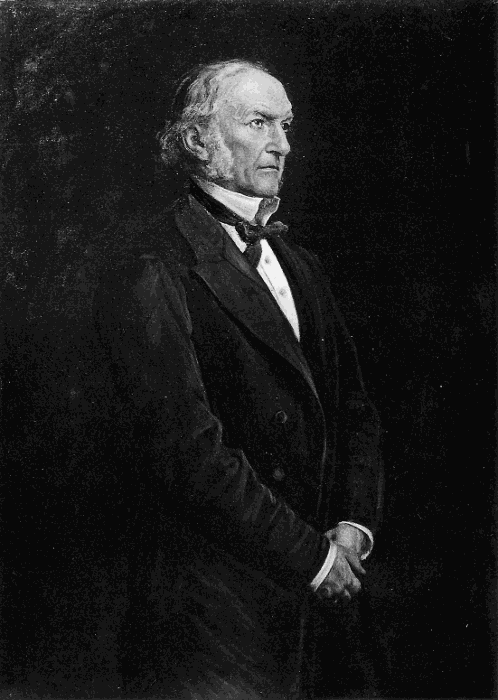

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) by John Morley

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) Author: John Morley Release Date: May 24, 2010, 2009 [Ebook #32510] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LIFE OF WILLIAM EWART GLADSTONE (VOL 2 OF 3)***

The Life Of

William Ewart Gladstone

By

John Morley

In Three Volumes—Vol. II.

(1859-1880)

Toronto

George N. Morang & Company, Limited

Copyright, 1903

By The Macmillan Company

Contents

- Book V. 1859-1868

- Chapter I. The Italian Revolution. (1859-1860)

- Chapter II. The Great Budget. (1860-1861)

- Chapter III. Battle For Economy. (1860-1862)

- Chapter IV. The Spirit Of Gladstonian Finance. (1859-1866)

- Chapter V. American Civil War. (1861-1863)

- Chapter VI. Death Of Friends—Days At Balmoral. (1861-1884)

- Chapter VII. Garibaldi—Denmark. (1864)

- Chapter VIII. Advance In Public Position And Otherwise. (1864)

- Chapter IX. Defeat At Oxford—Death Of Lord Palmerston—Parliamentary Leadership. (1865)

- Chapter X. Matters Ecclesiastical. (1864-1868)

- Chapter XI. Popular Estimates. (1868)

- Chapter XII. Letters. (1859-1868)

- Chapter XIII. Reform. (1866)

- Chapter XIV. The Struggle For Household Suffrage. (1867)

- Chapter XV. Opening Of The Irish Campaign. (1868)

- Chapter XVI. Prime Minister. (1868)

- Book VI. 1869-1874

- Chapter I. Religious Equality. (1869)

- Chapter II. First Chapter Of An Agrarian Revolution. (1870)

- Chapter III. Education—The Career And The Talents. (1870)

- Chapter IV. The Franco-German War. (1870)

- Chapter V. Neutrality And Annexation. (1870)

- Chapter VI. The Black Sea. (1870-1871)

- Chapter VII. “Day's Work Of A Giant”. (1870-1872)

- Chapter VIII. Autumn Of 1871. Decline Of Popularity. (1871-1872)

- Chapter IX. Washington And Geneva. (1870-1872)

- Chapter X. As Head Of A Cabinet. (1868-1874)

- Chapter XI. Catholic Country And Protestant Parliament. (1873)

- Chapter XII. The Crisis. (1873)

- Chapter XIII. Last Days Of The Ministry. (1873)

- Chapter XIV. The Dissolution. (1874)

- Book VII. 1874-1880

- Chapter I. Retirement From Leadership. (1874-1875)

- Chapter II. Vaticanism. (1874-1875)

- Chapter III. The Octagon.

- Chapter IV. Eastern Question Once More. (1876-1877)

- Chapter V. A Tumultuous Year. (1878)

- Chapter VI. Midlothian. (1879)

- Chapter VII. The Eve Of The Battle. (1879)

- Chapter VIII. The Fall Of Lord Beaconsfield. (1880)

- Chapter IX. The Second Ministry. (1880)

- Appendix

- Footnotes

Book V. 1859-1868

Chapter I. The Italian Revolution. (1859-1860)

This description extends in truth much beyond the session of a given year to the whole existence of the new cabinet, and through a highly important period in Mr. Gladstone's career. More than that, it directly links our biographic story to a series of events that created kingdoms, awoke nations, and re-made the map of Europe. The opening of this long and complex episode was the Italian revolution. Writing to Sir John Acton in 1864 Mr. Gladstone said to him of the budget of 1860, “When viewed as a whole, it is one of the few cases in which my fortunes as an individual have been closely associated with matters of a public and even an historic interest.” I will venture to recall in outline to the reader's memory the ampler background of this striking epoch in Mr. Gladstone's public life. The old principles [pg 002] of the European state-system, and the old principles that inspired the vast contentions of ages, lingered but they seemed to have grown decrepit. Divine right of kings, providential pre-eminence of dynasties, balance of power, sovereign independence of the papacy,—these and the other accredited catchwords of history were giving place to the vague, indefinable, shifting, but most potent and inspiring doctrine of Nationality. On no statesman of this time did that fiery doctrine with all its tributaries gain more commanding hold than on Mr. Gladstone. “Of the various and important incidents,” he writes in a memorandum, dated Braemar, July 16, 1892, “which associated me almost unawares with foreign affairs in Greece (1850), in the Neapolitan kingdom (1851), and in the Balkan peninsula and the Turkish empire (1853), I will only say that they all contributed to forward the action of those home causes more continuous in their operation, which, without in any way effacing my old sense of reverence for the past, determined for me my place in the present and my direction towards the future.”

I

At the opening of the seventh decade of the century—ten years of such moment for our western world—the relations of the European states with one another had fallen into chaos. The perilous distractions of 1859-62 were the prelude to conflicts that after strange and mighty events at Sadowa, Venice, Rome, Sedan, Versailles, came to their close in 1871. The first breach in the ramparts of European order set up by the kings after Waterloo, was the independence of Greece in 1829. Then followed the transformation of the power of the Turk over Roumanians and Serbs from despotism to suzerainty. In 1830 Paris overthrew monarchy by divine right; Belgium cut herself asunder from the supremacy of the Dutch; then Italians and Poles strove hard but in vain to shake off the yoke of Austria and of Russia. In 1848 revolts of race against alien dominion broke out afresh in Italy and Hungary. The rise of the French empire, bringing with it the principle or idiosyncrasy of its new ruler, carried [pg 003] this movement of race into its full ascendant. Treaties were confronted by the doctrine of Nationality. What called itself Order quaked before something that for lack of a better name was called the Revolution. Reason of State was eclipsed by the Rights of Peoples. Such was the spirit of the new time.

The end of the Crimean war and the peace of Paris brought a temporary and superficial repose. The French ruler, by strange irony at once the sabre of Revolution and the trumpet of Order, made a beginning in urging the constitution of a Roumanian nationality, by uniting the two Danubian principalities in a single quasi-independent state. This was obviously a further step towards that partition of Turkey which the Crimean war had been waged to prevent. Austria for reasons of her own objected, and England, still in her Turcophil humour, went with Austria against France for keeping the two provinces, although in fiscal and military union, politically divided. According to the fashion of that time—called a comedy by some, a homage to the democratic evangel by others—a popular vote was taken. Its result was ingeniously falsified by the sultan (whose ability to speak French was one of the odd reasons why Lord Palmerston was sanguine about Turkish civilisation); western diplomacy insisted that the question of union should be put afresh. Mr. Gladstone, not then in office, wrote to Lord Aberdeen (Sept. 10, 1857):—

In 1858 (May 4) he urged the Derby government to support the declared wish of the people of Wallachia and Moldavia, and to fulfil the pledges made at Paris in 1856. “Surely the best resistance to be offered to Russia,” he said, “is by the strength and freedom of those countries that will [pg 004] have to resist her. You want to place a living barrier between Russia and Turkey. There is no barrier like the breast of freemen.” The union of the Principalities would raise up antagonists to the ambitions of Russia more powerful than any that could be bought with money. The motion was supported by Lord John Russell and Lord Robert Cecil, but Disraeli and Palmerston joined in opposing it, and it was rejected by a large majority. Mr. Gladstone wrote in his diary: “May 4.—H. of C.—Made my motion on the Principalities. Lost by 292:114; and with it goes another broken promise to a people.” So soon did the illusions and deceptions of the Crimean war creep forth.

In no long time (1858) Roumania was created into a virtually independent state. Meanwhile, much against Napoleon's wish and policy, these proceedings chilled the alliance between France and England. Other powers grew more and more uneasy, turning restlessly from side to side, like sick men on their beds. The object of Russia ever since the peace had been, first to break down the intimacy between England and France, by flattering the ambition and enthusiasm of the French Emperor; next to wreak her vengeance on Austria for offences during the Crimean war, still pronounced unpardonable. Austria, in turn, was far too slow for a moving age; she entrenched herself behind forms with too little heed to substance; and neighbours mistook her dulness for dishonesty. For the diplomatic air was thick and dark with suspicion. The rivalry of France and Austria in Italy was the oldest of European stories, and for that matter the Lombardo-Venetian province was a possession of material value to Austria, for while only containing one-eighth of her population, it contributed one-fourth of her revenue.

The central figure upon the European stage throughout the time on which we are now about to enter was the ruler of France. The Crimean war appeared to have strengthened his dynasty at home, while faith in the depth of his political designs and in the grandeur of his military power had secured him predominance abroad. Europe hung upon his words; a sentence to an ambassador at a public audience on [pg 005] new year's day, a paragraph in a speech at the opening of his parliament of puppets, a pamphlet supposed to be inspired, was enough to shake Vienna, Turin, London, the Vatican, with emotions pitched in every key. Yet the mind of this imposing and mysterious potentate was the shadowy home of vagrant ideals and fugitive chimeras. It was said by one who knew him well, Scratch the emperor and you will find the political refugee. You will find, that is to say, the man of fluctuating hope without firm calculation of fact, the man of half-shaped end with no sure eye to means. The sphinx in our modern politics is usually something of a charlatan, and in time the spite of fortune brought this mock Napoleon into fatal conflict with the supple, positive, practical genius of Italy in the person of one of the hardiest representatives of this genius that Italy ever had; just as ten years later the same nemesis brought him into collision with the stern, rough genius of the north in the person of Count Bismarck. Meanwhile the sovereigns of central and northern Europe had interviews at Stuttgart, at Teplitz, at Warsaw. It was at Warsaw that the rulers of Austria and Prussia met the Czar at the end of 1860,—Poland quivering as she saw the three crowned pirates choose the capital city of their victim for a rendezvous. Russia declined to join what would have been a coalition against France, and the pope described the conference of Warsaw as three sovereigns assembling to hear one of them communicate to the other two the orders of the Emperor of the French. The French empire was at its zenith. Thiers said that the greatest compensation to a Frenchman for being nothing in his own country, was the sight of that country filling its right place in the world.

The reader will remember that at Turin on his way home from the Ionian Islands in the spring of 1859, Mr. Gladstone saw the statesman who was destined to make Italy. Sir James Hudson, our ambassador at the court of Piedmont, had sounded Cavour as to his disposition to receive the returning traveller. Cavour replied, “I hope you will do all you can to bring such a proceeding about. I set the highest value on the visit of a statesman so distinguished and such a friend of Italy as Mr. Gladstone.” In conveying this [pg 006] message to Mr. Gladstone (Feb. 7, 1859), Hudson adds, “I can only say I think your counsels may be very useful to this government, and that I look to your coming here as a means possibly of composing differences, which may, if not handled by some such calm unprejudiced statesman as yourself, lead to very serious disturbances in the European body politic.” Mr. Gladstone dined at Cavour's table at the foreign office, where, among other things, he had the satisfaction of hearing his host speak of Hudson as quel uomo italianissimo. Ministers, the president of the chamber, and other distinguished persons were present, and Cavour was well pleased to have the chance of freely opening his position and policy to “one of the sincerest and most important friends that Italy had.”2

Among Cavour's difficulties at this most critical moment was the attitude of England. The government of Lord Derby, true to the Austrian sympathies of his party, and the German sympathies of the court, accused Italy of endangering the peace of Europe. “No,” said Cavour, “it is the statesmen, the diplomatists, the writers of England, who are responsible for the troubled situation of Italy; for is it not they who have worked for years to kindle political passion in our peninsula, and is it not England that has encouraged Sardinia to oppose the propaganda of moral influences to the illegitimate predominance of Austria in Italy?” To Mr. Gladstone, who had seen the Austrian forces in Venetia and in Lombardy, he said, “You behold for yourself, that it is Austria who menaces us; here we are tranquil; the country is calm; we will do our duty; England is wrong in identifying peace with the continuance of Austrian domination.” Two or three days later the Piedmontese minister made one of those momentous visits to Paris that forced a will less steadfast than his own.

The French Emperor in his dealings with Cavour had entangled himself, in Mr. Gladstone's phrase, with “a stronger and better informed intellect than his own.” “Two men,” said Guizot, “at this moment divide the attention of Europe, the [pg 007] Emperor Napoleon and Count Cavour. The match has begun. I back Count Cavour.” The game was long and subtly played. It was difficult for the ruler who had risen to power by bloodstained usurpation and the perfidious ruin of a constitution, to keep in step with a statesman, the inspiring purpose of whose life was the deliverance of his country by the magic of freedom. Yet Napoleon was an organ of European revolution in a double sense. He proclaimed the doctrine of nationality, and paid decorous homage to the principle of appeal to the popular voice. In time England appeared upon the scene, and by his flexible management of the two western powers, England and France, Cavour executed the most striking political transformation in the history of contemporary Europe. It brought, however, as Mr. Gladstone speedily found, much trouble into the relations of the two western powers with one another.

The overthrow of the Derby government and the accession of the whigs exactly coincided in time with the struggle between Austria and the Franco-Sardinian allies on the bloody fields of Magenta and Solferino. A few days after Mr. Gladstone took office, the French and Austrian emperors and King Victor Emmanuel signed those preliminaries of Villafranca (July 11, 1859), which summarily ended an inconclusive war by the union of Lombardy to the Piedmontese kingdom, and the proposed erection of an Italian federation over which it was hoped that the pope might preside, and of which Venetia, still remaining Austrian, should be a member. The scheme was intrinsically futile, but it served its turn. The Emperor of the French was driven to peace by mixed motives. The carnage of Solferino appalled or unnerved him; he had revealed to his soldiers and to France that their ruler had none of the genius of a great commander; the clerical party at home fiercely assailed the prolongation of a war that must put the pope in peril; the case of Poland, the case of Hungary, might almost any day be kindled into general conflagration by the freshly lighted torch of Nationality; above all, Germany might stride forward to the Rhine to avenge the repulse of Austria on the Po and the Mincio.3

[pg 008]Whatever the motive, Villafranca was a rude check to Italian aspirations. Cavour in poignant rage peremptorily quitted office, rather than share responsibility for this abortive end of all the astute and deep-laid combinations for ten years past, that had brought the hated Austrian from the triumph of Novara down to the defeat of Solferino. Before many months he once more grasped the helm. In the interval the movement went forward as if all his political tact, his prudence, his suppleness, his patience, and his daring, had passed into the whole population of central Italy. For eight months after Villafranca, it seemed as if the deep and politic temper that built up the old Roman Commonwealth, were again alive in Bologna, Parma, Modena, Florence. When we think of the pitfalls that lay on every side, how easily France might have been irritated or estranged, what unseasonable questions might not unnaturally have been forced forward, what mischief the voice and spirit of the demagogue might have stirred up, there can surely be no more wonderful case in history of strong and sagacious leaders, Cavour, Farini, Ricasoli, the Piedmontese king, guiding a people through the ferments of revolt, with discipline, energy, legality, order, self-control, to the achievement of a constructive revolution. Without the sword of France the work could not have been begun; but it was the people and statesmen of northern and central Italy who in these eight months made the consummation possible. And England, too, had no inconsiderable share; for it was she who secured the principle of non-intervention by foreign powers in Italian affairs; it was she who strongly favoured the annexation of central Italy to the new kingdom in the north. Here it was that England directly and unconsciously opened the way to a certain proceeding that when it came to pass she passionately resented. In the first three weeks of March (1860) Victor Emmanuel legalised in due form the annexation of the four central states to Piedmont and Lombardy, and in the latter half of April he made his entry into Florence. Cavour attended him, and strange as it sounds, he now for the first time in his life beheld the famed city,—centre of undying beauty and so many glories in the [pg 009] history of his country and the genius of mankind. In one spot at least his musings might well have been profound—the tomb of Machiavelli, the champion of principles three centuries before, to guide that armed reformer, part fox part lion, who should one day come to raise up an Italy one and independent. The Florentine secretary's orb never quite sets, and it was now rising to a lurid ascendant in the politics of Europe for a long generation to come, lighting up the unblest gospel that whatever policy may demand justice will allow.4

On March 24 Cavour paid Napoleon a bitter price for his assent to annexation, by acquiescing in the cession to France of Savoy and Nice, provinces that were, one of them the cradle of the royal race, the other the birthplace of Garibaldi, the hero of the people. In this transaction the theory of the plébiscite, or direct popular vote upon a given question, for the first time found a place among the clauses of a diplomatic act. The plébiscite, though stigmatised as a hypocritical farce, and often no better than a formal homage paid by violence or intrigue to public right, was a derivative from the doctrines of nationality and the sovereignty of the people then ruling in Europe. The issue of the operation in Savoy and Nice was what had been anticipated. Italy bore the stroke with wise fortitude, but England when she saw the bargain closed for which she had herself prepared the way, took fierce umbrage at the aggrandisement of France, and heavy clouds floated into the European sky. As we have seen, the first act of the extraordinary drama closed at Villafranca. The curtain fell next at Florence upon the fusion of central with upper Italy. Piedmont, a secondary state, had now grown to be a kingdom with eleven or twelve millions of inhabitants. Greater things were yet to follow. Ten millions still remained in the south under the yoke of Bourbons and the Vatican. The third act, most romantic, most picturesque of all, an incomparable union of heroism with policy at double play with all the shifts of circumstance, opened a few weeks later.

[pg 010]The great unsolved problem was the pope. The French ambassador at the Vatican in those days chanced to have had diplomatic experience in Turkey. He wrote to his government in Paris that the pope and his cardinals reminded him of nothing so much as the sultan and his ulemas—the same vacillation, the same shifty helplessness, the same stubborn impenetrability. The Cross seemed in truth as grave a danger in one quarter of Europe as was the Crescent in another, and the pope was now to undergo the same course of territorial partition as had befallen the head of a rival faith. For ten years the priests had been maintained in their evilly abused authority by twenty thousand French bayonets—the bayonets of the empire that the cardinals with undisguised ingratitude distrusted and hated.5 The Emperor was eager to withdraw his force, if only he were sure that no catastrophe would result to outrage the catholic world and bring down his own throne.

Unluckily for this design, Garibaldi interposed. One night in May (1860), soon after the annexation to Piedmont of the four central states, the hero whom an admirer described as “a summary of the lives of Plutarch,” sailed forth from Genoa for the deliverance of the Sicilian insurgents. In the eyes of Garibaldi and his Thousand, Sicily and Naples marked the path that led to Rome. The share of Cavour as accomplice in the adventure is still obscure. Whether he even really desired the acquisition of the Neapolitan kingdom, or would have preferred, as indeed he attempted, a federation between a northern kingdom and a southern, is not established. How far he had made certain of the abstention of Louis Napoleon, how far he had realised the weakness of Austria, we do not authentically know. He was at least alive to all the risks to which Garibaldi's enterprise must instantly expose him in every quarter of the horizon—from Austria, deeming her hold upon Venetia at stake; from the French Emperor, with hostile clericals in France to face; from the whole army of catholics all over the world; and [pg 011] not least from triumphant Mazzinians, his personal foes, in whose inspirations he had no faith, whose success might easily roll him and his policy into mire and ruin. Now as always with consummate suppleness he confronted the necessities of a situation that he had not sought, and assuredly had neither invented nor hurried. The politician, he used to tell his friends, must above all things have the tact of the Possible. Well did Manzoni say of him, “Cavour has all the prudence and all the imprudence of the true statesman.” Stained and turbid are the whirlpools of revolution. Yet the case of Italy was overwhelming. Sir James Hudson wrote to Mr. Gladstone from Turin (April 3, 1859)—“Piedmont cannot separate the question of national independence from the accidental existence of constitutional liberty (in Piedmont) if she would. Misgovernment in central Italy, heavy taxation and dearth in Lombardy, misgovernment in Modena, vacillation in Tuscany, cruelty in Naples, constitute the famous grido di dolore. The congress of Paris wedded Piedmont to the redress of grievances.”

In August (1860) Garibaldi crossed from Sicily to the mainland and speedily made his triumphant entry into Naples. The young king Francis withdrew before him at the head of a small force of faithful adherents to Capua, afterwards to Gaeta. At the Volturno the Garibaldians, meeting a vigorous resistance, drove back a force of the royal troops enormously superior in numbers. On the height of this agitated tide, and just in time to forestall a fatal movement of Garibaldi upon Rome, the Sardinian army had entered the territories of the pope (September 11).

II

In the series of transactions that I have sketched, the sympathies of Mr. Gladstone never wavered. From the appearance of his Neapolitan letters in 1851, he lost no opportunity of calling attention to Italian affairs. In 1854 he brought before Lord Clarendon the miserable condition of Poerio, Settembrini, and the rest. He took great personal trouble in helping to raise and invest a fund for the Settembrini [pg 012] family, and elaborate accounts in his own handwriting remain. In 1855 he wrote to Lord John Russell, then starting for Vienna, as to a rumour of the adhesion of Naples to the alliance of the western powers: “In any case I can conceive it possible that the Vienna conferences may touch upon Italian questions; and I sincerely rely upon your humanity as well as your love of freedom, indeed the latter is but little in question, to plead for the prisoners in the kingdom of the two Sicilies detained for political offences, real or pretended. I do not ask you to leave any greater duty undone, but to bear in mind the singular claims on your commiseration of these most unhappy persons, if occasion offers.”

As we have already seen, it was long before he advanced to the view of the thoroughgoing school. Like nearly all his countrymen, he was at first a reformer, not a revolutionary. To the Marquis Dragonetti, Mr. Gladstone wrote from Broadstairs in 1854:—

So far removed at this date was Mr. Gladstone from the glorified democracy of the Mazzinian propaganda. He told Cobden that when he returned from Corfu in the spring of 1859, he found in England not only a government with strong Austrian leanings, but to his great disappointment not even the House of Commons so alive as he could have wished upon the Italian question. “It was in my opinion the authority and zeal of Lord Palmerston and Lord John Russell in this question, that kindled the country.”

While Europe was anxiously watching the prospects of war between France and Austria, Mr. Gladstone spoke in debate (April 18, 1859) upon the situation, to express his firm conviction that no plan of peace could be durable which failed to effect some mitigation of the sore evils afflicting the Italian peninsula. The course of events after the peace speedily ripened both his opinions and the sentiment of the country, and he was as angry as his neighbours at the unexpected preliminaries of Villafranca. “I little thought,” he wrote to Poerio (July 15, 1859), “to have lived to see the day when the conclusion of a peace should in my own mind cause disgust rather than impart relief. But that day has come. I appreciate all the difficulties of the position both of the King of Sardinia and of Count Cavour. It is hardly possible for me to pass a judgment upon his resignation as a political step: but I think few will doubt that the moral character of the act is high. The duties of England in respect to the Italian question are limited by her powers, and these are greatly [pg 014] confined. But her sentiments cannot change, because they are founded upon a regard to the deepest among those principles which regulate the intercourse of men and their formation into political societies.” By the end of the year, he softened his judgment of the proceedings of the French Emperor.

The heavy load of his other concerns did not absolve him in his conscience from duty to the Italian cause:—

In a cabinet memorandum (Jan. 3, 1860), he declared himself bound in candour to admit that the Emperor had shown, “though partial and inconsistent, indications of a genuine feeling for the Italians—and far beyond this he has committed himself very considerably to the Italian cause in the face of the world. When in reply to all that, we fling in his face the truce of Villafranca, he may reply—and the answer is not without force—that he stood single-handed in a cause when any moment Europe might have stood combined against him. We gave him verbal sympathy and encouragement, or at least criticism; no one else gave him anything at all. No doubt he showed then that he had undertaken a work to which his powers were unequal; but I do not think that, when fairly judged, he can be said to have given proof by that measure of insincerity or indifference.” This was no more than justice, it is even less; and both Italians and Englishmen have perhaps been too ready to forget that the freedom of Italy would have remained an empty hope if Napoleon iii. had not unsheathed his sword.

After discussing details, Mr. Gladstone laid down in his memorandum a general maxim for the times, that “the [pg 015] alliance with France is the true basis of peace in Europe, for England and France never will unite in any European purpose which is radically unjust.” He put the same view in a letter to Lacaita a few months later (Sept. 16): “A close alliance between England and France cannot be used for mischief, and cannot provoke any dangerous counter combination; but a close alliance between England and other powers would provoke a dangerous counter combination immediately, besides that it could not in itself be trusted. My own leaning, therefore, is not indeed to place reliance on the French Emperor, but to interpret him candidly, and in Italian matters especially to recollect the great difficulties in which he is placed, (1) because, whether by his own fault or not, he cannot reckon upon strong support from England when he takes a right course. (2) Because he has his own ultramontane party in France to deal with, whom, especially if not well supported abroad, he cannot afford to defy.”

As everybody soon saw, it was the relation of Louis Napoleon to the French ultramontanes that constituted the tremendous hazard of the Piedmontese invasion of the territories of the pope. This critical proceeding committed Cavour to a startling change, and henceforth he was constrained to advance to Italian unity. A storm of extreme violence broke upon him. Gortchakoff said that if geography had permitted, the Czar would betake himself to arms in defence of the Bourbon king. Prussia talked of reviving the holy alliance in defence of the law of nations against the overweening ambition of Piedmont. The French ambassador was recalled from Turin. Still no active intervention followed.

One great power alone stood firm, and Lord John Russell wrote one of the most famous despatches in the history of our diplomacy (October 27, 1860). The governments of the pope and the king of the Two Sicilies, he said, provided so ill for the welfare of their people, that their subjects looked to their overthrow as a necessary preliminary to any improvement. Her Majesty's government were bound to admit that the Italians themselves are the best judges of their own [pg 016] interests. Vattel, that eminent jurist, had well said that when a people for good reasons take up arms against an oppressor, it is but an act of justice and generosity to assist brave men in the defence of their liberties. Did the people of Naples and the Roman States take up arms against their government for good reasons? Upon this grave matter, her Majesty's government held that the people in question are themselves the best judges of their own affairs. Her Majesty's government did not feel justified in declaring that the people of Southern Italy had not good reasons for throwing off their allegiance to their former governments. Her Majesty's government, therefore, could not pretend to blame the King of Sardinia for assisting them. So downright was the language of Lord John. We cannot wonder that such words as these spread in Italy like flame, that people copied the translation from each other, weeping over it for joy and gratitude in their homes, and that it was hailed as worth more than a force of a hundred thousand men.6

The sensation elsewhere was no less profound, though very different. The three potentates at Warsaw viewed the despatch with an emotion that was diplomatically called regret, but more resembled horror. The Prince Regent of Prussia, afterwards the Emperor William, told Prince Albert that it was a tough morsel, a disruption of the law of nations and of the holy ties that bind peoples to their sovereigns.7 Many in England were equally shocked. Even Sir James Graham, for instance, said that he would never have believed that such a document could have passed through a British cabinet or received the approval of a British sovereign; India, Ireland, Canada would await the application of the fatal doctrine that it contained; it was a great public wrong, a grave error; and even Garibaldi and Mazzini would come out of the Italian affair with cleaner hands. Yet to-day we may ask ourselves, was it not a little idle to talk of the holy ties that bind nations to their sovereigns, in respect of a system under which in Naples thousands of the most respectable of the subjects of the king were in prison or in exile; in the papal states ordinary justice was administered by rough-handed [pg 017] German soldiers, and young offenders shot by court-martial at the drumhead; and in the Lombardo-Venetian provinces press offences were judged by martial law, with chains, shooting, and flogging for punishment.8 Whatever may be thought of Lord John and his doctrine, only those who hold to the converse doctrine, that subjects may never rise against a king, nor ever under any circumstances seek succour from foreign power, will deny that the cruelties of Naples and the iniquities connected with the temporal authority of the clergy in the states of the church, constituted an irrefragable case for revolt.

Within a few weeks after the troops of Victor Emmanuel had crossed the frontier (Sept. 1860), the papal forces had been routed, and a popular vote in the Neapolitan kingdom supported annexation to Piedmont. The papal states, with the exception of the patrimony of St. Peter in the immediate neighbourhood of Rome itself, fell into the hands of the king. Victor Emmanuel and Garibaldi rode into Naples side by side (Nov. 7). The Bourbon flag after a long stand was at last lowered at the stronghold of Gaeta (Feb. 14, 1861); the young Bourbon king became an exile for the rest of his life; and on February 18 the first parliament of united Italy assembled at Turin—Venice and Rome for a short season still outside. A few months before, Mr. Gladstone had written a long letter to d'Azeglio. It was an earnest exposition of the economic and political ideals that seemed to shine in the firmament above a nation now emerging from the tomb. The letter was to be shown to Cavour. “Tell that good friend of ours,” he replied, “that our trade laws are the most liberal of the continent; that for ten years we have been practising the maxims that he exhorts us to adopt; tell him that he preaches to the converted.”9 Then one of those disasters happened that seem to shake the planetary nations out of their pre-appointed orbits. Cavour died.10

Chapter II. The Great Budget. (1860-1861)

I

As we survey the panorama of a great man's life, conspicuous peaks of time and act stand out to fix the eye, and in our statesman's long career the budget of 1860 with its spurs of appendant circumstance, is one of these commanding points. In the letter to Acton already quoted (p. 1), Mr. Gladstone says:—

The financial arrangements of 1859 were avowedly provisional and temporary, and need not detain us. The only feature was a rise in the income tax from fivepence to ninepence—its highest figure so far in a time of peace. “My budget,” he wrote to Mrs. Gladstone (July 16), “is just through the cabinet, very kindly and well received, no one making objection but Lewis, who preached low doctrine. It confirms me in the belief I have long had, that he was fitter for most other offices than for that I now hold.” “July 21 or rather 22, one A.M.—Just come back from a long night and stiff contention at the House of Commons.... It has been rather nice and close fighting. Disraeli made a popular motion to trip me up, but had to withdraw it, at any rate for the time. This I can say, it was not so that I used him. I am afraid that the truce between us is over, and that we shall have to pitch in as before.”

The only important speech was one on Italy (August 8),13 of which Disraeli said that though they were always charmed by the speaker's eloquence, this was a burst of even unusual brilliance, and it gave pleasure in all quarters. “Spoke for an oretta [short hour],” says the orator, “on Italian affairs; my best offhand speech.” “The fish dinner,” Mr. Gladstone writes, “went off very well, and I think my proposing Lord Palmerston's health (without speech) was decidedly approved. I have had a warm message from Lord Lansdowne about my speech; and Lord P. told me that on Tuesday night as he went upstairs on getting home he heard Lady P. spouting as she read by candle-light; it turned out to be the same effusion.”

Another incident briefly related to Mrs. Gladstone brings us on to more serious ground: “Hawarden, Sept. 12.—Cobden [pg 020] came early. Nothing could be better than the luncheon, but I am afraid the dinner will be rather strong with local clergy. I have had a walk and long talk with Cobden who, I think, pleases and is pleased.” This was the garden walk of which we have just heard, where Cobden, the ardent hopeful sower, scattered the good seed into rich ground. The idea of a commercial treaty with France was in the air. Bright had opened it, Chevalier had followed it up, Persigny agreed, Cobden made an opportunity, Gladstone seized it. Cobden's first suggestion had been that as he was about to spend a part of the winter in Paris, he might perhaps be of use to Mr. Gladstone in the way of inquiry. Conversation expanded this into something more definite and more energetic. Why should he not, with the informal sanction of the British government, put himself into communication with the Emperor and his ministers, and work out with them the scheme of a treaty that should at once open the way to a great fiscal reform in both countries, and in both countries produce a solid and sterling pacification of feeling? Cobden saw Palmerston and tried to see Lord John Russell, and though he hardly received encouragement, at least he was not forbidden to proceed upon his volunteered mission.14 “Gladstone,” wrote Cobden to Mr. Bright, “is really almost the only cabinet minister of five years' standing who is not afraid to let his heart guide his head a little at times.” The Emperor had played with the idea of a more open trade for five or six years, and Cobden, with his union of economic, moral, and social elements, and his incomparable gifts of argumentative persuasion, was the very man to strike Napoleon's impressionable mind. Although, having alienated the clericals by his Italian policy, the ruler of France might well have hesitated before proceeding to alienate the protectionists also, he became a convert and did not shrink.

At the end of 1859 the question of the treaty was brought into the cabinet, and there met with no general opposition, though some objection was taken by Lewis and Wood, based on the ground that they ought not to commit themselves by treaty engagements to a sacrifice of revenue, until they had before them the income and the charges of the year. Writing to his wife about some invitation to a country house, Mr. Gladstone says (Jan. 11, 1860):—

I cannot go without a clear sacrifice of public duty. For the measure is of immense importance and of no less nicety, and here [pg 022] it all depends on me. Lord John backs me most cordially and well, but it is no small thing to get a cabinet to give up one and a half or two millions of revenue at a time when all the public passion is for enormous expenditure, and in a case beset with great difficulties. In fact, a majority of the cabinet is indifferent or averse, but they have behaved very well. I almost always agree with Lewis on other matters, but in trade and finance I do not find his opinions satisfactory. Till it is through, this vital question will need my closest and most anxious attention. [Two days later he writes:] The cabinet has been again on the French treaty. There are four or five zealous, perhaps as many who would rather be without it. It has required pressure, but we have got sufficient power now, if the French will do what is reasonable. Lord John has been excellent, Palmerston rather neutral. It is really a great European operation. [A fortnight later (Jan. 28):] A word to say I have opened the fundamental parts of my budget in the cabinet, and that I could not have hoped a better reception. Nothing decided, for I did not ask it, and indeed the case was not complete, but there was no general [resistance], no decided objection; the tone of questioning was favourable, Granville and Argyll delighted, Newcastle, I think, ditto. Thank God.

To Cobden, Jan. 28.—Criticism is busy; but the only thing really formidable is the unavowed but strong conflict with that passionate expectation of war, which no more bears disappointment than if it were hope or love. Feb. 6.—Cobbett once compared an insignificant public man in an important situation to the linch-pin in the carriage, and my position recalls his very apt figure to my mind.

Of course in his zeal for the treaty and its connection with tariff reform, Mr. Gladstone believed that the operation would open a great volume of trade and largely enrich the country. But in one sense this was the least of it:—

II

Out of the commercial treaty grew the whole of the great financial scheme of 1860. By his first budget Mr. Gladstone had marked out this year for a notable epoch in finance. Happily it found him at the exchequer. The expiry of certain annuities payable to the public creditor removed a charge of some two millions, and Mr. Gladstone was vehemently resolved that this amount should not “pass into the great gulf of expenditure there to be swallowed up.” If the year, in such circumstances, is to pass, he said to Cobden, “without anything done for trade and the masses, it will be a great discredit and a great calamity.” The alterations of duty required for the French treaty were made possible by the lapse of the annuities, and laid the foundation of a plan that averted the discredit and calamity of doing nothing for trade, and nothing for the masses of the population. France engaged to reduce duties and remove prohibitions on a long list of articles of British production and export, iron the most important,—“the daily bread of all industries,” as Cobden called it. England engaged immediately to abolish all duties upon all manufactured articles at her ports, and to reduce the duties on wine and brandy. The English reductions and abolitions extended beyond France to the commodities of all countries alike. Mr. Gladstone called 1860 the last of the cardinal and organic years of emancipatory fiscal legislation; it ended [pg 024] a series of which the four earlier terms had been reached in 1842, in 1845, in 1846, and 1853. With the French treaty, he used to say, the movement in favour of free trade reached its zenith.

The financial fabric that rose from the treaty was one of the boldest of all his achievements, and the reader who seeks to take the measure of Mr. Gladstone as financier, in comparison with any of his contemporaries in the western world, will find in this fabric ample material.16 Various circumstances had led to an immense increase in national expenditure. The structure of warships was revolutionised by the use of iron in place of wood. It was a remarkable era in artillery, and guns were urgently demanded of new type. In the far East a quarrel had broken out with the Chinese. The threats of French officers after the plot of Orsini had bred a sense of insecurity in our own borders. Thus more money than ever was required; more than ever economy was both unpopular and difficult. The annual estimates stood at seventy millions; when Mr. Gladstone framed his famous budget seven years before, that charge stood at fifty-two millions. If the sole object of a chancellor of the exchequer be to balance his account, Mr. Gladstone might have contented himself with keeping the income-tax and duties on tea and sugar as they were, meeting the remissions needed by the French treaty out of the sum released by the expiry of the long annuities. Or he might have reduced tea and sugar to a peace rate, and raised the income-tax from ninepence to a shilling. Instead of taking this easy course, Mr. Gladstone after having relinquished upwards of a million for the sake of the French treaty, now further relinquished nearly a million more for the sake of releasing 371 articles from duties of customs, and a third million in order to abolish the vexatious excise duty upon the manufacture of paper. Nearly one million of all this loss he recouped by the imposition of certain small charges and minor [pg 025] taxes, and by one or two ingenious expedients of collection and account, and the other two millions he made good out of the lapsed annuities. Tea and sugar he left as they were, and the income-tax he raised from ninepence to tenpence. Severe economists, not quite unjustly, called these small charges a blot on his escutcheon. Time soon wiped it off, for in fact they were a failure.

The removal of the excise duty upon paper proved to be the chief stumbling-block, and ultimately it raised more excitement than any other portion of the scheme. The fiscal project became by and by associated with a constitutional struggle between Lords and Commons. In the Commons the majority in favour of abolishing the duty sank from fifty-three to nine; troubles with China caused a demand for new expenditure; the yield from the paper duty was wanted; and the Lords finding in all this a plausible starting-point for a stroke of party business, or for the assertion of the principle that to reject a repealing money bill was not the same thing as to meddle with a bill putting on a tax, threw it out. Then when the Lords had rejected the bill, many who had been entirely cool about taking off the 'taxes upon knowledge'—for this unfavourable name was given to the paper duty by its foes—rose to exasperation at the thought of the peers meddling with votes of money. All this we shall see as we proceed.

This was the broad outline of an operation that completed the great process of reducing articles liable to customs duties from 1052, as they stood in 1842 when Peel opened the attack upon them; from 466 as Mr. Gladstone found them in 1853; and from 419 as he found them now, down to 48, at which he now left them.17 Simplification had little further to go. “Why did you not wait,” he was asked, “till the surplus came, which notwithstanding all drawbacks you got in [pg 026] 1863, and then operate in a quiet way, without disturbing anybody?”18 His answer was that the surplus would not have come at all, because it was created by his legislation. “The principle adopted,” he said, “was this. We are now (1860) on a high table-land of expenditure. This being so, it is not as if we were merely meeting an occasional and momentary charge. We must consider how best to keep ourselves going during a period of high charge. In order to do that, we will aggravate a momentary deficiency that we may thereby make a great and permanent addition to productive power.” This was his ceaseless refrain—the steadfast pursuit of the durable enlargement of productive power as the commanding aim of high finance.

III

At the beginning of the year the public expectation was fixed upon Lord John Russell as the protagonist in the approaching battle of parliamentary reform, and the eager partizans at the Carlton Club were confident that on reform they would pull down the ministry. The partizans of another sort assure us that “the whole character of the session was changed by Mr. Gladstone's invincible resolution to come forward in spite of his friends, and in defiance of his foes, for his own aristeia or innings.” The explanation is not good-natured, and we know that it is not true; but what is true is that when February opened, the interest of the country had become centred at its highest pitch in the budget and the commercial treaty. As the day for lifting the veil was close at hand, Mr. Gladstone fell ill, and here again political benevolence surmised that his disorder was diplomatic. An entry or two from Phillimore's journal will bring him before us as he was:—

Mr. Gladstone's own entries are these:—

Of the speech in which the budget was presented everybody agreed that it was one of the most extraordinary triumphs ever witnessed in the House of Commons. The [pg 028] casual delay of a week had raised expectation still higher; hints dropped by friends in the secret had added to the general excitement; and as was truly said by contemporaries, suspense that would have been fatal to mediocrity actually served Mr. Gladstone. Even the censorious critics of the leading journal found in the largeness and variety of the scheme its greatest recommendation, as suggesting an accord between the occasion, the man, and the measure, so marvellous that it would be a waste of all three not to accept them. Among other hearers was Lord Brougham, who for the first time since he had quitted the scene of his triumphs a generation before, came to the House of Commons, and for four hours listened intently to the orator who had now acquired the supremacy that was once his own. “The speech,” said Bulwer, “will remain among the monuments of English eloquence as long as the language lasts.” Napoleon begged Lord Cowley to convey his thanks to Mr. Gladstone for the copy of his budget speech he had sent him, which he said he would preserve “as a precious souvenir of a man who has my thorough esteem, and whose eloquence is of a lofty character commensurate with the grandeur of his views.” Prince Albert wrote to Stockmar (March 17), “Gladstone is now the real leader of the House, and works with an energy and vigour almost incredible.”20

Almost every section of the trading and political community looked with favour upon the budget as a whole, though it was true that each section touched by it found fault with its own part. Mr. Gladstone said that they were without exception free traders, but not free traders without exception. The magnitude and comprehensiveness of the enterprise seized the imagination of the country. At the same time it multiplied sullen or uneasy interests. The scheme was no sooner launched, than the chancellor of the exchequer was overwhelmed by deputations. Within a couple of days he was besieged by delegates from the paper makers; distillers came down upon him; merchants interested in the bonding system, wholesale stationers, linen manufacturers, maltsters, licensed victuallers, all in turn [pg 029] thronged his ante-room. He was now, says Greville (Feb. 15), “the great man of the day!” The reduction of duties on currants created lively excitement in Greece, and Mr. Gladstone was told that if he were to appear there he could divide honours with Bacchus and Triptolemus, the latest benefactors of that neighbourhood.

Political onlookers with whom the wish was not alien to their thought, soon perceived that in spite of admiration for splendid eloquence and incomparable dexterity, it would not be all sunshine and plain sailing. At a very early moment the great editor of the Times went about saying that Gladstone would find it hard work to get his budget through; if Peel with a majority of ninety needed it all to carry his budget, what would happen to a government that could but command a majority of nine?21 Both the commercial treaty and the finance speedily proved to have many enemies. Before the end of March Phillimore met a parliamentary friend who like everybody else talked of Gladstone, and confirmed the apprehension that the whigs obeyed and trembled and were frightened to death. “We don't know where he is leading us,” said Hayter, who had been whipper-in. On the last day of the month Phillimore enters: “March 30.—Gladstone has taken his name off the Carlton, which I regret. It is a marked and significant act of entire separation from the whole party and will strengthen Disraeli's hands. The whigs hate Gladstone. The moderate conservatives and the radicals incline to him. The old tories hate him.” For reasons not easy to trace, a general atmosphere of doubt and unpopularity seemed suddenly to surround his name.

The fortunes of the budget have been succinctly described by its author:—

When Lord John had asked the cabinet to stop the budget in order to fix a day for his second reading, Mr. Gladstone enters in an autobiographic memorandum of his latest years23:—

On May 5 the diary reports: “Cabinet. Lord Palmerston spoke 3/4 hour against Paper Duties bill! I had to reply. Cabinet against him, except a few, Wood and Cardwell in particular. Three wild schemes of foreign alliance are afloat! Our old men (2) are unhappily our youngest.” Palmerston not only spoke against the bill, as he had a right in cabinet to do, but actually wrote to the Queen that he was bound in duty to say that if the Lords threw out the bill—the bill of his own cabinet—“they would perform a good public service.”24

Phillimore's notes show that the intense strain was telling on his hero's physical condition, though it only worked his resolution to a more undaunted pitch:—

IV

The rejection of the bill affecting the paper duty by the Lords was followed by proceedings set out by Mr. Gladstone in one of his political memoranda, dated May 26, 1860:—

Though I seldom have time to note the hairbreadth 'scapes of which so many occur in these strange times and with our strangely constructed cabinet, yet I must put down a few words with respect to the great question now depending between the Lords and the English nation. On Sunday, when it was well known that the Paper Duties bill would be rejected, I received from Lord John Russell a letter which enclosed one to him from Lord Palmerston. Lord Palmerston's came in sum to this: that the vote of the Lords would not be a party vote, that as to the thing done it was right, that we could not help ourselves, that we should simply acquiesce, and no minister ought to resign. Lord John in his reply to this, stated that he took a much more serious view of the question and gave reasons. Then he went on to say that though he did not agree in the grounds stated by Lord Palmerston, he would endeavour to arrive at the same conclusion. His letter accordingly ended with practical acquiescence. And he stated to me his concurrence in Lord Palmerston's closing proposition.

Thereupon I wrote an immediate reply. We met in cabinet to consider the case. Lord Palmerston started on the line he had marked out. I think he proposed to use some meaningless words in the House of Commons as to the value we set on our privileges, and our determination to defend them if attacked, by way of garniture to the act of their abandonment. Upon this I stated my opinions, coming to the point that this proceeding of the House of Lords amounted to the establishment of a revising power over the House of Commons in its most vital function long declared exclusively its own, and to a divided responsibility in fixing the revenue and charge of the country for the year; besides aggravating circumstances upon which it was needless to dwell. In this proceeding nothing would induce me to acquiesce, though I earnestly desired that the mildest means of correction should be adopted. This was strongly backed in principle by Lord John; who thought that as public affairs would not admit of our at once confining ourselves to this subject, we should take [pg 033] it up the first thing next session, and send up a new bill. Practical, as well as other, objections were taken to this mode of proceeding, and opposition was continued on the merits; Lord Palmerston keen and persevering. He was supported by the Chancellor, Wood, Granville (in substance), Lewis, and Cardwell, who thought nothing could be done, but were ready to join in resigning if thought fit. Lord John, Gibson, and I were for decided action. Argyll leaned the same way. Newcastle was for inquiry to end in a declaratory resolution. Villiers thought some step necessary. Grey argued mildly, inclined I think to inaction. Herbert advised resignation, opposed any other course. Somerset was silent, which I conceive meant inaction. At last Palmerston gave in, and adopted with but middling grace the proposition to set out with inquiries, and with the intention to make as little of the matter as he could.

His language in giving notice, on Tuesday, of the committee went near the verge of saying, We mean nothing. An unsatisfactory impression was left on the House. Not a syllable was said in recognition of the gravity of the occasion. Lord John had unfortunately gone away to the foreign office. I thought I should do mischief at that stage by appearing to catch at a part in the transaction. Yesterday all was changed by the dignified declaration of Lord John. I suggested to him that he should get up, and Lord Palmerston, who had intended to keep the matter in his own hands, gave way. But Lord Palmerston was uneasy and said, “You won't pitch it into the Lords,” and other things of the same kind. On the whole, I hope that in this grave matter at least we have turned the corner.

As we know, even the fighting party in the cabinet was forced to content itself for the moment with three protesting resolutions. Lord Palmerston and his chancellor of the exchequer both spoke in parliament. “The tone of the two remonstrances,” says Mr. Gladstone euphemistically, “could not be in exact accord; but by careful steering on my part, and I presume on his, all occasion of scandal was avoided.” Not altogether, perhaps. Phillimore says:—

The struggle still went on:—

July 20.—H. of C. Lost my Savings Bank Monies bill; my first defeat in a measure of finance in the H. of C. This ought to be very good for me; and I earnestly wish to make it so.

Aug. 6.—H. of C. Spoke 1-½ hour on the Paper duty; a favourable House. Voted in 266-233. A most kind and indeed notable reception afterwards.

Aug. 7.—This was a day of congratulations from many kind M.P.'s.

The occasion of the notable reception was the moving of his resolutions reducing the customs duty on imported paper to the level of the excise duty. This proceeding was made necessary by the treaty, and was taken to be, as Mr. Gladstone intended that it should be, a clear indication of further determination to abolish customs duty and excise duty alike. The first resolution was carried by 33, and when he rose to move the second the cheering from the liberal benches kept him standing for four or five minutes—cheering intended to be heard the whole length of the corridor that led to another place.25

[pg 035]

The great result, as Greville says in a sentence that always amused the chief person concerned, is “to give some life to half-dead, broken-down, and tempest-tossed Gladstone.” In this rather tame fashion the battle ended for the session, but the blaze in the bosom of the chancellor of the exchequer was inextinguishable, as the Lords in good time found out. Their rejection of the Paper Duties bill must have had no inconsiderable share in propelling him along the paths of liberalism. The same proceeding helped to make him more than ever the centre of popular hopes. He had taken the unpopular side in resisting the inquiry into the miscarriages of the Crimea, in pressing peace with Russia, in opposing the panic on papal aggression, on the bill for divorce, and on the bill against church rates; and he represented with fidelity the constituency that was least of all in England in accord with the prepossessions of democracy. Yet this made no difference when the time came to seek a leader. “There is not,” Mr. Bright said, in the course of this quarrel with the Lords, “a man who labours and sweats for his daily bread, there is not a woman living in a cottage who strives to make her home happy for husband and children, to whom the words of the chancellor of the exchequer have not brought hope, and to whom his measures, which have been defended with an eloquence few can equal and with a logic none can contest, have not administered consolation.”

At the end of the session Phillimore reports:—

V

In a contemporary memorandum (May 30, 1860) on the opinions of the cabinet at this date Mr. Gladstone sets out the principal trains of business with which he and his colleagues were called upon to deal. It is a lively picture of the vast and diverse interests of a minister disposed to take his cabinet duties seriously. It is, too, a curious chart of the currents and cross-currents of the time. Here are the seven heads as he sets them down:—

“In the many passages of argument and opinion,” Mr. Gladstone adds, “the only person from whom I have never to my recollection differed on a serious matter during this anxious twelvemonth is Milner Gibson.” The reader will find elsewhere the enumeration of the various parts in this complex dramatic piece.26 Some of the most Italian members of the cabinet were also the most combative in foreign policy, the most martial in respect [pg 037] of defence, the most stationary in finance. In the matter of reform, some who were liberal as to the franchise were conservative as to redistribution. In matters ecclesiastical, those who like Mr. Gladstone were most liberal elsewhere, were (with sympathy from Argyll) “most conservative and church-like.”

Before he had been a year and a half in office, Mr. Gladstone wrote to Graham (Nov. 27, '60): “We live in anti-reforming times. All improvements have to be urged in apologetic, almost in supplicatory tones. I sometimes reflect how much less liberal as to domestic policy in any true sense of the word, is this government than was Sir Robert Peel's; and how much the tone of ultra-toryism prevails among a large portion of the liberal party.” “I speak a literal truth,” he wrote to Cobden, “when I say that in these days it is more difficult to save a shilling than to spend a million.” “The men,” he said, “who ought to have been breasting and stemming the tide have become captains general of the alarmists,” and he deplored Cobden's refusal [pg 038] of office when the Palmerston government was formed. All this only provoked him to more relentless energy. Well might Prince Albert call it incredible.

VI

After the “gigantic innovation” perpetrated by the Lords, Mr. Gladstone read to the cabinet (June 30, 1860) an elaborate memorandum on the paper duty and the taxing powers of the two Houses. He dealt fully alike with the fiscal and the constitutional aspects of a situation from which he was “certain that nothing could extricate them with credit, except the united, determined, and even authoritative action of the government.” He wound up with a broad declaration that, to any who knew his tenacity of purpose when once roused, made it certain that he would never acquiesce in the pretensions of the other House. The fiscal consideration, he concluded, “is nothing compared with the vital importance of maintaining the exclusive rights of the House of Commons in matter of supply. There is hardly any conceivable interference of the Lords hereafter, except sending down a tax imposed by themselves, which would not be covered by this precedent. It may be said they are wise and will not do it. Assuming that they will be wise, yet I for one am not willing that the House of Commons should hold on sufferance in the nineteenth century what it won in the seventeenth and confirmed and enlarged in the eighteenth.”

The intervening months did not relax this valiant and patriotic resolution. He wrote down a short version of the story in the last year of his life:—

Of the “internal fighting” we have a glimpse in the diary:—

The abiding feature of constitutional interest in the budget of 1861 was this inclusion of the various financial proposals in a single bill, so that the Lords must either accept the whole of them, or try the impossible performance of rejecting the whole of them. This was the affirmation in practical shape of the resolution of the House of Commons in the previous year, that it possessed in its own hands the power to remit and impose taxes, and that the right to frame bills of supply in its own measure, manner, time, and matter, is a right to be kept inviolable. Until now the practice had been to make the different taxes the subject of as many different bills, thus placing it in the power of the Lords to reject a given tax bill without throwing the financial machinery wholly out of gear. By including all the taxes in a single finance bill the power of the Lords to override the other House was effectually arrested.

In language of that time, he had carried every stitch of free-trade canvas in the teeth of a tempest that might have made the boldest financial pilot shorten sail. Many even of his friends were sorry that he did not reduce the war duty on tea and sugar, instead of releasing paper from its duty of excise. Neither friends nor foes daunted him. He possessed his soul in patience until the hour struck, and then came forth in full panoply. Enthusiastic journalists with the gift [pg 041] of a poetic pen told their millions of readers how, after weeks of malign prophecy, that the great trickster in Downing Street would be proved to have beggared the exchequer, that years of gloom and insolvency awaited us, suddenly, the moment the magician chose to draw aside the veil, the darkness rolled away; he had fluttered out of sight the whole race of sombre Volscians; and where the gazers dreaded to see a gulf they beheld a golden monument of glorious finance; like the traveller in the Arabian fable who was pursued in the Valley of Shadows by unearthly imprecations, he never glanced to right or left until he could disperse the shadows by a single stroke. “He is,” says another onlooker, “in his ministerial capacity, probably the best abused and the best hated man in the House; nevertheless the House is honestly proud of him, and even the country party feels a glow of pride in exhibiting to the diplomatic gallery such a transcendent mouthpiece of a nation of shopkeepers. The audacious shrewdness of Lancashire married to the polished grace of Oxford is a felicitous union of the strength and culture of liberal and conservative England; and no party in the House, whatever may be its likings or antipathies, can sit under the spell of Mr. Gladstone's rounded and shining eloquence without a conviction that the man who can talk ‘shop’ like a tenth Muse is, after all, a true representative man of the market of the world.”

In describing the result of the repeal of the paper duty a little after this,28 he used glowing words. “Never was there a measure so conservative as that which called into vivid, energetic, permanent, and successful action the cheap press of this country.” It was also a common radical opinion of that hour that if the most numerous classes acquired the franchise as well as cheap newspapers, the reign of peace would thenceforth be unbroken. In a people of bold and martial temper such as are the people of our island, this proved to be a miscalculation. Meanwhile there is little doubt that Mr. Gladstone's share in thus fostering the growth of the cheap press was one of the secrets of his rapid rise in popularity.

Chapter III. Battle For Economy. (1860-1862)

The session of 1860, with its complement in the principal part of 1861, was, I think, the most trying part of my whole political life.—Gladstone (1897).

In reading history, we are almost tempted to believe that the chief end of government in promoting internal quiet has been to accumulate greater resources for foreign hostilities.—Channing.

I

All this time the battle for thrifty husbandry went on, and the bark of the watch-dog at the exchequer sounded a hoarse refrain. “We need not maunder in ante-chambers,” as Mr. Disraeli put it, “to discover differences in the cabinet, when we have a patriotic prime minister appealing to the spirit of the country; and when at the same time we find his chancellor of the exchequer, whose duty it is to supply the ways and means by which those exertions are to be supported, proposing votes with innuendo, and recommending expenditure in a whispered invective.”

Severer than any battle in parliament is a long struggle inside a cabinet. Opponents contend at closer quarters, the weapons are shorter, it is easier to make mischief. Mr. Gladstone was the least quarrelsome of the human race; he was no wrestler intent only on being a winner in Olympic games; nor was he one of those who need an adversary to bring out all their strength. But in a cause that he had at heart he was untiring, unfaltering, and indomitable. Parallel with his contention about budget and treaty in 1860 was persistent contention for economy. The financial crisis went on with the fortifications crisis. The battle was incessant. He had not been many months in office before [pg 043] those deep differences came prominently forward in temperament, tradition, views of national policy, that continued to make themselves felt between himself and Lord Palmerston so long as the government endured. Perhaps I should put it more widely, and say between himself and that vast body of excited opinion in the country, of which Lord Palmerston was the cheerful mouthpiece. The struggle soon began.

Sidney Herbert, then at the war office, after circulating a memorandum, wrote privately to Mr. Gladstone (Nov. 23, 1859), that he was convinced that a great calamity was impending in the shape of a war provoked by France. Officers who had visited that country told him that all thinking men in France were against war with England, all noisy men for it, the army for it, and above all, the government for it. Inspired pamphlets were scattered broadcast. Everything was determined except time and occasion. The general expectation was for next summer. French tradesmen at St. Malo were sending in their bills to the English, thinking war coming. “We have to do with a godless people who look on war as a game open to all without responsibility or sin; and there is a man at the head of them who combines the qualities of a gambler and a fatalist.”

Mr. Gladstone replied in two letters, one of them (Nov. 27) of the stamp usual from a chancellor of the exchequer criticising a swollen estimate, with controversial doubts, pungent interrogatories, caustic asides, hints for saving here and paring there. On the following day he fired what he called his second barrel, in the shape of a letter, which states with admirable force and fulness the sceptic's case against the scare. This time it was no ordinary exchequer wrestle. He combats the inference of an English from an Italian war, by the historic reminder that a struggle between France and Austria for supremacy or influence in Italy had been going on for four whole centuries, so that its renewal was nothing strange. If France, now unable to secure our co-operation, still thought the Italian danger grave enough to warrant single-handed intervention, how does that support the inference that she must certainly be ready to invade England next? He ridicules the conclusion that the invasion [pg 044] was at our doors, from such contested allegations as that the Châlons farmers refused the loan of horses from the government, because they would soon be wanted back again for the approaching war with England. What extraordinary farmers to refuse the loan of horses for their ploughing and seed time, because they might be reclaimed for purposes of war before winter! Then why could we not see a single copy of the incendiary and anti-English pamphlets, said to be disseminated broadcast among the troops? What was the value of all this contested and unsifted statement? Why, if he were bent on a rupture, did the Emperor not stir at the moment of the great Mutiny, when every available man we had was sent to India, and when he had what might have passed for a plausible excuse in the Orsini conspiracy, and in the deliberate and pointed refusal of parliament to deal with it? With emphasis, he insists that we have no adequate idea of the predisposing power which an immense series of measures of preparation for war on our own part, have in actually begetting war. They familiarise ideas which when familiar lose their horror, and they light an inward flame of excitement of which, when it is habitually fed, we lose the consciousness.

This application of cool and reasoned common sense to actual probabilities seldom avails against imaginations excited by random possibilities; and he made little way. Lord Palmerston advanced into the field, in high anxiety that the cabinet should promptly adopt Herbert's proposal.29 They soon came to a smart encounter, and Mr. Gladstone writes to the prime minister (Feb. 7, 1860): “There are, I fear, the most serious differences among us with respect to a loan for fortifications.... My mind is made up, and to propose any loan for fortifications would be, on my part, with the views I entertain, a betrayal of my public duty.” A vigorous correspondence between Mr. Gladstone and Herbert upon military charges followed, and the tension seemed likely to snap the cord.

If I may judge from the minutes of the members of the cabinet on the papers circulated, most of them stood [pg 045] with their chief, and not one of them, not even Milner Gibson nor Villiers, was ready to proceed onward from a sort of general leaning towards Mr. Gladstone's view to the further stage of making a strong stand-up fight for it. The controversy between him and his colleagues still raged at red heat over the whole ground of military estimates, the handling of the militia, and the construction of fortifications. He wrote memorandum upon memorandum with untiring energy, pressing the cabinet with the enormous rate in the increase of charge; with the slight grounds on which increase of charge was now ordinarily proposed and entertained; and, most of all, with the absence of all attempt to compensate for new and necessary expenditure by retrenchment in quarters where the scale of outlay had either always been, or had become unnecessary. He was too sound a master of the conditions of public business to pretend to take away from the ministers at the head of the great departments of expenditure their duty of devising plans of reduction, but he boldly urged the reconsideration of such large general items of charge as the military expenditure in the colonies, then standing at an annual burden of over two millions on the taxpayers of this country. He was keen from the lessons of experience, to expose the ever indestructible fallacy that mighty armaments make for peace.

Still the cabinet was not moved, and in Palmerston he found a will and purpose as tenacious as his own. “The interview with Lord Palmerston came off to-day,” he writes to the Duke of Argyll (June 6, 1860). “Nothing could be more kind and frank than his manner. The matter was first to warn me of the evils and hazards attending, for me, the operation of resigning. Secondly, to express his own strong sense of the obligation to persevere. Both of these I told him I could fully understand. He said he had had two great objects always before him in life—one the suppression of the slave trade, the other to put England in a state of defence. In short, it appears that he now sees, as he considers, the opportunity of attaining a long cherished object; and it is not unnatural that he should repel any [pg 046] proposal which should defraud him of a glory, in and by absolving him from a duty.... I am now sure that Lord Palmerston entertained this purpose when he formed the government; but had I been in the slightest degree aware of it, I should certainly, but very reluctantly, have abstained from joining it, and helped, as I could, from another bench its Italian purposes. Still, I am far indeed from regretting to have joined it, which is quite another matter.”

Now labouring hard in Paris month after month at the tariff, Cobden plied Mr. Gladstone with exhortations to challenge the alarmists on the facts; to compare the outlay by France for a dozen years past on docks, fortifications, arsenals, with the corresponding outlay by England; to show that our steam navy, building and afloat, to say nothing of our vast mercantile marine, was at least double the strength of France; and above all, to make his colleagues consider whether the French Emperor had not, as a matter of self-interest, made the friendship of England, from the first, the hinge of his whole policy. Cobden, as always, knew thoroughly and in detail what he was talking about, for he had sat for three successive sessions on a select committee upon army, navy, and ordnance expenditure. In another letter he turned personally to Mr. Gladstone himself: “Unconsciously,” he says, “you have administered to the support of a system which has no better foundation than a gigantic delusion” (June 11, 1860). “You say unconsciously,” Mr. Gladstone replies (June 13), “I am afraid that in one respect this is too favourable a description. I have consciously, as a member of parliament and as a member of the government, concurred in measures that provide for an expenditure beyond what were it in my power I would fix.... But I suppose that the duty of choosing the lesser evil binds me; the difficulty is to determine what the lesser evil is.”