The Project Gutenberg EBook of Memoirs of Napoleon Bonaparte, Complete by Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Memoirs of Napoleon Bonaparte, Complete Author: Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne Release Date: September 3, 2006 [EBook #3567] Last updated: April 22, 2019 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MEMOIRS OF NAPOLEON *** Produced by David Widger

| PREFACE 1836 EDITION. | |

| PREFACE 1885 EDITION. | |

| AUTHOR'S INTRODUCTION. | |

| NOTE. | |

| VOLUME I. — 1769-1800 | |

| CHAPTER 1 | 1769-1783. Authentic date of Bonaparte's birth—His family ruined by the Jesuits—His taste for military amusements—Sham siege at the College of Brienne—The porter's wife and Napoleon—My intimacy with Bonaparte at college—His love for the mathematics, and his dislike of Latin—He defends Paoli and blames his father—He is ridiculed by his comrades—Ignorance of the monks—Distribution of prizes at Brienne—Madame de Montesson and the Duke of Orleans—Report of M. Keralio on Bonaparte—He leaves Brienne. |

| CHAPTER II. | 1784-1794. Bonaparte enters the Military College of Paris—He urges me to embrace the military profession—His report on the state of the Military School of Paris—He obtains a commission—I set off for Vienna—Return to Paris, where I again meet Bonaparte—His singular plans for raising money—Louis XVI, with the red cap on his head— The 10th of August—My departure for Stuttgart—Bonaparte goes to Corsica—My name inscribed on the list of emigrants—Bonaparte at the siege of Toulon—Le Souper de Beaucaire—Napoleon's mission to Genoa—His arrest—His autographical justification —Duroc's first connection with Bonaparte. |

| CHAPTER III. | 1794-1795. Proposal to send Bonaparte to La Vendée—He is struck off the list of general officers—Salicetti—Joseph's marriage with Mademoiselle Clary—Bonaparte's wish to go to Turkey—Note explaining the plan of his proposed expedition—Madame Bourrienne's character of Bonaparte, and account of her husband's arrest—Constitution of the year III— The 13th Vendemiaire—Bonaparte appointed second in command of the army of the interior—Eulogium of Bonaparte by Barras, and its consequences—St. Helena manuscript. |

| CHAPTER IV. | 1795-1797. On my return to Paris I meet Bonaparte—His interview with Josephine —Bonaparte's marriage, and departure from Paris ten days after— Portrait and character of Josephine—Bonaparte's dislike of national property—Letter to Josephine—Letter of General Colli, and Bonaparte's reply—Bonaparte refuses to serve with Kellerman— Marmont's letters—Bonaparte's order to me to join the army—My departure from Sens for Italy—Insurrection of the Venetian States. |

| CHAPTER V | 1797. Signature of the preliminaries of peace—Fall of Venice—My arrival and reception at Leoben—Bonaparte wishes to pursue his success— The Directory opposes him—He wishes to advance on Vienna—Movement of the army of the Sombre-et-Mouse—Bonaparte's dissatisfaction— Arrival at Milan—We take up our residence at Montebello—Napoleon's judgment respecting Dandolo and Melzi. |

| CHAPTER VI. | 1797. Napoleon's correspondence—Release of French prisoners at Olmutz— Negotiations with Austria—Bonaparte's dissatisfaction—Letter of complaint from Bonaparte to the Executive Directory—Note respecting the affairs of Venice and the Club of Clichy, written by Bonaparte and circulated in the army—Intercepted letter of the Emperor Francis. |

| CHAPTER VII. | 1797. Unfounded reports—Carnot—Capitulation of Mantua—General Clarke— The Directory yields to Bonaparte—Berthier—Arrival of Eugène Beauharnais at Milan—Comte Delannay d'Entraigues—His interview with Bonaparte—Seizure of his papers—Copy of one describing a conversation between him and Comte de Montgaillard—The Emperor Francis—The Prince de Condé and General Pichegru. |

| CHAPTER VIII. | 1797. The royalists of the interior—Bonaparte's intention of marching on Paris with 25,000 men—His animosity against the emigrants and the Clichy Club—His choice between the two parties of the Directory— Augereau's order of the day against the word 'Monsieur'—Bonaparte wishes to be made one of the five Directors—He supports the majority of the Directory—La Vallette, Augereau, and Bernadotte sent to Paris—Interesting correspondence relative to the 18th Fructidor. |

| CHAPTER IX. | 1797. Bonaparte's joy at the result of the 18th Fructidor.—His letter to Augereau—His correspondence with the Directory and proposed resignation—Explanation of the Directory—Bottot—General Clarke— Letter from Madame Bacciocchi to Bonaparte—Autograph letter of the Emperor Francis to Bonaparte—Arrival of Count Cobentzel—Autograph note of Bonaparte on the conditions of peace. |

| CHAPTER X. | 1797. Influence of the 18th Fructidor on the negotiations—Bonaparte's suspicion of Bottot—His complaints respecting the non-erasure of Bourrienne—Bourrienne's conversation with the Marquis of Gallo—Bottot writes from Paris to Bonaparte on the part of the Directory Agents of the Directory employed to watch Bonaparte—Influence of the weather on the conclusion of peace—Remarkable observation of Bonaparte—Conclusion of the treaty—The Directory dissatisfied with the terms of the peace—Bonaparte's predilection for representative government—Opinion on Bonaparte. |

| CHAPTER XI. | 1797 Effect of the 18th Fructidor on the peace—The standard of the army of Italy—Honours rendered to the memory of General Hoche and of Virgil at Mantua—Remarkable letter—In passing through Switzerland Bonaparte visits the field of Morat—Arrival at Rastadt—Letter from the Directory calling Bonaparte to Paris—Intrigues against Josephine—Grand ceremony on the reception of Bonaparte by the Directory—The theatres—Modesty of Bonaparte—An assassination—Bonaparte's opinion of the Parisians—His election to the National Institute—Letter to Camus—Projects—Reflections. |

| CHAPTER XII. | 1798. Bonaparte's departure from Paris—His return—The Egyptian expedition projected—M. de Talleyrand—General Desaix—Expedition against Malta—Money taken at Berne—Bonaparte's ideas respecting the East—Monge—Non-influence of the Directory—Marriages of Marmont and La Valette—Bonaparte's plan of colonising Egypt—His camp library—Orthographical blunders—Stock of wines—Bonaparte's arrival at Toulon—Madame Bonaparte's fall from a balcony—Execution of an old man—Simon. |

| CHAPTER XIII. | 1798. Departure of the squadron—Arrival at Malta—Dolomieu—General Barguay d'Hilliers—Attack on the western part of the island— Caffarelli's remark—Deliverance of the Turkish prisoners—Nelson's pursuit of the French fleet—Conversations on board—How Bonaparte passed his, time—Questions to the Captains—Propositions discussed —Morning music—Proclamation—Admiral Brueys—The English fleet avoided Dangerous landing—Bonaparte and his fortune—Alexandria taken—Kléber wounded—Bonaparte's entrance into Alexandria. |

| CHAPTER XIV. | 1798. The mirage—Skirmishes with the Arabs—Mistake of General Desaix's division—Wretchedness of a rich sheik—Combat beneath the General's window—The flotilla on the Nile—Its distress and danger—The battle of Chebreisse—Defeat of the Mamelukes—Bonaparte's reception of me—Letter to Louis Bonaparte—Success of the French army— Triumphal entrance into Cairo—Civil and military organisation of Cairo—Bonaparte's letter to his brother Joseph—Plan of colonisation. |

| CHAPTER XV. | 1798. Establishment of a divan in each Egyptian province—Desaix in Upper Egypt—Ibrahim Bey beaten by Bonaparte at Salehye'h—Sulkowsky wounded—Disaster at Aboukir—Dissatisfaction and murmurs of the army—Dejection of the General-in-Chief—His plan respecting Egypt —Meditated descent upon England—Bonaparte's censure of the Directory—Intercepted correspondence. |

| CHAPTER XVI. | 1798. The Egyptian Institute—Festival of the birth of Mahomet—Bonaparte's prudent respect for the Mahometan religion—His Turkish dress—Djezzar, the Pasha of Acre—Thoughts of a campaign in Germany—Want of news from France—Bonaparte and Madame Fourés—The Egyptian fortune-teller, M. Berthollet, and the Sheik El Bekri—The air "Marlbrook"—Insurrection in Cairo—Death of General Dupuis—Death of Sulkowsky—The insurrection quelled—Nocturnal executions—Destruction of a tribe of Arabs—Convoy of sick and wounded—Massacre of the French in Sicily—projected expedition to Syria—Letter to Tippoo Saib. |

| CHAPTER XVII. | 1798-1799. Bonaparte's departure for Suez—Crossing the desert—Passage of the Red Sea—The fountain of Moses—The Cenobites of Mount Sinai—Danger in recrossing the Red Sea—Napoleon's return to Cairo—Money borrowed at Genoa—New designs upon Syria—Dissatisfaction of the Ottoman Porte—Plan for invading Asia—Gigantic schemes—General Berthier's permission to return to France—His romantic love and the adored portrait—He gives up his permission to return home—Louis Bonaparte leaves Egypt—The first Cashmere shawl in France— Intercepted correspondence—Departure for Syria—Fountains of Messoudish—Bonaparte jealous—Discontent of the troops—El-Arish taken—Aspect of Syria—Ramleh—Jerusalem. |

| CHAPTER XVIII | 1799. Arrival at Jaffa—The siege—Beauharnais and Croisier—Four thousand prisoners—Scarcity of provisions—Councils of war—Dreadful necessity—The massacre—The plague—Lannes and the mountaineers— Barbarity of Djezarr—Arrival at St Jean d'Acre, and abortive attacks—Sir Sidney Smith—Death of Caffarelli—Duroc wounded— Rash bathing—Insurrections in Egypt. |

| CHAPTER XIX. | 1799. The siege of Acre raised—Attention to names in bulletins—Gigantic project—The Druses—Mount Carmel—The wounded and infected— Order to march on foot—Loss of our cannon—A Nablousian fires at Bonaparte—Return to Jaffa—Bonaparte visits the plague hospital—A potion given to the sick—Bonaparte's statement at St. Helena. |

| CHAPTER XX. | 1799. Murat and Moarad Bey at the Natron Lakes—Bonaparte's departure for the Pyramids—Sudden appearance of an Arab messenger—News of the landing of the Turks at Aboukir—Bonaparte marches against them—They are immediately attacked and destroyed in the battle of Aboukir—Interchange of communication with the English—Sudden determination to return to Europe—Outfit of two frigates— Bonaparte's dissimulation—His pretended journey to the Delta— Generous behaviour of Lanusee—Bonaparte's artifice—His bad treatment of General Kléber. |

| CHAPTER XXI | 1799. Our departure from Egypt—Nocturnal embarkation—M. Parseval Grandmaison—On course—Adverse winds—Fear of the English— Favourable weather—Vingt-et-un—Chess—We land at Ajaccio— Bonaparte's pretended relations—Family domains—Want of money— Battle of Novi—Death of Joubert—Visionary schemes—Purchase of a boat—Departure from Corsica—The English squadron—Our escape— The roads of Fréjus—Our landing in France—The plague or the Austrians—Joy of the people—The sanitary laws—Bonaparte falsely accused. |

| CHAPTER XXII. | 1799. Effect produced by Bonaparte's return—His justification— Melancholy letter to my wife—Bonaparte's intended dinner at Sens— Louis Bonaparte and Josephine—He changes his intended route— Melancholy situation of the provinces—Necessity of a change— Bonaparte's ambitious views—Influence of popular applause— Arrival in Paris—His reception of Josephine—Their reconciliation— Bonaparte's visit to the Directory—His contemptuous treatment of Sieyès. |

| CHAPTER XXIII | 1799. Moreau and Bernadotte—Bonaparte's opinion of Bernadotte—False report—The crown of Sweden and the Constitution of the year III.— Intrigues of Bonaparte's brothers—Angry conversation between Bonaparte and Bernadotte—Bonaparte's version—Josephine's version— An unexpected visit—The Manege Club—Salicetti and Joseph Bonaparte —Bonaparte invites himself to breakfast with Bernadotte—Country excursion—Bernadotte dines with Bonaparte—The plot and conspiracy —Conduct of Lucien—Dinner given to Bonaparte by the Council of the Five Hundred—Bonaparte's wish to be chosen a member of the Directory—His reconciliation with Sieyès—Offer made by the Directory to Bonaparte—He is falsely accused by Barras. |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | 1799. Cambacérès and Lebrun—Gohier deceived—My nocturnal visit to Barras —The command of the army given to Bonaparte—The morning of the 18th Brumaire—Meeting of the generals at Bonaparte's house— Bernadotte's firmness—Josephine's interest, for Madame Gohier— Disappointment of the Directors—Review in the gardens of the Tuileries—Bonaparte's harangue—Proclamation of the Ancients— Moreau, jailer of the Luxembourg—My conversation with La Vallette— Bonaparte at St. Cloud. |

| CHAPTER XXV. | 1799. The two Councils—Barras' letter—Bonaparte at the Council of the Five Hundred—False reports—Tumultuous sitting—Lucien's speech— He resigns the Presidency of the Council of the Five Hundred—He is carried out by grenadiers—He harangues the troops—A dramatic scene —Murat and his soldiers drive out the Five Hundred—Council of Thirty—Consular commission—Decree—Return to Paris—Conversation with Bonaparte and Josephine respecting Gohier and Bernadotte—The directors Gohier and Moulins imprisoned. |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | 1799. General approbation of the 18th Brumaire—Distress of the treasury— M. Collot's generosity—Bonaparte's ingratitude—Gohier set at Liberty—Constitution of the year VIII.—The Senate, Tribunate, and Council of State—Notes required on the character of candidates— Bonaparte's love of integrity and talent—Influence of habit over him—His hatred of the Tribunate—Provisional concessions—The first Consular Ministry—Mediocrity of La Place—Proscription lists— Cambacérès report—M. Moreau de Worms—Character of Sieyès— Bonaparte at the Luxembourg—Distribution of the day and visits— Lebrun's opposition—Bonaparte's singing—His boyish tricks— Assumption of the titles "Madame" and "Monseigneur"—The men of the Revolution and the partisans of the Bourbons—Bonaparte's fears— Confidential notes on candidates for office and the assemblies. |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | 1799-1800. Difficulties of a new Government—State of Europe—Bonaparte's wish for peace—M. de Talleyrand Minister for Foreign Affairs— Negotiations with England and Austria—Their failure—Bonaparte's views on the East—His sacrifices to policy—General Bonaparte denounced to the First Consul—Kléber's letter to the Directory— Accounts of the Egyptian expedition published in the Moniteur— Proclamation to the army of the East—Favour and disgrace of certain individuals accounted for. |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | 1800. Great and common men—Portrait of Bonaparte—The varied expression of his countenance—His convulsive shrug—Presentiment of his corpulency—Partiality for bathing—His temperance—His alleged capability of dispensing with sleep—Good and bad news—Shaving, and reading the journals—Morning business—Breakfast—Coffee and snuff —Bonaparte's idea of his own situation—His ill opinion of mankind —His dislike of a 'tête-à-tête'—His hatred of the Revolutionists —Ladies in white—Anecdotes—Bonaparte's tokens of kindness, and his droll compliments—His fits of ill humour—Sound of bells— Gardens of Malmaison—His opinion of medicine—His memory— His poetic insensibility—His want of gallantry—Cards and conversation—The dress-coat and black cravat—Bonaparte's payments —His religious ideas—His obstinacy. |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | 1800. Bonaparte's laws—Suppression of the festival of the 21st of January—Officials visits—The Temple—Louis XVI. and Sir Sidney Smith—Peculation during the Directory—Loan raised—Modest budget —The Consul and the Member of the Institute—The figure of the Republic—Duroc's missions—The King of Prussia—The Emperor Alexander—General Latour-Foissac—Arbitrary decree—Company of players for Egypt—Singular ideas respecting literary property— The preparatory Consulate—The journals—Sabres and muskets of honour—The First Consul and his Comrade—The bust of Brutus— Statues in the gallery of the Tuileries—Sections of the Council of State—Costumes of public functionaries—Masquerades—The opera-balls—Recall of the exiles. |

| CHAPTER XXX | 1800. Bonaparte and Paul I.—Lord Whitworth—Baron Sprengporten's arrival at Paris—Paul's admiration of Bonaparte—Their close connection and correspondence—The royal challenge—General Mack—The road to Malmaison—Attempts at assassination—Death of Washington—National mourning—Ambitious calculation—M. de Fontanel, the skilful orator —Fete at the Temple of Mars—Murat's marriage with Caroline Bonaparte—Madame Bonaparte's pearls. |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | 1800. Police on police—False information—Dexterity of Fouché—Police agents deceived—Money ill applied—Inutility of political police— Bonaparte's opinion—General considerations—My appointment to the Prefecture of police. |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | 1800. Successful management of parties—Precautions—Removal from the Luxembourg to the Tuileries—Hackney-coaches and the Consul's white horses—Royal custom and an inscription—The review—Bonaparte's homage to the standards—Talleyrand in Bonaparte's cabinet— Bonaparte's aversion to the cap of liberty even in painting—The state bed—Our cabinet. |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | 1800. The Tuileries—Royalty in perspective—Remarkable observation— Presentations—Assumption of the prerogative of mercy—M. Defeu— M. de Frotte—Georges Cadoudal's audience of Bonaparte—Rapp's precaution and Bonaparte's confidence—The dignity of France— Napper Tandy and Blackwell delivered up by the Senate of Hamburg— Contribution in the Egyptian style—Valueless bill—Fifteen thousand francs in the drawer of a secretaire—Josephine's debts—Evening walks with Bonaparte. |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | 1800. War and monuments—Influence of the recollections of Egypt— First improvements in Paris—Malmaison too little—St. Cloud taken —The Pont des Arts—Business prescribed for me by Bonaparte— Pecuniary remuneration—The First Consul's visit to the Pritanée— His examination of the pupils—Consular pensions—Tragical death of Miackzinski—Introduction of vaccination—Recall of the members of the Constituent Assembly—The "canary" volunteers—Tronchet and Target—Liberation of the Austrian prisoners—Longchamps and sacred music. |

| CHAPTER XXXV | 1800. The Memorial of St. Helena—Louis XVIII.'s first letter to Bonaparte —Josephine, Hortense, and the Faubourg St. Germain— Madame Bonaparte and the fortune-teller—Louis XVIII's second letter —Bonaparte's answer—Conversation respecting the recall of Louis XVIII.—Peace and war—A battle fought with pins—Genoa and Melas— Realisation of Bonaparte's military plans—Ironical letter to Berthier—Departure from Paris—Instructions to Lucien and Cambacérès—Joseph Bonaparte appointed Councillor of State— Travelling conversation—Alexander and Caesar judged by Bonaparte. |

| VOLUME II. —1800-1805 | |

| CHAPTER I. | 1800. Bonaparte's confidence in the army—'Ma belle' France—The convent of Bernadins—Passage of Mont St. Bernard—Arrival at the convent— Refreshments distributed to the soldiers—Mont Albaredo—Artillery dismounted—The fort of Bard—Fortunate temerity—Bonaparte and Melas—The spy—Bonaparte's opinion of M. Necker—Capitulation of Genoa—Intercepted despatch—Lannes at Montebello—Boudet succeeded by Desaix—Coolness of the First Consul to M. Collot—Conversation and recollections—The battle of Marengo—General Kellerman—Supper sent from the Convent del Bosco—Particulars respecting the death of Desaix—The Prince of Lichtenstein—Return to Milan—Savary and Rapp. |

| CHAPTER II. | 1800. Suspension of hostilities—Letter to the Consuls—Second Occupation of Milan—Bonaparte and Massena—Public acclamations and the voice of Josephine—Stray recollections—Organization of Piedmont—Sabres of honour—Rewards to the army of the Rhine—Pretended army of reserve—General Zach—Anniversary of the 14th of July—Monument to Desaix—Desaix and Foy—Bonaparte's speech in the Temple of Mars— Arrival of the Consular Guard—The bones of marshal Turenne— Lucien's successful speech—Letter from Lucien to Joseph Bonaparte— The First Consul's return to Paris—Accidents on the road— Difficulty of gaining lasting fame—Assassination of Kléber— Situation of the terrace on which Kléber was stabbed—Odious rumours —Arrival of a courier—A night scene—Bonaparte's distress on perusing the despatches from Egypt. |

| CHAPTER III. | 1800. Bonaparte's wish to negotiate with England and Austria— An emigrant's letter—Domestic details—The bell—Conspiracy of Ceracchi, Arena, Harrel, and others—Bonaparte's visit to the opera —Arrests—Rariel appointed commandant of Vincennes—The Duc d'Enghien's foster-sister—The 3d Nivoise—First performance of Haydn's "Creation"—The infernal machine—Congratulatory addresses— Arbitrary condemnations—M. Tissot erased from the list of the banished—M. Truguet—Bonapartes' hatred of the Jacobins explained— The real criminals discovered—Justification of Fouché—Execution of St. Regent and Carbon—Caesar, Cromwell, and Bonaparte—Conversation between Bonaparte and Fouché—Pretended anger—Fouché's dissimulation—Lucien's resignation—His embassy to Spain—War between Spain and Portugal—Dinner at Fouché's—Treachery of Joseph Bonaparte—A trick upon the First Consul—A three days' coolness— Reconciliation. |

| CHAPTER IV. | 1800-1801 Austria bribed by England—M. de St. Julien in Paris—Duroc's mission—Rupture of the armistice—Surrender of three garrisons— M. Otto in London—Battle of Hohenlinden—Madame Moreau and Madame Hulot—Bonaparte's ill-treatment of the latter—Congress of Luneville—General Clarke—M. Maret—Peace between France and Austria—Joseph Bonaparte's speculations in the funds— M. de Talleyrand's advice—Post-office regulation—Cambacérès— Importance of good dinners in the affairs of Government—Steamboats and intriguers—Death of Paul I.—New thoughts of the reestablishment of Poland—Duroc at St. Petersburg—Bribe rejected— Death of Abercromby. |

| CHAPTER V. | 1801-1802. An experiment of royalty—Louis de Bourbon and Maria Louisa, of Spain—Creation of the kingdom of Etruria—The Count of Leghorn in Paris—Entertainments given him—Bonaparte's opinion of the King of Etruria—His departure for Florence, and bad reception there— Negotiations with the Pope—Bonaparte's opinion on religion—Te Deum at Notre Dame—Behaviour of the people in the church—Irreligion of the Consular Court—Augereau's remark on the Te Deum—First Mass at St. Cloud-Mass in Bonaparte's apartments—Talleyrand relieved from his clerical vows—My appointment to the Council of State. |

| CHAPTER VI. | 1802. Last chapter on Egypt—Admiral Gantheaume—Way to please Bonaparte— General Menou's flattery and his reward—Davoust—Bonaparte regrets giving the command to Menou, who is defeated by Abercromby—Otto's negotiation in London—Preliminaries of peace. |

| CHAPTER VII. | 1802. The most glorious epoch for France—The First Consul's desire of peace—Malta ceded and kept—Bonaparte and the English journals— Mr. Addington's letter to the First Consul—Bonaparte prosecutes Peltier—Leclerc's expedition to St. Domingo—Toussaint Louverture— Death of Leclerc—Rochambeau, his successor, abandons St. Domingo— First symptoms of Bonaparte's malady—Josephine's intrigues for the marriage of Hortense—Falsehood contradicted. |

| CHAPTER VIII. | 1802-1803. Bonaparte President of the Cisalpine Republic—Meeting of the deputation at Lyons—Malta and the English—My immortality—Fete given by Madame Murat—Erasures from the emigrant list—Restitution of property—General Sebastiani—Lord Whitworth—Napoleon's first symptoms of disease—Corvisart—Influence of physical suffering on Napoleon's temper—Articles for the Moniteur—General Andreossi— M. Talleyrand's pun—Jerome Bonaparte—Extravagance of Bonaparte's brothers—M. Collot and the navy contract. |

| CHAPTER IX. | 1802. Proverbial falsehood of bulletins—M. Doublet—Creation of the Legion of Honour—Opposition to it in the Council and other authorities of the State—The partisans of an hereditary system— The question of the Consulship for life. |

| CHAPTER X. | 1802. General Bernadotte pacifies La vendee and suppresses a mutiny at Tours—Bonaparte's injustice towards him—A premeditated scene— Advice given to Bernadotte, and Bonaparte disappointed—The First Consul's residence at St. Cloud—His rehearsals for the Empire— His contempt of mankind—Mr. Fox and Bonaparte—Information of plans of assassination—A military dinner given by Bonaparte—Moreau not of the party—Effect of the 'Senates-consultes' on the Consulate for life—Journey to Plombieres—Previous scene between Lucien and Josephine—Theatrical representations at Neuilly and Malmaison— Loss of a watch, and honesty rewarded—Canova at St. Cloud— Bonaparte's reluctance to stand for a model. |

| CHAPTER XI. | 1802. Bonaparte's principle as to the change of Ministers—Fouché—His influence with the First Consul—Fouché's dismissal—The departments of Police and Justice united under Regnier—Madame Bonaparte's regret for the dismissal of Fouché—Family scenes—Madame Louis Bonaparte's pregnancy—False and infamous reports to Josephine— Legitimacy and a bastard—Raederer reproached by Josephine—Her visit to Ruel—Long conversation with her—Assertion at St. Helena respecting a great political fraud. |

| CHAPTER XII. | 1802. Citizen Fesch created Cardinal Fesch—Arts and industry—Exhibition in the Louvre—Aspect of Paris in 1802—The Medicean Venus and the Velletrian Pallas—Signs of general prosperity—Rise of the funds— Irresponsible Ministers—The Bourbons—The military Government— Annoying familiarity of Lannes—Plan laid for his disgrace— Indignation of Lannes—His embassy to Portugal—The delayed despatch—Bonaparte's rage—I resign my situation—Duroc— I breakfast with Bonaparte—Duroc's intercession—Temporary reconciliation. |

| CHAPTER XIII. | 1802-1803. The Concordat and the Legion of Honour—The Council of State and the Tribunate—Discussion on the word 'subjects'—Chenier—Chabot de l'Allier's proposition to the Tribunate—The marked proof of national gratitude—Bonaparte's duplicity and self-command—Reply to the 'Senatus-consulte'—The people consulted—Consular decree— The most, or the least—M. de Vanblanc's speech—Bonaparte's reply— The address of the Tribunate—Hopes and predictions thwarted. |

| CHAPTER XIV | 1802-1803. Departure for Malmaison—Unexpected question relative to the Bourbons—Distinction between two opposition parties—New intrigues of Lucien—Camille Jordan's pamphlet seized—Vituperation against the liberty of the press—Revisal of the Constitution—New 'Senatus-consulte—Deputation from the Senate—Audience of the Diplomatic Body—Josephine's melancholy—The discontented—Secret meetings—Fouché and the police agents—The Code Napoleon— Bonaparte's regular attendance at the Council of State—His knowledge of mankind, and the science of government—Napoleon's first sovereign act—His visit to the Senate—The Consular procession—Polite etiquette—The Senate and the Council of State— Complaints against Lucien—The deaf and dumb assembly—Creation of senatorships. |

| CHAPTER XV | 1802. The intoxication of great men—Unlucky zeal—MM. Maret, Champagny, and Savary—M. de Talleyrand's real services—Postponement of the execution of orders—Fouché and the Revolution—The Royalist committee—The charter first planned during the Consulate—Mission to Coblentz—Influence of the Royalists upon Josephine—The statue and the pedestal—Madame de Genlis' romance of Madame de la Valliere—The Legion of Honour and the carnations—Influence of the Faubourg St. Germain—Inconsiderate step taken by Bonaparte—Louis XVIII's indignation—Prudent advice of the Abbe Andre—Letter from Louis XVIII. to Bonaparte—Council held at Neuilly—The letter delivered—Indifference of Bonaparte, and satisfaction of the Royalists. |

| CHAPTER XVI | 1802. The day after my disgrace—Renewal of my duties—Bonaparte's affected regard for me—Offer of an assistant—M. de Meneval—My second rupture with Bonaparte—The Duc de Rovigo's account of it— Letter from M. de Barbe Marbois—Real causes of my separation from the First Consul—Postscript to the letter of M. de Barbe Marbois— The black cabinet—Inspection of letters dining the Consulate— I retire to St. Cloud—Communications from M. de Meneval—A week's conflict between friendship and pride—My formal dismissal—Petty revenge—My request to visit England—Monosyllabic answer—Wrong suspicion—Burial of my papers—Communication from Duroc—My letter to the First Consul—The truth acknowledged. |

| CHAPTER XVII. | 1803. The First Consul's presentiments respecting the duration of peace— England's uneasiness at the prosperity of France—Bonaparte's real wish for war—Concourse of foreigners in Paris—Bad faith of England—Bonaparte and Lord Whitworth—Relative position of France and England-Bonaparte's journey to the seaboard departments— Breakfast at Compiegne—Father Berton—Irritation excited by the presence of Bouquet—Father Berton's derangement and death—Rapp ordered to send for me—Order countermanded. |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | 1803. Vast works undertaken—The French and the Roman soldiers—Itinerary of Bonaparte's journeys to the coast—Twelve hours on horseback— Discussions in Council—Opposition of Truguet—Bonaparte'a opinion on the point under discussion—Two divisions of the world—Europe a province—Bonaparte's jealousy of the dignity of France—The Englishman in the dockyard of Brest—Public audience at the Tuilleries—The First Consul's remarks upon England—His wish to enjoy the good opinion of the English people—Ball at Malmaison— Lines on Hortense's dancing—Singular motive for giving the ball. |

| CHAPTER XIX. | 1803. Mr. Pitt—Motive of his going out of office—Error of the English Government—Pretended regard for the Bourbons—Violation of the treaty of Amiens—Reciprocal accusations—Malta—Lord Whitworth's departure—Rome and Carthage—Secret satisfaction of Bonaparte— Message to the Senate, the Legislative Body, and the Tribunate— The King of England's renunciation of the title of King of France— Complaints of the English Government—French agents in British ports —Views of France upon Turkey—Observation made by Bonaparte to the Legislative Body—Its false interpretation—Conquest of Hanover— The Duke of Cambridge caricatured—The King of England and the Elector of Hanover—First address to the clergy—Use of the word "Monsieur"—The Republican weeks and months. |

| CHAPTER XX. | 1803. Presentation of Prince Borghese to Bonaparte—Departure for Belgium Revival of a royal custom—The swans of Amiens—Change of formula in the acts of Government—Company of performers in Bonaparte's suite—Revival of old customs—Division of the institute into four classes—Science and literature—Bonaparte's hatred of literary men —Ducis—Bernardin de Saint-Pierre—Chenier and Lemercier— Explanation of Bonaparte's aversion to literature—Lalande and his dictionary—Education in the hands of Government—M. de Roquelaure, Archbishop of Malines. |

| CHAPTER XXI. | 1804. The Temple—The intrigues of Europe—Prelude to the Continental system—Bombardment of Granville—My conversation with the First Consul on the projected invasion of England—Fauche Borel—Moreau and Pichegru—Fouché's manoeuvres—The Abbe David and Lajolais— Fouché's visit to St. Cloud—Regnier outwitted by Fouché— My interview with the First Consul—His indignation at the reports respecting Hortense—Contradiction of these calumnies—The brothers Faucher—Their execution—The First Consul's levee—My conversation with Duroc—Conspiracy of Georges, Moreau, and Pichegru—Moreau averse to the restoration of the Bourbons—Bouvet de Lozier's attempted suicide—Arrest of Moreau—Declaration of MM. de Polignac and de Riviere—Connivance of the police—Arrest of M. Carbonnet and his nephew. |

| CHAPTER XXII. | 1804. The events of 1804—Death of the Duc d'Enghien—Napoleon's arguments at St. Helena—Comparison of dates—Possibility of my having saved the Duc d'Enghien's life—Advice given to the Duc d'Enghien—Sir Charles Stuart—Delay of the Austrian Cabinet—Pichegru and the mysterious being—M. Massias—The historians of St. Helena— Bonaparte's threats against the emigrants and M. Cobentzel— Singular adventure of Davoust's secretary—The quartermaster— The brigand of La Vendée. |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | 1804. General Ordener's mission—Arrest of the Duc d'Enghien—Horrible night-scene—-Harrel's account of the death of the Prince—Order for digging the grave—The foster-sister of the Duc d'Enghien—Reading the sentence—The lantern—General Savary—The faithful dog and the police—My visit to Malmaison—Josephine's grief— The Duc d'Enghien's portrait and lock of hair—Savary's emotion— M. de Chateaubriand's resignation—M. de Chateaubriand's connection with Bonaparte—Madame Bacciocchi and M. de Fontanes—Cardinal Fesch —Dedication of the second edition of the 'Genie du Christianisme' —M. de Chateaubriand's visit to the First Consul on the morning of the Duc d'Enghien's death—Consequences of the Duc d'Enghien's death—Change of opinion in the provinces—The Gentry of the Chateaus—Effect of the Duc d'Enghien's death on foreign Courts— Remarkable words of Mr. Pitt—Louis XVIII. sends back the insignia of the Golden Fleece to the King of Spain. |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | 1804. Pichegru betrayed—His arrest—His conduct to his old aide de camp— Account of Pichegru's family, and his education at Brienne— Permission to visit M. Carbonnet—The prisoners in the Temple— Absurd application of the word "brigand"—Moreau and the state of public opinion respecting him—Pichegru's firmness—Pichegru strangled in prison—Public opinion at the time—Report on the death of Pichegru. |

| CHAPTER XXV. | 1804. Arrest of Georges—The fruiterer's daughter of the Rue de La Montagne—St. Genevieve—Louis Bonaparte's visit to the Temple— General Lauriston—Arrest of Villeneuve and Barco—Villeneuve wounded—Moreau during his imprisonment—Preparations for leaving the Temple—Remarkable change in Georges—Addresses and congratulations—Speech of the First Consul forgotten—Secret negotiations with the Senate—Official proposition of Bonaparte's elevation to the Empire—Sitting of the Council of State— Interference of Bonaparte—Individual votes—Seven against twenty— His subjects and his people—Appropriateness of the title of Emperor—Communications between Bonaparte and the Senate—Bonaparte first called Sire by Cambacérès—First letter signed by Napoleon as Emperor—Grand levee at the Tuileries—Napoleon's address to the Imperial Guard—Organic 'Senatus-consulte'—Revival of old formulas and titles—The Republicanism of Lucien—The Spanish Princess— Lucien's clandestine marriage—Bonaparte's influence on the German Princes—Intrigues of England—Drake at Munich—Project for overthrowing Bonaparte's Government—Circular from the Minister for Foreign Affairs to the members of the Diplomatic Body—Answers to that circular. |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | 1804. Trial of Moreau, Georges, and others—Public interest excited by Moreau—Arraignment of the prisoners—Moreau's letter to Bonaparte— Violence of the President of the Court towards the prisoners— Lajolais and Rolland—Examinations intended to criminate Moreau— Remarkable observations—Speech written by M. Garat—Bonaparte's opinion of Garat's eloquence—General Lecourbe and Moreau's son— Respect shown to Moreau by the military—Different sentiments excited by Georges and Moreau—Thoriot and 'Tui-roi'—Georges' answers to the interrogatories—He refuses an offer of pardon— Coster St. Victor—Napoleon and an actress—Captain Wright— M. de Riviere and the medal of the Comte d'Artois—Generous struggle between MM. de Polignac—Sentence on the prisoners—Bonaparte's remark—Pardons and executions. |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | 1804. Clavier and Hemart—Singular Proposal of Corvisart-M. Desmaisons— Project of influencing the judges—Visit to the Tuileries—Rapp in attendance—Long conversation with the Emperor—His opinion on the trial of Moreau—English assassins and Mr. Fox—Complaints against the English Government—Bonaparte and Lacuee—Affectionate behaviour—Arrest of Pichegru—Method employed by the First Consul to discover his presence in Paris—Character of Moreau—Measures of Bonaparte regarding him—Lauriston sent to the Temple—Silence respecting the Duc d'Enghien—Napoleon's opinion of Moreau and Georges—Admiration of Georges—Offers of employment and dismissal— Recital of former vexations—Audience of the Empress—Melancholy forebodings—What Bonaparte said concerning himself—Marks of kindness. |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | 1804. Curious disclosures of Fouché—Remarkable words of Bonaparte respecting the protest of Louis XVIII—Secret document inserted in the Moniteur—Announcement from Bonaparte to Regnier—Fouché appointed Minister of Police—Error of Regnier respecting the conspiracy of Georges—Undeserved praise bestowed on Fouché— Indication of the return of the Bourbons—Variation between the words and conduct of Bonaparte—The iron crown—Celebration of the 14th of July—Church festivals and loss of time—Grand ceremonial at the Invalides—Recollections of the 18th Brumaire—New oath of the Legion of Honour—General enthusiasm—Departure for Boulogne—Visits to Josephine at St. Cloud and Malmaison—Josephine and Madame de Rémusat—Pardons granted by the Emperor—Anniversary of the 14th of July—Departure for the camp of Boulogne—General error respecting Napoleon's designs—Caesar's Tower—Distribution of the crosses of the Legion of Honour—The military throne—Bonaparte's charlatanism —Intrepidity of two English sailors—The decennial prizes and the Polytechnic School—Meeting of the Emperor and Empress—First negotiation with the Holy Sea—The Prefect of Arras and Comte Louis de Narbonne—Change in the French Ministry. |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | 1804. England deceived by Napoleon—Admirals Missiessy and Villeneuve— Command given to Lauriston—Napoleon's opinion of Madame de Stael— Her letters to Napoleon—Her enthusiasm converted into hatred— Bonaparte's opinion of the power of the Church—The Pope's arrival at Fontainebleau—Napoleon's first interview with Pius VII.— The Pope and the Emperor on a footing of equality—Honours rendered to the Pope—His apartments at the Tuileries—His visit to the Imperial printing office—Paternal rebuke—Effect produced in England by the Pope's presence in Paris—Preparations for Napoleon's coronation—Votes in favour of hereditary succession—Convocation of the Legislative Body—The presidents of cantons—Anecdote related by Michot the actor—Comparisons—Influence of the Coronation on the trade of Paris—The insignia of Napoleon and the insignia of Charlemagne—The Pope's mule—Anecdote of the notary Raguideau— Distribution of eagles in the Champ de Mars—Remarkable coincidence. |

| CHAPTER XXX. | 1805 My appointment as Minister Plenipotentiary at Hamburg—My interview with Bonaparte at Malmaison—Bonaparte's designs respecting Italy— His wish to revisit Brienne—Instructions for my residence in Hamburg—Regeneration of European society—Bonaparte's plan of making himself the oldest sovereign in Europe—Amedee Jaubert's mission—Commission from the Emperor to the Empress—My conversation with Madame Bonaparte. |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | 1805 Napoleon and Voltaire—Demands of the Holy See—Coolness between the pope and the Emperor—Napoleon's departure for Italy—Last interview between the Pope and the Emperor at Turin—Alessandria—The field of Marengo—The last Doge of Genoa—Bonaparte's arrival at Milan—Union of Genoa to the French Empire—Error in the Memorial of St. Helen— Bonaparte and Madam Grassini—Symptoms of dissatisfaction on the part of Austria and Russia—Napoleon's departure from Milan— Monument to commemorate the battle of Marengo—Napoleon's arrival in Paris and departure for Boulogne—Unfortunate result of a naval engagement—My visit to Fouché's country seat—Sieyès, Barras, the Bourbons, and Bonaparte—Observations respecting Josephine. |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | 1805. Capitulation of Sublingen—Preparations for war—Utility of commercial information—My instructions—Inspection of the emigrants and the journals—A pamphlet by Kotzebue—Offers from the Emperor of Russia to Moreau—Portrait of Gustavus Adolphus by one of his ministers—Fouché's denunciations—Duels at Hamburg—M. de Gimel —The Hamburg Correspondent—Letter from Bernadotte. |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | 1805. Treaty of alliance between England and Russia—Certainty of an approaching war—M. Forshmann, the Russian Minister—Duroc's mission to Berlin—New project of the King of Sweden—Secret mission to the Baltic—Animosity against France—Fall of the exchange between Hamburg and Paris—Destruction of the first Austrian army—Taking of Ulm—The Emperor's displeasure at the remark of a soldier—Battle of Trafalgar—Duroc's position at the Court of Prussia—Armaments in Russia—Libel upon Napoleon in the Hamburg 'Corespondent'— Embarrassment of the Syndic and Burgomaster of Hamburg—The conduct of the Russian Minister censured by the Swedish and English Ministers. |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | 1805 Difficulties of my situation at Hamburg—Toil and responsibility— Supervision of the emigrants—Foreign Ministers—Journals—Packet from Strasburg—Bonaparte fond of narrating Giulio, an extempore recitation of a story composed by the Emperor. |

| VOLUME III. — 1805-1814 | |

| CHAPTER I. | 1805. Abolition of the Republican calendar—Warlike preparations in Austria—Plan for re-organizing the National Guard—Napoleon in Strasburg—General Mack—Proclamation—Captain Bernard's reconnoitering mission—The Emperor's pretended anger and real satisfaction—Information respecting Ragusa communicated by Bernard —Rapid and deserved promotion—General Bernard's retirement to the United States of America. |

| CHAPTER II. | 1805. Rapidity of Napoleon's victories—Murat at Wertingen—Conquest of Ney's duchy—The French army before Ulm—The Prince of Liechtenstein at the Imperial headquarters—His interview with Napoleon described by Rapp—Capitulation of Ulm signed by Berthier and Mack—Napoleon before and after a victory—His address to the captive generals— The Emperor's proclamation—Ten thousand prisoners taken by Murat— Battle of Caldiero in Italy—Letter from Duroc—Attempts to retard the Emperor's progress—Fruitless mission of M. de Giulay—The first French eagles taken by the Russians—Bold adventure of Lannes and Murat—The French enter Vienna—Savary's mission to the Emperor Alexander. |

| CHAPTER III. | 1805. My functions at Hamburg—The King of Sweden at Stralsund— My bulletin describing the situation of the Russian armies—Duroc's recall from Berlin—General Dumouriez—Recruiting of the English in Hanover—The daughter of M. de Marbeof and Napoleon—Treachery of the King of Naples—The Sun of Austerlitz—Prince Dolgiorouki Rapp's account of the battle of Austerlitz—Gerard's picture— Eugène's marriage. |

| CHAPTER IV. | 1805. Depreciation of the Bank paper—Ouvrard—His great discretion— Bonaparte's opinion of the rich—Ouvrard's imprisonment—His partnership with the King of Spain—His connection with Waalenberghe and Desprez—Bonaparte's return to Paris after the campaign of Vienna—Hasty dismissal of M. Barbe Marbois. |

| CHAPTER V | 1805-1806. Declaration of Louis XVIII.—Dumouriez watched—News of a spy— Remarkable trait of courage and presence of mind—Necessity of vigilance at Hamburg—The King of Sweden—His bulletins—Doctor Gall —Prussia covets Hamburg—Projects on Holland—Negotiations for peace—Mr. Fox at the head of the British Cabinet—Intended assassination of Napoleon—Propositions made through Lord Yarmouth —Proposed protection of the Hanse towns—Their state— Aggrandisement of the Imperial family—Neither peace nor war— Sebastiani's mission to Constantinople—Lord Lauderdale at Paris, and failure of the negotiations—Austria despoiled—Emigrant pensions—Dumouriez's intrigues—Prince of Mecklenburg-Schwerin— Loizeau. |

| CHAPTER VI. | 1806. Menaces of Prussia—Offer for restoring Hanover to England—Insolent ultimatum—Commencement of hostilities between France and Prussia— Battle of Auerstadt—Death of the Duke of Brunswick—Bernadotte in Hamburg—Davonet and Bernadotte—The Swedes at Lübeck—Major Amiel— Service rendered to the English Minister at Hamburg—My appointment of Minister for the King of Naples—New regulation of the German post-office—The Confederation of the North—Devices of the Hanse Towns—Occupation of Hamburg in the name of the Emperor—Decree of Berlin—The military governors of Hamburg—Brune, Michaud, and Bernadotte. |

| CHAPTER VII. | 1806. Ukase of the Emperor of Russia—Duroc's mission to Weimar— Napoleon's views defeated—Triumphs of the French armies—Letters from Murat—False report respecting Murat—Resemblance between Moreau and M. Billand—Generous conduct of Napoleon—His interview with Madame Hatzfeld at Berlin—Letter from Bonaparte to Josephine— Blücher my prisoner—His character—His confidence in the future fate of Germany—Prince Paul of Wurtemberg taken prisoner—His wish to enter the French service—Distinguished emigrants at Altona— Deputation of the Senate to the Emperor at Berlin—The German Princes at Altona—Fauche-Boiel and the Comte de Gimel. |

| CHAPTER VIII. | 1806. Alarm of the city of Hamburg—The French at Bergdorf—Favourable orders issued by Bernadotte—Extortions in Prussia—False endorsements—Exactions of the Dutch—Napoleon's concern for his wounded troops—Duroc's mission to the King of Prussia—Rejection of the Emperor's demands—My negotiations at Hamburg—Displeasure of the King of Sweden—M. Netzel and M. Wetteratedt. |

| CHAPTER IX. | 1806 The Continental system—General indignation excited by it—Sale of licences by the French Government—Custom-house system at Hamburg— My letter to the Emperor—Cause of the rupture with Russia— Bernadotte's visit to me—Trial by court-martial for the purchase of a sugar-loaf—Davoust and the captain "rapporteur"—Influence of the Continental system on Napoleon's fall. |

| CHAPTER X. | 1806-1807. New system of war—Winter quarters—The Emperor's Proclamation— Necessity of marching to meet the Russians—Distress in the Hanse Towns—Order for 50,000 cloaks—Seizure of Russian corn and timber— Murat's entrance into Warsaw—Re-establishment of Poland—Duroc's accident—M. de Talleyrand's carriage stopped by the mud—Napoleon's power of rousing the spirit of his troops—His mode of dictating— The Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin—His visits to Hamburg—The Duke of Weimar—His letter and present—Journey of the Hereditary Prince of Denmark to Paris—Batter, the English spy—Traveling clerks—Louis Bonaparte and the Berlin decree—Creation of the Kingdom of Saxony— Veneration of Germany for the King of Saxony—The Emperor's uncertainty respecting Poland—Fetes and reviews at Warsaw—The French Government at the Emperor's head quarters—Ministerial portfolios sent to Warsaw.—Military preparations during the month of January—Difference of our situation daring the campaigns of Vienna and Prussia—News received and sent—Conduct of the Cabinet of Austria similar to that of the Cabinet of Berlin—Battle of Eylau—Unjust accusation against Bernadotte—Death of General d'Hautpoult—Te Deum chanted by the Russians—Gardanne's mission to Persia |

| CHAPTER XI. | 1807 Abuse of military power—Defence of diplomatic rights—Marshal Brune —Army supplies—English cloth and leather—Arrest on a charge of libel—Dispatch from M. Talleyrand—A page of Napoleon's glory— Interview between the two Emperors at Tilsit,—Silesia restored to the Queen of Prussia—Unfortunate situation in Prussia— Impossibility of reestablishing Poland in 1807—Foundation of the Kingdom of Westphalia—The Duchy of Warsaw and the King of Saxony. |

| CHAPTER XII. | 1807. Effect produced at Altona by the Treaty of Tilsit—The Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin's departure from Hamburg—English squadron in the Sound—Bombardment of Copenhagen—Perfidy of England—Remark of Bonaparte to M. Lemercier—Prussia erased from the map—Napoleon's return to Paris—Suppression of the Tribunate—Confiscation of English merchandise—Nine millions gained to France—M. Caulaincourt Ambassador to Russia—Repugnance of England to the intervention of Russia—Affairs of Portugal—Junot appointed to command the army— The Prince Regent's departure for the Brazils—The Code Napoleon— Introduction of the French laws into Germany—Leniency of Hamburg Juries—The stolen cloak and the Syndic Doormann. |

| CHAPTER XIII. | 1807-1808. Disturbed state of Spain—Godoy, Prince of the Peace—Reciprocal accusations between the King of Spain and his son—False promise of Napoleon—Dissatisfaction occasioned by the presence of the French troops—Abdication of Charles IV.—The Prince of the Peace made prisoner—Murat at Madrid—Important news transmitted by a commercial letter—Murat's ambition—His protection of Godoy— Charles IV, denies his voluntary abdication—The crown of Spain destined for Joseph—General disapprobation of Napoleon's conduct— The Bourbon cause apparently lost—Louis XVIII. after his departure from France—As Comte de Provence at Coblentz—He seeks refuge in Turin and Verona—Death of Louis XVII—Louis XVIII. refused an asylum in Austria, Saxony, and Prussia—His residence at Mittan and Warsaw—Alexander and Louis XVIII—The King's departure from Milan and arrival at Yarmouth—Determination of the King of England—M. Lemercier's prophecy to Bonaparte—Fouché's inquiries respecting Comte de Rechteren—Note from Josephine—New demands on the Hanse Towns—Order to raise 3000 sailors in Hamburg. |

| CHAPTER XIV. | 1808. Departure of the Prince of Ponte-Corvo—Prediction and superstition —Stoppage of letters addressed to the Spanish troops—La Romana and Romanillos—Illegible notifications—Eagerness of the German Princes to join the Confederation of the Rhine—Attack upon me on account of M. Hue—Bernadotte's successor in Hamburg—Exactions and tyrannical conduct of General Dupas—Disturbance in Hamburg—Plates broken in a fit of rage—My letter to Bernadotte—His reply—Bernadotte's return to Hamburg, and departure of Dupas for Lübeck—Noble conduct of the 'aide de camp' Barrel. |

| CHAPTER XV. | 1808. Promulgation of the Code of Commerce—Conquests by Status-consulte— Three events in one day—Recollections—Application of a line of Voltaire—Creation of the Imperial nobility—Restoration of the university—Aggrandisement of the kingdom of Italy at the expense of Rome—Cardinal Caprara'a departure from Paris—The interview at Erfurt. |

| CHAPTER XVI. | 1808. The Spanish troops in Hamburg—Romana's siesta—His departure for Funen—Celebration of Napoleon's birthday—Romana's defection— English agents and the Dutch troops—Facility of communication between England and the Continent—Delay of couriers from Russia— Alarm and complaints—The people of Hamburg—Montesquieu and the Minister of the Grand Duke of Tuscany—Invitations at six months— Napoleon's journey to Italy—Adoption of Eugène—Lucien's daughter and the Prince of the Asturias—M. Auguste de Stael's interview with Napoleon. |

| CHAPTER XVII. | 1808. The Republic of Batavia—The crown of Holland offered to Louis— Offer and refusal of the crown of Spain—Napoleon's attempt to get possession of Brabant—Napoleon before and after Erfart— A remarkable letter to Louis—Louis summoned to Paris—His honesty and courage—His bold language—Louis' return to Holland, and his letter to Napoleon—Harsh letter from Napoleon to Louis—Affray at Amsterdam—Napoleon's displeasure and last letter to his brother— Louis' abdication in favour of his son—Union of Holland to the French Empire—Protest of Louis against that measure—Letter from M. Otto to Louis. |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | 1809. Demands for contingents from some of the small States of Germany— M. Metternich—Position of Russia with respect to France—Union of Austria and Russia—Return of the English to Spain—Soult King of Portugal, and Murat successor to the Emperor—First levy of the landwehr in Austria—Agents of the Hamburg 'Correspondent'— Declaration of Prince Charles—Napoleon's march to Germany—His proclamation—Bernadotte's departure for the army—Napoleon's dislike of Bernadotte—Prince Charles' plan of campaign—The English at Cuxhaven—Fruitlessness of the plots of England—Napoleon wounded—Napoleon's prediction realised—Major Schill—Hamburg threatened and saved—Schill in Lübeck—His death, and destruction of his band—Schill imitated by the Duke of Brunswick-Oels— Departure of the English from Cuxhaven. |

| CHAPTER XIX. | 1809. The castle of Diernstein—Richard Coeur de Lion and Marshal Lannes, —The Emperor at the gates of Vienna—The Archduchess Maria Louisa— Facility of correspondence with England—Smuggling in Hamburg—Brown sugar and sand—Hearses filled with sugar and coffee—Embargo on the publication of news—Supervision of the 'Hamburg Correspondant'— Festival of Saint Napoleon—Ecclesiastical adulation—The King of Westphalia's journey through his States—Attempt to raise a loan— Jerome's present to me—The present returned—Bonaparte's unfounded suspicions. |

| CHAPTER XX. | 1809. Visit to the field of Wagram.—Marshal Macdonald—Union of the Papal States with the Empire—The battle of Talavera—Sir Arthur Wellesley—English expedition to Holland—Attempt to assassinate the Emperor at Schoenbrunn—Staps Interrogated by Napoleon—Pardon offered and rejected—Fanaticism and patriotism—Corvisart's examination of Staps—Second interrogatory—Tirade against the illuminati—Accusation of the Courts of Berlin and Weimar—Firmness and resignation of Staps—Particulars respecting his death— Influence of the attempt of Staps on the conclusion of peace— M. de Champagny. |

| CHAPTER XXI. | 1809. The Princess Royal of Denmark—Destruction of the German Empire— Napoleons visit to the Courts of Bavaria and Wurtemberg—His return to France—First mention of the divorce—Intelligence of Napoleon's marriage with Maria Louisa—Napoleon's quarrel with Louis—Journey of the Emperor and Empress into Holland—Refusal of the Hanse Towns to pay the French troops—Decree for burning English merchandise— M. de Vergennes—Plan for turning an inevitable evil to the best account—Fall on the exchange of St Petersburg |

| CHAPTER XXII. | 1809-1810. Bernadotte elected Prince Royal of Sweden—Count Wrede's overtures to Bernadotte—Bernadottes's three days' visit to Hamburg— Particulars respecting the battle of Wagram—Secret Order of the day—Last intercourse of the Prince Royal of Sweden with Napoleon— My advice to Bernadotte respecting the Continental system. |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | 1810 Bernadotte's departure from Hamburg—The Duke of Holstein-Augustenburg—Arrival of the Crown Prince in Sweden— Misunderstandings between him and Napoleon—Letter from Bernadotte to the Emperor—Plot for kidnapping the Prince Royal of Sweden— Invasion of Swedish Pomerania—Forced alliance of Sweden with England and Russia—Napoleon's overtures to Sweden—Bernadotte's letters of explanation to the Emperor—The Princess Royal of Sweden —My recall to Paris—Union of the Hanse Towns with France— Dissatisfaction of Russia—Extraordinary demand made upon me by Bonaparte—Fidelity of my old friends—Duroc and Rapp—Visit to Malmaison, and conversation with Josephine. |

| CHAPTER XXIV | 1811 Arrest of La Sahla—My visit to him—His confinement at Vincennes— Subsequent history of La Sahla—His second journey to France— Detonating powder—Plot hatched against me by the Prince of Eckmuhl —Friendly offices of the Duc de Rovigo—Bugbears of the police— Savary, Minister of Police. |

| CHAPTER XXV. | 1811 M. Czernischeff—Dissimulation of Napoleon—Napoleon and Alexander— Josephine's foresight respecting the affairs of Spain—My visits to Malmaison—Grief of Josephine—Tears and the toilet—Vast extent of the Empire—List of persons condemned to death and banishment in Piedmont—Observation of Alfieri respecting the Spaniards—Success in Spain—Check of Massena in Portugal—Money lavished by the English—Bertrand sent to Illyria, and Marmont to Portugal— Situation of the French army—Assembling of the Cortes—Europe sacrificed to the Continental system—Conversation with Murat in the Champs Elysees—New titles and old names—Napoleon's dislike of literary men—Odes, etc., on the marriage of Napoleon—Chateaubriand and Lemereier—Death of Chenier—Chateaubriand elected his successor —His discourse read by Napoleon—Bonaparte compared to Nero— Suppression of the 'Merceure'—M. de Chateaubriand ordered to leave Paris—MM. Lemercier and Esmenard presented to the Emperor—Birth of the King of Rome—France in 1811. |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | 1811 My return to Hamburg—Government Committee established there— Anecdote of the Comte de Chaban—Napoleon's misunderstanding with the Pope—Cardinal Fesch—Convention of a Council—Declaration required from the Bishops—Spain in 1811—Certainty of war with Russia—Lauriston supersedes Caulaincourt at St. Petersburg—The war in Spain neglected—Troops of all nations at the disposal of Bonaparte—Levy of the National Guard—Treaties with Prussia and Austria—Capitulation renewed with Switzerland—Intrigues with Czernischeff—Attacks of my enemies—Memorial to the Emperor—Ogier de la Saussaye and the mysterious box—Removal of the Pope to Fontainebleau—Anecdote of His Holiness and M. Denon—Departure of Napoleon and Maria Louisa for Dresden—Situation of affairs in Spain and Portugal—Rapp's account of the Emperor's journey to Dantzic— Mutual wish for war on the part of Napoleon and Alexander—Sweden and Turkey—Napoleon's vain attempt to detach Sweden from her alliance with Russia. |

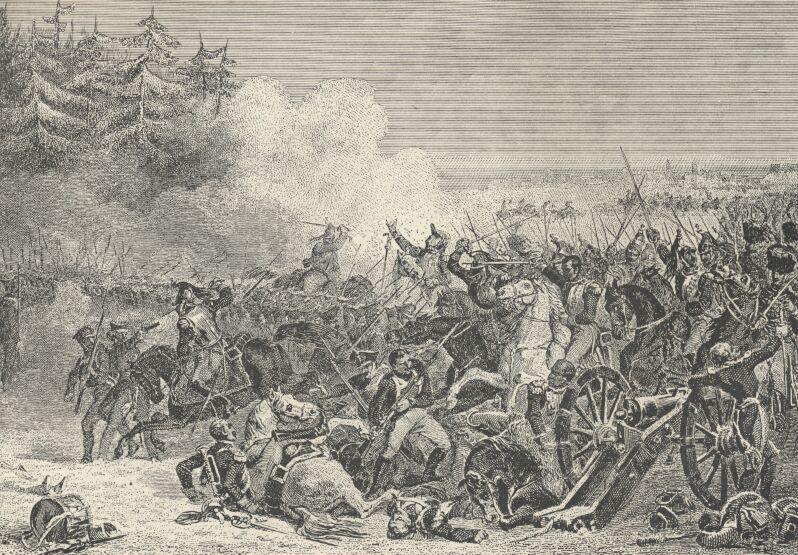

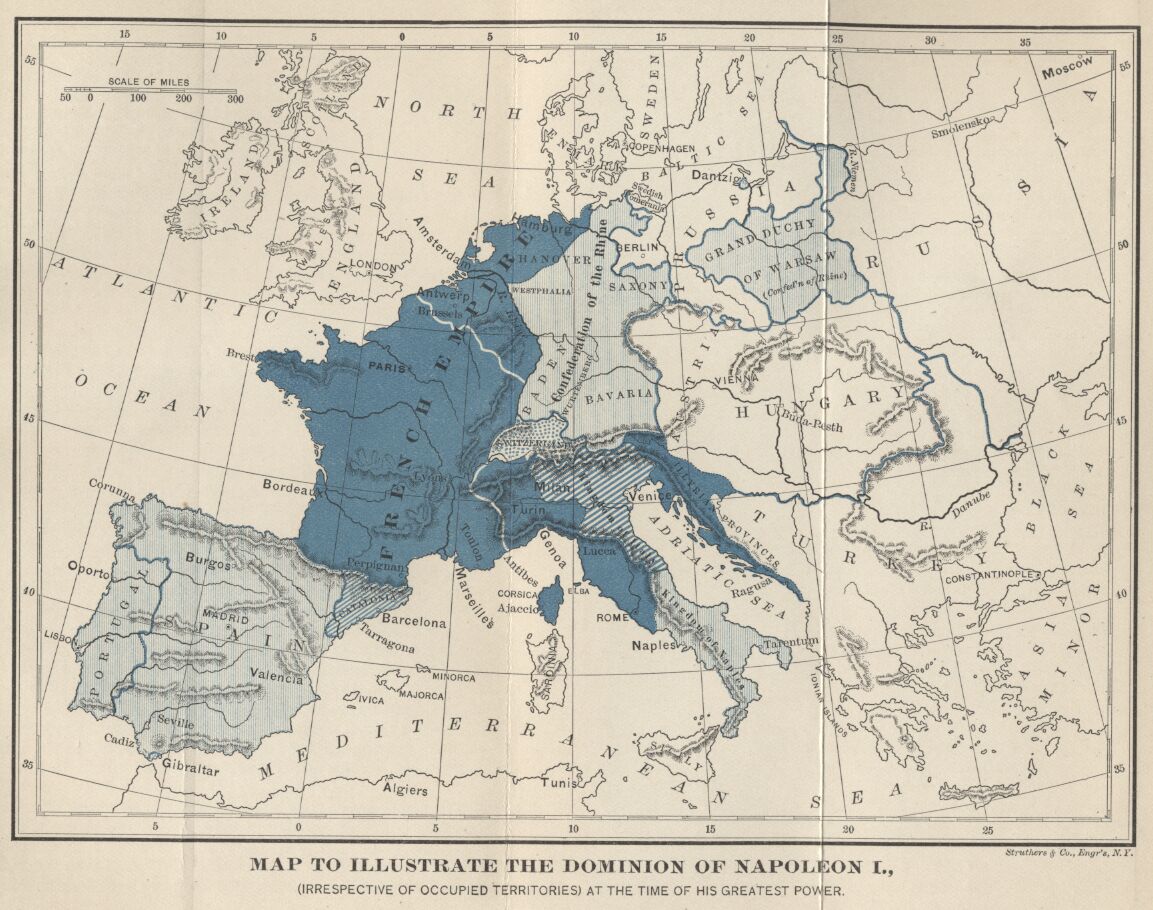

| CHAPTER XXVII. | 1812. Changeableness of Bonaparte's plans and opinions—Articles for the 'Moniteur' dictated by the First Consul—The Protocol of the Congress of Chatillon—Conversations with Davoust at Hamburg— Promise of the Viceroyalty of Poland—Hope and disappointment of the Poles—Influence of illusion on Bonaparte—The French in Moscow— Disasters of the retreat—Mallet's conspiracy—Intelligence of the affair communicated to Napoleon at Smolensko—Circumstances detailed by Rapp—Real motives of Napoleon's return to Paris—Murat, Ney, and Eugène—Power of the Italians to endure cold—Napoleon's exertions to repair his losses—Defection of General York—Convocation of a Privy Council—War resolved on—Wavering of the Pope—Useless negotiations with Vienna—Maria Louisa appointed Regent. |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | 1813. Riots in Hamburg and Lübeck—Attempted suicide of M. Konning— Evacuation of Hamburg—Dissatisfaction at the conduct of General St. Cyr—The Cabinets of Vienna and the Tuileries—First appearance of the Cossacks—Colonel Tettenborn invited to occupy Hamburg—Cordial reception of the Russians—Depredations—Levies of troops— Testimonials of gratitude to Tettenborn—Napoleon's new army—Death of General Morand—Remarks of Napoleon on Vandamme—Bonaparte and Gustavus Adolphus—Junction of the corps of Davoust and Vandamme— Reoccupation of Hamburg by the French—General Hogendorff appointed Governor of Hamburg—Exactions and vexatious contributions levied upon Hamburg and Lübeck—Hostages. |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | 1813. Napoleon's second visit to Dresden—Battle of Bantzen—The Congress at Prague—Napoleon ill- advised—Battle of Vittoria—General Moreau Rupture of the conferences at Prague—Defection of Jomini—Battles of Dresden and Leipsic—Account of the death of Duroc—An interrupted conversation resumed a year after—Particulars respecting Poniatowski—His extraordinary courage and death— His monument at Leipsic and tomb in the cathedral of Warsaw. |

| CHAPTER XXX. | 1813 Amount of the Allied forces against Napoleon—Their advance towards the Rhine—Levy of 280,000 men—Dreadful situation of the French at Mayence—Declaration of the Allies at Frankfort—Diplomatic correspondents—The Duc de Bassano succeeded by the Duke of Vicenza —The conditions of the Allies vaguely accepted—Caulaincourt sent to the headquarters of the Allies—Manifesto of the Allied powers to the French people.—Gift of 30,000,000 from the Emperor's privy purse—Wish to recall M. de Talleyrand—Singular advice relative to Wellington—The French army recalled from Spain—The throne resigned Joseph—Absurd accusation against M. Laine—Adjournment of the Legislative Body—Napoleon's Speech to the Legislative Body—Remarks of Napoleon reported by Cambacérès. |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | 1813. The flag of the army of Italy and the eagles of 1813—Entrance of the Allies into Switzerland—Summons to the Minister of Police— My refusal to accept a mission to Switzerland—Interviews with M. de Talleyrand and the Duc de Picence—Offer of a Dukedom and the Grand Cordon of the Legion of Honour—Definitive refusal—The Duc de Vicence's message to me in 1815—Commencement of the siege of Hamburg—A bridge two leagues long—Executions at Lübeck—Scarcity of provisions in Hamburg—Banishment of the inhabitants—Men bastinadoed and women whipped—Hospitality of the inhabitants of Altona. |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | 1813-1814. Prince Eugène and the affairs of Italy—The army of Italy on the frontiers of Austria—Eugène's regret at the defection of the Bavarians—Murat's dissimulation and perfidy—His treaty with Austria—Hostilities followed by a declaration of war—Murat abandoned by the French generals—Proclamation from Paris—Murat's success—Gigantic scheme of Napoleon—Napoleon advised to join the Jacobins—His refusal—Armament of the National Guard—The Emperor's farewell to the officers—The Congress of Chatillon—Refusal of an armistice—Napoleon's character displayed in his negotiations— Opening of the Congress—Discussions—Rupture of the Conferences. |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | 1814 Curious conversation between General Reynier and the Emperor Alexander—Napoleon repulses the Prussians—The Russians at Fontainebleau—Battle of Brienne—Sketch of the campaign of France— Supper after the battle of Champ Aubert—Intelligence of the arrival of the Duc d'Angouleme and the Comte d'Artois in France—The battle of the ravens and the eagle—Battle of Craonne—Departure of the Pope and the Spanish Princes—Capture of a convoy—Macdonald at the Emperor's headquarters—The inverted cipher. |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | 1814. The men of the Revolution and the men of the Empire—The Council of Regency—Departure of the Empress from Paris—Marmont and Mortier— Joseph's flight—Meeting at Marmont's hotel—Capitulation of Paris— Marmont's interview with the Emperor at Fontainebleau—Colonels Fabvier and Denys—The Royalist cavalcade—Meeting at the hotel of the Comte de Morfontaine—M. de Chateaubriand and his pamphlet— Deputation to the Emperor Alexander—Entrance of the Allied sovereigns into Paris—Alexander lodged in M. Talleyrand's hotel— Meetings held there—The Emperor Alexander's declaration— My appointment as Postmaster-General—Composition of the Provisional Government—Mistake respecting the conduct of the Emperor of Austria—Caulaincourt's mission from Napoleon—His interview with the Emperor Alexander—Alexander's address to the deputation of the Senate—M. de Caulaincourt ordered to quit the capital. |

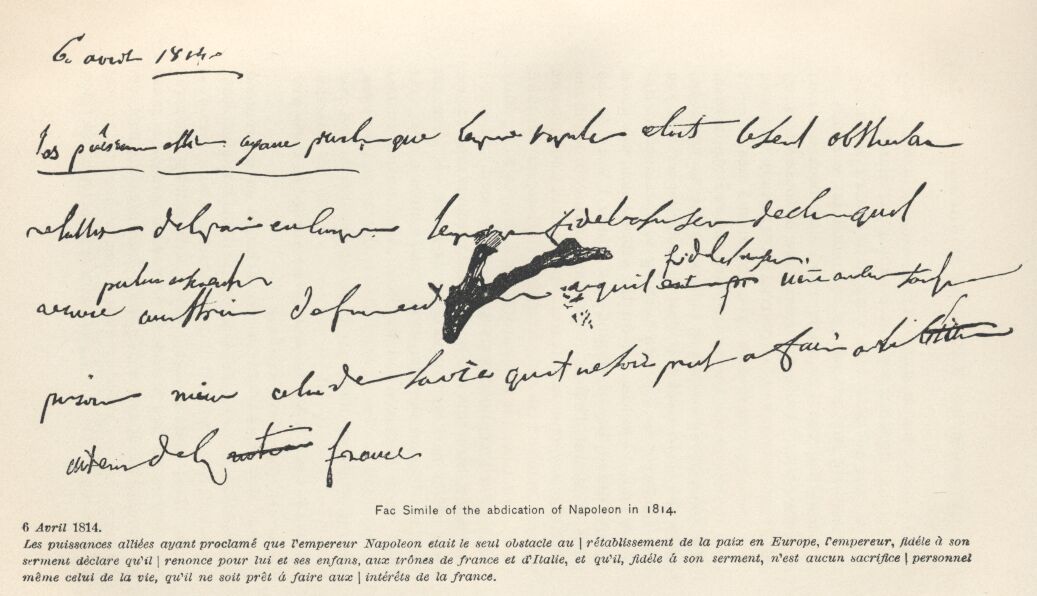

| CHAPTER XXXV. | 1814. Situation of Bonaparte during the events of the 30th and 31st of March—His arrival at Fontainebleau—Plan of attacking Paris— Arrival of troops at Fontainebleau—The Emperor's address to the Guard—Forfeiture pronounced by the Senate—Letters to Marmont— Correspondence between Marmont and Schwartzenberg—Macdonald informed of the occupation of Paris—Conversation between the Emperor and Macdonald at Fontainebleau—Beurnonville's letter— Abdication on condition of a Regency—Napoleon's wish to retract his act of abdication—Macdonald Ney, and Caulaincourt sent to Paris— Marmont released from his promise by Prince Schwartzenberg. |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | 1814. Unexpected receipts in the Post-office Department—Arrival of Napoleon's Commissioners at M. de Talleyrand's—Conference of the Marshals with Alexander—Alarming news from Essonne—Marmont's courage—The white cockade and the tri-coloured cockade— A successful stratagem—Three Governments in France—The Duc de Cadore sent by Maria Louisa to the Emperor of Austria—Maria Louisa's proclamation to the French people—Interview between the Emperor of Austria and the Duc de Cadore—The Emperor's protestation of friendship for Napoleon—M. Metternich and M. Stadion—Maria Louisa's departure for Orleans—Blücher's visit to me—Audience of the King of Prussia—His Majesty's reception of Berthier, Clarke, and myself—Bernadotte in Paris—Cross of the Polar Star presented to me by Bernadotte. |

| VOLUME IV. — 1814-1821 | |

| CHAPTER I. | 1814. Unalterable determination of the Allies with respect to Napoleon— Fontainebleau included in the limits to be occupied by the Allies— Alexander's departure from Paris—Napoleon informed of the necessity of his unconditional abdication—Macdonald and Ney again sent to Paris—Alleged attempt of Napoleon to poison himself—Farewell interview between Macdonald and Napoleon—The sabre of Murad Bey— Signature of the act of unconditional abdication—Tranquillity of Paris during the change of Government—Ukase of the Emperor of Russia relative to the Post-office—Religious ceremony on the Place Louis XV.—Arrival of the Comte d'Artois—His entrance into Paris— Arrival of the Emperor of Austria—Singular assemblage of sovereigns in France—Visit of the Emperor of Austria to Maria Louisa—Her interview with the Emperor Alexander—Her departure for Vienna. |

| CHAPTER II. | 1814. Italy and Eugène—Siege of Dantzic-Capitulation concluded but not ratified-Rapp made prisoner and sent to Kiew—Davoust's refusal to believe the intelligence from Paris—Projected assassination of one of the French Princes—Departure of Davoust and General Hogendorff from Hamburg—The affair of Manbreuil—Arrival of the Commissioners of the Allied powers at Fontainebleau—Preference shown by Napoleon to Colonel Campbell—Bonaparte's address to General Kohler—His farewell to his troops—First day of Napoleon's journey—The Imperial Guard succeeded by the Cossacks—Interview with Augereau— The first white cockades—Napoleon hanged in effigy at Orgon—His escape in the disguise of a courier—Scene in the inn of La Calade— Arrival at Aix—The Princess Pauline—Napoleon embarks for Elba—His life at Elba. |

| CHAPTER III. | 1814. Changes produced by time—Correspondence between the Provisional Government and Hartwell—Louis XVIII's reception in London— His arrival at Calais—Berthier's address to the King at Compiegne— My presentation to his Majesty at St. Ouen-Louis—XVIII's entry into Paris—Unexpected dismissal from my post—M. de Talleyrand's departure for the Congress of Vienna—Signs of a commotion— Impossibility of seeing M. de Blacas—The Abby Fleuriel—Unanswered letters—My letter to M. de Talleyrand at Vienna. |

| CHAPTER IV. | 1814-1815. Escape from Elba—His landing near Cannes—March on Paris. |

| CHAPTER V. | 1815. Message from the Tuileries—My interview with the King— My appointment to the office of Prefect of the Police—Council at the Tuileries—Order for arrests—Fouches escape—Davoust unmolested—Conversation with M. de Blacas—The intercepted letter, and time lost—Evident understanding between Murat and Napoleon— Plans laid at Elba—My departure from Paris—The post-master of Fins—My arrival at Lille—Louis XVIII. detained an hour at the gates—His majesty obliged to leave France—My departure for Hamburg—The Duc de Berri at Brussels. |

| CHAPTER VI. | 1815. Message to Madame de Bourrienne on the 20th of March—Napoleon's nocturnal entrance into Paris—General Becton sent to my family by Caulaincourt—Recollection of old persecutions—General Driesen— Solution of an enigma—Seals placed on my effects—Useless searches —Persecution of women—Madame de Stael and Madame de Recamier— Paris during the Hundred Days—The federates and patriotic songs— Declaration of the Plenipotentiaries at Vienna. |

| CHAPTER VII. | 1815.—[By the Editor of the 1836 edition]—Napoleon at Paris—Political manoeuvres—The meeting of the Champ-de-Mai—Napoleon, the Liberals, and the moderate Constitutionalists—His love of arbitrary power as strong as ever— Paris during the Cent Jours—Preparations for his last campaign— The Emperor leaves Paris to join the army—State of Brussels— Proclamation of Napoleon to the Belgians—Effective strength of the French and Allied armies—The Emperor's proclamation to the French army. |

| CHAPTER VIII. | 1815. —[Like the preceding, this chapter first appeared in the 1836 edition, and is not from the pen of M. de Bourrienne.]— THE BATTLES OF LIGNY AND QUATRE BRAS. |

| CHAPTER IX. | 1815 THE BATTLE OF WATERLOO. |

| CHAPTER X. | 1815 Interview with Lavallette—Proceedings in the French Chambers— Second abdication of Napoleon—He retires to Rochefort, negotiates with Captain Maitland, and finally embarks in the 'Bellerophon'. |

| CHAPTER XI. | 1815. My departure from Hamburg—The King at St. Denis—Fouché appointed Minister of the Police—Delay of the King's entrance into Paris— Effect of that delay—Fouché's nomination due to the Duke of Wellington—Impossibility of resuming my post—Fouché's language with respect to the Bourbons—His famous postscript—Character of Fouché—Discussion respecting the two cockades—Manifestations of public joy repressed by Fouché—Composition of the new Ministry— Kind attention of Blücher—The English at St. Cloud—Blücher in Napoleon's cabinet—My prisoner become my protector—Blücher and the innkeeper's dog—My daughter's marriage contract—Rigid etiquette— My appointment to the Presidentship of the Electoral College of the Yonne—My interview with Fouché—My audience of the King—His Majesty made acquainted with my conversation with Fouché—The Duke of Otranto's disgrace—Carnot deceived by Bonaparte—My election as deputy—My colleague, M. Raudot—My return to Paris—Regret caused by the sacrifice of Ney—Noble conduct of Macdonald—A drive with Rapp in the Bois de Boulogne—Rapp's interview with Bonaparte in 1815—The Duc de Berri and Rapp—My nomination to the office of Minister of State—My name inscribed by the hand of Louis XVIII.— Conclusion. |

| CHAPTER XII. | THE CENT JOURS. |

| CHAPTER XIII | 1815-1821.—[This chapter; by the editor of the 1836 edition, is based upon the 'Memorial', and O'Meara's and Antommarchi's works.]— Voyage to St. Helena—Personal traits of the Emperor—Arrival at James Town—Napoleon's temporary residence at The Briars—Removal to Longwood—The daily routine there-The Campaign of Italy—The arrival of Sir Hudson Lowe—Unpleasant relations between the Emperor and the new Governor—Visitors at St. Helena—Captain Basil Hall's interview with Napoleon—Anecdotes of the Emperor—Departure of Las Cases and O'Meara—Arrivals from Europe—Physical habits of the Emperor—Dr. Antommarchi—The Emperor's toilet—Creation of a new bishopric— The Emperor's energy with the spade—His increasing illness— Last days of Napoleon—His Death—Lying in state—Military funeral— Marchand's account of the Emperor's last moments—Napoleon's last bequests—The Watch of Rivoli. |

| I. | NAPOLEON I. (First Portrait) |

| II. | LETITIA RAMOLINO |

| III. | THE EMPRESS JOSEPHINE(First Portrait) |

| IV. | EUGENE BEAUHARNAIS |

| V. | GENERAL KLEBER |

| VI. | MARSHAL LANNES |

| VII. | TALLEYRAND |

| VIII. | GENERAL DUROC |

| IX. | MURAT, KING OF NAPLES |

| I. | THE EMPRESS JOSEPHINE (Second Portrait) |

| II. | GENERAL DESAIX |

| III. | GENERAL MOREAU |

| IV. | HORTENSE BEAUHARNAIS |

| V. | THE DUC D'ENGHEIN |

| VI. | GENERAL PICHEGRU |

In introducing the present edition of M. de Bourrienne's Memoirs to the public we are bound, as Editors, to say a few Words on the subject. Agreeing, however, with Horace Walpole that an editor should not dwell for any length of time on the merits of his author, we shall touch but lightly on this part of the matter. We are the more ready to abstain since the great success in England of the former editions of these Memoirs, and the high reputation they have acquired on the European Continent, and in every part of the civilised world where the fame of Bonaparte has ever reached, sufficiently establish the merits of M. de Bourrienne as a biographer. These merits seem to us to consist chiefly in an anxious desire to be impartial, to point out the defects as well as the merits of a most wonderful man; and in a peculiarly graphic power of relating facts and anecdotes. With this happy faculty Bourrienne would have made the life of almost any active individual interesting; but the subject of which the most favourable circumstances permitted him to treat was full of events and of the most extraordinary facts. The hero of his story was such a being as the world has produced only on the rarest occasions, and the complete counterpart to whom has, probably, never existed; for there are broad shades of difference between Napoleon and Alexander, Caesar, and Charlemagne; neither will modern history furnish more exact parallels, since Gustavus Adolphus, Frederick the Great, Cromwell, Washington, or Bolivar bear but a small resemblance to Bonaparte either in character, fortune, or extent of enterprise. For fourteen years, to say nothing of his projects in the East, the history of Bonaparte was the history of all Europe!

With the copious materials he possessed, M. de Bourrienne has produced a work which, for deep interest, excitement, and amusement, can scarcely be paralleled by any of the numerous and excellent memoirs for which the literature of France is so justly celebrated.

M. de Bourrienne shows us the hero of Marengo and Austerlitz in his night-gown and slippers—with a 'trait de plume' he, in a hundred instances, places the real man before us, with all his personal habits and peculiarities of manner, temper, and conversation.

The friendship between Bonaparte and Bourrienne began in boyhood, at the school of Brienne, and their unreserved intimacy continued during the most brilliant part of Napoleon's career. We have said enough, the motives for his writing this work and his competency for the task will be best explained in M. de Bourrienne's own words, which the reader will find in the Introductory Chapter.

M. de Bourrienne says little of Napoleon after his first abdication and retirement to Elba in 1814: we have endeavoured to fill up the chasm thus left by following his hero through the remaining seven years of his life, to the "last scenes of all" that ended his "strange, eventful history,"—to his deathbed and alien grave at St. Helena. A completeness will thus be given to the work which it did not before possess, and which we hope will, with the other additions and improvements already alluded to, tend to give it a place in every well-selected library, as one of the most satisfactory of all the lives of Napoleon.

LONDON, 1836.

The Memoirs of the time of Napoleon may be divided into two classes—those by marshals and officers, of which Suchet's is a good example, chiefly devoted to military movements, and those by persons employed in the administration and in the Court, giving us not only materials for history, but also valuable details of the personal and inner life of the great Emperor and of his immediate surroundings. Of this latter class the Memoirs of Bourrienne are among the most important.

Long the intimate and personal friend of Napoleon both at school and from the end of the Italian campaigns in 1797 till 1802—working in the same room with him, using the same purse, the confidant of most of his schemes, and, as his secretary, having the largest part of all the official and private correspondence of the time passed through his hands, Bourrienne occupied an invaluable position for storing and recording materials for history. The Memoirs of his successor, Meneval, are more those of an esteemed private secretary; yet, valuable and interesting as they are, they want the peculiarity of position which marks those of Bourrienne, who was a compound of secretary, minister, and friend. The accounts of such men as Miot de Melito, Raederer, etc., are most valuable, but these writers were not in that close contact with Napoleon enjoyed by Bourrienne. Bourrienne's position was simply unique, and we can only regret that he did not occupy it till the end of the Empire. Thus it is natural that his Memoirs should have been largely used by historians, and to properly understand the history of the time, they must be read by all students. They are indeed full of interest for every one. But they also require to be read with great caution. When we meet with praise of Napoleon, we may generally believe it, for, as Thiers (Consulat., ii. 279) says, Bourrienne need be little suspected on this side, for although he owed everything to Napoleon, he has not seemed to remember it. But very often in passages in which blame is thrown on Napoleon, Bourrienne speaks, partly with much of the natural bitterness of a former and discarded friend, and partly with the curious mixed feeling which even the brothers of Napoleon display in their Memoirs, pride in the wonderful abilities evinced by the man with whom he was allied, and jealousy at the way in which he was outshone by the man he had in youth regarded as inferior to himself. Sometimes also we may even suspect the praise. Thus when Bourrienne defends Napoleon for giving, as he alleges, poison to the sick at Jaffa, a doubt arises whether his object was to really defend what to most Englishmen of this day, with remembrances of the deeds and resolutions of the Indian Mutiny, will seem an act to be pardoned, if not approved; or whether he was more anxious to fix the committal of the act on Napoleon at a time when public opinion loudly blamed it. The same may be said of his defence of the massacre of the prisoners of Jaffa.

Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne was born in 1769, that is, in the same year as Napoleon Bonaparte, and he was the friend and companion of the future Emperor at the military school of Brienne-le-Chateau till 1784, when Napoleon, one of the sixty pupils maintained at the expense of the State, was passed on to the Military School of Paris. The friends again met in 1792 and in 1795, when Napoleon was hanging about Paris, and when Bourrienne looked on the vague dreams of his old schoolmate as only so much folly. In 1796, as soon as Napoleon had assured his position at the head of the army of Italy, anxious as ever to surround himself with known faces, he sent for Bourrienne to be his secretary. Bourrienne had been appointed in 1792 as secretary of the Legation at Stuttgart, and had, probably wisely, disobeyed the orders given him to return, thus escaping the dangers of the Revolution. He only came back to Paris in 1795, having thus become an emigre. He joined Napoleon in 1797, after the Austrians had been beaten out of Italy, and at once assumed the office of secretary which he held for so long. He had sufficient tact to forbear treating the haughty young General with any assumption of familiarity in public, and he was indefatigable enough to please even the never-resting Napoleon. Talent Bourrienne had in abundance; indeed he is careful to hint that at school if any one had been asked to predict greatness for any pupil, it was Bourrienne, not Napoleon, who would have been fixed on as the future star. He went with his General to Egypt, and returned with him to France. While Napoleon was making his formal entry into the Tuileries, Bourrienne was preparing the cabinet he was still to share with the Consul. In this cabinet—our cabinet, as he is careful to call it—he worked with the First Consul till 1802.