A STUDY OF

ENGLISH INFLUENCES IN BROWNING

BY

HELEN ARCHIBALD CLARKE

Author of "Browning's Italy"

NEW YORK

THE BAKER & TAYLOR COMPANY

MCMVIII

Copyright, 1908, by

The Baker & Taylor Company

Published, October, 1908

The Plimpton Press Norwood Mass. U.S.A.

To

MY COLLEAGUE IN PLEASANT LITERARY PATHS

and

MANY YEARS FRIEND

CHARLOTTE PORTER

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | English Poets, Friends, and Enthusiasms | 1 |

| II. | Shakespeare's Portrait | 42 |

| III. | A Crucial Period in English History | 79 |

| IV. | Social Aspects of English Life | 211 |

| V. | Religious Thought in the Nineteenth Century | 322 |

| VI. | Art Criticism Inspired by the English Musician, Avison | 420 |

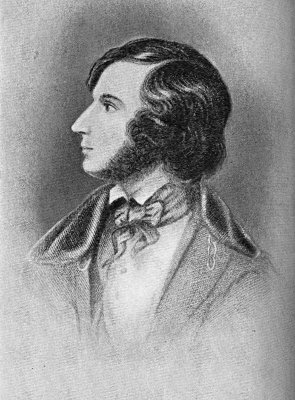

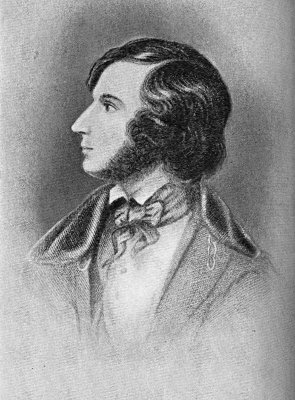

| Browning at 23 | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| Percy Bysshe Shelley | 4 |

| John Keats | 10 |

| William Wordsworth | 16 |

| Rydal Mount, the Home of Wordsworth | 22 |

| An English Lane | 33 |

| First Folio Portrait of Shakespeare | 60 |

| Charles I in Scene of Impeachment | 80 |

| Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford | 88 |

| Charles I | 114 |

| Whitehall | 120 |

| Westminster Hall | 157 |

| The Tower, London | 170 |

| The Tower, Traitors' Gate | 183 |

| An English Manor House | 222 |

| An English Park | 240 |

| John Bunyan | 274 |

| An English Inn | 288 |

| Cardinal Wiseman | 336 |

| Sacred Heart | 342 |

| The Nativity | 351 |

| The Transfiguration | 366 |

| Handel | 426 |

| Avison's March | 446 |

ENGLISH POETS, FRIENDS AND ENTHUSIASMS

To any one casually trying to recall what England has given Robert Browning by way of direct poetical inspiration, it is more than likely that the little poem about Shelley, "Memorabilia" would at once occur:

It puts into a mood and a symbol the almost worshipful admiration felt by Browning for the poet in his youth, which he had, many years before this little lyric was written, recorded in a finely appreciative passage in "Pauline."

Browning was only fourteen when Shelley first came into his literary life. The story has often been told of how the young Robert, passing a bookstall one day spied in a box of second-hand volumes, a shabby little edition of Shelley advertised "Mr. Shelley's Atheistical Poems: very scarce." It seems almost incredible to us now that the name was an absolutely new one to him, and that only by questioning the bookseller did he learn that Shelley had written a number of volumes of poetry and that he was now dead. This accident was sufficient to inspire the incipient poet's curiosity, and he never rested until he was the owner of Shelley's works. They were hard to get hold of in those early days but the persistent searching of his mother finally unearthed them at Olliers' in Vere Street, London. She brought him also three volumes of Keats, who became a treasure second only to Shelley.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

"Sun-treader, life and light be thine forever."

The question of Shelley's influence on Browning's art has been one often discussed. There are many traces of Shelleyan music and idea in his early poems "Pauline," "Paracelsus," and "Sordello," but no marked nor lasting impression was made upon Browning's development as a poet by Shelley. Upon5 Browning's personal development Shelley exerted a short-lived though somewhat intense influence. We see the young enthusiast professing the atheism of his idol as the liberal views of Shelley were then interpreted, and even becoming a vegetarian. As time went on the discipleship vanished, and in its place came the recognition on Browning's part of a poetic spirit akin yet different from his own. The last trace of the disciple appears in "Sordello" when the poet addresses Shelley among the audience of dead great ones he has mustered to listen to the story of Sordello:

Shelley appears in the work of Browning once more in the prose essay on Shelley which was written to a volume of spurious letters of that poet published in 1851. In this is summed up in a masterful paragraph6 reflecting Browning's unusual penetration into the secret paths of the poetic mind, the characteristics of a poet of Shelley's order. The paragraph is as follows:

"We turn with stronger needs to the genius of an opposite tendency—the subjective poet of modern classification. He, gifted like the objective poet, with the fuller perception of nature and man, is impelled to embody the thing he perceives, not so much with reference to the many below as to the One above him, the supreme Intelligence which apprehends all things in their absolute truth,—an ultimate view ever aspired to, if but partially attained, by the poet's own soul. Not what man sees, but what God sees,—the Ideas of Plato, seeds of creation lying burningly on the Divine Hand,—it is toward these that he struggles. Not with the combination of humanity in action, but with the primal elements of humanity, he has to do; and he digs where he stands,—preferring to seek them in his own soul as the nearest reflex of that absolute Mind, according to the intuitions of which he desires to perceive and speak. Such a poet does not deal habitually with the picturesque groupings and tempestuous tossings of the forest-trees, but with their roots and fibers naked to the chalk and stone. He7 does not paint pictures and hang them on the walls, but rather carries them on the retina of his own eyes: we must look deep into his human eyes, to see those pictures on them. He is rather a seer, accordingly, than a fashioner, and what he produces will be less a work than an effluence. That effluence cannot be easily considered in abstraction from his personality,—being indeed the very radiance and aroma of his personality, projected from it but not separated. Therefore, in our approach to the poetry, we necessarily approach the personality of the poet; in apprehending it, we apprehend him, and certainly we cannot love it without loving him. Both for love's and for understanding's sake we desire to know him, and, as readers of his poetry, must be readers of his biography too."

Finally, the little "Memorabilia" lyric gives a mood of cherished memory of the Sun-Treader, who beaconed him upon the heights in his youth, and has now become a molted eagle-feather held close to his heart.

Keats' lesser but assured place in the poet's affections comes out in the pugnacious lyric, "Popularity," one of the old-time bits of ammunition shot from the guns of those who found Browning "obscure." The poem is an "apology" for any unappreciated poet with8 the true stuff in him, but the allusion to Keats shows him to have been the fuse that fired this mild explosion against the dullards who pass by unknowing and uncaring of a genius, though he pluck with one hand thoughts from the stars, and with the other fight off want.

John Keats

|

"Who fished the murex up? |

11 Wordsworth, it appears, was, so to speak, the inverse inspiration of the stirring lines "The Lost Leader." Browning's strong sympathies with the Liberal cause are here portrayed with an ardor which is fairly intoxicating poetically, but one feels it is scarcely just to the mild-eyed, exemplary Wordsworth, and perhaps exaggeratedly sure of Shakespeare's attitude on this point. It is only fair to Browning, to point out how he himself felt later that his artistic mood had here run away with him, whereupon he made amends honorable in a letter in reply to the question whether he had Wordsworth in mind: "I can only answer, with something of shame and contrition, that I undoubtedly had Wordsworth in my mind—but simply as a model; you know an artist takes one or two striking traits in the features of his 'model,' and uses them to start his fancy on a flight which may end far enough from the good man or woman who happens to be sitting for nose and eye. I thought of the great Poet's abandonment of liberalism at an unlucky juncture, and no repaying consequence that I could ever see. But, once call my fancy-portrait Wordsworth—and how much more ought one to say!"

The defection of Wordsworth from liberal sympathies is one of the commonplaces of12 literary history. There was a time when he figured in his poetry as a patriotic leader of the people, when in clarion tones he exhorted his countrymen to "arm and combine in defense of their common birthright." But this was in the enthusiasm of his youth when he and Southey and Coleridge were metaphorically waving their red caps for the principles of the French Revolution. The unbridled actions of the French Revolutionists, quickly cooled off their ardor, and as Taine cleverly puts it, "at the end of a few years, the three, brought back into the pale of State and Church, were, Coleridge, a Pittite journalist, Wordsworth, a distributor of stamps, and Southey, poet-laureate; all converted zealots, decided Anglicans, and intolerant conservatives." The "handful of silver" for which the patriot in the poem is supposed to have left the cause included besides the post of "distributor of stamps," given to him by Lord Lonsdale in 1813, a pension of three hundred pounds a year in 1842, and the poet-laureateship in 1843.

The first of these offices was received so long after the cooling of Wordsworth's "Revolution" ardors which the events of 1793 had brought about that it can scarcely be said to have influenced his change of mind.

13It was during Wordsworth's residence in France, from November 1791 to December 1792, that his enthusiasm for the French Revolution reached white heat. How the change was wrought in his feelings is shown with much penetration and sympathy by Edward Dowden in his "French Revolution and English Literature." "When war between France and England was declared Wordsworth's nature underwent the most violent strain it had ever experienced. He loved his native land yet he could wish for nothing but disaster to her arms. As the days passed he found it more and more difficult to sustain his faith in the Revolution. First, he abandoned belief in the leaders but he still trusted to the people, then the people seemed to have grown insane with the intoxication of blood. He was driven back from his defense of the Revolution, in its historical development, to a bare faith in the abstract idea. He clung to theories, the free and joyous movement of his sympathies ceased; opinions stifled the spontaneous life of the spirit, these opinions were tested and retested by the intellect, till, in the end, exhausted by inward debate, he yielded up moral questions in despair ... by process of the understanding alone Wordsworth could attain no14 vital body of truth. Rather he felt that things of far more worth than political opinions—natural instincts, sympathies, passions, intuitions—were being disintegrated or denaturalized. Wordsworth began to suspect the analytic intellect as a source of moral wisdom. In place of humanitarian dreams came a deep interest in the joys and sorrows of individual men and women; through his interest in this he was led back to a study of the mind of man and those laws which connect the work of the creative imagination with the play of the passions. He had begun again to think nobly of the world and human life." He was, in fact, a more thorough Democrat socially than any but Burns of the band of poets mentioned in Browning's gallant company, not even excepting Browning himself.

Whether an artist is justified in taking the most doubtful feature of his model's physiognomy and building up from it a repellent portrait is question for debate, especially when he admits its incompleteness. But we16 may balance against this incompleteness, the fine fire of enthusiasm for the "cause" in the poem, and the fact that Wordsworth has not been at all harmed by it. The worst that has happened is the raising in our minds of a question touching Browning's good taste.

Just here it will be interesting to speak of a bit of purely personal expression on the subject of Browning's known liberal standpoint, written by him in answer to the question propounded to a number of English men of letters and printed together with other replies in a volume edited by Andrew Reid in 1885.

William Wordsworth

|

"How all our copper had gone for his service. |

17 Enthusiasm for liberal views comes out again and again in the poetry of Browning.

His fullest treatment of the cause of political liberty is in "Strafford," to be considered in the third chapter, but many are the hints strewn about his verse that bring home with no uncertain touch the fact that Browning lived man's "lover" and never man's "hater." Take as an example "The Englishman in Italy," where the sarcastic turn he gives to the last stanza shows clearly where his sympathies lie:

More the ordinary note of patriotism is struck in "Home-thoughts, from the Sea," wherein the scenes of England's victories as they come before the poet arouse pride in her military achievements.

In two instances Browning celebrates English friends in his poetry. The poems are "Waring" and "May and Death."

Waring, who stands for Alfred Domett, is an interesting figure in Colonial history as well as a minor light among poets. But it is highly probable that he would not have been put into verse by Browning any more than many other of the poet's warm friends if it had not been for the incident described in the poem which actually took place, and made a strong enough impression to inspire a creative if not exactly an exalted mood on Browning's part. The incident is recorded in Thomas Powell's "Living Authors of England," who writes of Domett, "We have a vivid recollection of the last time we saw him. It was at an evening party a few days before he sailed from England; his intimate friend, Mr. Browning, was also present. It happened that the latter was introduced that evening for the first time to a young author19 who had just then appeared in the literary world [Powell, himself]. This, consequently, prevented the two friends from conversation, and they parted from each other without the slightest idea on Mr. Browning's part that he was seeing his old friend Domett for the last time. Some days after when he found that Domett had sailed, he expressed in strong terms to the writer of this sketch the self-reproach he felt at having preferred the conversation of a stranger to that of his old associate."

This happened in 1842, when with no good-bys, Domett sailed for New Zealand where he lived for thirty years, and held during that time many important official posts. Upon his return to England, Browning and he met again, and in his poem "Ranolf and Amohia," published the year after, he wrote the often quoted line so aptly appreciative of Browning's genius,—"Subtlest assertor of the soul in song."

The poem belongs to the vers de société order, albeit the lightness is of a somewhat ponderous variety. It, however, has much interest as a character sketch from the life, and is said by those who had the opportunity of knowing to be a capital portrait.

Rydal Mount, the Home of Wordsworth

"May and Death" is perhaps more interesting for the glimpse it gives of Browning's appreciation of English Nature than for its expression of grief for the death of a friend.

The poet's one truly enthusiastic outburst in connection with English Nature he sings out in his longing for an English spring in the incomparable little lyric "Home-thoughts, from Abroad."

After this it seems hardly possible that Browning, himself speaks in "De Gustibus," yet long and happy living away from England doubtless dimmed his sense of the beauty of English landscape. "De Gustibus" was published ten years later than "Home-Thoughts from Abroad," when Italy and he had indeed become "lovers old." A deeper reason than mere delight in its scenery is also reflected in the poem; the sympathy shared with Mrs. Browning, for the cause of Italian independence.

Two or three English artists called forth appreciation in verse from Browning. There is the exquisite bit called "Deaf and Dumb," after a group of statuary by Woolner, of Constance and Arthur—the deaf and dumb children of Sir Thomas Fairbairn.

A GROUP BY WOOLNER.

An English Lane

There is also the beautiful description in "Balaustion's Adventure" of the Alkestis by Sir Frederick Leighton.

The flagrant anachronism of making a Greek girl at the time of the Fall of Athens describe an English picture cannot but be forgiven, since the artistic effect gained is so fine. The poet quite convinces the reader that Sir Frederick Leighton ought to have been a Kaunian painter, if he was not, and that Balaustion or no one was qualified to appreciate his picture at its full worth.

Once before had Sir Frederick Leighton inspired the poet in the exquisite lines on Eurydice.

A PICTURE BY LEIGHTON

Beautiful as these lines are, they do not impress me as fully interpreting Leighton's picture. The expression of Eurydice is rather one of unthinking confiding affection—as if she were really unconscious or ignorant of the danger; while that of Orpheus is one of passionate agony as he tries to hold her off.

Though English art could not fascinate the poet as Italian art did, for the fully sufficient reason that it does not stand for a great epoch of intellectual awakening, yet with what fair alchemy he has touched those few artists he has chosen to honor. Notwithstanding his avowed devotion to Italy, expressed in "De Gustibus," one cannot help feeling that in the poems mentioned in this chapter, there is that ecstasy of sympathy which goes only to the most potent influences in the formation of character. Something of what I mean is expressed in one of his latest poems, "Development." In this we certainly get a real peep at young Robert Browning, led by his wise father into the delights of Homer, by slow degrees, where all is truth at first, to36 end up with the devastating criticism of Wolf. In spite of it all the dream stays and is the reality. Nothing can obliterate the magic of a strong early enthusiasm, as "fact still held" "Spite of new Knowledge," in his "heart of hearts."

This chapter would not be complete without Browning's tribute to dog Tray, whose traits may not be peculiar to English dogs40 but whose name is proverbially English. Besides it touches a subject upon which the poet had strong feelings. Vivisection he abhorred, and in the controversies which were tearing the scientific and philanthropic world asunder in the last years of his life, no one was a more determined opponent of vivisection than he.

SHAKESPEARE'S PORTRAIT

Once and once only did Browning depart from his custom of choosing people of minor note to figure in his dramatic monologues. In "At the 'Mermaid'" he ventures upon the consecrated ground of a heart-to-heart talk between Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and the wits who gathered at the classic "Mermaid" Tavern in Cheapside, following this up with further glimpses into the inner recesses of Shakespeare's mind in the monologues "House" and "Shop." It is a particularly daring feat in the case of Shakespeare, for as all the world knows any attempt at getting in touch with the real man, Shakespeare, must, per force, be woven out of such "stuff as dreams are made on."

In interpreting this portraiture of one great poet by another it will be of interest to glance at the actual facts as far as they are known in regard to the relations which existed between Shakespeare and Jonson. Praise and blame both are recorded on Jon43son's part when writing of Shakespeare, yet the praise shows such undisguised admiration that the blame sinks into insignificance. Jonson's "learned socks" to which Milton refers probably tripped the critic up occasionally by reason of their weight.

There is a charming story told of the friendship between the two men recorded by Sir Nicholas L'Estrange, within a very few years of Shakespeare's death, who attributed it to Dr. Donne. The story goes that "Shakespeare was godfather to one of Ben Jonson's children, and after the christening, being in a deep study, Jonson came to cheer him up and asked him why he was so melancholy. 'No, faith, Ben,' says he, 'not I, but I have been considering a great while what should be the fittest gift for me to bestow upon my godchild, and I have resolved at last.' 'I prythee what?' says he. 'I'faith, Ben, I'll e'en give him a dozen good Lattin spoons, and thou shalt translate them.'" If this must be taken with a grain of salt, there is another even more to the honor of Shakespeare reported by Rowe and considered credible by such Shakespearian scholars as Halliwell Phillipps and Sidney Lee. "His acquaintance with Ben Jonson" writes Rowe, "began with a remarkable piece of humanity44 and good nature; Mr. Jonson, who was at that time altogether unknown to the world, had offered one of his plays to the players in order to have it acted, and the persons into whose hands it was put, after having turned it carelessly and superciliously over, were just upon returning it to him with an ill-natured answer that it would be of no service to their company, when Shakespeare luckily cast his eye upon it, and found something so well in it as to engage him first to read it through, and afterwards to recommend Mr. Jonson and his writings to the public." The play in question was the famous comedy of "Every Man in His Humour," which was brought out in September, 1598, by the Lord Chamberlain's company, Shakespeare himself being one of the leading actors upon the occasion.

Authentic history records a theater war in which Jonson and Shakespeare figured, on opposite sides, but if allusions in Jonson's play the "Poetaster" have been properly interpreted, their friendly relations were not deeply disturbed. The trouble began in the first place by the London of 1600 suddenly rushing into a fad for the company of boy players, recruited chiefly from the choristers of the Chapel Royal, and known as the "Chil45dren of the Chapel." They had been acting at the new theater in Blackfriars since 1597, and their vogue became so great as actually to threaten Shakespeare's company and other companies of adult actors. Just at this time Ben Jonson was having a personal quarrel with his fellow dramatists, Marston and Dekker, and as he received little sympathy from the actors, he took his revenge by joining his forces with those of the Children of the Chapel. They brought out for him in 1600 his satire of "Cynthia's Revels," in which he held up to ridicule Marston, Dekker and their friends the actors. Marston and Dekker, with the actors of Shakespeare's company, prepared to retaliate, but Jonson hearing of it forestalled them with his play the "Poetaster" in which he spared neither dramatists nor actors. Shakespeare's company continued the fray by bringing out at the Globe Theatre, in the following year, Dekker and Marston's "Satiro-Mastix, or The Untrussing of the Humorous Poet," and as Ward remarks, "the quarrel had now become too hot to last." The excitement, however, continued for sometime, theater-goers took sides and watched with interest "the actors and dramatists' boisterous war of personalities," to quote Mr. Lee, who46 goes on to point out that on May 10, 1601, the Privy Council called the attention of the Middlesex magistrates to the abuse covertly leveled by the actors of the "Curtain" at gentlemen "of good desert and quality," and directed the magistrates to examine all plays before they were produced.

Jonson, himself, finally made apologies in verses appended to printed copies of the "Poetaster."

Sidney Lee cleverly deduces Shakespeare's attitude in the quarrel in allusions to it in "Hamlet," wherein he "protested against the abusive comments on the men-actors of 'the common' stages or public theaters which were put into the children's mouths. Rosencrantz declared that the children 'so berattle47 [i.e. assail] the common stages—so they call them—that many wearing rapiers are afraid of goose-quills, and dare scarce come thither [i.e. to the public theaters].' Hamlet in pursuit of the theme pointed out that the writers who encouraged the vogue of the 'child actors' did them a poor service, because when the boys should reach men's estate they would run the risk, if they continued on the stage, of the same insults and neglect which now threatened their seniors.

"'Hamlet. What are they children? Who maintains 'em? How are they escorted [i.e. paid]? Will they pursue the quality [i.e. the actor's profession] no longer than they can sing? Will they not say afterwards, if they should grow themselves to common players—as it is most like, if their means are no better—their writers do them wrong to make them exclaim against their own succession?

"'Rosencrantz. Faith, there has been much to do on both sides, and the nation holds it no sin to tarre [i.e. incite] them to controversy; there was for a while no money bid for argument, unless the poet and the player went to cuffs in the question.'"

This certainly does not reflect a very belligerent attitude since it merely puts in a word for the grown-up actors rather than48 casting any slurs upon the children. Further indications of Shakespeare's mildness in regard to the whole matter are given in the Prologue to "Troylus and Cressida," where, as Mr. Lee says, he made specific reference to the strife between Ben Jonson and the players in the lines

The most interesting bit of evidence to show that Shakespeare and Jonson remained friends, even in the heat of the conflict, may be gained from the "Poetaster" itself if we admit that the Virgil of the play, who is chosen peacemaker stands for Shakespeare; and who so fit to be peacemaker as Shakespeare for his amiable qualities seem to have impressed themselves upon all who knew him.

Following Mr. Lee's lead, "Jonson figures personally in the 'Poetaster' under the name of Horace. Episodically Horace and his friends, Tibullus and Gallus, eulogize the work and genius of another character, Virgil, in terms so closely resembling those which Jonson is known to have applied to Shakespeare that they may be regarded as intended to apply to him (Act V, Scene I). Jonson points49 out that Virgil, by his penetrating intuition, achieved the great effects which others laboriously sought to reach through rules of art.

Tibullus gives Virgil equal credit for having in his writings touched with telling truth upon every vicissitude of human existence:

"Finally, Virgil in the play is nominated by Cæsar to act as judge between Horace and his libellers, and he advises the administration of purging pills to the offenders."

This neat little chain of evidence would have no weak link, if it were not for a passage in the play, "The Return from Parnassus,"50 acted by the students in St. John's College the same year, 1601. In this there is a dialogue between Shakespeare's fellow-actors, Burbage and Kempe. Speaking of the University dramatists, Kempe says:

"Why here's our fellow Shakespeare puts them all down; aye, and Ben Jonson, too. O! that Ben Jonson is a pestilent fellow. He brought up Horace, giving the poets a pill; but our fellow Shakespeare hath given him a purge that made him bewray his credit." Burbage continues, "He is a shrewd fellow indeed." This has, of course, been taken to mean that Shakespeare was actively against Jonson in the Dramatists' and Actors' war. But as everything else points, as we have seen, to the contrary, one accepts gladly the loophole of escape offered by Mr. Lee. "The words quoted from 'The Return from Parnassus' hardly admit of a literal interpretation. Probably the 'purge' that Shakespeare was alleged by the author of 'The Return from Parnassus' to have given Jonson meant no more than that Shakespeare had signally outstripped Jonson in popular esteem." That this was an actual fact is proved by the lines of Leonard Digges, an admiring contemporary of Shakespeare's, printed in the 1640 edition of Shakespeare's poems, com51paring "Julius Cæsar" and Jonson's play "Cataline:"

This reminds one of the famous witticism attributed to Eudymion Porter that "Shakespeare was sent from Heaven and Ben from College."

If Jonson's criticisms of Shakespeare's work were sometime not wholly appreciative, the fact may be set down to the distinction between the two here so humorously indicated. "A Winter's Tale" and the "Tempest" both called forth some sarcasms from Jonson, the first for its error about the Coast of Bohemia which Shakespeare borrowed from Greene. Jonson wrote in the Induction to "Bartholemew Fair;" "If there be never a servant-monster in the Fair, who can help it he says? Nor a nest of Antics. He is loth to make nature afraid in his plays like those that beget Tales, Tempests, and such like Drolleries." The allusions here are very evidently to Caliban and the satyrs who figure in52 the sheep-shearing feast in "A Winter's Tale." The worst blast of all, however, occurs in Jonson's "Timber," but the blows are evidently given with a loving hand. He writes "I remember, the players have often mentioned it as an honor to Shakespeare that, in his writing, whatsoever he penn'd, hee never blotted out line. My answer hath beene, would he had blotted a thousand;—which they thought a malevolent speech. I had not told posterity this, but for their ignorance who choose that circumstance to commend their friend by wherein he most faulted; and to justifie mine owne candor,—for I lov'd the man, and doe honor his memory, on this side idolatry, as much as any. Hee was, indeed, honest, and of an open and free nature; had an excellent phantasie; brave notions and gentle expressions; wherein hee flow'd with that facility that sometime it was necessary he should be stop'd;—sufflaminandus erat, as Augustus said of Haterius. His wit was in his owne power;—would the rule of it had beene so too! Many times he fell into those things, could not escape laughter; as when he said in the person of Cæsar, one speaking to him,—Cæsar thou dost me wrong; hee replyed,—Cæsar did never wrong but with just cause; and such like; which were53 ridiculous. But hee redeemed his vices with his virtues. There was ever more in him to be praysed then to be pardoned."

And even this criticism is altogether controverted by the wholly eulogistic lines Jonson wrote for the First Folio edition of Shakespeare printed in 1623, "To the memory of my beloved, The Author Mr. William Shakespeare and what he hath left us."[1]

For the same edition he also wrote the following lines for the portrait reproduced in this volume, which it is safe to regard as the Shakespeare Ben Jonson remembered:

Shakespeare's talk in "At the 'Mermaid'" grows out of the supposition, not touched upon54 until the very last line that Ben Jonson had been calling him "Next Poet," a supposition quite justifiable in the light of Ben's praises of him. The poem also reflects the love and admiration in which Shakespeare the man was held by all who have left any record of their impressions of him. As for the portraiture of the poet's attitude of mind, it is deduced indirectly from his work. That he did not desire to become "Next Poet" may be argued from the fact that after his first outburst of poem and sonnet writing in the manner of the poets of the age, he gave up the career of gentleman-poet to devote himself wholly to the more independent if not so socially distinguished one of actor-playwright. "Venus and Adonis" and "Lucrece" were the only poems of his published under his supervision and the only works with the dedication to a patron such as it was customary to write at that time.

I have before me as I write the recent Clarendon Press fac-similes of "Venus and Adonis" and "Lucrece," published respectively in 1593 and 1594,—beautiful little quartos with exquisitely artistic designs in the title-pages, headpieces and initials; altogether worthy of a poet who might have designs upon Fame. The dedication to the first reads:—

55

"to the right honorable

Henry Wriothesley, Earle of Southampton

and Baron of Litchfield

Right Honourable, I know not how I shall offend in dedicating my unpolisht lines to your Lordship, nor how the worlde will censure mee for choosing so strong a proppe to support so weake a burthen, onelye if your Honour seeme but pleased, I account my selfe highly praised, and vowe to take advantage of all idle houres, till I have honoured you with some great labour. But if the first heire of my invention prove deformed, I shall be sorie it had so noble a god-father: and never after eare so barren a land, for feare it yield me still so bad a harvest, I leave it to your Honourable Survey, and your Honor to your hearts content, which I wish may alwaies answere your owne wish, and the worlds hopeful expectation.

Your Honors in all dutie

William Shakespeare."

The second reads:—

"TO THE RIGHT

honorable, henry

Wriothesley, Earle of Southampton

and Baron of Litchfield

The love I dedicate to your Lordship is without end: wherof this Pamphlet without be56ginning is a superfluous Moiety. The warrant I have of your Honourable disposition, nor the worth of my untutored Lines makes it assured of acceptance. What I have done is yours, what I have to doe is yours, being part in all I have, devoted yours. Were my worth greater, my duety would shew greater, meane time, as it is, it is bound to your Lordship; To whom I wish long life still lengthened with all happinesse.

Your Lordships in all duety.

William Shakespeare."

No more after this does Shakespeare appear in the light of a poet with a patron. Even the sonnets, some of which evidently celebrate Southampton, were issued by a piratical publisher without Shakespeare's consent, while his plays found their way into print at the hands of other pirates who cribbed them from stage copies.

Such hints as these have been worked up by Browning into a consistent characterization of a man who regards himself as having foregone his chances of laureateship or "Next Poet" by devoting himself to a form of literary art which would not appeal to the powers that be as fitting him for any such position. Such honors he claims do not go to57 the dramatic poet, who has never allowed the world to slip inside his breast, but has simply portrayed the joy and the sorrow of life as he saw it around him, and with an art which turns even sorrow into beauty.—"Do I stoop? I pluck a posy, do I stand and stare? all's blue;"—but to the subjective, introspective poet, out of tune with himself and with the universe. The allusions Shakespeare makes to the last "King" are not very definite, but, on the whole, they fit Edmund Spenser, whose poems from first to last are dedicated to people of distinction in court circles. His work, moreover, is full of wailing and woe in various keys, and also full of self-revelation. He allowed the world to slip inside his breast upon almost every occasion, and perhaps he may be said to have bought "his laurel," for it was no doubt extremely gratifying to Queen Elizabeth to see herself in the guise of the Faerie Queene, and even his dedication of the "Faerie Queene" to her, used as she was to flattery, must have been as music in her ears. "To the most high, mightie, and magnificent Empresse, renouned for piety, vertue, and all gratious government, Elizabeth, by the Grace of God, Queene of England, Frahnce, and Ireland and of Virginia. Defender of the Faith, &c. Her most humble servant Edmund58 Spenser doth in all humilitie, Dedicate, present, and consecrate These his labours, To live with the eternity of her Fame." The next year Spenser received a pension from the crown of fifty pounds per annum.

It is a careful touch on Browning's part to use the phrase "Next Poet," for the "laureateship" at that time was not a recognized official position. The term, "laureate," seems to have been used to designate poets who had attained fame and Royal favor, since Nash speaks of Spenser in his "Supplication of Piers Pennilesse" the same year the "Faerie Queene" was published as next laureate.

The first really officially appointed Poet Laureate was Ben Jonson, himself, who in either 1616 or 1619 received the post from James I., later ratified by Charles I., who increased the annuity to one hundred pounds a year and a butt of wine from the King's cellars.

Probably the allusion "Your Pilgrim" in the twelfth stanza of "At the Mermaid" is to "The Return from Parnassus" in which the pilgrims to Parnassus who figure in an earlier play "The Pilgrimage to Parnassus" discover the world to be about as dismal a place as it is described in this stanza.

At first sight it might seem that the position59 taken by Shakespeare in the poem is almost too modest, yet upon second thoughts it will be remembered that though Shakespeare had a tremendous following among the people, attested by the frequency with which his plays were acted; that though there are instances of his being highly appreciated by contemporaries of importance; that though his plays were given before the Queen, he did not have the universal acceptance among learned and court circles which was accorded to Spenser.

It is quite fitting that the scene should be set in the "Mermaid." No record exists to show that Shakespeare was ever there, it is true, but the "Mermaid" was a favorite haunt of Ben Jonson and his circle of wits, whose meetings there were immortalized by Beaumont in his poetical letter to Jonson:—

Add to this what Fuller wrote in his "Worthies," 1662, "Many were the wit-combats betwixt him and Ben Jonson, which60 two I behold like a Spanish great galleon and an English man-of-war; Master Jonson (like the former) was built far higher in learning, solid but slow in his performances. Shakespeare, with the English man-of-war, lesser in bulk, but lighter in sailing, could turn with all tides, tack about, and take advantage of all winds by the quickness of his wit and invention," and there is sufficient poetic warrant for the "Mermaid" setting.

First Folio Portrait of Shakespeare

|

"Do I stoop? I pluck a posy. |

The final touch is given in the hint that all the time Shakespeare is aware of his own greatness, perhaps to be recognized by a future age.

Let Browning, himself, now show what he has done with the material.

The first stanza of "House"—

brings one face to face with the interminable controversies upon the autobiographical significance of Shakespeare's Sonnets. As volumes upon the subject have been written, it is not possible even adequately to review the various theories here. The controversialists may be broadly divided into those who read complicated autobiographical details into the sonnets, those who scout the idea of their being autobiographical at all, and those who take a middle ground. Of the first there are two factions: one of these believes that the opening sonnets were addressed to Lord William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, and the other that they were addressed to Shakespeare's patron, the Earl of Southampton. The first theory dates back as far as 1832 when it was started by James Boaden, a journalist and the biographer of67 Kemble and Mrs. Siddons. This theory has had many supporters and is associated to-day with the name of Thomas Tyler, who, in his edition of the Sonnets published in 1890, claimed to have identified the dark lady of the Sonnets with a lady of the Court, Mary Fitton and the mistress of the Earl of Pembroke. The theory, like most things of the sort, has its fascinations, and few people can read the Sonnets without being more or less impressed by it. It is based, however, upon a supposition so unlikely that it may be said to be proved incorrect, namely, that the dedication of the Sonnets to their "Onlie Begettor, Mr. W. H." is intended for "Mr. William Herbert." There was a Mr. William Hall, later a master printer, and the friend of Thomas Thorpe, the publisher of the Sonnets, who is much more likely to be the person meant. Lord Herbert was far too important a person to be addressed as Mr. W. H. As Mr. Lee points out, when Thorpe did dedicate books to Herbert he was careful to give full prominence to the titles and distinction of his patron. The Sonnets as we have already seen were not published with Shakespeare's sanction. In those days the author had no protection, and if a manuscript fell into the hands of a printer he could print it if he felt68 so disposed. Mr. William Hall was in the habit of looking out for manuscripts and before he became a printer, in 1606, had one published by Southwell of which he himself wrote the dedication, to the "Vertuous Gentleman, Mathew Saunders, Esquire W. H. wisheth, with long life, a prosperous achievement of his good desires." "There is little doubt," writes Mr. Lee, "that the W. H. of the Southwell volume was Mr. William Hall, who, when he procured that manuscript for publication, was an humble auxiliary in the publishing army." To sum up in Mr. Lee's words his interesting and convincing chapter on "Thomas Thorpe and Mr. 'W. H.'" "'Mr. W. H.,' whom Thorpe described as the 'only begetter of these ensuing sonnets,' was in all probability the acquirer or procurer of the manuscript, who, figuratively speaking, brought the book into being either by first placing the manuscript in Thorpe's hands or by pointing out the means by which a copy might be acquired. To assign such significance to the word 'begetter' was entirely in Thorpe's vein. Thorpe described his rôle in the piratical enterprise of the 'Sonnets' as that of 'the well-wishing adventurer in setting forth,' i.e., the hopeful speculator in the scheme. 'Mr. W. H.' doubtless69 played the almost equally important part—one as well known then as now in commercial operations—of the 'vender' of the property to be exploited."

The Southampton theory is reared into a fine air-castle by Gerald Massey in his lengthy book on the Sonnets—truly entertaining reading but too ingenious to be convincing.

Finally Mr. Lee in his book looks at the subject in an unbiased and perfectly sane way. He thinks the opening Sonnets are to the Earl of Southampton, known to be Shakespeare's patron, but he warns us that exaggerated devotion was the hall-mark of the Sonnets of the age, and therefore what Shakespeare says of his young patron in these Sonnets need not be taken too literally as expressing the poet's sentiments, though he admits there may be a note of genuine feeling in them. Also he thinks that some of the sonnets reflecting moods of melancholy or a sense of sin may reveal the writer's inner consciousness. Possibly, too, the story of the "dark lady" may have some basis in fact, though he insists, "There is no clue to the lady's identity, and speculation on the topic is useless." Furthermore, he thinks it doubtful whether all the words in these Sonnets are to be taken with the seriousness implied, the affair70 probably belonging only to the annals of gallantry.

It will be seen from the poem that Browning took the uncompromisingly non-autobiographical view of the Sonnets. In this stand present authoritative opinion would not justify him, but it speaks well for his insight and sympathy that he was not fascinated by the William Herbert theory which, at the time he wrote the poem, was very much in the air.

In "Shop" is given, in a way, the obverse side of the idea. If it is proved that the dramatic poet does not allow himself to appear in his work, the step toward regarding him as having no individuality aside from his work is an easy one. The allusions in the poem to the mercenariness of the "Shop-Keeper" seem to hit at the criticisms of Shakespeare's thrift, which enabled him to buy a home in his native place and retire there to live some years before the end of his life. In some quarters it has been customary to regard Shakespeare as devoting himself to dramatic literature in order to make money, as if this were a terrible slur on his character. The superiority of such an independent spirit over that of those who constantly sought patrons was quite manifest to Browning's mind or he would not have written this sarcastic bit of71 symbolism, between the lines of which can be read that Browning was on Shakespeare's side.

These poems are valuable not only for furnishing an interesting interpretation of Shakespeare's character as a man and artist, but for the glimpses they give into Browning's stand toward his own art. He wished to be regarded primarily as a dramatic artist, presenting and interpreting the souls of his characters, and he must have felt keenly the stupid attitude which insisted always in reading "Browning's Philosophy" into all his poems. The fact that his objective material was of the soul rather than of the external actions of life has no doubt lent force to the supposition that Browning himself can be seen in everything he writes. It is true, nevertheless, that while much of his work is Shakespearian in its dramatic intensity, he had too forceful a philosophy of life to keep it from sometimes coming to the front. Besides he78 has written many things avowedly personal as this chapter amply illustrates.

To what intensity of feeling Browning could rise when contemplating the genius of Shakespeare is revealed in his direct and outspoken tribute. Here there breathes an almost reverential attitude toward the one supremely great man he has ventured to portray.

A CRUCIAL PERIOD IN ENGLISH HISTORY

"Whom the gods destroy they first make mad." Of no one in English history is this truer than of King Charles I. Just at a time when the nation was feeling the strength of its wings both in Church and State, when individuals were claiming the right to freedom of conscience in their form of worship and the people were growing more insistent for the recognition of their ancient rights and liberties, secured to them, in the first place, by the Magna Charta,—just at this time looms up the obstruction of a King so imbued with the defunct ideal of the divine right of Kings that he is blind to the tendencies of the age. What wonder, then, if the swirling waters of discontent should rise higher and higher until he became engulfed in their fury.

The history of the reign of Charles I. is one full of involved details, yet the broader aspects of it, the great events which chiseled into shape the future of England stand out80 in bold relief in front of a background of interminable bickerings. There was constant quarreling between the factions within the English church, and between the Protestants and the Catholics, complicated by the discontent of the people and at times the nobles because of the autocratic, vacillating policy of the King.

Among these epoch-bringing events were the emergence of the Puritans from the chaos of internecine church squabbles, the determined raising of the voice of the people in the Long Parliament, where King and people finally came to an open clash in the impeachment of the King's most devoted minister, Wentworth, Earl Strafford, by Pym, the great leader in the House of Commons, ending in Strafford's execution; the Grand Remonstrance, which sounded in no uncertain tones the tocsin of the coming revolution; and finally the King's impeachment of Pym, Hampden, Holles, Hazelrigg and Strode, one of the many ill-advised moves of this Monarch which at once precipitated the Revolution.

These cataclysms at home were further intensified by the Scottish Invasion and the Irish Rebellion.

Charles I in Scene of Impeachment

It is not surprising that Browning should81 have been attracted to this period of English history, when he contemplated the writing of a play on an English subject. His liberty-loving mind would naturally find congenial occupation in depicting this great English struggle for liberty. Yet the hero of the play is not Pym, the leader of the people, but Strafford, the supporter of the King. The dramatic reasons are sufficient to account for this. Strafford's career was picturesque and tragic and his personality so striking that more than one interpretation of his remarkable life is possible.

The interpretation will differ according to whether one is partisan in hatred or admiration of his character and policy, or possesses the larger quality of sympathetic appreciation of the man and the problems with which he had to deal. Any one coming to judge him in this latter spirit would undoubtedly perceive all the fine points in Strafford's nature and would balance these against his theories of government to the better understanding of this extraordinary man.

It is almost needless to say that Browning's perception of Strafford's character was penetrating and sympathetic. Strafford's devotion to his King had in it not only the element of loyalty to the liege, but an element82 of personal love which would make an especial appeal to Browning. He, in consequence, seizes upon this trait as the key-note of his portrayal of Strafford.

The play is, on the whole, accurate in its historical details, though the poet's imagination has added many a flying buttress to the structure.

Forster's lives of the English Statesmen in Lardner's Cyclopædia furnished plenty of material, and he was besides familiar with some if not all of Forster's materials for the lives. One of the interesting surprises in connection with Browning's literary career was the fact divulged some years ago that he had actually helped Forster in the preparation of the Life of Strafford. Indeed it is thought that he wrote it almost entirely from the notes of Forster. Dr. Furnivall first called attention to this, and later the life of Strafford was reprinted as "Robert Browning's Prose Life of Strafford."[2] In his Forewords to this volume, Dr. Furnivall, who, among many other claims to distinction, was the president of the "London Browning Society," writes, "Three times during his life did Browning speak to me about his prose 'Life of Strafford.' The first time he said83 only—in the course of chat—that very few people had any idea of how much he had helped John Forster in it. The second time he told me at length that one day he went to see Forster and found him very ill, and anxious about the 'Life of Strafford,' which he had promised to write at once, to complete a volume of 'Lives of Eminent British Statesmen' for Lardner's 'Cabinet Cyclopædia.' Forster had finished the 'Life of Eliot'—the first in the volume—and had just begun that of Strafford, for which he had made full collections and extracts; but illness had come on, he couldn't work, the book ought to be completed forthwith, as it was due in the serial issue of volumes; what was he to do? 'Oh,' said Browning, 'don't trouble about it. I'll take your papers and do it for you.' Forster thanked his young friend heartily, Browning put the Strafford papers under his arm, walked off, worked hard, finished the Life, and it came out to time in 1836, to Forster's great relief, and passed under his name." Professor Gardiner, the historian, was of the opinion from internal evidence that the Life was more Browning's than Forster's. He said to Furnivall, "It is not a historian's conception of the character but a poet's. I am certain that it's not Forster's. Yes, it84 makes mistakes in facts and dates, but, it has got the man—in the main." In this opinion Furnivall concurs. Of the last paragraph in the history he exclaims, "I could swear it was Browning's":—The paragraph in question sums up the character of Strafford and is interesting in this connection, as giving hints, though not the complete picture of the Strafford of the Drama.

"A great lesson is written in the life of this truly extraordinary person. In the career of Strafford is to be sought the justification of the world's 'appeal from tyranny to God.' In him Despotism had at length obtained an instrument with mind to comprehend, and resolution to act upon, her principles in their length and breadth,—and enough of her purposes were effected by him, to enable mankind to 'see as from a tower the end of all.' I cannot discern one false step in Strafford's public conduct, one glimpse of a recognition of an alien principle, one instance of a dereliction of the law of his being, which can come in to dispute the decisive result of the experiment, or explain away its failure. The least vivid fancy will have no difficulty in taking up the interrupted design, and by wholly enfeebling, or materially emboldening, the insignificant nature of Charles; and by accord85ing some half-dozen years of immunity to the 'fretted tenement' of Strafford's 'fiery soul',—contemplate then, for itself, the perfect realization of the scheme of 'making the prince the most absolute lord in Christendom.' That done,—let it pursue the same course with respect to Eliot's noble imaginings, or to young Vane's dreamy aspirings, and apply in like manner a fit machinery to the working out the projects which made the dungeon of the one a holy place, and sustained the other in his self-imposed exile.—The result is great and decisive! It establishes, in renewed force, those principles of political conduct which have endured, and must continue to endure, 'like truth from age to age.'" The history, on the whole, lacks the grasp in the portrayal of Wentworth to be found in the drama. C. H. Firth, commenting upon this says truly, "One might almost say that in the first, Strafford was represented as he appeared to his opponents, and in the second as he appeared to himself; or that, having painted Strafford as he was, Browning painted him again as he wished to be. In the biography Strafford is exhibited as a man of rare gifts and noble qualities; yet in his political capacity, merely the conscious, the devoted tool of a tyrant. In the tragedy, on the other86 hand, Strafford is the champion of the King's will against the people's, but yet looks forward to the ultimate reconciliation of Charles and his subjects, and strives for it after his own fashion. He loves the master he serves, and dies for him, but when the end comes he can proudly answer his accusers, 'I have loved England too.'"

The play opens at the important moment of Wentworth's return to London from Ireland, where for some time he had been governor. The occasion of his return, according to Gardiner, was a personal quarrel with the Chancellor Loftus, of Ireland. Both men were allowed to come to England to plead their cause, which resulted in the victory of Wentworth. In the play Pym says, "Ay, the Court gives out His own concerns have brought him back: I know 'tis the King calls him." The authority for this remark is found in the Forster-Browning Life. "In the danger threatened by the Scots' Covenant, Wentworth was Charles's only hope; the King sent for him, saying he desired his personal counsel and attendance. He wrote: 'The Scots' Covenant begins to spread too far, yet, for all this, I will not have you take notice that I have sent for you, but pretend some other occasion of business.'" Certain it is that from this time Wentworth87 became the most trusted counsellor of Charles, that is, as far as Charles was capable of trusting any one. The condition of affairs to which Wentworth returned is brought out in the play in a thoroughly alive and human manner. We are introduced to the principal actors in the struggle for their rights and privileges against the government of Charles meeting in a house near Whitehall. Among the "great-hearted" men are Hampden, Hollis, the younger Vane, Rudyard, Fiennes—all leaders in the "Faction,"—Presbyterians, Loudon and other members of the Scots' commissioners. A bit of history has been drawn upon for this opening scene, for according to the Forster-Browning Life, "There is no doubt that a close correspondence with the Scotch commissioners, headed by Lords Loudon and Dumferling, was entered into under the management of Pym and Hampden. Whenever necessity obliged the meetings to be held in London, they took place at Pym's house in Gray's Inn Lane." In the talk between these men the political situation in England at the time from the point of view of the liberal party is brought vividly before the reader.

There has been no Parliament in England for ten years, hence the people have had no88 say in the direction of the government. The growing dissatisfaction of the people at being thus deprived of their rights focussed itself upon the question of "ship-money." The taxes levied by the King for the maintainance of a fleet were loudly objected to upon all sides. That a fleet was a necessary means of protection in those threatening times is not to be doubted, but the objections of the people were grounded upon the fact that the King levied these taxes upon his own authority. "Ship-money, it was loudly declared," says Gardiner, "was undeniably a tax, and the ancient customs of the realm, recently embodied in the Petition of Right, had announced with no doubtful voice that no tax could be levied without consent of Parliament. Even this objection was not the full measure of the evil. If Charles could take this money without the consent of Parliament, he need not, unless some unforeseen emergency arose, ever summon a Parliament again. The true question at issue was whether Parliament formed an integral part of the Constitution or not." Other taxes were objected to on the same grounds, and the more determined the King was not to summon a Parliament, the greater became the political ferment.

Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford

At the same time the religious ferment was89 centering itself upon hatred of Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury. His policy was to silence opposition to the methods of worship then followed by the Church of England, by the terrors of the Star Chamber. The Puritans were smarting under the sentence which had been passed upon the three pamphleteers, William Prynne, Henry Burton, and John Bastwick, who had expressed their opinions of the practises of the church with great outspokenness. Prynne called upon pious King Charles "to do justice on the whole Episcopal order by which he had been robbed of the love of God and of his people, and which aimed at plucking the crown from his head, that they might set it on their own ambitious pates." Burton hinted that "the sooner the office of the Bishops was abolished the better it would be for the nation." Bastwick, who had been brought up in the straitest principles of Puritanism, had ended his pamphlet "Flagellum Pontificis," with this outburst, "Take notice, so far am I from flying or fearing, as I resolve to make war against the Beast, and every hint of Antichrist, all the days of my life. If I die in that battle, so much the sooner I shall be sent in a chariot of triumph to heaven; and when I come there, I will, with those that are under the altar cry,90 'How long, Lord, holy and true, dost Thou not judge and avenge our blood upon them that dwell upon the earth?'"

These men were called before the Star Chamber upon a charge of libel. The sentence was a foregone conclusion, and was so outrageous that its result could only be the strengthening of opposition. The "muckworm" Cottington, as Browning calls him, suggested the sentence which was carried out. The men were condemned to lose their ears, to pay a fine of £5000 each, and to be imprisoned for the remainder of their lives in the castles of Carnarvon, Launceston, and Lancaster. Finch, not satisfied with this, added the savage wish that Prynne should be branded on the cheek with the letters S. L., to stand for "seditious libeller," and this was also done.

The account of the execution of this sentence is almost too horrible to read. Some one who recorded the scene wrote, "The humours of the people were various; some wept, some laughed, and some were very reserved." Prynne, whose sufferings had been greatest for he had been burned as well as having his ears taken off, was yet able to indulge in a grim piece of humor touching the letters S. L. branded on his cheeks. He91 called them "Stigmata Laudis," the "Scars of Laud," on his way back to prison. Popular demonstrations in favor of the prisoners were made all along the road when they were taken to their respective prisons, where they were allowed neither pen, ink nor books. Fearful lest they might somehow still disseminate their heretical doctrines to the outer world, the council removed them to still more distant prisons, in the Scilly Isles, in Guernsey and in Jersey. Retaliation against this treatment found open expression. "A copy of the Star Chamber decree was nailed to a board. Its corners were cut off as the ears of Laud's victims had been cut off at Westminster. A broad ink mark was drawn round Laud's name. An inscription declared that 'The man that puts the saints of God into a pillory of wood stands here in a pillory of ink!'"

Things were brought to a crisis in Scotland also, through hatred of Laud and the new prayer-book. The King, upon his visit to Scotland, had been shocked at the slovenly appearance and the slovenly ritual of the Scottish Church, which reflected strongly survivals of the Presbyterianism of an earlier time. The King wrote to the Scottish Bishops soon after his return to England: "We, tendering the good and peace of that Church by92 having good and decent order and discipline observed therein, whereby religion and God's worship may increase, and considering that there is nothing more defective in that Church than the want of a Book of Common Prayer and uniform service to be kept in all the churches thereof, and the want of canons for the uniformity of the same, we are hereby pleased to authorise you as the representative body of that Church, and do herewith will and require you to condescend upon a form of Church service to be used therein, and to set down the canons for the uniformity of the discipline thereof." Laud, who as Archbishop of Canterbury had no jurisdiction over Scottish Bishops, put his finger into the pie as secretary of the King. As Gardiner says, "He conveyed instructions to the Bishops, remonstrated with proceedings which shocked his sense of order, and held out prospects of advancement to the zealous. Scotchmen naturally took offense. They did not trouble themselves to distinguish between the secretary and the archbishop. They simply said that the Pope of Canterbury was as bad as the Pope of Rome."

The upshot of it all was that in May, 1637, the "new Prayer-book" was sent to Scotland, and every minister was ordered to buy two93 copies on pain of outlawry. Riots followed. It was finally decided that it must be settled once for all whether a King had any right to change the forms of worship without the sanction of a legislative assembly. Then came the Scottish Covenant which declared the intention of the signers to uphold religious liberty. The account of the signing of this covenant is one of the most impressive episodes in all history. The Covenant was carried on the 28th of February, 1638, to the Grey Friars' Church to which all the gentlemen present in Edinburgh had been summoned. The scene has been most sympathetically described by Gardiner.

"At four o'clock in the grey winter evening, the noblemen, the Earl of Sutherland leading the way began to sign. Then came the gentlemen, one after the other until nearly eight. The next day the ministers were called on to testify their approval, and nearly three hundred signatures were obtained before night. The Commissioners of the boroughs signed at the same time.

"On the third day the people of Edinburgh were called on to attest their devotion to the cause which was represented by the Covenant. Tradition long loved to tell how the honored parchment, carried back to the Grey Friars,94 was laid out on a tombstone in the churchyard, whilst weeping multitudes pressed round in numbers too great to be contained in any building. There are moments when the stern Scottish nature breaks out into an enthusiasm less passionate, but more enduring, than the frenzy of a Southern race. As each man and woman stepped forward in turn, with the right hand raised to heaven before the pen was grasped, every one there present knew that there would be no flinching amongst that band of brothers till their religion was safe from intrusive violence.

"Modern narrators may well turn their attention to the picturesqueness of the scene, to the dark rocks of the Castle crag over against the churchyard, and to the earnest faces around. The men of the seventeenth century had no thought to spare for the earth beneath or for the sky above. What they saw was their country's faith trodden under foot, what they felt was the joy of those who had been long led astray, and had now returned to the Shepherd and Bishop of their souls."

Such were the conditions that brought on the Scotch war, neither Charles nor Wentworth being wise enough to make concessions to the Covenanters.

95 The grievances against the King's Minister Wentworth are in this opening scene shown as being aggravated by the fact that the men of the "Faction" regard him as a deserter from their cause, Pym, himself being one of the number who is loth to think Wentworth stands for the King's policy.

The historical ground for the assumption lies in the fact that Wentworth was one of the leaders of the opposition in the Parliament of 1628.

The reason for this was largely personal, because of Buckingham's treatment of him. Wentworth had refused to take part in the collection of the forced loan of 1626, and was dismissed from his official posts in consequence. When he further refused to subscribe to that loan himself he was imprisoned in the Marshalsea and at Depford. Regarding himself as personally attacked by Buckingham, he joined the opposition. Yet, as Firth points out, "fiercely as he attacked the King's ministers, he was careful to exonerate the King." He concludes his list of grievances by saying, "This hath not been done by the King, but by projectors." Again, "Whether we shall look upon the King or his people, it did never more behove this great physician the parliament, to effect a true96 consent amongst the parties than now. Both are injured, both to be cured. By one and the same thing hath the King and people been hurt. I speak truly both for the interest of the King and the people."

His intention was to find some means of cooperation which would leave the people their liberty and yet give the crown its prerogative, "Let us make what laws we can, there must—nay, there will be a trust left in the crown."

It will be seen by any unbiased critic that Wentworth was only half for the people even at this time. On the other hand, it is not astonishing that men, heart and soul for the people, should consider Wentworth's subsequent complete devotion to the cause of the King sufficient to brand him as an apostate. The fact that he received so many official dignities from the King also leant color to the supposition that personal ambition was a leading motive with him. With true dramatic instinct Browning has centered this feeling and made the most of it in the attitude of Pym's party, while he offsets it later in the play by showing us the reality of the man Strafford.

There is no very authentic source for the idea also brought out in this first scene that97 Strafford and Pym had been warm personal friends. The story is told by Dr. James Welwood, one of the physicians of William III., who, in the year 1700, published a volume entitled "Memoirs, of the most material transactions in England for the last hundred years preceding the Revolution of 1688." Without mentioning any source he tells the following story; "There had been a long and intimate friendship between Mr. Pym and him [Wentworth], and they had gone hand in hand in everything in the House of Commons. But when Sir Thomas Wentworth was upon making his peace with the Court, he sent to Pym to meet him alone at Greenwich; where he began in a set speech to sound Mr. Pym about the dangers they were like to run by the courses they were in; and what advantages they might have if they would but listen to some offers which would probably be made them from the Court. Pym understanding his speech stopped him short with this expression: 'You need not use all this art to tell me you have a mind to leave us; but remember what I tell you, you are going to be undone. But remember, that though you leave us now I will never leave you while your head is upon your shoulders.'"

98 Though only a tradition this was entirely too useful a suggestion not to be used. The intensity of the situation between the leaders on opposite sides is enhanced tenfold by bringing into the field a personal sentiment.

The attitude of Pym's followers is reflected again in their opinion of Wentworth's Irish rule. Although Wentworth's policy seemed to be successful in Ireland, the very fact of its success would condemn it in the eyes of the popular party; besides later developments revealed its weaknesses. How it appeared to the eyes of a non-fanatical observer at this time may be gathered from the following letter of Sir Thomas Roe to the Queen of Bohemia, written in 1634.

"The Lord Deputy of Ireland doth great wonders, and governs like a King, and hath taught that Kingdom to show us an example of envy, by having parliaments, and knowing wisely how to use them; for they have given the King six subsidies, which will arise to £240,000, and they are like to have the liberty we contended for, and grace from his Majesty worth their gift double; and which is worth much more, the honor of good intelligence and love between the King and people, which I would to God our great wits had had eyes99 to see. This is a great service, and to give your Majesty a character of the man,—he is severe abroad and in business, and sweet in private conversation; retired in his friendships, but very firm; a terrible judge and a strong enemy; a servant violently zealous in his Master's ends, and not negligent of his own; one that will have what he will, and though of great reason, he can make his will greater when it may serve him; affecting glory by a seeming contempt; one that cannot stay long in the middle region of fortune, being entreprenant; but will either be the greatest man in England, or much less than he is; lastly, one that may (and his nature lies fit for it, for he is ambitious to do what others will not), do your Majesty very great service, if you can make him."

In order to be in sympathy with the play throughout and especially with the first scene all this historical background must be kept in mind, for the talk gives no direct information, it merely in an absolutely dramatic fashion reveals the feelings and opinions of the men upon the situation, just as friends at a dinner party might discuss one of our own less strenuous political situations—all present being perfectly familiar with the issues at stake.

Hampden, Hollis, the younger Vane, Rudyard, Fiennes and many of the Presbyterian Party: Loudon and other Scots' Commissioners.

Vane. I say, if he be here—

Rudyard. (And he is here!)—

Hollis. For England's sake let every man be still

Nor speak of him, so much as say his name,

Till Pym rejoin us! Rudyard! Henry Vane!

One rash conclusion may decide our course

And with it England's fate—think—England's fate!

Hampden, for England's sake they should be still!

Vane. You say so, Hollis? Well, I must be still.

It is indeed too bitter that one man,

Any one man's mere presence, should suspend

England's combined endeavor: little need

To name him!

Rudyard. For you are his brother, Hollis!

Hampden. Shame on you, Rudyard! time to tell him that,

When he forgets the Mother of us all.

Rudyard. Do I forget her?

Hampden. You talk idle hate

Against her foe: is that so strange a thing?

Is hating Wentworth all the help she needs?

A Puritan. The Philistine strode, cursing as he went:

But David—five smooth pebbles from the brook

Within his scrip....

Rudyard. Be you as still as David!

Fiennes. Here's Rudyard not ashamed to wag a tongue

101Stiff with ten years' disuse of Parliaments;

Why, when the last sat, Wentworth sat with us!

Rudyard. Let's hope for news of them now he returns—

He that was safe in Ireland, as we thought!

—But I'll abide Pym's coming.

Vane. Now, by Heaven,

They may be cool who can, silent who will—

Some have a gift that way! Wentworth is here,

Here, and the King's safe closeted with him

Ere this. And when I think on all that's past

Since that man left us, how his single arm

Rolled the advancing good of England back

And set the woeful past up in its place,

Exalting Dagon where the Ark should be,—

How that man has made firm the fickle King

(Hampden, I will speak out!)—in aught he feared

To venture on before; taught tyranny

Her dismal trade, the use of all her tools,

To ply the scourge yet screw the gag so close

That strangled agony bleeds mute to death;

How he turns Ireland to a private stage

For training infant villanies, new ways

Of wringing treasure out of tears and blood,

Unheard oppressions nourished in the dark

To try how much man's nature can endure

—If he dies under it, what harm? if not,

Why, one more trick is added to the rest

Worth a king's knowing, and what Ireland bears

England may learn to bear:—how all this while

That man has set himself to one dear task,

The bringing Charles to relish more and more

Power, power without law, power and blood too

—Can I be still?

Hampden. For that you should be still.

102

Vane. Oh Hampden, then and now! The year he left us,

The People in full Parliament could wrest

The Bill of Rights from the reluctant King;

And now, he'll find in an obscure small room

A stealthy gathering of great-hearted men

That take up England's cause: England is here!

Hampden. And who despairs of England?

Rudyard. That do I,

If Wentworth comes to rule her. I am sick

To think her wretched masters, Hamilton,

The muckworm Cottington, the maniac Laud,

May yet be longed-for back again. I say,

I do despair.

Vane. And, Rudyard, I'll say this—

Which all true men say after me, not loud

But solemnly and as you'd say a prayer!

This King, who treads our England underfoot,

Has just so much ... it may be fear or craft,

As bids him pause at each fresh outrage; friends,

He needs some sterner hand to grasp his own,

Some voice to ask, "Why shrink? Am I not by?"

Now, one whom England loved for serving her,

Found in his heart to say, "I know where best

The iron heel shall bruise her, for she leans

Upon me when you trample." Witness, you!

So Wentworth heartened Charles, so England fell.

But inasmuch as life is hard to take

From England....

Many Voices. Go on, Vane! 'Tis well said, Vane!

Vane. —Who has not so forgotten Runnymead!—

Voices. 'Tis well and bravely spoken, Vane! Go on!

Vane. —There are some little signs of late she knows

The ground no place for her. She glances round,

Wentworth has dropped the hand, is gone his way

103On other service: what if she arise?

No! the King beckons, and beside him stands

The same bad man once more, with the same smile

And the same gesture. Now shall England crouch,

Or catch at us and rise?

Voices. The Renegade!

Haman! Ahithophel!

Hampden. Gentlemen of the North,

It was not thus the night your claims were urged,

And we pronounced the League and Covenant,

The cause of Scotland, England's cause as well:

Vane there, sat motionless the whole night through.

Vane. Hampden!

Fiennes. Stay, Vane!

Loudon. Be just and patient, Vane!

Vane. Mind how you counsel patience, Loudon! you

Have still a Parliament, and this your League

To back it; you are free in Scotland still:

While we are brothers, hope's for England yet.

But know you wherefore Wentworth comes? to quench

This last of hopes? that he brings war with him?

Know you the man's self? what he dares?

Loudon. We know,

All know—'tis nothing new.

Vane. And what's new, then,

In calling for his life? Why, Pym himself—

You must have heard—ere Wentworth dropped our cause

He would see Pym first; there were many more

Strong on the people's side and friends of his,

Eliot that's dead, Rudyard and Hampden here,

But for these Wentworth cared not; only, Pym

He would see—Pym and he were sworn, 'tis said,

To live and die together; so, they met

At Greenwich. Wentworth, you are sure, was long,

104Specious enough, the devil's argument

Lost nothing on his lips; he'd have Pym own

A patriot could not play a purer part

Than follow in his track; they two combined

Might put down England. Well, Pym heard him out;

One glance—you know Pym's eye—one word was all:

"You leave us, Wentworth! while your head is on,

I'll not leave you."

Hampden. Has he left Wentworth, then?

Has England lost him? Will you let him speak,

Or put your crude surmises in his mouth?

Away with this! Will you have Pym or Vane?

Voices. Wait Pym's arrival! Pym shall speak.

Hampden. Meanwhile

Let Loudon read the Parliament's report

From Edinburgh: our last hope, as Vane says,

Is in the stand it makes. Loudon!

Vane. No, no!

Silent I can be: not indifferent!

Hampden. Then each keep silence, praying God to spare

His anger, cast not England quite away

In this her visitation!

A Puritan. Seven years long

The Midianite drove Israel into dens

And caves. Till God sent forth a mighty man,

Pym enters

Even Gideon!

Pym. Wentworth's come: nor sickness, care,

The ravaged body nor the ruined soul,

More than the winds and waves that beat his ship,

Could keep him from the King. He has not reached

Whitehall: they've hurried up a Council there

To lose no time and find him work enough.

Where's Loudon? your Scots' Parliament....

Loudon. Holds firm:

105

We were about to read reports.

Pym. The King

Has just dissolved your Parliament.

Loudon and other Scots. Great God!

An oath-breaker! Stand by us, England, then!

Pym. The King's too sanguine; doubtless Wentworth's here;

But still some little form might be kept up.

Hampden. Now speak, Vane! Rudyard, you had much to say!

Hollis. The rumor's false, then....

Pym. Ay, the Court gives out

His own concerns have brought him back: I know

'Tis the King calls him. Wentworth supersedes

The tribe of Cottingtons and Hamiltons

Whose part is played; there's talk enough, by this,—