the case of the bookbinders below mentioned (p. 48, note): "There was much gloom among the men when the rounding and backing machine came in, but though profitable work was taken away from the 'rounders' and 'backers' they had more 'lining up' and other work to do in consequence, so nobody was turned off."

So far I have adverted to only one of the problems which are elucidated by this investigation. A sense of proportion might require that I should dwell on other topics of great interest such as home work and the work of married women, the technique of the industries connected with printing which the Editor has described minutely, and the statistics relating to women's wages, in the treatment of which a master hand, that of Mr. A. L. Bowley, may be recognised. But I must not go on like the chairman who with a lengthy opening address detains an audience eager to hear the principal speaker. I will only in conclusion express the hope that the Committee which has obtained such useful results may be enabled to prosecute further investigations with like diligence.

F. Y. EDGEWORTH.

The investigation upon which this book is based was undertaken by the Women's Industrial Council; the Royal Statistical Society, the Royal Economic Society, and the Hutchinson Trustees consenting to be represented on the Committee responsible for the work. Upon this Committee, the Women's Industrial Council was represented by Miss A. Black, Miss C. Black, Mrs. Hammond, Mr. Stephen N. Fox, and Mr. J. Ramsay Macdonald; the Royal Statistical Society by Mr. J. A. Baines; the Royal Economic Society by Professor F. Y. Edgeworth, and the Hutchinson Trustees by Mr. A. L. Bowley. Mrs. Hogg also represented the Women's Industrial Council up to her death in 1900.

The Committee takes this opportunity of thanking the Hutchinson Trustees for their liberal financial assistance, and of expressing its appreciation of the services so carefully and enthusiastically performed by the investigators, especially those of Mrs. Hammond, who is mainly responsible for the work done in London; of Mrs. Oakeshott, who assisted Mrs. Hammond; of Mrs. Muirhead, who supplied information about Birmingham; of Miss Harrison, who investigated Bristol and the South-West, and Leeds and district; and of Miss Irwin and Mr. Jones, who were in charge of the Scottish enquiries. To the many employers, Trade Union secretaries, and others who were so willing to give assistance to the investigators, the Committee also desires to express its gratitude.

Whoever has had experience in collecting and sifting such evidence as is dealt with in this investigation knows how difficult it is to arrive at proper values and just conclusions. And women's trades seem to offer special difficulties of this[Pg xvi] kind. There are no Trade Union conditions, no general trade rules, no uniformity in apprenticeships, so far as the woman worker is concerned, and the variations in conditions are most striking, even between neighbouring employers drawing their supply of labour from practically the same district, though perhaps not from the same social strata. That difference in strata is in some cases a predominating factor in women's employment, and it everywhere confuses economic and industrial considerations. When to this irregularity of conditions is added a reticence as to "one's personal affairs," due partly to women's lack of the sense that their position is of public interest, and also partly to an unwillingness shown by many employers to disclose the facts of cheap labour, it can readily be seen that the Committee had to exercise the greatest care in its work.

When the investigation was begun there was an idea that it should be the commencement of an enquiry into women's labour in every trade of any importance, but whether that will be carried on or not will now depend on the reception of this volume and on what further financial assistance is forthcoming. The group of trades selected for first treatment shows neither an overwhelming preponderance of women nor a very marked increase in the employment of women. But it illustrates in a specially normal way the main problems of women's labour under ordinary modern conditions. Upon one important point this group does not throw much light. The employment of Women in the Printing Trades does not show to any satisfactory extent the family influence of married and unmarried women wage earners. What information the Committee was able to gather is dealt with in its proper place, but careful enquiries will have to be made in the highly-organised factory industries before that wealth of fact can be obtained from which conclusions can be drawn, with details properly filled in, regarding the influence of women's earnings upon family incomes.

In other respects these trades have yielded most interesting[Pg xvii] information. They illustrate the industrial mind and capacity of women in the different aspects of training, rates of pay, competition with men, influence of machinery, effect of legislation, and so on. These subjects are dealt with under separate chapters, and though it has been the chief aim of the Committee to present well-sifted and reliable facts, it has stated some conclusions which are most obvious, and which appear to be necessary, if bare figures and dry industrial data are to carry any sociological enlightenment. The volume is therefore offered not as a mere description of industrial organisation, but as a study in sociology which indicates a path ahead as well as points out where we stand at the moment.

Miss Clementina Black is responsible for the description of the Trades, Mr. A. L. Bowley for the Chapter on Wages, and Mr. Stephen Fox for the legal and historical part of that on Legislation. For the rest, the Editor is responsible.

The trades covered by this enquiry include a great number of processes, some brief account of which is necessary if the succeeding chapters are to be comprehensible. It will, perhaps, be the easiest way to follow the stages by which paper is converted into books and to return afterwards to such accessory matters as envelope making, relief stamping, lithography, etc.

Paper-making.—Paper-making is carried on mainly in the counties of Kent, Lancashire, Buckingham, Yorkshire, Fife, Lanark, Aberdeen and Midlothian, but mills are found scattered over the country where water is favourable to the manufacture.[1] In London, there is one mill only, and not more than thirteen women are employed in it. Of these the majority are occupied in sorting esparto grass, and throwing it by means of pitchforks into machines where the abundant dust is shaken out, and from which the grass is carried on moving bands to the vats where it is boiled into pulp. A few older married women are engaged in cutting rags, removing buttons, etc.; but at the present day paper is but rarely made from rags, and the rags so used are generally sorted and cut by machinery. This is an instance in which machinery has undoubtedly superseded the work of women; but, perhaps, few persons[Pg 2] will regret that an occupation so uninviting as the cutting up of old rags should be undertaken rather by a machine than by a human being. With the later processes in the manufacture of paper—the boiling, mixing, bleaching, and refining—women have nothing to do; but a few women are employed in "counting" the sheets of paper before they leave the mill.

[1] The Directory of Paper-makers for 1903 gives the following number of paper mills as being situated in the following counties:—Bucks, 16; Devon, 10; Durham, 9; Kent, 30; Lancashire, 44; Yorkshire, 27; Edinburgh, 17; Lanark, 9; Stirling, 8; Fife, 7; Aberdeen, 5; Dublin, 6.

The work of the women, who are time-workers at from 8s. to 10s. a week, requires no training. The working day begins at 6 a.m., an earlier hour than that of any other factory or shop dealt with in this enquiry. The machinery is kept in constant action, double shifts of men being employed, and when it becomes necessary to feed the machines with grass at night men do the work performed in the day by women.

Letter-press Printing.—The primary business of the "compositor" is to "set-up type," i.e., to arrange the separate movable types in required order for printing successive lines of words. These lines are then arranged in frames called chases, each of which containing the types is known as a forme; the formes are "locked up," that is, made firm by wooden or metal wedges called quoins, and are then carried to the press for a proof impression. The printed page passes on in the shape of proof to the "corrector," and from him to the author, and is then returned in order that corresponding alterations may be made in the placing of the type. Finally, when the whole corrected impression has been printed off, comes the "distributing"—the removal of the types from their places and re-sorting into the proper divisions in the "case." Were books the only form of printed matter, this description would cover the whole business of the compositor, but there are also handbills and newspapers—to say nothing of lithographic printing, which will be dealt with farther on. The printing of handbills, etc., and the printing of newspapers, require, each in its own way, a high degree of skill and experience, to which women, the vast majority of whom leave the trade comparatively young, seldom attain.

In the provinces, however, a few women are engaged upon the printing of weekly or bi-weekly newspapers; and in London, one establishment has been visited in which women regularly do "jobbing" or "display work"—terms which cover the printing of advertisements, posters, handbills, etc.—while at least two other firms employ each one girl upon such work.[Pg 3] "None of the other workers," it is reported, "seem to care to learn."

The difference between skilful and unskilful work in this department is far greater than an uninitiated person might suppose; and the attractiveness of a poster, advertisement or invitation card depends very largely upon the way in which the type is spaced.

In all printing houses employing women compositors, setting up, correcting, and distributing are done by women; in the Women's Printing Society women regularly "impose," that is, divide up the long galleys of type into pages and place the pages so that they may follow in proper order when the sheet is folded, and in another firm a woman was found who could impose; but as a general rule the "imposing" is the work of the man or men employed to lock-up and carry about the heavy formes. No instance has been found in which this latter work, which in some cases is extremely heavy, is done by women.

Bookbinding.—This trade covers at least two main divisions, and one of these is minutely subdivided into a great variety of processes. The first process is, in all cases, that of folding. All printed matter occupying more than a single page has to be so folded as to bring the pages into consecutive order, and this process is essentially the same whether the printed sheet be that of a book, a pamphlet, a magazine, or a newspaper. From the trade point of view, however, there is a distinction between the folding of matter intended to be bound up in a real book cover (book-folding) and matter which is not to be bound (printers' folding). As a general rule—liable, however, to many exceptions—book-folding is performed in a binder's shop and printers' folding in a printing house, whence the names. But many printers now have a regular binding department, and periodical or pamphlet work is on the other hand often folded in the workshop of the publisher's binder. The line of demarcation is therefore no very distinct one. Prospectus work is par excellence printers' folding, and so are such weekly papers as are still folded by hand.

Book-folding is done by women, of whom in theory nearly all, and in practice many, are regularly employed. The process is practically identical in both cases. Printers' folding is carried on in large firms chiefly by a regular staff; but in times of pressure "job hands" or "grass hands" are called in; and in[Pg 4] smaller workplaces job hands do the whole of the work. Great sheets of matter, fresh from the press, are distributed in thousands to the workers to be folded either by hand or by machine. In the latter case, the woman merely feeds the machine, taking care to lay the sheet in exactly the right place. In the former, she becomes practically a machine herself, so monotonous is the occupation. The sheet is folded once, twice, three, or even four times, as the case may be, on a fixed plan, and sometimes has to be cut with a long knife as well as folded. The various sheets of a book having been folded, the process of gathering follows. Each folder has received a fixed number (probably a thousand) copies of the same sheet, and when she has finished folding the gatherer places the sheets in piles of each "signature," e.g. the index letter which one observes on the first page of each sheet in a book, in regular order on a long table. She then walks up and down the side of this table collecting one copy of each sheet and so forming a complete book. The collection thus made passes from the gatherer to the collator, who runs over it, noting by means of the printer's "signature" that all the sheets are in order, and placing her mark on the book, thereby becoming responsible for its accuracy. In the case of illustrated books the process of placing comes at this stage. The plates to be inserted are "fanned out"—i.e., laid out in fan shape—each receives a narrow strip of paste at the back and is placed next, and stuck to, its proper page. This placing is sometimes done by the collator, sometimes by a separate hand. The whole process of collating is often omitted in the case of pamphlets and small work, and the sheets then pass straight from the folder to the stitcher or sewer. Of sewing or stitching there are many varieties. The threads of hand-sewn books generally pass through three bands of tape kept taut by being attached at one end to the table at which the worker sits and at the other to a horizontal bar above. Sometimes the book will have been prepared by the sawing of grooves in the back to receive the sewing. This sawing is done by men. Stitching machines vary greatly. The simplest kind merely inserts the unpleasant "staple-binder" of wire that is so large a factor in the rapid decomposition of cheap books. In these machines, one variety of which uses thread and knots it, the pamphlet or other work in hand is placed at a particular place in a kind of trough; the operator presses a[Pg 5] treadle and the wire is mechanically passed through and pressed flat. Other machines of a more complicated sort will sew with thread upon tapes. In this case one girl is required to superintend and a younger assistant to cut apart the books which are delivered by the machine fixed at intervals upon a long continuous tape. Such machines are worked by power and set going by the pressure of a treadle. Pamphlets or newspapers having neither "cover" nor "wrapper" are now finished—unless, indeed, inserts or insets are to be placed between the pages. These are those unattached advertisements which fall out upon the reader's knee on a first opening, and thereby certainly succeed in catching his attention, though not perhaps his approval. Magazines or paper-covered books are sometimes "wrappered" by women, a simple process consisting of glueing the back of each book and clapping on the cover. Bound books have end-papers added to them by women, who also paste down the projecting tapes to the fly-pages. At this stage the book passes into the hands of men to be touched no more by women, except perhaps in a few subsidiary processes. But since much debate has taken place over the allotment to men and women of other parts of the work, it becomes necessary to give a cursory glance at the further stages of a book's progress.

On leaving the women's hands the book—now no longer a collection of loose sheets but an entity—is placed in a machine to be "nipped," that is, to have the back pressed; then the edges are cut smooth in a "guillotine"; the back is glued upon muslin and rounded, and a groove is made, by hand or machine, at each side of the back, so that the cover may lie flat; this is called "backing," the covering boards and cloth are cut out and pasted together; the design and lettering are stamped upon them in the "blocking-room"; the books are "pasted down," that is, are fixed into their covers by means of pasting down the end leaves, and are "built up" in a large press. If the designs and lettering of the cover are to be gilded, the gold-leaf is laid on by hand according to the stamped-out pattern, which is then restamped, and any gold-leaf not firmly adhering is rubbed off with an old stocking. The stocking is burned in a crucible, and the precious remainder of the gold collected again. "Gold laying-on" is done by women; and the workers engaged in this task do nothing else. Much[Pg 6] dexterity is needed, the gold-leaf being apt to break or blow away at the slightest breath. One investigator describes as "seeming almost marvellous" the skill with which this difficult material is laid in exactly the right place by means of a knife. Women also "open-up," i.e., look through the books ready to be sent out to see that there are no flaws. Such is the life-history of the ordinary book as it comes from the publisher, but "publishers' binding" is not the only section of the binding trade, and is indeed regarded by the workers as "decidedly inferior" to "leather-work," which is emphatically distinguished as "bookbinding." Leather-binding is employed mainly for rebinding. It forms, as may be supposed, a comparatively small part of the whole trade, and is practically confined to three large firms in the West End, a few small places, and separate rooms in some general binding establishments. The chief difference of method lies in the better fixing together of back and cover, the "bound" book being laced into the cover, and in the presence of a "head-band," at top and bottom of the back. Books to be re-bound are picked to pieces by women and cleaned from glue, etc., re-folded, if necessary, collated, and after being rolled flat (by a man) are sewn at a hand press. Repairs to torn pages or plates and the removal of stains are also done by women. This last process demands great care and skill, "foxed" pages requiring to be dipped into a preparation of acid which destroys not only the objectionable stain but also the body of the paper, so that the leaf has to be newly sized and strengthened, and naturally needs very tender handling throughout this whole course of treatment. The best head-bands, too, are made by women by hand, but the head-bands of cheaper books—when they exist at all—are machine-made. Head-band makers form a special and extremely small class of workers.

A third branch of the trade is "vellum-binding," a name which covers the binding of all ledgers, account books, and bank books, whether bound in vellum or no. The workers engaged in this branch form a separate group, are rarely found on the premises of regular bookbinders, and work chiefly in a separate department in printing houses. The employments of women in vellum-binding are much the same as in publishers' binding; they fold and sew much in the usual manner, the only marked difference arising in the case of large day-books, etc.,[Pg 7] which are elaborately hand-sewn in frames, each section of the book having a separate guard of linen.

It is difficult to draw lines of demarcation between the various workers whose occupations have now been described. In large workplaces a worker will probably be kept at one minute process; the folder will do nothing but fold, the sewer will only sew, the collator only collate, and the inserter only insert. Some forewomen, however, think it better to give the women a change of employment. Gold layers-on and openers-up are always entirely apart from folders and sewers, but collators begin with folding and sewing, and in small houses sometimes combine one or both these processes with collating.

The divisions of work between men and women are not made upon any discernible principle of fitness, and except in the case of folding and sewing, which have belonged to women from time immemorial, the various processes began in the hands of men and have been gradually taken up by women. This gradual encroachment has been generally resented and often resisted by the men, and in May, 1893, an elaborate agreement was drawn up by the Bookbinding Trade Section of the London Chamber of Commerce representing the masters, and the secretaries of the men's unions representing the men working in the trade. The women workers were not represented or consulted. The agreement is as follows:—

LONDON SOCIETIES OF JOURNEYMEN BOOKBINDERS.

London Consolidated Society; Bookbinders' and Machine Rulers' Consolidated Union, London Branch; Society of Day-working Bookbinders.

That this meeting of representatives of the Bookbinding Section of the London Chamber of Commerce, with representatives of the Journeymen Bookbinders' Trade Societies, deeming it desirable that a definition of bookbinding should be agreed upon for the delimitation of work to be paid for at recognised rates, hereby agrees that the following divisions or sub-divisions of labour be for the future recognised as the work of bookbinders or apprentices, taking the book from the time of[Pg 8] leaving the women after sewing, except wrappering, which is unaffected by this agreement:—

Forwarding, and the following sub-divisions of bookbinding:

Nipping, knocking down, or pressing.

Cutting books or magazines.

Colouring edges of books (where done indoors).

Cutting leather, except corners, and backs for flush work from sheep and roan.

Cutting cloth.

Cutting hollows and linings.

Cutting boards.

Bevelling boards.

Case making.

Pasting down and building up.

Flush work throughout.

Finishing throughout.

Assistant finishing throughout.

Blocking throughout.

Circuit and box work. (Bible trade.)

PROVIDED:—That the representatives of the journeymen agree that they will not make it a grievance if female or unskilled labour is placed upon:—

The rolling, pressing before sewing, sawing up, or papering of outboard work.

The laying on, washing up, or cleaning off of cloth work.

The varnishing of cloth or Bible work.

The paper mounts and pictures on cloth cases.

Taking work out of the press after pasting down, and opening up.

The carrying of loads of work about the workshop.

Further, that the representatives of the journeymen will not object to the introduction of unskilled labour upon cloth cutting, if the recognised rate of wages of 32s. per 48 hours be paid after a probationary period of twelve months, in which the novice may learn the work.

Owing to the difficulties of drafting a clause affecting the laying on in such a manner as to lay down a line of demarcation between cloth and leather work, it is hereby agreed to leave the subject of laying on in statu quo, upon the understanding that it shall not be the policy of the Trade Societies to interfere, except in the case of innovations upon existing custom.[2]

[2] This clause has been interpreted by the award given in March, 1903, by Mr. C. J. Stewart, the arbitrator appointed by the Board of Trade to settle a dispute in the trade regarding wages, hours, apprentices and piece work. The 6th clause in that award is as follows:——"That the right or practice existing with regard to female labour employed on wrappering and for laying on gold in case work, cloth or leather, or other material, in certain workshops in the trade, shall be made to apply to all workshops in the trade, it being agreed by the employers that no man exclusively employed in gold laying-on shall lose his employment by reason of the employment of women on such work."

This agreement not to be construed to the prejudice of the existing holders of situations.

Adopted by the Bookbinding Trade Section of the London Chamber of Commerce at its annual meeting on 7th May, 1893.

JOHN DIPROSE, Chairman.

Ratified by the executives of the hereunder-mentioned Societies on May 30th, 1893, and signed on their behalf.

HENRY R. KING, Secretary, London Consolidated Society.

WILLIAM BOCKETT, Secretary, Day Working Bookbinders' Society.

THOMAS E. POWELL, Secretary, Bookbinders and Machine Rulers' Consolidated Union (London Branch).

Closely connected with vellum-binding are the processes of machine-ruling, numbering, paging and perforating.

Machine-ruling is the process by which lines are ruled for ledgers, invoices, etc. The machine employed resembles a hand-loom in appearance, and is in effect a framework in which pens are fixed at the required distances. Ink is conveyed into these from a pad of thick flannel above, and the page to be ruled lies on a broad band below. The re-inking of the flannel is in some cases effected by means of a reservoir and tap supplying a regulated flow, in others the ink is laid on from bowls of red or blue colour by means of a brush. Machines worked by a handle still survive in a few places, but as a general rule the machine is driven by power and the operator merely superintends, correcting the machine if it goes wrong, setting the pens and regulating the supply of ink. The newest machines require the services of neither "feeders" nor "wetters," and the simple old picturesque accessories, the cords, the wooden frame, the bowls of colour, are disappearing. Women are employed in some houses to feed the machines, which is purely[Pg 10] mechanical work; our investigators found four establishments in London in which women can rise to the higher position of "minder," and one other in which they are allowed to damp the flannel and partially "mind."

Numbering is the process by which consecutive figures are stamped upon cheques, bills, receipts, tickets, or other loose sheets. A machine worked by hand is employed, the number types changing automatically. The attention of the worker is required on three points only: the paper must be placed so as to bring the number into the right position; the machine must not be allowed to skip numbers at a jump—as it is inclined to do; and whenever an additional figure becomes necessary, a certain change must be made. The handle of the machine works up and down, and the process is different from that of stamping, to be described later. There are no power machines for numbering.

Numbering is said to try the eyes, and the working of a machine handle is considered bad for girls who have any weakness of the chest.

Paging is the process by which numbers are printed upon the pages of a bound volume. As in numbering, a change has to be made at each "100"; and there is need of further care to avoid missing pages. Where these are thin or interleaved with tissue paper omissions are very easily made.

Perforating is done by machines generally worked by power, but sometimes by treadle, with one foot; and this treadle work was described by a woman constantly employed at it as excessively hard work.

Lithography.—The work of women and girls in lithography seems to be confined to the feeding of machines. In London the introduction of female labour is comparatively recent, dating from about six or seven years ago, but in the provinces women have been employed for more than thirty years. Employers are, for some reason or another, not very ready to give information about this branch of work; but some of the investigators engaged in this enquiry have succeeded in seeing the process. A girl stands on a high platform putting sheets into the proper place in the machine until she has completed the job. A long interval may follow in which she may sew, knit or read. The noise of the machine is incessant, and the work hard, monotonous and mechanical, but if done under proper[Pg 11] conditions not necessarily unhealthy. Many working-places in London, however, where space is so valuable, are partly underground, dark and ill-ventilated, and in these the ceaseless whirring noise and the smell of the ink grow unendurably trying. Workers in such places are rough and of low social standing. Most men working in the general stationery trades, and some employers who do not employ women, condemn the doing of this work by women, and since the women have superseded not men but boys, the views of the workmen are not those of trade rivals. Girls are said to be in various ways better workers than boys—cleaner-handed, more careful and accurate, less disposed to meddle with the machinery, and therefore less liable to accidents; above all, quieter, more docile, and less apt to strike. The men employed in lithography look favourably on the employment of girls, because no girl attempts to rise into the higher grades and "pick up" the trade without apprenticeship. Girls do not, and boys as feeders do, "constitute a danger to the Society." Moreover, a trade that offers only so uncertain a chance of rising is generally disapproved for a boy.

The objection to the employment for girls is that they work among men—an objection which may be a very grave one indeed, or a comparatively slight one, according to the character of the foreman and the management of the workshop. It may be noted that respectable working-class parents almost always consider this objection serious.

A few women are reported to be employed as lithographic artists, but no one has been seen in the course of this enquiry.

Minor stationery trades are envelope-making, black bordering, plain and relief stamping.

Envelope-making has several subdivisions. The paper is first cut to shape in machines worked by men, then passed to women to be "cemented," i.e., to be gummed upon the flaps, folded or "creased," and stuck together. Finally the envelopes are packed by women.

Cementing and folding are reckoned distinct trades. One cementer explained to an investigator, however, that she described herself as a folder, "for people are so ignorant that if you say you are a cementer they think you have something to do with the pavement." Cementing may be done by hand or by machine, and the workers are not interchangeable. The hand-worker spreads out the envelopes in the shape of a fan,[Pg 12] and passes her brush over all the flaps at once. The machine-cementer puts 500 or 1,000 envelopes into a small machine, which grips them and drips gum upon their flaps. The worker extricates the envelopes one by one, and spreads them out to dry. A more complex machine is being introduced which performs the various processes for itself, requiring one girl to feed and one to take-off.

The flaps being dry, the envelopes are taken in bundles to the folders, who first "crease" them—that is, fold in the sides—then "gum" them with a brush at the required points, and fasten them. This process can also be performed by a machine, and the operator in that case merely feeds the machine with the cemented paper, and the envelope is delivered made.

The envelopes are then handed on to the "packers," who count them and make them up into packets, and the packets into parcels.

Except the original cutting, still done by men, all these processes have always been executed by women.

The trade of black bordering is carried on by women who seldom or never perform any other process. Black bordering is usually done by hand. The worker spreads out a number of sheets, cards or envelopes, in such a manner as to expose only a certain width of border, and over this exposed portion she passes a brush. Of course, only two edges of each sheet, etc., can be laid ready at one time, and each object has to be "laid out" a second time after drying. "It is marvellous to see the speed and dexterity with which the women do the 'laying-out.' They gather up a large number of sheets, lay them on the board and fan them out with a piece of wood used for the purpose, showing the most astounding accuracy of eye in leaving just the right width exposed. Sometimes the 'laying out' is done by a machine, and only the blacking by hand." This trade—a steady one on the whole—has, unlike nearly all the other stationery trades, been more prosperous owing to the South African war—a grim little example of the way in which large public events eddy away into undreamed of backwaters! Men now never do black bordering, but are reported to have done so once. Machinery is now being more widely introduced.

Plain, Relief and Cameo Stamping.—Under these heads are included all the various processes by which crests, monograms,[Pg 13] addresses, etc., are embossed upon notepaper, cards, programmes, or private Christmas cards. The trade has increased enormously of late years, and a new process has been introduced which renders it possible to employ the printing press. This, however, is only worth while when the order to be executed is a very large one; and most stamping is done by hand machines, a die being fixed into the machine and impressed by tightly screwing down. The machine is worked (like an ordinary copying press) by a horizontal bar, having a ball at each end, and swung from right to left. The lighter machines can be worked by one hand; the heavier require two, and are found fatiguing. Some are so heavy that they can only be worked by men. Practice is necessary in order to get the stamp in exactly the right place, and, in relief or cameo work, in order to mix the colours, which are rubbed on the die, to precisely the right thickness.

Plain stamping—the easiest process—is that in which letters, a coat of arms, or a trade mark, are raised but not coloured; in relief stamping the raised surface is coloured; and in cameo stamping (of which the registered letter envelope is an example) a white device stands out from a coloured background.

When two or more colours are employed considerable care, skill, and patience are needed. This work, in two or more colours, is called illuminating; in one branch of it—the highest—gold and silver are employed on a coloured surface, and here women are not employed.

Show-card Mounting.—Card mounting is a distinct trade, and is almost entirely in female hands. Almanacs, advertisements, and texts for hanging up, all belong to the province of the card mounter, whose main business is to unite the picture and cardboard that arrive separately in her workshop. The board is first cut either by a man at a cutting machine—or "guillotine"—or occasionally by a girl at a rotary machine adjustable to different gauges; then "lined," by having paper pasted over the back and edges. Inferior work is not lined. Finally, the picture or print is pasted on the card, the backs of three or four pictures being pasted at once, and each in succession being applied to its own card. Some means of hanging up is still needed, and various methods are in use. Sometimes eyelets are inserted into a punched hole by means of a small machine which a girl works by hand. Sometimes the edge is bound[Pg 14] with a strip of tin, having loops attached to it; in this case the tin strips are cut by men, and applied by hand machines, again worked by girls. Sometimes, as in the case of maps, charts, and large diagrams, a wooden rod is fixed at the top, this fixing being done by girls.

The trade is not, it will readily be perceived, one that demands great skill, practice or intelligence, and the majority of the workers are very young. Still, a certain degree of experience is necessary, since the application of either too much or too little paste results in a "blister," and blistered work is spoiled. One investigator was shown a lot of 500 cards, the estimated value of which was 6d. each, no less than 385 of which had thus been spoiled and rendered quite useless. The workers stand at their work and report that it exhausts them. It used, till about twenty-eight years ago, to be done by men; but the trade was at that time a much smaller one. Night work, when considered necessary, is still done by men.

A little laying-on of gold is done in connection with card mounting. The process has been described already under bookbinding.

The Christmas card industry (which may be considered as a variety of show-card mounting) serves to exemplify one of the anomalies of the Factory Act. These cards may be sorted, packed, etc., to any hours of the night, because mere packing is not regarded as manufacture; but if a "bow of ribbon" is to be affixed to each card, the process becomes "preparation for sale," and the regulations of the Act apply.[3]

[3] Cf. pp. 76,77.

Typefounding.—Typefounding is a small, ancient and conservative trade into which women have only crept during the last few years. In London there are only about eight typefoundries proper, and in these labour is elaborately subdivided, every workman performing but one process. Recently, however, some large printing houses have begun to cast their own type, and in these the few men employed perform all the processes, or, to use their own term, "do the work through," thus, curiously enough, reverting to an earlier stage in the development of the trade.

Women are employed in the large foundries, where they perform certain subsidiary parts of the work. Each type when[Pg 15] it comes from the machine wherein it has been cast has a little superfluous bit of thin metal, known as a "break" on its end or "foot." These bits are broken off by girls, the "foot" of the type being pressed against a table and the "break" snapped off. No great skill is required, but quickness only comes with practice. The type is also "set-up"—i.e., put in rows in a long stick or "galley"—by girls; here, again, nothing is needed beyond a certain manual dexterity. Sometimes another stage, "rubbing," intervenes between the "breaking" and the "setting-up." Rubbing is merely the smoothing off on a flat grindstone of any roughness that may be left by the machine round the "face" end of the type. In one case, in London, one or two women were once employed in rubbing, but none appear to be so engaged at present, and the newer appliances have made rubbing unnecessary. "Dressing," the final process through which the type passes, is said to be in some places performed by women; but no such instances have been found in London in the course of this investigation. The dresser receives the lines or sticks of type, polishes the sides, measures their length and breadth with a delicate spanner, "nicks" the foot of each type, and finally "picks over" the type—that is, scans the row of "faces" through a magnifying glass, and rejects any on which the letters are not absolutely truly placed.

One large London firm, employing many girls, has a different process. The types are cast in long lines and have to be divided, no breaking or setting-up being required. As one of the workers said, "This is not a trade; just any one can do it!"

Girls began to do "breaking" and "setting-up" in London about thirteen years ago. There were then but thirteen so employed. During the last few years their numbers have increased, and it is estimated that those now employed number from 100 to 150. One firm is known to employ fifty and another forty. They have superseded boys, and were mainly introduced because boys were difficult to get. The chances of rising being small for boys, they were disinclined to enter the trade. The chances for girls are nil, but this consideration does not weigh much with girls belonging to the class that supplies workers to typefounding. The female workers are all young, and at present no married women seem to be employed, a fact which may perhaps be due to the comparatively recent entrance of women into the trade.

The occupation has a special feature of unhealthiness—the danger of lead-poisoning; and the Factory Act, recognising this, prohibits women, young persons or children, from taking a meal upon the premises where typefounding is carried on. As in other lead industries, much depends on the care and cleanliness of the worker. To eat with hands lead-blackened by some hours of "breaking-off" is to run considerable risk of lead-poisoning. It is suggested that girls, being more fastidious than boys upon such points, may possibly suffer less frequently from the dangers involved in the industry of typefounding.

Before 1841 the census occupation tables do not state the numbers employed in the detailed trades, and even in that year we find either that no separate return was made for some of the industries with which this volume deals, or that no women were employed at all. Presumably, therefore, previous statistics would not have shown that women were employed in these industries to any appreciable extent.

The following tables show the employment of women in England and Wales and Scotland in the Printing and Kindred Trades according to the census returns from 1841 to 1901. The figures must be used with caution, as they include employers as well as employed (an error, however, which is immaterial in the case of women workers). Subsidiary helpers are also classified with those actually entitled to be regarded as members of the trade, and the tables do not discriminate sufficiently between the various subdivisions of occupations. These last two errors considerably affect the figures relating to women. In the bookbinding section, for instance,[4] the figures are altogether misleading, since by far the greater number of women included as bookbinders are really paper and book-folders, and are no more entitled to the name bookbinder than a bricklayer's labourer is to that of bricklayer.

[4] Since 1881 in the Scottish returns.

ENGLAND AND WALES.

Census 1841. (Employers and Employed included.)

| Males. | Females. | |

|---|---|---|

| Booksellers, bookbinders, etc. | 8,873 | 2,035 |

| Printers | 15,582 | 161 |

| Lithographers, etc. | 667 | 12 |

| Paper manufacture | 4,375 | 1,287 |

| Paper rulers | 113 | 16 |

| Paper stainers | 1,243 | 92 |

| Type founders | 629 | 6 |

| Vellum binders | 131 | 3 |

Census 1851. (Employers and Employed included.)

| Males. | Females. | |

|---|---|---|

| Bookbinders | 5,501 | 3,926 |

| Printers, etc. | 23,568 | 3,926 |

| Lithographers (Great Britain) | 1,984 | 6 |

| Paper manufacture | 6,123 | 4,686 |

| Paper stainers | 2,001 | Not enumerated. |

Census 1861. (Employers and Employed included.)

| Males. | Females. | |

|---|---|---|

| Bookbinders | 6,556 | 5,364 |

| Printers | 30,171 | 419 |

| Lithographers, etc. | 3,588 | — |

| Paper manufacture | 7,746 | 5,611 |

| Machine rulers | 564 | 54 |

| Envelope makers | 179 | 860 |

| Paper stainers | 1,556 | 399 |

| Type founders | 863 | 11 |

Census 1871. (Employers and Employed included.)

| Males. | Females. | |

|---|---|---|

| Bookbinders | 7,917 | 7,557 |

| Printers | 44,073 | 741 |

| Lithographers, etc. | 3,785 | Not enumerated. |

| Paper manufacture | 10,142 | 6,630 |

| Envelope makers | Not enumerated. | 1,477 |

| Paper stainers | 1,311 | 448 |

Census 1881. (Employers and Employed included.)

| Males. | Females. | |

|---|---|---|

| Bookbinders | 9,505 | 10,592 |

| Printers | 59,088 | 2,202 |

| Lithographers, etc | 6,009 | 147 |

| Paper manufacture | 10,352 | 8,277 |

| Envelope makers | 175 | 1,933 |

| Paper stainers | 1,822 | 445 |

| Type cutters and founders | 1,137 | 32 |

Census 1891.[Pg 19]

| Employers. | Employed. | Working on Own Account. |

Others not Specified. |

TOTAL. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bookbinders | M. | 615 | 10,038 | 355 | 479 | 11,487 |

| Bookbinders | F. | 72 | 13,401 | 74 | 702 | 14,249 |

| Printers | M. | 3,979 | 73,288 | 1,052 | 3,640 | 81,959 |

| Printers | F. | 158 | 4,133 | 32 | 204 | 4,527 |

| Lithographers, etc. | M. | 499 | 7,486 | 359 | 292 | 8,636 |

| Lithographers, etc. | F. | 9 | 309 | 7 | 24 | 349 |

| Paper manufacture | M. | 396 | 11,081 | 97 | 440 | 12,014 |

| Paper manufacture | F. | 12 | 7,598 | 29 | 390 | 8,029 |

| Envelope makers | M. | 9 | 260 | 6 | 14 | 289 |

| Envelope makers | F. | 2 | 2,339 | 13 | 104 | 2,458 |

| Paper stainers | M. | 135 | 1,861 | 60 | 78 | 2,134 |

| Paper stainers | F. | 10 | 370 | 7 | 16 | 403 |

| Type cutters and founders | M. | 35 | 1,204 | 23 | 52 | 1,314 |

| Type cutters and founders | F. | 1 | 49 | 0 | 5 | 55 |

Census 1901.

| Employers. | Employed. | Working on Own Account. |

Others not Specified. |

TOTAL. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bookbinders | M. | 554 | 11,609 | 388 | 113 | 12,664 |

| Bookbinders | F. | 46 | 18,933 | 82 | 162 | 19,223 |

| Printers | M. | 4,805 | 89,306 | 1,603 | 774 | 96,488 |

| Printers | F. | 117 | 9,463 | 48 | 65 | 9,693 |

| Lithographers, etc. | M. | 496 | 9,648 | 445 | 93 | 10,682 |

| Lithographers, etc. | F. | 7 | 1,015 | 14 | 7 | 1,043 |

| Paper manufacture | M. | 337 | 14,920 | 47 | 55 | 15,359 |

| Paper manufacture | F. | 11 | 8,815 | 7 | 18 | 8,851 |

| Envelope makers | M. | 14 | 352 | 1 | 3 | 370 |

| Envelope makers | F. | 6 | 3,113 | 1 | 23 | 3,143 |

| Paper stainers | M. | 45 | 1,928 | 34 | 25 | 2,032 |

| Paper stainers | F. | 2 | 280 | 1 | 4 | 287 |

| Type cutters and founders | M. | 35 | 1,223 | 15 | 14 | 1,287 |

| Type cutters and founders | F. | 0 | 181 | 0 | 2 | 183 |

| Stationary manufacture | M. | 352 | 3,910 | 91 | 28 | 4,381 |

| Stationary manufacture | F. | 24 | 4,615 | 12 | 47 | 4,698 |

SCOTLAND.

Census 1841. (Employers and Employed included.)[Pg 20]

| Males. | Females. | |

|---|---|---|

| Booksellers, bookbinders, etc. | 2,164 | 283 |

| Printers | 2,446 | 21 |

| Lithographers, etc. | 234 | 1 |

| Paper manufacture | 732 | 738 |

| Paper rulers | 61 | 8 |

| Paper stainers | 31 | 1 |

| Type founders | 292 | — |

Census 1851. (Employers and Employed included.)

| Males. | Females. | |

|---|---|---|

| Bookbinders | 1,091 | 710 |

| Printers, etc. | 3,526 | 710 |

| Paper manufacture | 1,265 | 2,159 |

| Paper stainers | 49 | Not enumerated. |

Census 1861. (Employers and Employed included.)

| Males. | Females. | |

|---|---|---|

| Bookbinders | 1,174 | 100 |

| Printers | 4,400 | 70 |

| Lithographers, etc. | 1,101 | 2 |

| Engravers | 651 | 6 |

| Bookfolders | 2 | 1,094 |

| Machine rulers | 171 | 18 |

| Paper manufacture | 1,648 | 2,773 |

| Envelope makers | 5 | 309 |

| Paper stainers | 77 | — |

| Type founders | 434 | — |

Census 1871. (Employers and Employed included.)

| Males. | Females. | |

|---|---|---|

| Bookbinders | 1,293 | 174 |

| Printers | 5,476 | 113 |

| Lithographers, etc. | 1,125 | 36 |

| Print and map colourers | 192 | 57 |

| Bookfolders | — | 1,646 |

| Paper manufacture | 2,770 | 3,504 |

| Envelope makers | 7 | 412 |

| Paper rulers | 214 | 100 |

| Paper stainers | 110 | 50 |

| Type founders | 496 | — |

Census 1881. (Employers and Employed included.)

| Males. | Females. | |

|---|---|---|

| Bookbinders | 1,433 | 2,587[x] |

| Printers | 6,936 | 839 |

| Lithographers, etc. | 1,269 | 153 |

| Map and print colourers and sellers | 50 | 41 |

| Paper rulers | 188 | 115 |

| Paper manufacture | 3,363 | 4,612 |

| Envelope makers | 32 | 580 |

| Paper stainers | 34 | 97 |

| Type cutters and founders | 471 | 71 |

[x] Bookfolders are included here.

Census 1891.

| Employers. | Employed. | Working on Own Account. |

Others not Specified. |

TOTAL. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bookbinders | M. | 68 | 1,413 | 13 | 22 | 1,516 |

| Bookbinders | F. | 3 | 2,865 | 3 | 18 | 2,889 |

| Printers | M. | 322 | 8,367 | 69 | 84 | 8,842 |

| Printers | F. | 5 | 1,417 | 1 | 7 | 1,430 |

| Lithographers, etc. | M. | 109 | 1,516 | 22 | 10 | 1,657 |

| Lithographers, etc. | F. | — | 397 | 1 | 2 | 400 |

| Paper rulers | M. | 10 | 315 | 1 | 13 | 339 |

| Paper rulers | F. | 1 | 192 | — | 4 | 197 |

| Paper manufacture | M. | 107 | 4,332 | 21 | 51 | 4,511 |

| Paper manufacture | F. | 3 | 4,546 | 4 | 66 | 4,619 |

| Envelope makers | M. | 3 | 33 | 2 | — | 38 |

| Envelope makers | F. | — | 698 | 1 | — | 699 |

| Paper stainers | M. | 6 | 113 | 1 | — | 120 |

| Paper stainers | F. | — | 28 | — | — | 28 |

| Type cutters and founders | M. | 9 | 496 | 3 | 4 | 512 |

| Type cutters and founders | F. | — | 75 | — | — | 75 |

Census 1901.

| Employers. | Employed. | Working on Own Account. |

Others not Specified. |

TOTAL. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bookbinders | M. | 67 | 1,422 | 16 | — | 1,505 |

| Bookbinders | F. | 4 | 3,522 | 4 | — | 3,530 |

| Printers. | M. | 378 | 9,643 | 54 | 2 | 10,077 |

| Printers. | F. | 7 | 2,852 | 1 | — | 2,860 |

| Lithographers, etc. | M. | 87 | 1,640 | 25 | — | 1,752 |

| Lithographers, etc. | F. | 2 | 728 | 1 | — | 731 |

| Paper manufacture | M. | 103 | 4,860 | 6 | 1 | 5,000 |

| Paper manufacture | F. | 2 | 4,653 | — | — | 4,655 |

| Envelope makers | M. | 4 | 53 | — | — | 57 |

| Envelope makers | F. | 1 | 895 | — | — | 896 |

| Paper stainers | M. | 1 | 120 | 1 | — | 122 |

| Paper stainers | F. | — | 52 | 1 | — | 53 |

| Type cutters and founders | M. | 6 | 419 | 5 | — | 430 |

| Type cutters and founders | F. | — | 53 | — | — | 53 |

| Stationery manufacture | M. | 22 | 95 | 1 | — | 118 |

| Stationery manufacture | F. | 1 | 492 | 3 | — | 496 |

In 1896 the Home Office began to publish as an appendix to the Chief Factory Inspector's Report a series of figures of occupation which were exceedingly valuable for purposes of comparison, and in time would have been the best existing statistical index of industrial movements. Unfortunately these figures have not been published since 1899; but for the years that they were issued, those relating to the printing trades were as follows:—

FACTORY INSPECTOR'S REPORTS.

Paper, Printing, Stationery, Etc. (Includes all the industries under this section.)

| Total Male. |

Total Female. |

Male over 18. |

Female over 18. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895 | Factories. | 159,987 | 63,626 | 123,895 | 42,904 |

| Workshops. | 3,355 | 4,692 | 2,224 | 3,073 | |

| Total. | 163,342 | 68,318 | 126,119 | 45,977 | |

| 1896 | Factories. | 169,500 | 68,769 | 131,166 | 45,632 |

| Workshops. | 4,508 | 5,919 | 3,152 | 3,898 | |

| Total. | 174,008 | 74,688 | 134,318 | 49,530 | |

| 1897 | Factories. | 171,151 | 69,898 | 134,221 | 45,479 |

| Workshops. | 4,458 | 6,305 | 3,192 | 4,192 | |

| Total. | 175,609 | 76,203 | 137,413 | 49,671 | |

| 1898-99[x] | Factories. | 173,964 | 72,833 | 137,504 | 46,681 |

[x] Factories only.

SOME DETAILS OF ABOVE.

Paper-making.

| Total Male. |

Total Female. |

Male over 18. |

Female over 18. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895 | Factories | 21,263 | 11,008 | 18,271 | 8,935 |

| 1896 | 22,091 | 11,744 | 18,777 | 9,403 | |

| 1897 | 22,174 | 11,309 | 19,086 | 9,138 | |

| 1898-99[x] | 22,340 | 11,506 | 19,158 | 9,197 |

[x] Factories only.

Bookbinding.

| Total Male. |

Total Female. |

Male over 18. |

Female over 18. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895 | Factories | 11,791 | 16,098 | 9,304 | 10,802 |

| 1896 | 13,300 | 17,159 | 10,580 | 11,498 | |

| 1897 | 14,661 | 20,877 | 11,705 | 13,985 | |

| 1898-99[x] | 14,893 | 22,555 | 12,046 | 14,653 |

[x] Factories only.

Letter-press Printing.

| Total Male. |

Total Female. |

Male over 18. |

Female over 18. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895 | Factories | 104,162 | 19,974 | 80,232 | 12,699 |

| 1896 | 104,860 | 20,634 | 80,719 | 12,732 | |

| 1897 | 100,629 | 14,473 | 79,124 | 8,725 | |

| 1898-99[x] | 102,800 | 13,348 | 81,598 | 8,283 |

[x] Factories only.

Lithography, Engraving and Photography.

| Total Male. |

Total Female. |

Male over 18. |

Female over 18. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895 | Factories | 12,789 | 4,516 | 9,024 | 2,735 |

| Workshops | 2,226 | 1,425 | 1,494 | 943 | |

| 1896 | Factories | 14,854 | 5,252 | 10,572 | 3,076 |

| Workshops | 3,116 | 2,146 | 2,224 | 1,437 | |

| 1897 | Factories | 17,960 | 6,278 | 12,867 | 3,451 |

| Workshops | 2,794 | 2,115 | 2,076 | 1,477 | |

| 1898-99[x] | Factories | 17,737 | 6,457 | 12,727 | 3,522 |

[x] Factories only.

Machine Ruling.

| Total Male. |

Total Female. |

Male over 18. |

Female over 18. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895 | Factories | 664 | 482 | 408 | 170 |

| Workshops | 233 | 134 | 97 | 45 | |

| 1896 | Factories | 981 | 599 | 594 | 197 |

| Workshops | 269 | 168 | 135 | 59 | |

| 1897 | Factories | 1,764 | 1,414 | 1,115 | 538 |

| Workshops | 322 | 166 | 163 | 57 | |

| 1898-99[x] | Factories | 2,062 | 1,571 | 1,328 | 534 |

[x] Factories only.

Paper Staining, Colouring and Enamelling.

| Total Male. |

Total Female. |

Male over 18. |

Female over 18. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895 | Factories | 4,254 | 983 | 2,916 | 540 |

| Workshops | 102 | 28 | 74 | 16 | |

| 1896 | Factories | 4,468 | 1,065 | 3,114 | 577 |

| Workshops | 138 | 70 | 111 | 42 | |

| 1897 | Factories | 4,795 | 1,368 | 3,395 | 784 |

| Workshops | 40 | 66 | 33 | 38 | |

| 1898-99[x] | Factories | 4,874 | 1,320 | 3,529 | 746 |

[x] Factories only.

Envelope Making.

| Total Male. |

Total Female. |

Male over 18. |

Female over 18. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1897 | Factories | 1,203 | 4,156 | 896 | 2,865 |

| Workshops | 37 | 292 | 25 | 191 | |

| 1898-99[x] | Factories | 1,405 | 4,996 | 1,030 | 3,313 |

[x] Factories only.

These figures must not be compared with the census returns as they relate only to those establishments making reports to the Factory Inspectors under the Factory and Workshop Law.

The subdivision of labour which has broken up the original printing "profession" into a score or so of different trades, each minutely subdivided in turn, has been the chief cause of the employment of women in this industry in modern times, although it appears that nuns were engaged as compositors at the Ripoli Monastery Press in Florence towards the end of the fifteenth century,[5] within half a century of the introduction of printing. Only very exceptional women could obtain a footing in a profession which embraced typefounding, ink-making, press-carpentry, composing, folding, and bookbinding. The United States, where, in so many respects, women have stepped in advance of European conditions, boasts of Jenny Hirsch, who carried on a printer's business in Boston about 1690, and during the next two centuries women printers were common in the thirteen States. It was a woman, Mary Catherine Goddard, who printed the first issue of the "Declaration of Independence." The years of the French Revolution also seem to be marked by the number of women engaged in the printing trade, whether owing to the general emancipating impulses of the time or to the increased demand for compositors, is not quite clear. The amiable and eccentric Thomas Beddoes, moved by the interest he took in social affairs, and inspired by the emancipatory movement of his time, had been struck with the opening which the printing trades seemed to offer to women, and gave his "Alexander's Expedition"[6] to a woman of his village, Madely, to set up. "I know not," he wrote in the Advertisement to the book, "if women be commonly engaged in printing, but their nimble and delicate fingers seem extremely well adapted [Pg 25]to the office of compositor, and it will be readily granted that employment for females is amongst the greatest desiderata of society." In England, however, the labour of women outside their homes continued to be extremely limited, and the printing trades were confined to men. During the eighteenth century women seem to have been employed in folding and sewing book and news sheets, but they did not come into the trade in any considerable numbers until the nineteenth century was half spent. This was very largely owing to the heavy nature of the work and the long apprenticeship necessary to master the varied details of the craft. The Provincial Typographical Society's first constitution, issued in 1849, shows that at so recent a date the typographical apprentice had to learn "printing and bookbinding" or "printing and stationery."[7] The printing press used in 1800 was practically the same as that used by Gutenberg in 1450.

[5] Printers' Register, August 6th, 1878, quoting Journal für Buchdruckerkunst.

[6] Published in 1792.

[7] Typographical Association: "Fifty Years' Record," p. 4.

The enormous advance in the printing trades owing to the abolition of the stamp duties and the paper tax, together with the spread of education and improvement in the facilities for publishing, with their resulting large demand for printed matter, speedily revolutionised these trades and led to the introduction of the great machines. Pressmen became differentiated from compositors, "minders" from layers-on or takers-off, jobbers from book-hands, folders from makers-up; whilst bookbinding finally became a separate trade altogether. Some of these separate processes, needing but little skill and requiring no apprenticeship, involving no heavy labour and no responsibility, offered openings for women.

One of the earliest references to women made by the Typographical Association occurs in 1860, when the Executive of the Union mentioned them in its half-yearly report. Printing houses were then closed to Union members on account of the employment of women. The Typographical Society's Monthly Circular for August, 1865, for instance, states that a Bacup newspaper office was closed to members of the Typographical Union, owing to the employment of female labour. The exact form of employment is not given. Again, in the report for June, 1866, the Executive of the Union refers to having trouble with an employer who[Pg 26] tried to employ female labour, but who had failed "to get suitable applicants of the gentle sex." In 1886 it was agreed that women should be admitted to both the Typographical Association and the London Society of Compositors on the same terms as men, but only one woman has availed herself of this resolution.[8]

[8] She joined the London Society of Compositors on August 30th, 1892, but she has now ceased to be a member.

At this point, the movement for the emancipation of women contributes an interesting chapter to the history of these trades.

The printing trades were regarded by a few of the leading spirits in the agitation for "Women's Rights" as being well adapted to women's skill and physique, and in 1860 Miss Emily Faithfull not only started the Victoria Press, in which women alone were to be employed, but directed the attention of women generally to the openings afforded them by this group of trades. "The compositor trades," the Englishwoman's Journal (June, 1860) said, "should be in the hands of women only." Miss Faithfull's experiments produced some considerable flutter amongst men. At first, the men looked down upon them with the contempt of traditional superiority; women compositors were "to die off like birds in winter" (cf. Printers' Journal, August 5th, 1867, where a correspondent stated that "the day is far distant when such labour can hope to supersede our own"); but some trepidation was speedily caused when it was found that women's shops were undercutting men's, and an alarmist article in the Printers' Register of February 6th, 1869, states that "the exertions of the advocates of female labour in the printing business have resulted in the establishment of a printing office where printing can be done on lower terms than those usually charged." That year Miss Faithfull was engaged in her libel action against Mr. Grant for calling her an atheist, and the Publishers' Circular furiously attacked her work. By-and-by, however, the controversy died down. Miss Faithfull's several attempts[9] to establish permanently a printing establishment bore fruit in the still existing Women's Printing Society, started in 1874.

[9] 1860, 1869, 1873; in 1869 another Women's Printing Office was started as a means of finding employment for educated ladies: Printers' Register, January 6th, 1869.

As an industrial factor, however, the "Women's Movement" has been altogether secondary, and women have been induced to enter the trades under review mainly because the subdivision of labour and the application of mechanical power had created simple processes; because they were willing to accept low wages; and because, unlike the men, who were members of Unions, they made no efforts to interfere in the management of the works.

Partly owing to the nature of the work done and partly to the power of the London Society of Compositors, no systematic attempt seems to have been made generally to introduce women compositors into London houses since 1878, and it is of some significance to note that most of the London firms which employed women compositors between 1873 and 1878—the period when the attempt was most actively made—have since disappeared, owing to bad equipment and the inferior character of their trade.

But the opposition to women lingered on after the attempts to introduce them more generally had ceased. In 1879 the London Society of Compositors decided that none of their members should finish work set up by women, and the firm of Messrs. Smyth and Yerworth was struck by the men's Union.[10]

[10] It is interesting to note that in these days also the women only set up the type and the men "made it up."

Commenting on this trouble, the Standard, in a leading article (October 8th, 1879) cynically remarked: "What women ask is not to be allowed to compete with men, which the more sensible among them know to be impossible, but to be allowed the chance of a small livelihood by doing the work of men a little cheaper than men care to do it. This is underselling of course, but it is difficult to see why, when all is said and done, men should object to be undersold by their own wives and daughters."