The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Voyages of the Ranger and Crusader, by

W.H.G. Kingston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Voyages of the Ranger and Crusader

And what befell their Passengers and Crews.

Author: W.H.G. Kingston

Release Date: February 22, 2008 [EBook #24666]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE VOYAGES OF THE RANGER ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

W.H.G. Kingston

"The Voyages of the Ranger and Crusader"

Chapter One.

The Family Party.

“Harry, my boy; another slice of beef?” said Major Shafto, addressing his fine young sailor-son, a passed midshipman, lately come home from sea.

“No, thank you, since I could not, if I took it, pay due respect to the mince-pies and plum-pudding; but Willy here can manage another slice, I daresay. He has a notion, that he will have to feed for the future on ‘salt junk’ and ‘hard tack.’”

Willy Dicey was going to sea, and had just been appointed to Harry Shafto’s ship, the “Ranger.”

Among the large party of family friends collected at Major Shafto’s house on that Christmas Day not many years ago, was Lieutenant Dicey, a friend and neighbour of the Major’s, who had served with him in the same regiment for many years. The Lieutenant had lost a leg, and, unable to purchase his company, had retired from the army. His eldest son, Charles, and two of his daughters, Emily and May, had arranged to go out and settle in New Zealand; and they expected shortly to sail. The Lieutenant would gladly have gone with them, but he had a delicate wife and several other children, and thought it wiser, therefore, to remain at home. The party was a happy and cheerful one. The fire burned brightly, showing that there was a hard frost outside. The lamp shed a brilliant light over the well-covered table, and the Major did his best to entertain his guests. The first course was removed, and then came a wonderful plum-pudding, and such dishes of mince-pies! And then the brandy was brought and poured over them, and set on fire; and Harry Shafto and Willy Dicey tried if they could not eat them while still blazing, and, of course, burned their mouths, eliciting shouts of laughter; and the whole party soon thought no more of the future, and were happy in the present. How Mrs Clagget’s tongue did wag! She was a tall, old lady, going out to a nephew in New Zealand; and, as she was to be the companion of the young Diceys on the voyage, she had been asked to join the Christmas party.

Dinner was just over when voices were heard in the hall singing a Christmas carol, and all the guests went out to listen to the words which told of the glorious event which had, upwards of eighteen hundred years before, occurred in the distant East, and yet was of as much importance to all the human race, and will be to the end of time, as then. Ringers came next, and lastly mummers played their parts, according to an ancient custom, which some might consider “more honoured in the breach than in the observance.” After this there was blind-man’s buff, in which all the maid-servants as well as the children joined, and Mrs Clagget’s own maid and the Diceys’ Susan, who had come with the children. Well was that Christmas Day remembered by most of the party.

Soon after this the Diceys began to make active preparations for their intended voyage. Charles went up to London and engaged a passage for himself and sisters, and for Mrs Clagget, on board the “Crusader.” He came back, describing her as a very fine vessel, and he seemed well pleased with her commander, Captain Westerway.

As the time for parting approached, the young people began to feel that it would prove a greater trial than they had expected. While talking of their future life in the colony, and anticipating the various novel scenes and the new existence they were to enjoy, they had scarcely considered the wrench to their feelings which they would have to endure. Mr and Mrs Dicey had felt this, probably, from the first; and therefore, when the trial came, they were better prepared for it. Willy was the first to be got ready to start with his friend, Harry Shafto. We will, therefore, follow their fortunes before we accompany our other friends on their voyage.

Chapter Two.

The “Ranger” sails.

Harry and Willy leave home—Journey to Portsmouth—The “Blue Posts”—Midshipmen’s tricks—On board the “Ranger”—The soldier-officers—The sergeant’s wife—Mrs Morley and her family—Mrs Rumbelow nurses Willy—Cape of Good Hope—Sent to land troops—The “Ranger” in danger—Driving towards shore—The last anchor holds—Sail made—Mrs Rumbelow’s sermon—Troops carried on.

One bright morning at the end of January, the Portsmouth coach drove up to Major Shafto’s door. The Diceys were breakfasting at the house, for Harry Shafto’s leave was up, and he was to take Willy with him on board the “Ranger,” then lying in Portsmouth harbour. Farewells were said, fond embraces exchanged, for Harry, though a tall young man, was not ashamed to kiss his mother again and again, and his dear young sisters; nor did Willy mind the tears which trickled unbidden from his eyes. His heart was very full; though he had so longed to go to sea, now that he was actually going, he felt that he should be ready, if required, to give up all his bright hopes, and stay at home.

In spite of the cold, the whole family came out and stood at the door while the two young sailors mounted to the top of the coach. “All right,” shouted the guard, as the last article of luggage was handed up. The coachman gave a gentle lash to his horses, and the lads, standing up, turned round to give a last fond look at all those they loved so well.

This, it must be understood, was some time before Charles Dicey and his sisters started on their more important expedition. The young sailors expected to be home again in little more than a year, or perhaps even in less time, for the “Ranger” was a Government troop-ship, with the usual officers and crew, however, of a sloop-of-war. Harry Shafto would have preferred being in a dashing frigate, but, at the same time, he was glad to serve under so worthy a captain as Commander Newcombe.

Harry and his young companion, on their arrival at Portsmouth, went to the “Blue Posts,”—not an aristocratic hotel, certainly, but one resorted to in those days by the junior officers of the service. Willy felt very proud of his new uniform, and could not help handling his dirk as he sat by Harry Shafto’s side in the coffee-room. Several midshipmen and masters’ assistants came in. Two or three who took their seats at the same table asked Willy to what ship he belonged. “To the ‘Ranger’,” he answered proudly; “and a very fine ship she is.”

“Oh, ay, a lobster carrier,” observed a young midshipman, in a squeaky voice. “I have heard of old Newcombe. He is the savage fellow who tars and feathers his midshipmen if they get the ship in irons, or cannot box the compass when he tells them to do it.”

“I have been told, on the contrary, that he is a very kind man,” answered Willy; “and as to getting the ship in irons or boxing the compass, I do not think he would allow either the one thing or the other.”

“What! do you mean to call my word in question, youngster?” exclaimed the midshipman. “Do you know who I am?”

“Tell him you think he has eaten a good deal of the stuff they feed geese on,” whispered Harry.

Willy did as he was advised. The midshipman on this got very angry, especially when all his companions laughed at him, and advised him to let the “young chip” alone, as there was evidently an “old block” at his elbow, who was not likely to stand nonsense. At last the midshipman, who said that his name was Peter Patch, acknowledged that he himself had just been appointed to the “Ranger,” and that he believed old Newcombe to be a very good sort of a fellow, considering what officers generally are.

Next morning, after breakfast, Harry and his young companion went on board their ship, and Harry reported himself and Willy to the first-lieutenant, Mr Tobin. Captain Newcombe was on board; and when Harry, accompanied by Willy, went up and spoke to him on the quarterdeck, he received them very kindly.

Willy, by Harry’s advice, set to work at once to learn his duty. Peter Patch, though fond of practical jokes, was very good-natured, and assisted him as far as he could, telling him the names of the ropes, and showing him how to knot and splice, and the principle of sailing and steering a ship. Willy, who was a sharp little fellow, quickly took in all the instruction given him.

The midshipmen’s berth was somewhat confined, as, indeed, were those of the other officers, as a large portion of the space below was given up for the use of the troops. The poop cabins were devoted to the accommodation of the military officers and their families. There was also a space occupied by the hospital, and another portion by the women who accompanied the regiment, certain non-commissioned officers and privates being allowed to have their wives and children with them.

At length the ship was ready, and the soldiers were seen approaching her from Gosport. As they came up the side, they formed on deck, and each man had his allotted berth shown him; so that, although there were two hundred men, with a proportionate number of non-commissioned officers and their wives and families, there was perfect order and regularity observed. The “Ranger” had the honour of conveying Colonel Morley, who commanded the regiment, and there was a Mrs and two Miss Morleys. Then there was Captain Power, Captain Gosling, and Captain Twopenny; and Lieutenants Dawson, Hickman, and Ward; with Ensigns Holt and Gonne. There was a surgeon, David Davis, who hailed from Wales; and a paymaster, who was the stoutest man on board. There were several sergeants, but only one, Serjeant Rumbelow, whose name it is necessary to record. He was accompanied by his wife, who was a person well capable of keeping order, not only among the soldiers’ wives, but among the soldiers themselves. She was a woman of powerful frame and voice, tall and gaunt, and of a dauntless spirit. The regiment had not been on board many hours before Willy saw her go up to two young soldiers who were quarrelling. Seizing them, she knocked their heads together. “There, lads,” she exclaimed; “make it up this moment, or the next time I catch you at that work I’ll knock them a precious deal harder.”

Willy Dicey looked with a good deal of awe at Mrs Morley and her daughters, who appeared to be very great people. They quickly made themselves at home in their cabins, and had their work-boxes out, and a number of things arranged, as if they had been living there for weeks. Captain Newcombe made some remark on the subject. Mrs Morley replied, laughing, “You need not be surprised, for this will be the tenth voyage I have made, and you may suppose, therefore, that I am pretty well accustomed to roughing it. This ship is like a royal yacht compared to some vessels I have sailed in. My husband was not always a colonel, and subalterns and their wives have to put up with rough quarters sometimes.”

Harry Shafto was glad to find that most of the officers were gentlemanly men, and there appeared every prospect of their having a pleasant voyage.

As soon as the troops were on board, the ship went out to Spithead, and having taken in her powder and a few more stores, with a fair wind she stood down Channel.

The “Ranger” had to undergo not a little tumbling about in the Bay of Biscay, no unusual occurrence in that part of the ocean: it contributed to shake people and things into their places; and by the time she got into the latitude of Madeira, both military and naval officers, and the ladies on board, were pretty well acquainted. Colonel Morley found out that he had served with Major Shafto, and was very happy to make the acquaintance of his son; and Mrs Twopenny, for Captain Twopenny was married, was acquainted with the Diceys, and took Willy Dicey under her especial patronage. Mrs Rumbelow found out, somehow or other, that she had been nurse in his mother’s family, and, of course, Willy became a great pet of hers. Willy fell ill, and Mrs Rumbelow begged that she might nurse him, a favour very readily granted: indeed, had it not been for her watchful care, the doctor declared that little Dicey would have slipped through his fingers.

We need not accompany the “Ranger” in her course. With mostly favourable winds, she had a quick run to the Cape of Good Hope, and, without any accident, came to an anchor off Cape Town. Those who had not been there before looked with interest on the novel scene which presented itself from the anchorage. Willy Dicey, soon after his arrival, wrote a long letter home, from which one extract must be given:—

“Before us rose the perpendicular sides of Table Mountain, while on either hand we saw the crags of the Lion’s Head and Devil’s Peak, the former overhung by a large cloud, known as the Table-cloth. As it reached the edge, it seemed to fall down for a short distance, and then to disperse, melting away in the clear air. The town still preserves the characteristics given to it by its founders, many of the houses retaining a Dutch look, a considerable number of the inhabitants, indeed, having also the appearance of veritable Hollanders. The town is laid out regularly, most of the streets crossing each other at right angles, with rows of oak, poplar, and pine-trees lining the sides of the principal ones. Many of the houses have vine and rose-trees trailed over them; while the shutters and doors, and the woodwork generally, are painted of various colours, which give them a somewhat quaint but neat and picturesque appearance.”

Harry twice got a run on shore, but his duties confined him on board for the rest of the time the ship remained. She was on the point of sailing when news was received of a serious outbreak of the Kaffirs. A small body of troops on the frontier had been almost overwhelmed, and compelled to entrench themselves till relief could be sent to them. The Commander-in-chief accordingly ordered the “Ranger” to proceed immediately to the nearest point where it was supposed troops could be disembarked. It is known as Waterloo Bay. She arrived off the bay in the evening; but Captain Newcombe, not deeming it prudent to run into an unknown place during the night, stood away from the land, intending to return at daylight. In a short time, however, it fell calm. The lead was hove. It was evident that a current and swell combined were drifting the ship fast towards the shore, on which the surf was breaking heavily. On this the captain ordered an anchor to be let go, which happily brought her up. Though there was scarcely a breath of air, every now and then heavy rollers came slowly in, lifting the ship gently, and then, passing on, broke with a terrific roar on the rocky coast. The passengers were on deck. The young military officers chatted and laughed as usual, and endeavoured to make themselves agreeable to the ladies. Colonel Morley, however, looked grave. He clearly understood the dangerous position in which they were placed. Willy Dicey asked Harry what he thought about the matter.

“We must do our duty, and pray that the anchor may hold,” answered Harry.

“But if that gives way?” said Willy.

“We must let go another, and then another.”

“But if they fail us, and no breeze springs up?” said Willy.

“Then you and I must not expect to be admirals,” answered Harry.

“What do you mean?” asked the young midshipman.

“That a short time will show whether any one on board this ship is likely to be alive to-morrow,” said Shafto.

“You don’t mean to say that, Harry?” remarked Willy, feeling that the time had come when he must summon up all the courage he possessed, and of the amount he had as yet no experience. “You don’t seem afraid.”

“There’s a great deal of difference between knowing a danger and fearing to face it,” said Harry. “Not a seaman on board does not know it as well as I do, though they do not show what they think. Look at the captain—he is as cool and collected as if we were at anchor in a snug harbour; yet he is fully aware of the power of these rollers, and the nature of the ground which holds the anchor. There is the order to range another cable.”

Harry and Willy parted to attend to their respective duties. Night came on, but neither Commander Newcombe nor any of his officers went below. They were anxiously looking out for a breeze which might enable the ship to stand off from the dangerous coast. The night was passing by, and still the anchor held; at length, in the morning watch, some time before daylight, a breeze sprang up from the eastward, and the order was given to get under weigh. As the men went stamping round the capstan, a loud crash was heard.

“The messenger has given way, sir,” cried Mr Tobin, the first-lieutenant. Out ran the cable to the clench, carrying away the stoppers, and passing through both compressors. At length the messenger was again shackled, and the anchor hove up, when it was found that both flukes had been carried away.

Not, however, for some hours did the ship succeed in reaching Waterloo Bay, where she brought up, about a mile and a-half from the landing-place. A signal was made:—“Can troops land?” which was answered from the shore, “Not until the weather moderates,” the wind having by this time increased to a stiff breeze. A spring was now got on the cable, in case of its being necessary to slip; for it was very evident, if so heavy a surf set on shore in comparatively fine weather, that, should it come on to blow from the southward, the position of the ship would be still more critical.

As the day drew on, the breeze freshened, but the rollers at the same time increased, and broke heavily half-a-cable’s length to the westward of the ship, foaming and roaring as they met the resistance of the rockbound shore. The position of the “Ranger” was more dangerous than ever. The crew were at their stations; the soldiers were on deck, divided into parties under their officers, ready to assist in any work they might be directed to perform. Topgallant masts and royal masts were got up, and everything was prepared for making sail. The order was now given for shortening in the cable. As it was got on board, it was found that it had swept over a sharp rock about fifty fathoms from the anchor, and it seemed a miracle that it had not been cut through.

“Avast heaving,” cried the captain. “Loose sails.” In an instant the crew were aloft.

At that moment, as the topsails were filling, the second-lieutenant cried out from forward, “The cable has parted.”

“Let go the second bower,” cried the captain. The ship was drifting towards the rocks. Willy held his breath. What Harry had said might soon be realised. Mrs Morley and her daughters were on deck. They stood together watching the shore. Their cheeks were paler than usual, but they showed no sign of alarm, talking calmly and earnestly together. As Willy Dicey observed them, he wondered whether they could be aware of the danger they were in. To be sure, they might be lowered into the boat before the ship struck, but then the Colonel was not likely to quit his men, and they could not be indifferent to his safety. Still the ship drifted.

“Let go the sheet-anchor,” was the next order. All were looking out anxiously to ascertain whether she was driving nearer the treacherous surf. Many a breast drew a relieved breath. The last anchor had brought her up. Sails were now furled and royal yards sent down.

Near the “Ranger” an English barque was at anchor. Her master came on board, and volunteered to assist in making a hawser fast to his vessel, for the purpose of casting the ship the right way. “You will find, Captain Newcombe, that the rollers will soon be increasing, and, knowing the place as I do, I have great doubts whether the anchors will hold,” he observed; “I wish you were well out of this.” As he spoke, he cast an anxious glance astern, where the surf was breaking with terrific violence. The offer was gladly accepted. The two cutters were accordingly lowered to take hawsers to the barque. On the sheet-anchor being weighed, it came up without resistance. Both flukes had been carried away. The only hope of safety depended on the remaining anchor and cable holding till sail could be made. In vain the boats attempted to carry the hawsers to the barque. A strong current sent them to leeward, and they were accordingly ordered again on board. Happily, at this moment the wind veered a point to the east. There is no necessity to tell the men to be sharp. The order to make sail is given. The crew swarm aloft; the soldiers, under proper guidance, are stationed at the halliards, and the tacks and sheets. The cable is slipped, single-reefed topsails, courses, topgallant sails, jibs, and driver set. Few among even the brave seamen who do not hold their breath and offer up a silent prayer that the ship may cast the right way. Hurra! round she comes. The sails fill. She moves through the water. The boats with the hawser get alongside and are hoisted up, and the old “Ranger” stands out towards the open sea. Is there a soul on board so dull and ungrateful as not to return fervent thanks to a gracious superintending God for deliverance from the imminent danger in which they have been placed?

As the ship drew off the land, the rollers were seen coming in with increased strength and size, and it was very evident that, had she not got under weigh at the time she did, she would have been dashed to pieces in the course, probably, of another short hour, and few of the soldiers and crew would have escaped. (Note 1.)

“I tell you what, boys,” said Mrs Rumbelow, “you will have to go through a good many dangers in the course of your lives may be, but never will you have a narrower escape than this. I was just now thinking where we all should be to-morrow, and wishing I could be certain that we should all meet together in heaven. Not that I think any one of us have a right to go there for any good we have ever done; only I wish you boys to recollect, when you are rapping out oaths and talking as you should not talk, that at any moment you may be called away out of this world; and just let me ask you if you think that you are fit to enter the only place a wise person would wish to live in for ever and ever?”

Mrs Rumbelow was not very lucid, it may be, in her theology, but she was very earnest, and the regiment benefited more than some might be ready to allow by her sayings and doings too. Things might have been much worse had it not been for her.

It being found impossible to land the troops, the “Ranger” returned to Simon’s Bay, where she was detained some time longer in replacing the anchors and cables she had lost. Captain Newcombe was exonerated for not carrying out his directions, seeing it was impossible to do so. A little army of regulars and volunteers was despatched from another station for the relief of the hard-pressed garrison, and arrived just as their last cartridge and last biscuit had been expended. Other troops also coming out from England, the “Ranger” proceeded towards her previous destination.

Note 1. In 1846 H.M.S. “Apollo” was placed under exactly the circumstances described. It was in this locality, also, that the “Birkenhead” troop-ship was lost.

Chapter Three.

The “Crusader” leaves for New Zealand.

The young emigrants—Going on board emigrant ship—The “Crusader” described—Voyage to Plymouth—The cabin passengers—A mysterious passenger—Last sight of England—Mr Paget’s good example—Employment for emigrants—Visit from Neptune—Mawson in the Triton’s hands.

Charles Dicey and his sisters were busily employed from morning till night, after Willy left home, in preparing for their intended voyage, and for their future life in New Zealand. Charles was a very fair carpenter. He had also learned how to shoe a horse and to milk a cow. The latter accomplishment his sisters also possessed. They also knew how to make butter, and to bake bread, and pies, and tarts. They could manufacture all sorts of preserves, and could cook in a variety of ways; while, since they were young girls, they had made all their own dresses; indeed, they possessed numerous valuable qualifications for their intended life in a colony. Charles was a fair judge of horse-flesh, and not a bad one of cattle and sheep. He also possessed steadiness and perseverance, and those who knew him best foretold that he would make a successful settler.

The time fixed for the sailing of the “Crusader” was drawing on. The “Ranger,” it must be remembered, had sailed a short time before. This fact should not be forgotten.

The day before the emigrant ship was to sail, the old Lieutenant accompanied his children up to London, and had the honour of escorting Mrs Clagget at the same time. Though the “Crusader” was to touch at Plymouth, they wisely went on board at the port from which she first sailed, that they might have time to get their cabins in order, and the luggage carefully stowed away.

“Bless you, my children,” said Lieutenant Dicey, as he kissed his young daughters, and held Charles’ hand, gazing earnestly into his countenance. “I entrust these dear girls to you, and I know that you will act a brother’s part, and protect them to the utmost. But there are dangers to be encountered, and we must pray to One in heaven, who has the power, if He sees fit, to guard you from them.”

The “Crusader” was a fine ship, of about a thousand tons, with a poop-deck, beneath which were the cabins for the first-class passengers. Below their cabins were those for the second-class passengers, while the between-decks was devoted to the use of the steerage passengers. Thus there were three ranks of people on board; indeed, including the officers and crow, the good ship presented a little world of itself. Old Captain Westerway was the sovereign—a mild despot, however; but if he was mild, his first mate, Mr William Windy, or Bill Windy, as he was generally called, was very much the contrary, and he took care to bring those who trespassed on the captain’s mildness very quickly under subjection. The “Crusader” was towed down the Thames, and when clear of the river, the Channel pilot, who was to take her to Plymouth, came on board. We shall know more of her passengers as she proceeds on her voyage.

She had a pleasant passage round to Plymouth, with just sufficient sea on for a few hours to shake people into their places, and to make them value the quiet of Plymouth harbour. The wise ones, after the tumbling about they had received, took the opportunity of securing all the loose articles in their cabins, so that they might be prepared for the next gale they were destined to encounter.

At Plymouth a good many steerage and a few more cabin passengers came on board the “Crusader.” Captain Westerway informed those who had come round from London that he expected to remain in that magnificent harbour three days at all events, and perhaps longer, before finally bidding farewell to Old England.

The Misses Dicey had a cabin to themselves, their brother had a small one near theirs, and Mrs Clagget had one on the opposite side of the saloon; but they could hear her tongue going from morning till night; and very often, at the latter period, addressing her next-door neighbour whenever she guessed that she was not asleep. There were two young men, Tom Loftus and Jack Ivyleaf by name, going out as settlers. With the former, who was gentlemanly and pleasing, Charles Dicey soon became intimate. A card, with the name of Mr Henry Paget, had been nailed to the door of one of the cabins hitherto unoccupied. “I wonder what he is like,” said Emily to her sister May. “His name sounds well, but of course that is no guide. Captain Westerway says an agent took his passage, and that he knows nothing about him.” At length a slightly-built gentleman, prepossessing in his appearance, if not handsome, came up the side, and presented a card with Mr Henry Paget on it. The steward immediately showed him into his cabin, where for a short time he was engaged in arranging several cases and other articles. He then going on deck, took a few solitary turns, apparently admiring the scenery. Returning below, he produced a book from his greatcoat pocket and began reading, proceedings duly remarked and commented on by his fellow-passengers. “Who can he be?”

“What is taking him out to New Zealand?” were questions asked over and over again, without eliciting any satisfactory reply.

In the second cabin there was a Mr and Mrs Bolton, very estimable people apparently, from the way they took care of their children. There was an oldish man, James Joel, and a young farmer, Luke Gravel. The last person who came on board told the mate, Bill Windy, as he stepped up the side, that his name was Job Mawson. He had paid his passage-money, and handed his ticket. Windy, who was a pretty good judge of character, eyed him narrowly. The waterman who had put him on board, as soon as the last article of his property was hoisted up, pulled off to the opposite side of the Sound from which the emigrants had come, and thus no information could be obtained from him. There was an unpleasant expression on the man’s countenance. His glance was furtive, and he always seemed to be expecting some one to touch him on the shoulder, and say, “You are wanted;” so Charles remarked to his sisters.

It would be impossible to describe all the people. There were three other young ladies in the first cabin, and the steerage passengers were generally respectable persons, whose object in emigrating was to find sufficient scope for their industry. Some were farm labourers and farming people, others mechanics, and a few shopkeepers, who had been unsuccessful in England, but who hoped to do better in the colony.

At length the captain with his papers, and the agent, came on board, all visitors took their departure, the anchor was hove up, and the “Crusader” with a fair wind sailed out of the Sound. The next day she took her departure from the Land’s End, the last point of Old England many of those on board were destined to see. Mr Mawson now quickly recovered his spirits, and began to give himself the airs of a fine gentleman. “Circumstances compel me to take a second-class cabin,” he observed to Mr Paget, to whom he at first devoted his especial attention; “but you may suppose that, to a person of my birth and education, such is greatly repugnant to my feelings. However, this is one of the trials of life, sir, we must submit to with a good grace. Circumstances are circumstances, Mr Paget, and I am sure my young friend, Mr Dicey (I think, sir, that is your name?) will agree with me,” he added, turning to Charles.

“We make our own circumstances, sir, however,” answered Mr Paget, “by wise and prudent, or by foolish conduct, or by honest or dishonest dealings with our fellow-men. The upright man is not degraded by loss of fortune, and I have no doubt many persons of education go out in second-class cabins on board emigrant ships.”

“Of course they do, sir, of course,” exclaimed Mr Mawson; but either the tone or the words of Mr Paget did not please him, for he immediately afterwards walked away to another part of the ship.

Mr Paget had not been long on board before he visited the between-decks, and spoke to the fathers and mothers of the families on board. “It would be a pity that your children should be idle during the voyage,” he said; “and as perhaps some of them may be unable to read or write, I shall be happy to give them instruction.” In a short time he had a school established on board, and in a day or two afterwards he collected a Bible-class for the elder people; and then every morning he went below, and read the Bible to them, and offered up a prayer, and explained to them what he read.

“I thought, from his cut, he was one of those missionary fellows,” observed Mr Mawson to Charles Dicey with a sneer.

“I am very glad we have got such a person on board,” answered Charles, firmly. “If he will let me, I shall be very thankful to help him.”

Mr Paget gladly accepted Charles Dicey’s assistance, and the Miss Diceys offered to teach the girls, and they also undertook a sewing-class for the young women, many of whom scarcely knew how to use their needles properly. And then Tom Loftus, who was very ingenious, set to work to give employment to the young men. He got them to cut out models of all sorts, and showed them how to make brushes and other useful articles. Then he induced some of the sailors to teach them to knot and splice, and, indeed, to do all sorts of things.

“I am much obliged to you, gentlemen,” said Captain Westerway. “The last time I took out emigrants, they were almost in a state of mutiny. They had nothing to do on board, and idleness breeds mischief; and idle enough they were. Now, all these people seem as happy and contented as possible, and as far as I can judge, they are much the same class as the others.”

There was a black fiddler on board, who went by the name of Jumbo; and while he played the sailors danced, greatly to the amusement of the passengers. Jack Ivyleaf, who was up to all sorts of fun, used to join them, and soon learned to dance the hornpipe as well as the best dancer on board.

“I wonder, Mr Ivyleaf, you can so demean yourself,” exclaimed Mrs Clagget, when he came on the poop after his performance. “You, a gentleman, going and dancing among the sailors, and exhibiting yourself to the steerage passengers!”

“Why, Mrs Clagget, that is the very thing I did it for,” answered Jack, laughing. “I went on purpose to amuse them. I cannot teach them, like our friends Dicey and Loftus, and so I do what I can. I rather contemplate giving them some recitations, and I am going to sing some songs; and I am not at all certain that I will not act a play for their amusement.”

“Oh, you are incorrigible!” exclaimed Mrs Clagget; not that she really minded what Jack proposed to do, but she must say something.

The fine weather continued. Jack recited and sang songs to the people one evening, and the next he appeared in costume as a conjurer, and performed a number of wonderful tricks; and the third day he got an interesting book, and read out to them a story in a voice that might be heard right across the deck, so that he had a large number of auditors. At length it struck him that he might have a young men’s class; and before the day was over all the young men on board had begged to belong to it, so that he not only had plenty of pupils, but he got them on at a rapid rate. Thus the “Crusader” sailed onwards. The weather was getting hotter and hotter, and Jack Ivyleaf and several of his pupils were found to be especially busily employed in the forepart of the ship, with the assistance of the boatswain and some of the men; but what they were about no one could discover. At length Captain Westerway announced that the “Crusader” had reached the line. The sails were set, but there was so little wind that they hung against the masts, every now and then slowly bulging out, soon again to hang down in a discontented mood. The carpenter’s chips could be seen floating alongside sometimes for half-an-hour together, and the pitch in the seams of the deck bubbled and hissed, and the passengers, as they walked about, found their shoes sticking to it. Suddenly a loud noise was heard ahead. “Ship ahoy! What ship is that?”

“The ‘Crusader,’ Captain Westerway,” answered the master.

“Ay, ay, Captain Westerway, you are an old friend of mine, and I am sure you will welcome me on board,” sang out some one, apparently from beneath the bows.

“Who are you?” asked the captain.

“Daddy Neptune, to be sure,” answered the voice. “Don’t you know that? Your ship is just over my parlour windows, and shutting out the light, so that my wife and children can scarcely see to eat their porridge.”

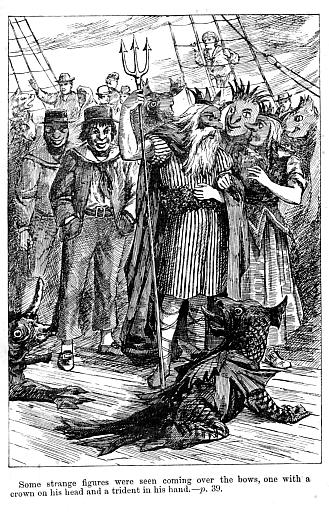

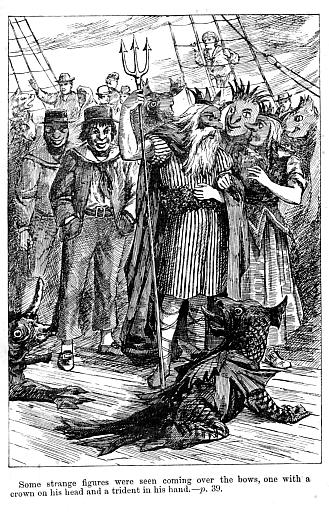

“I beg your pardon, but that is not my fault, as your Majesty well knows,” answered Captain  Westerway. “However, you are welcome on board.” As he spoke, some strange figures were seen coming over the bows, one with a crown on his head, a trident in his hand, and a huge nose and brownish beard, which flowed over his breast. He was evidently Daddy Neptune himself. His companions were in sea-green dresses, with conch shells in their hands, and among them were half-a-dozen strange-looking fish, who came walloping about the deck as if they supposed themselves still to be swimming in the water.

Westerway. “However, you are welcome on board.” As he spoke, some strange figures were seen coming over the bows, one with a crown on his head, a trident in his hand, and a huge nose and brownish beard, which flowed over his breast. He was evidently Daddy Neptune himself. His companions were in sea-green dresses, with conch shells in their hands, and among them were half-a-dozen strange-looking fish, who came walloping about the deck as if they supposed themselves still to be swimming in the water.

“Well, Captain Westerway, as you are an old friend, I will grant any favour you like to ask; so just out with it, and don’t stand on ceremony,” said Neptune, in a familiar, easy way.

The captain replied, “As my passengers here are leaving their native shore, and are about to settle in a strange country, I must beg that, after you have mustered all hands, your Majesty will allow them to pass without the ceremonies which those who cross the line for the first time have usually to go through.”

The passengers were accordingly called up on deck, when most of them, in acknowledgment of his courtesy, presented Daddy Neptune with a fee, which he forthwith handed to an odd-looking monster whom he took care to introduce as his treasurer. Mr Job Mawson, however, kept out of the way, evidently determined to pay nothing. Neptune, who had been eyeing him for some time, now turned to his attendants. Four of them immediately sprang forward, when Mr Mawson, suspecting their intentions, took to flight. Round and round the deck he ran, pursued by the tritons, to escape from whom he sprang below; but in his fright he went down forward, so that he could not reach his own cabin, and he was soon hunted up again and chased as before, till at length, exhausted, and nearly frightened out of his wits, he was caught beneath the poop.

“Let him alone,” exclaimed Neptune; “he is beneath our notice, after all.”

Instead of the rough amusements often carried on on board ships crossing the line, a drama was acted by Neptune and his attendants, he being shortly afterwards joined by his wife and children, who had by this time, he observed, finished their breakfasts, and had come to pay their respects to their old friend, Captain Westerway.

Chapter Four.

A Seaman’s Superstition.

“Ranger” takes a southerly course—Albatrosses appear astern—Holt prepares his rifle—Miss Morley pleads for the birds—Holt kills an albatross—A superstition of seamen—The fate of the Ancient Mariner—Mrs Rumbelow’s opinions on the subject—Serjeant Rumbelow—Music heard over the ocean—A ship passed at night—A hail from the “Ranger”—Blowing hard—Mrs Rumbelow comforts the sick—The colonel cautions the commander—Look-out for icebergs—The colonel’s wife and daughters—The colonel’s practical religion—A calm.

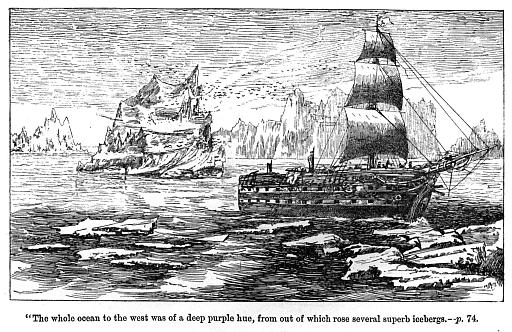

The lofty height of Table Mountain sank lower and lower in the blue ocean as the “Ranger” stood towards the south.

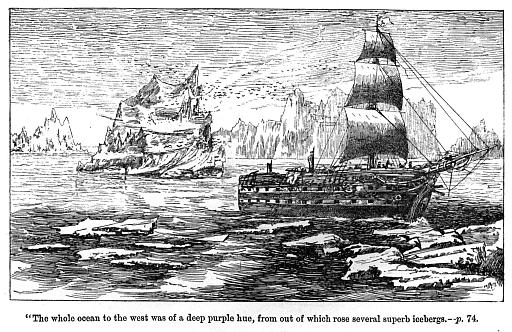

“I propose taking the short circle on our voyage eastward,” said Commander Newcombe to Colonel Morley. “We may experience somewhat cold weather; but, at this time of the year we may hope to escape heavy gales, and it is important, with so many men on board, to make a quick passage. If, too, our water should run scarce, we may obtain a supply from the icebergs, with which it is not impossible we may fall in now and then.”

“I hope we may not run foul of one,” observed Colonel Morley.

“No fear of that, colonel, if we have our eyelids open, and our wits about us,” answered the commander of the “Ranger.”

The sea was calm, the wind light, and the “Ranger” glided proudly over the smooth sea. The ladies and most of the other passengers were on deck. Two or three of the lieutenants and ensigns brought up their rifles and proposed shooting at the albatrosses, which, with expanded wings, floated around the ship, now rising high in the air, now darting down on the scrapings of the mess tins which had been thrown overboard. Ensign Holt had just loaded his rifle.

“I think I can hit that fellow,” he exclaimed, pointing at a magnificent bird which, at the instant, came swooping down near the stern.

“Oh! do not be so cruel,” exclaimed Miss Morley, who observed him. “I could not suppose that anybody with right feeling would wish to deprive so beautiful a creature of its joyous existence. How delightful it must be to fly at freedom through the clear blue air, and remain thus, for days and weeks together, away from the heat and dust of the shore.”

The ensign reddened, and lowered his weapon from his shoulder, and the albatross swept off to a distance, far out of range of his rifle.

“I was only thinking of the good practice they would give us,” he observed; “but your interference, Miss Morley, has saved the bird’s life.”

“That is to say, Holt, it prevented you from firing,” observed Lieutenant Dawson; “it does not follow that the bird would have been the sufferer.”

Lieutenant Hickman and Ensign Gonne laughed heartily, for Holt was not celebrated for his shooting. The magnificent birds continued as before, hovering about the ship, not aware of the evil intentions harboured against them by the young officers.

Ensign Holt was nettled, and, notwithstanding Miss Morley’s remark, was longing for an opportunity of exhibiting his skill. She soon afterwards went below, when he again prepared, as he said, to bring down an albatross. He and his brother officers, however, fired several shots without producing any effect. A rifle ball at length striking one of the birds, the white feathers were seen flying from its breast; upwards it soared, making several wide circuits, then once more darted towards the surface of the water, apparently not in any way the sufferer.

While the young officers were thus engaged, Commander Newcombe appeared on the poop. “I do not wish to interfere with the amusements of my passengers,” he observed; “but we sailors are apt to be superstitious, and we hold to the idea, if one of those magnificent birds is wantonly killed by any one on board a ship, she is sure to meet with some misfortune.”

“Why, captain, I do not see that there can be any more harm in killing an albatross than shooting a pheasant,” answered Ensign Holt, who was somewhat vexed at being thus a second time interfered with.

“The pheasant, sir, might serve for dinner,” observed the commander, “but I do not fancy you would wish to eat an albatross, even should you happen to shoot one, and we could lower a boat and pick it up. I confess I do not like to see the creatures wantonly injured. You may break a leg or wing of one of them, and leave it to suffer and die out in the ocean here; but your rifle balls can scarcely penetrate the bird’s thick coat of feathers, unless you get a fair shot at close range, so as to kill it outright.”

The young ensign, who did not at all like to be thus thwarted by the commander, had been watching a bird which, bolder than its companions, had more than once swooped close up to the taffrail. Determined to prove that he was not the bad shot it was supposed, he had kept his rifle capped and ready; he lifted it as the commander spoke, and fired. The albatross rose for an instant, and then, with expanded wings, fell heavily into the water, where it was seen struggling in a vain effort to rise.

“You have done for him, old fellow, at all events,” cried Lieutenant Dawson.

“Well, Holt, you have retrieved your character,” remarked the other ensign.

“I wish that Mr Holt would have listened to my advice,” said the commander, turning away annoyed. The young officers were too much engaged watching the poor bird to observe this. In another instant the struggles of the wounded albatross ceased, and immediately several of its companions pounced down upon it, and, ere the ship had run it out of sight, the body was almost torn in pieces.

“Why, it appears that your pets are somewhat ferocious creatures,” observed Lieutenant Dawson, pointing out what had occurred to Commander Newcombe, who had again returned aft.

“That is their nature, gentlemen,” he replied; “I have an idea, too, that it was implanted in them for a beneficent purpose. Better that the creature should be put out of its pain at once than linger on in agony. If we come to look into the matter, we shall find that every living creature is imbued with certain habits and propensities for a good purpose. I do not hold that anything happens by chance, or that the albatross is unworthy of being treated with humanity, because it acts in what you call a savage way. You will pardon me for being thus plain-spoken, gentlemen; and now Mr Holt has shown his skill by shooting one of those poor birds, I will ask you to favour me by not attempting to kill any more.”

Though not over well pleased at the interference of the commander, the young officers, feeling that his rebuke was just, discharged their rifles in the air, and did not again produce them during the voyage.

Willy Dicey and Peter Patch had been on the poop when these remarks had been made. “I say, Dicey, do you suppose that the commander really believes harm will come to the ship because Ensign Holt killed the albatross?” asked Peter, as they took a turn together on the port side of the quarterdeck.

“I should think not,” answered Willy. “I do not see what the one thing has to do with the other.”

“The sailors say, however, that it is very unlucky to kill an albatross,” observed Peter. “They fancy that the souls of people who die at sea fly about in the bodies of albatrosses, I suppose, or something of that sort—I am not quite certain; and for my part I wish that Ensign Holt had been less free with his rifle. I have always thought him a donkey, and donkeys do a good deal of mischief sometimes.”

“I will ask Harry Shafto what he thinks about it,” said Willy. “I have read a poem about a man who shot an albatross, and all the people died on board, and the ship went floating about till the masts and sails rotted, and he alone remained alive.”

“I suppose he lived on the ship’s stores then,” observed Peter. “He would have had plenty to eat, as there was no one to share the grub with him; but I should not like to have been in his skin. Did he ever get to shore, or how did people come to know it?”

“I think the old hulk reached the land after a good many years,” said Willy; “but I am not quite certain about that.”

“He must have had a terrible life of it, all alone by himself,” said Peter. “I should like to hear more of the story; but, I say, Dicey, are you certain that it is true?”

“No, I rather think it is a poet’s fancy, for the story is written in verse,” answered Willy.

“Well! that’s some comfort,” observed Peter; “because, you see, if the same thing was to happen to us, we should all have to die, and Ensign Holt would be the only person left on board the ‘Ranger.’”

Harry Shafto soon afterwards coming on deck, the two midshipmen appealed to him for his opinion. Harry laughed heartily.

“I think, however, that those soldier-officers might as well have let the poor birds alone,” he observed. “It is a cruel thing to shoot them, but I do not think any further harm will come of it.”

Still, neither Peter nor Willy were quite satisfied. “I’ll ask Mrs Rumbelow what she thinks about it,” said Willy. “She will soon get the opinion of the seamen, and I should not quite like to ask them myself.”

As soon as their watch was over, the two midshipmen went below, where they found Mrs Rumbelow seated on a chest, busily employed in darning her husband’s stockings, or in some other feminine occupation, as was her wont: Mrs Rumbelow’s fingers were never idle.

“Glad to see you, young gentlemen,” she said, looking up from her work. “Well, Mr Dicey, you don’t look like the same person you were before we reached the Cape; by the time you get home again they won’t know you.”

“If all goes well with us, perhaps not,” said Willy; “but Ensign Holt has gone and killed an albatross, and perhaps, as you know, that is a very dreadful thing to do. They say that evil is sure, in consequence, to come to the ship.”

Mrs Rumbelow looked at the faces of her two young visitors. “Do you think seriously that God rules the world in that fashion?” she asked, in a somewhat scornful tone. “Because a foolish young gentleman happens to kill a bird, will He who counts the hairs of our heads allow a number of His creatures, who have nothing to do with the matter, to suffer in consequence. Do not let such nonsense enter your heads, my dears.”

“We wanted you, Mrs Rumbelow, to inquire of the seamen what they think about the matter,” said Willy.

“I will do no such thing, and that’s my answer,” replied the sergeant’s wife; “harm may come to the ship, but it won’t be because of that, or anything of the sort.”

Just then Sergeant Rumbelow himself came up: in appearance he was very unlike his wife. Whereas she was tall and thin, he was comparatively short and broad; indeed, though of the regulation height, his width made him appear shorter than he really was; while his countenance, though burnt and tanned by southern suns and exposure to all sorts of weather, was fat and rubicund. He held his sides and laughed so heartily at the account his wife gave him of the questions which had been put to her, that Willy and Peter wished they had not mentioned the subject.

The wind was light and the ship made but little way for several days. Shafto, though only a mate, did duty as a lieutenant. Willy was in his watch; it was the middle watch. Willy enjoyed such opportunities of talking with his friend. The sea was perfectly smooth, there was only wind sufficient just to fill the sails, and the ship was making scarcely three knots through the water. Every now and then a splash was heard; some monster of the deep rose to the surface, and leaping forth, plunged back again into its native element. Strange sounds seemed to come from the far distance. A thick fog arose and shrouded the ship, so that nothing could be seen beyond the bowsprit.

“Keep a bright look-out there, forward,” sang out Shafto every now and then, in a clear ringing voice, which kept the watch forward on the alert.

“Hark!” said Willy; “I fancy I heard singing.”

“You heard the creaking yards against the masts, perhaps,” said Shafto.

“No, I am certain it is singing,” exclaimed Willy; “listen!”

Harry and his companion stopped in their walk; even Harry could not help confessing that he heard sweet sounds coming over the water. “Some emigrant ship, perhaps, bound out to Auckland,” he observed; “the passengers are enjoying themselves on deck, unwilling to retire to their close cabins. Sounds travel a long distance over the calm waters. She is on our beam, I suspect; but we must take care not to run into each other, in case she should be more on the bow than I suppose.” He hailed the forecastle to learn if the look-out could see anything. “Nothing in sight,” was the answer. “Keep a bright look-out, then,” he shouted. “Ay, ay, sir,” came from for’ard.

Soon after this the fog lifted. Far away on the starboard hand the dim outline of a tall ship appeared standing across their course. “She will pass under our stern if she keeps as she is now steering,” observed Harry; “the voices we heard must have come from her.”

The stranger approached, appearing like some vast phantom floating over the ocean, with her canvas spread on either hand to catch the light wind. “A sail on the starboard beam,” shouted the look-out, as he discovered her. It appeared as if she would pass within easy hail, when, just as Harry Shafto had told Willy to get a speaking-trumpet, she appeared to melt into a thin mist.

“What has become of her?” exclaimed Willy, feeling somewhat awe-struck.

“She has run into a bank of fog which we had not perceived,” said Shafto; “I will hail her;” and taking the speaking-trumpet, he shouted out, “What ship is that?” No answer came. Again he shouted, “This is Her Majesty’s ship ‘Ranger.’” All was silent. “Surely I cannot have been deceived,” he remarked; “my hail would have been answered if it had been heard.” Willy declared that he heard shouts and laughter, but Harry told him that was nonsense, and that undoubtedly the stranger was much further off than he had supposed her to be.

Before the watch was out, Harry had to turn the hands up to shorten sail; a strong breeze was blowing, increasing every instant in violence. Before morning the “Ranger” was ploughing her way through the ocean under close-reefed topsails, now rising to the summit of a sea, now plunged into the trough below. It was Willy’s first introduction to anything like a gale of wind.

“Well, Mr Dicey, you have at last got a sight of what the sea can be,” said Roger Bolland, the boatswain, with whom Willy was a favourite.

“I have got a feeling, too, of what it can do,” answered Willy, who was far from comfortable.

“Don’t you go and give in, though, like the soldiers below,” said the boatswain; “there are half of them on their backs already, and the gay young ensigns, who were boasting only the other day of what capital sailors they were, are as bad as the men.”

Though the whole battalion had been sick, Mrs Rumbelow was not going to knock under. She was as lively and active as ever, going about to the ladies’ cabins to assist them into their berths, and secure various articles which were left to tumble about at the mercy of the sea. If the truth must be known, she did not confine her attentions to them alone, but looked in as she passed on the young ensigns, offering consolation to one, handing another a little cold brandy and water, and doing her best to take comfort to all.

At length, after the ship had been tumbled about for nearly ten days, the gale began to abate, the soldiers recovered their legs, though looking somewhat pale and woebegone, and the cabin passengers once more appeared on deck. The weather, however, had by this time become very cold; there was no sitting down, as before, with work or book in hand, to while away the time; the ladies took to thick cloaks, and the military officers in their greatcoats walked the deck with rapid steps, as a matter of duty, for the sake of exercise. Gradually, too, the sea went down, and the “Ranger” glided forward on her course under her usual canvas.

Colonel Morley more than once asked the commander whether they had not by this time got into the latitude where icebergs were to be found. “We keep a sharp look-out for them, colonel, as I promised you,” answered the commander. “They are not objects we are likely to run upon while the weather remains clear, and as long as we have a good breeze there is no fear. They are, I confess, awkward customers to fall in with in a thick foe during a calm.”

“You may think I am over-anxious, captain,” observed the colonel, “but we cannot be too cautious with so many lives committed to our charge; and when I tell you that I was sole survivor of the whole wing of a regiment on board a ship lost by the over-confidence of her commander when I was an ensign, you will not be surprised at my mentioning the subject.”

“You are right, colonel, you are right,” said Commander Newcombe. “I pray that no such accident will happen to us; but danger must be run, though we who are knocking about at sea all our lives are apt to forget the fact till it comes upon us somewhat suddenly.”

Willy Dicey did not find keeping watch at night now quite so pleasant as in warmer latitudes; still, with his pea-coat buttoned well up to his chin, and his cap drawn tightly down over his head, he kept his post bravely on the forecastle, where he now had the honour of being stationed. “He is the most trustworthy midshipman on board,” said Mr Tobin, the first-lieutenant. “I can always depend on him for keeping his eyes open, whereas Peter Patch is apt to shut his, and make-believe he is wide awake all the time.” This praise greatly encouraged Willy. He determined to do his best and deserve it. Blow high or blow low, he was at his station, never minding the salt sprays which dashed into his eyes, and at times nearly froze there, when the wind blew cold and strong.

The “Ranger” continued her course, making good way, the wind being generally favourable.

The only grumblers among the passengers were three or four of the young lieutenants and ensigns, who, having finished all their novels, and not being addicted to reading works of a more useful description, found the time hang heavily on their hands. They ought to have followed the example of the Miss Morleys and their mother, who were never idle. Very little has hitherto been said about them. They were both very nice girls, without a particle of affectation or nonsense, though they had lived in barracks for some portion of their lives. Fanny, the eldest, was fair, with blue eyes, somewhat retroussé nose, and good figure, and if not decidedly pretty, the expression of her countenance was so pleasing that no one found fault with any of her features. Emma was dark, not quite so tall as her sister, but decidedly handsomer, with hazel eyes and beautifully formed nose and mouth. As yet, perhaps, they had had no opportunity of giving decided proof of any higher qualities they may have possessed, but they were both right-minded, religious girls. Some of the officers pronounced them far too strict, others considered them haughty, and one or two even ventured to pronounce them prudish, because they showed no taste for the frivolous amusements in which the ordinary run of young ladies indulge; not that they objected to dance, or to join in a pleasant pic-nic; indeed, the few who did find fault with them complained only of the way in which they did those things. Ensign Holt, who was not a favourite, whispered that he thought them very deep, and that time would show whether they were a bit better than other people. Neither Fanny nor Emma would have cared much for the opinion of Ensign Holt, even had they been aware of it. He might possibly have been prejudiced, from the fact that Mrs Morley, though very kind and motherly to all the young officers, had found it necessary to encourage him less than the rest. Ensign Holt, and indeed most of his brother officers, had no conception of the principles which guided the Misses Morley or their parents. They looked upon their colonel as not a bad old fellow, though rather slow; but somehow or other he managed to keep his regiment in very good order, and all the men loved him, and looked up to him as to a father. It was his custom to read the Bible every day in his cabin to his wife and daughters; and as there was no chaplain on board, he acted the part of one for the benefit of his men. His sermons were delivered in a fine clear voice, and were certainly not too long for the patience of his hearers; but Ensign Holt insisted that they were too strict: he did not like that sort of theology. Lieutenants Dawson and Hickman were inclined to echo Holt’s opinion. Whatever the captains thought, they had the good taste to keep it to themselves. Indeed, Power, the senior captain in the regiment, was suspected of having a leaning toward the colonel’s sentiments. No one, however, could say that he was slow or soft: he was known to have done several gallant acts, and was a first-rate officer, a keen sportsman, and proficient in all athletic exercises. It was whispered that Power was the only man likely to succeed with either the Miss Morleys, though, as far as was observed, he paid them no particular attention; indeed, he was not looked upon as a marrying man. He was the only unmarried captain on board. Captain Gosling had left his wife at home; and Mrs Twopenny was in delicate health, and generally kept her cabin. She has not before been mentioned. There were no other ladies on board, but there were several soldiers’ wives, with their children, though, altogether, there were fewer women than are generally found in a troop-ship.

A calm unusual for these latitudes had prevailed for several days. Now and then a light wind would come from the northward, just filling the sails, but again dying away; now the ship glided slowly over the smooth water; now she remained so stationary that the chips of wood swept overboard from the carpenter’s bench floated for hours together alongside.

Peter Patch asked Willy whether he did not think that the fate which befell the ship of the Ancient Mariner was likely to be theirs.

“I hope not,” said Willy; “particularly if the icebergs, which they say are not far off, should get round us, we should find it terribly cold.”

“But we should not die of thirst, as the crew of that unfortunate ship did,” observed Peter; “that’s one comfort.”

“Very cold comfort, though,” said Willy, who now and then ventured on a joke, if only Peter and some other youngster were within hearing.

Chapter Five.

“Iceberg ahead!”

A gale springs up—A dark night—Sound of breakers—Ship running on an iceberg—The “Ranger” scrapes along the berg—Providential escape—Ensign Holt’s alarm—The carpenter reports a leak—The chain-pumps rigged—the “Ranger” on her beam-ends—The masts cut away—Running before the gale—All hands at the pumps—The weather moderates—Prepare to rig jury-masts.

Once more a strong breeze had sprung up from the westward, and the ship was making good way through the water.

Though it was the summer time in the southern hemisphere, the weather was very variable; now, when the wind came from the antarctic pole, bitterly cold; or drawing round and blowing from the north, after it had passed over the warm waters of the Indian Ocean, it was soft and balmy.

It was Harry Shafto’s morning watch; he had just relieved the second-lieutenant. Willy was for’ard. It was blowing somewhat fresh, and the ship had a reef in her topsails and her courses set. The night was very dark. Willy having just been aroused from a midshipman’s sound sleep, was rubbing his eyes to get them clear. Now he peered out ahead into the darkness, now he rubbed them again, and shut and opened them, to satisfy himself that they were in good order. He could not distinguish who was on the forecastle, but he knew by the voice that one of the best men in the ship, Paul Lizard, was by his side.

“I have seen many a dark night, Mr Dicey, but this pretty well beats them all,” observed Paul. “It’s not one I should like to be caught in on a lee-shore or a strange coast; though out here, in the open sea, there is nothing to fear, as the highway is a pretty wide one, and we are not likely to fall in with any other craft crossing our course.”

“Very true,” answered Willy; “but there is one thing I have been told to do, and that is to keep a bright look-out, though it may be difficult enough to see an object; even should one be ahead.”

“On course, sir,” said Paul, “what is our duty must be done, though it would be a hard matter to see the ‘David Dunn’ of Dover, even if our jibboom were over her taffrail.”

“What ship is that?” asked Willy. “I never heard of her.”

“The biggest ship that ever was or ever will be, sir,” answered Paul, who was fond of a joke. “When she went about going up Channel once, her spanker pretty nigh swept away one of the towers of Calais, while her jibboom run right into Dover Castle.”

“She must have been a big ship, then,” said Willy.

The voice of the officer of the watch hailing the forecastle put a stop to Paul’s wit. “Ay, ay, sir,” he answered, in his usual stentorian voice; then he added, “It seems to be growing darker than ever.” So Willy thought, but still he tried his best with his sharp young eyes to penetrate the gloom.

“I wish it would clear,” observed Willy. “It is dark.”

“It couldn’t well be darker, sir,” said Paul; “to my mind it would be wise to shorten sail, or heave the ship to. The captain knows best, though.”

“It is getting very cold, though,” said Dicey. “I can feel the difference since the last five minutes.”

“I can’t say I feel it,” said Paul; “but hark, sir; I fancy I heard the sound of breakers.”

Willy listened, bending forward in his eagerness. “Yes,” he thought he heard a sound, and it seemed to be almost ahead, but yet it seemed to come from a long way off.

“It is only fancy after all,” observed Paul. The other men for’ard could hear nothing.

A few minutes passed. “What is that?” exclaimed Willy, with startling energy. “There seems to be a great white wall rising up before us.”

“Iceberg ahead!” shouted Paul, and he never hallooed louder in his life, “a little on the starboard bow.”

“Starboard the helm,” cried Harry from the quarterdeck. “Man the starboard braces. Brace the yards sharp up; call the captain; all hands on deck to save ship.” Such were the orders he issued in rapid succession. In an instant the boatswain’s whistle and the hoarse bawling of his mates was heard along the lower decks, and the ship, lately so silent and deserted, teemed with life. The crew came tumbling up from below, some with their clothes in their hands; the soldiers quickly followed, hurrying from their berths. Commander Newcombe and the other officers were on deck a few instants after the order to summon them had been given. He now took command, issuing his orders with the calmness of a man well inured to danger. Another voice was heard; it was that of Colonel Morley. “Soldiers, keep to your quarters,” he shouted out. The men, who had been rushing on deck, without a murmur obeyed the command.

The danger was indeed imminent. Sheer out of the ocean rose a huge white mountain, directly against which the ship appeared to be running headlong; but, answering her helm, she came up to the wind, though not in sufficient time altogether to avoid the danger. As Willy looked up, he expected to see the yards strike the sides of the iceberg, for such it was. A grating sound was heard: now it seemed as if the ship would be thrown bodily on to the icy mass; still she moved forward; now she heeled over to the wind, the yards again almost touching the frozen cliffs. An active leaper might have sprung on to the berg, could footing have been found. Every moment the crew expected to find their ship held fast by some jutting point, and speedily dashed to pieces; the bravest held their breath, and had there been light, the countenances of those who were wont to laugh at danger might have been seen blanched with terror.

Again and again the ship struck, as she scraped by the berg. It seemed wonderful, indeed, to those ignorant of the cause, that she should continue to move forward, and be driven ever and anon actually away from the ice. This was caused by the undertow, which prevented her from being thrown bodily on to the berg. Not a word was spoken, not an order issued, for all that could be done had been done. All were aware, however, that, even should she scrape clear of the berg, the blows her sides were receiving might at any moment rip them open, and send her helplessly to the bottom of the cold ocean.

The voyager on such an occasion may well exclaim, “Vain is the help of man!”

Harry, with the second-lieutenant, had gone for’ard among the men stationed on the forecastle, all eagerly looking out in the hopes of seeing the extreme end of the berg. Suddenly the white wall seemed to terminate, the ship glided freely forward, rising to the sea, which came rolling in from the north-west.

“Sound the well, Mr Chisel,” said the commander to the carpenter. All on deck stood anxiously waiting his report.

The berg appeared on the quarter, gradually becoming less and less distinct, till what seemed like a thin white mist alone was seen, which soon melted away altogether in the thick darkness. Still all well knew that other bergs might be in the neighbourhood, and a similar danger might have to be encountered.

The officers paced the deck, looking out anxiously, and those who, while the danger lasted, had not felt the cold, hurried below to finish dressing as best they could, or buttoned up their flushing coats, and wrapped comforters round their necks.

Colonel Morley returned to the cabin to tell his wife and daughters that the danger had passed. He found them pale and anxious, but neither trembling nor fainting. The two girls were seated on each side of their mother, holding her hands. They had been fully aware of the danger in which the ship had been placed, and they had together been offering up their prayers for their own safety and for that of all on board.

Peter Patch, finding himself near Willy, whispered that he should like to go and see how Ensign Holt had behaved himself. He would have found the ensign seated on the deck of his cabin with his bed-clothes pulled over his head, much too alarmed to think, or to utter any sounds but “Oh! oh! oh! what is going to happen? Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear, I wish I had not come!”

The other officers had collected in the main cabin, where Captain Power had taken his seat at the head of the table, giving encouragement to those around him, while their well-disciplined men, according to orders, kept to their quarters, the sergeants moving among them to see that no one went on deck. Mrs Rumbelow had taken the poor women under her charge, and did her best to comfort them.

“I told you so,” she exclaimed, when the ship was found to be moving easily forward, and those fearful grating sounds had ceased. “Just trust in God, and all will come right. Never cry out that all is lost while there is life, and even at the last moment hope that a way of deliverance may be found.”

The wind had increased, the courses had been taken off the ship, and she stood out under her topsails. It might have been supposed that nothing particular had occurred. All hands were at their stations, however, both watches being kept on deck; indeed, no one, even the most careless, felt inclined to go below.

The commander was walking the poop, awaiting the report of the carpenter; he had taken one or two turns, when a figure approached him.

“I don’t like the state of things,” said a voice which he recognised as that of Mr Chisel. “The ship is making water very rapidly; it’s coming in in several places, though the worst leaks are for’ard.”

“We must do our best to stop them, however,” answered the commander. “And, Mr Chisel, do not let more than necessary know this.” The first-lieutenant and master instantly hurried below to assist the carpenter in discovering the leaks. That they were high up seemed certain, and thus some hope existed that they might be reached. In time the chief injuries were discovered, and every effort was made to stop the leaks, old sails and blankets being used for the purpose. The pumps were immediately manned by the soldiers, who were told off to work them. Their clanking sound echoed along the decks, while, at the same time, the loud gush of the clear water rushing through the scuppers gave fearful proof of the large amount which must be rushing in. How eagerly all on board longed for daylight. The wind, however, was rising, and the ship heeled over on the side which had received the injury; she was accordingly put on the other tack, although it would take her out of her proper course.

All on board felt it to be a solemn time. The only sounds heard were those of the clanking pumps, and the gush of water as it was forced up from below. The wind was every instant increasing. The topsails were closely reefed, and the “Ranger” went plunging on into the fast-rising seas.

At length the cold light of early morn broke on the countenances of the crew; many looked pale and haggard. The past hours had been trying ones, and the soldiers, some in their shirts and trousers only, were labouring away manfully at the pumps; the crew at their stations, ready to obey the commands which any sudden emergency might demand. At length the carpenter reported that he had so far conquered the leaks that the ship might safely be put again on the port tack.

“Helm a-lee!” was heard. “Shift tacks and sheets! Mainsail haul! of all haul!” shouted Commander Newcombe; but at that instant, before the words were well out of his mouth, while the yards were in the act of being swung round, a terrific blast laid the ship over, a heavy sea striking her at the same time. For an instant it seemed as if she would never rise again. Shrieks were heart! rising from the foaming waters under her lee; several poor fellows were seen struggling amid them. No help could be given; no boat would have lived in that sea, had there been time to lower one, before they had sunk for ever. Their fate might soon be that of all on board.

The commander, after a moment’s consultation with the first-lieutenant and master, had summoned the carpenter, who appeared directly afterwards with his crew and several picked men with axes in their hands. They stood round the mizen-mast. “Cut,” he cried. The mizen shrouds were severed, a few splinters were seen to fly from the mast, and over it fell into the seething sea. Still the ship did not rise. They sprang to the mainmast. “That, too, must go,” said the commander, and issued the order to cut. In another instant the tall mast fell into the sea. For a moment it seemed doubtful whether that would have any effect. Suddenly the ship rose with a violent motion to an even keel, carrying away, as she did so, her fore-topmast. The helm was put up. Onwards she flew before the still-increasing gale. The seas rolled savagely up with foaming crests, as if trying to overwhelm her. To attempt to heave her to without any after-sail would now be hopeless.

Willy Dicey, who had gone aft, heard the commander remark to the first-lieutenant, that he hoped the gale would not last long, as otherwise they might be driven in among the ice, which would be found in heavy packs to the south-east. “With a moderate breeze we might reach New Zealand in ten days or a fortnight,” he observed. “I trust we can keep the old ship afloat till then.”

“Chisel thinks the injuries very severe, though,” said the first-lieutenant; “still, with the aid of the soldiers, we can keep the pumps going without difficulty, and we may be thankful that we have them on board.”

All day long the “Ranger” ran on, the wind and sea rather increasing than in any way lessening. Night once more approached, but no sign appeared of the gale abating. The soldiers relieved each other bravely at the pumps. Had it not been for them, the seamen well knew that the ship must have gone down; for though they might have worked them well, their strength must in time have given in. Mrs Rumbelow continued her kind ministrations to the women and children below; she had a word, too, for the seamen and soldiers, who were allowed half-a-watch at a time to take some rest. “You see, laddies,” she observed, “how you can all help each other. If the ship is to be kept afloat, and our lives saved, it will be by all working together with a will; you soldiers, by labouring at the pumps, and the sailors by taking care of the ship. If all do their duty there’s he fear, boys. I only wish people could learn the same in the everyday concerns of life—the world would get on much more happily than it does.”

While the sea continued rolling and the ship tumbling about, there were no hopes of getting up jury-masts. That night was even more trying than the previous one. It was not quite so dark, for now and then the clouds cleared away, and the bright stars shone forth; but still it was impossible to say whether some big iceberg might not be ahead, or whether the ship might not be driven into the midst of a field of ice, which would be scarcely less dangerous. All night long she ran on before the gale. It would be hopeless to attempt bringing her on a wind while the storm continued, and yet she was running into unknown dangers. Before, when she almost ran into the iceberg, she had had her masts standing, and was under easy steering canvas; now, with her after-masts gone, should an iceberg rise in her course, it would be scarcely possible for her to escape it.

Not a single officer of the ship, and but few of the men, went below that night. The military officers took their turn at the pumps to relieve their men; for, although so many were ready for the duty, so great was the exertion required, that they could continue at it but a few minutes together. As soon as one man was knocked up, another sprang into his place.

Another day dawned. It is easy to imagine how anxiously the night had been spent by all on board, especially by the poor ladies and soldiers’ wives. Happy were those who knew the power and effect of prayer. Wonderfully had they been supported. Those who knew not how to pray had been seated with hands clasped, or lying down with their heads covered up, endeavouring to shut out all thought of the future. Mrs Morley and her daughters had remained in their cabin, calm, though not unmoved, visited every now and then by the colonel; yet he could afford them but little consolation with regard to the safety of the ship. All he could say was that the men were doing their duty, and that they must hope for the best.

Ensign Holt had been missed by his brother officers, and roused up, not very gently, and had been compelled to take his turn at the pumps. He ought to have been very much obliged to them, as those are best off who are actively engaged in times of danger, though he grumbled considerably, declaring that it was not in the articles of war, and that he did not see why he should be made to work at the pumps like the common men.