The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Dingo Boys, by G. Manville Fenn

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Dingo Boys

The Squatters of Wallaby Range

Author: G. Manville Fenn

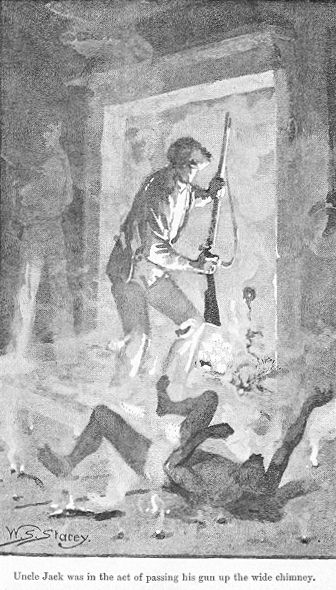

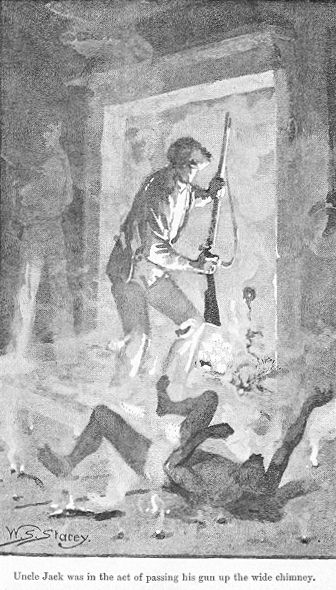

Illustrator: W. S. Stacey

Release Date: November 6, 2007 [EBook #23374]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DINGO BOYS ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

G Manville Fenn

"The Dingo Boys"

Chapter One.

“Have I Done Right?”

“Better stay here, squire. Aren’t the land good enough for you?”

“Oh yes; the land’s good enough, sir.”

“Stop and take up a run close by. If you go yonder, the piggers’ll eat you without salt.”

Here followed a roar of laughter from the party of idlers who were busy doing nothing with all their might, as they lounged about the wharves and warehouses of Port Haven.

Emigrants’ guide-books said that Port Haven was a busy rising town well inside the Barrier Reef on the east coast of Northern Australia, and offered abundant opportunities for intending settlers.

On this particular sunny morning Port Haven was certainly not “busy,” and if “rising,” it had not risen enough for much of it to be visible. There were a few wooden buildings of a very rough description; there was a warehouse or two; and an erection sporting a flagstaff and a ragged Union Jack, whose front edge looked as if the rats had been trying which tasted best, the red, white, or blue; and upon a rough board nailed over the door was painted in white letters, about as badly as possible, “Jennings’ Hotel;” but the painter had given so much space to “Jennings’,” that “Hotel” was rather squeezed, like the accommodation inside; and consequently from a distance, that is to say, from the deck of the ship Ann Eliza of London, Norman Bedford could only make out “Jennings’ Hot,” and he drew his brother and cousin’s attention to the fact—the ‘el’ being almost invisible.

“Well, who cares?” cried his brother Raphael.

“So’s everybody else,” said their cousin, Artemus Lake. “I’m melting, and feel as if I was standing in a puddle. But I say, Man, what a place to call a port!”

“Oh, it doesn’t matter,” said Norman. “Of course we’re not going to stop here. Are we going to anchor close up to that pier thing?”

“Pier, Master Norman?” said a hard-faced man in a glazed straw hat, “that’s the wharf.”

“Gammon! why, it’s only a few piles and planks.—I say, Rifle, look there. That’s a native;” and the boy pointed to a very glossy black, who had been squatting on his heels at the edge of the primitive wharf, but who now rose up, planted the sole of his right foot against the calf of his left leg, and kept himself perpendicular by means of what looked like a very thin clothes-prop.

“If that’s a native,” said Raphael, “he has come out of his shell, eh, Tim?”

“Yes,” said Artemus, solemnly. “Australian chief magnificently attired in a small piece of dirty cotton.”

Captain Bedford, retired officer of the Royal Engineers, a bluff, slightly grey man of fifty, who was answerable as father and godfather for the rather formidable names of the three bright, sun-burned, manly lads of fifteen to seventeen—names which the boys had shortened into “Man,” “Tim,” and “Rifle”—overheard the conversation and laughed.

“Yes, that’s a native, boys,” he said; “and it is a primitive place, and no mistake, but you’re right: we shall only stop here long enough to load up, and then off we go inland, pioneers of the new land.”

Man tossed up his straw hat, and cried “hooray!” his brother joined in, and the sailors forward, who were waiting to warp the great vessel alongside the rough wharf, joined in the cheer, supposing the shout to be given because, after months of bad weather, they were all safe in a sunny port.

At the cheer three ladies came out of the companionway, followed by a short, grey, fierce-looking man, who walked eagerly to the group of boys.

“Here, what’s the matter?” he cried. “Anything wrong?”

“No, uncle,” said Norman. “I only said ‘Hooray!’ because we have got here safe.”

“Did mamma and the girls come out because we cheered?” said Rifle. “Hallo, here’s Aunt Georgie too!”

He ran to the cabin entrance, from which now appeared an elderly lady of fifty-five or sixty, busily tying a white handkerchief over her cap, and this done as the boy reached her, she took out her spectacle-case.

“What’s the matter, Rifle?” she said excitedly. “Is the ship going down?”

“No, aunt, going up the river. We’re all safe in port.”

“Thank goodness,” said the lady, fervently. “Oh, what a voyage!”

She joined the ladies who had previously come on deck—a tall, grave-looking, refined woman of forty, and two handsome girls of about twenty, both very plainly dressed, but whose costume showed the many little touches of refinement peculiar to a lady.

“Well, Marian, I hope Edward is happy now.”

The lady smiled and laid her hand upon Aunt Georgina’s arm.

“Of course he is, dear, and so are we all. Safe in port after all those long weeks.”

“I don’t see much safety,” said Aunt Georgie, as she carefully arranged her spectacles, and looked about her. “Bless my heart! what a ramshackle place. Surely this isn’t Port Haven.”

“Yes; this is Port Haven, good folks,” said Captain Bedford, joining them and smiling at the wondering looks of all.

“Then the man who wrote that book, Edward, ought to be hanged.”

“What’s the matter, aunt?” said Norman, who hurried up with his cousin.

“Matter, my dear? Why, that man writing his rubbish and deluding your poor father into bringing us to this horrible, forsaken-looking place!”

“Forsaken?” cried Captain Bedford, “not at all. We’ve just come to it. Why, what more do you want? Bright sunshine, a glittering river, waving trees, a glorious atmosphere, and dear old Dame Nature smiling a welcome.—What do you say, Jack?”

The sharp, irritable-looking man had joined them, and his face looked perplexed, the more so as he noted that the girls were watching him, and evidently hanging upon his answer.

“Eh?” he cried; “yes; a welcome, of course. She’s glad to see our bonnie lassies fresh from Old England. Here, Ned, give me a cigar.”

“Thank you, Jack, old fellow,” whispered the captain, as he took out his case. “For Heaven’s sake help me to keep up the poor women’s spirits. I’m afraid it will be very rough for them at first.”

“Rough? Scarifying,” said Uncle John Munday, puffing away at his cigar. “No business to have come.”

“Jack! And you promised to help me and make the best of things.”

“Going to,” said Uncle Jack; “but I didn’t say I wouldn’t pitch into you for dragging us all away from—”

“Bloomsbury Square, my dears,” said Aunt Georgie just then. “Yes, if I had known, you would not have made me move from Bloomsbury Square.”

“Where you said you should die of asthma, you ungrateful old woman. This climate is glorious.”

“Humph!” said Aunt Georgie.

“Well, girls,” cried the captain, passing his arms round his daughter and niece’s waists, “what do you think of it?”

“Well, papa, I hardly know,” said Ida.

“This can’t be all of it, uncle?” said the other girl.

“Every bit of it, my pet, at present; but it will grow like a mushroom. Why, there’s an hotel already. We had better get ashore, Jack, and secure rooms.”

“No,” said Uncle Jack, decisively, as he watched a party of rough-looking idlers loafing out of the place, “we’ll arrange with the captain to let us stay on board till we go up-country. Rather a shabby lot here, Ned.”

“Um! yes,” said Captain Bedford, smiling at the appearance of some of the men as they gathered on the wharf.

“Better stay here, I say; the women will be more comfortable. As we are going up the country, the sooner we load up and get off the better. German and I and the boys will camp ashore so as to look after the tackle.”

“Yes, and I’ll come too.”

“No,” said Uncle Jack; “your place is with your wife and the girls.”

“Perhaps you are right,” said the captain, as he stood watching the sailors busily lowering a boat to help to moor the great, tall-masted ship now sitting like a duck on the smooth waters of the river, after months of a stormy voyage from England, when for days the passengers could hardly leave the deck. And as he watched the men, and his eyes wandered inland toward where he could see faint blue mountains beyond dark green forests, he asked himself whether he had done right in realising the wreck of his property left after he had been nearly ruined by the proceedings of a bankrupt company, and making up his mind at fifty to start afresh in the Antipodes, bringing his wife, daughter, and niece out to what must prove to be a very rough life.

“Have I done right?” he said softly; “have I done right?”

“Yes,” said a voice close to him; and his brother’s hand was laid upon his arm. “Yes, Ned, and we are going to make the best of it.”

“You think so, Jack?” said the captain, eagerly.

“Yes. I was dead against it at first.”

“You were.”

“Horribly. It meant giving up my club—our clubs, and at our time of life working like niggers, plunging into all kinds of discomforts and worries; but, please God, Ned, it’s right. It will be a healthy, natural life for us all, and the making of those three boys in this new land.”

Captain Bedford grasped his brother’s hand; but he could not speak. The comfort given by those words, though, was delightful and his face lit up directly with a happy smile, as he saw the excitement of the three boys, all eager to begin the new life.

He looked a little more serious though, as his eyes lit on the party of ladies fresh from a life of ease; but his countenance brightened again as he thought of how they would lighten the loads of those ill able to bear them. “And it will be a happy, natural life for us all. Free from care, and with only the troubles of labour in making the new home.”

But Captain Bedford was letting his imagination run. More troubles were ahead than his mind conceived, and directly after he began making plans for their start.

Chapter Two.

“We’re off now.”

Busy days succeeded during which every one worked hard, except the people of Port Haven. The captain of the ship hurried on his people as much as was possible, but the sailors obtained little assistance from the shore. They landed, however, the consignments of goods intended for the speculative merchant, who had started in business in what he called sundries; two great chests for the young doctor, who had begun life where he had no patients, and passed his time in fishing; and sundry huge packages intended for a gentleman who had taken up land just outside the town, as it was called, where he meant to start sugar-planting.

But the chief task of the crew was the getting up from the hold and landing of Captain Bedford’s goods; and these were so varied and extensive that the inhabitants came down to the wharf every day to look on as if it were an exhibition.

Certainly they had some excuse, for the captain had gone to work in rather a wholesale way, and the ship promised to be certainly a little lighter when she started on her way to her destination, a port a hundred miles farther along the coast.

For, setting aside chests and packing-cases sufficient to make quite a stack which was nightly covered with a great wagon cloth, there were a wagon and two carts of a light peculiar make, bought from a famous English manufacturer. Then there were tubs of various sizes, all heavily laden, bundles of tent and wagon cloths, bales of sacking and coarse canvas, and crates of agricultural machinery and tools, on all of which, where they could see them, the little crowd made comments, and at last began to make offers for different things, evidently imbued with the idea that they were brought out on speculation.

The refusals, oft repeated, to part with anything, excited at last no little resentment, one particularly shabby, dirty-looking man, who had been pointed out as a squatter—though that term ought certainly to have been applied to the black, who was the most regular and patient of the watchers—going so far as to say angrily that if stores were brought there they ought to be for sale.

These heavy goods were the last to be landed, for after making a bargain with the gentleman whose name appeared in such large letters on the front of his great wooden shanty, four horses, as many bullocks, all of colonial breed, bought at Sydney where the vessel touched, half a dozen pigs, as many sheep, and a couple of cows brought from England, were landed and driven into an ill-fenced enclosure which Mr Jennings called his “medder,” and regularly fed there, for the landlord’s meadow was marked by an almost entire absence of grass.

Day by day, these various necessaries for a gentleman farmer’s home up-country were landed and stacked on the wharf, the boys, Uncle John, and Samuel German—“Sourkrout,” Norman had christened him—under the advice of the captain seeing to everything, and toiling away in the hot sunshine from morning to night.

At last all the captain’s belongings were landed, and the next proceeding was to obtain half a dozen more bullocks for draught purposes, and two or three more horses.

These were found at last by means of the young doctor, who seemed ready to be very civil and attentive, but met with little encouragement. After the landlord had declared that neither horse nor ox could be obtained there, the doctor took Captain Bedford about a couple of miles up the river, and introduced him to the young sugar-planter, who eagerly supplied what was required, not for the sake of profit, but, as he said, to do a stranger a kindly turn.

“Going up the country, then, are you?” he said. “Hadn’t you better take up land where you can get help if you want it?”

“No,” said the captain, shortly. “I have made my plans.”

“Well, perhaps you are right, sir,” said the sugar-planter, who was, in spite of his rough colonial aspect and his wild-looking home, thoroughly gentlemanly. “You will have the pick of the land, and can select as good a piece as you like. I shall look you up some day.”

“Thank you,” said the captain, coldly; “but I daresay I shall be many miles up the river.”

“Oh, we think nothing of fifty or a hundred miles out here, sir,” said the young squatter, merrily. “Your boys will not either, when you’ve been up yonder a month. Come and see me, lads, when you like. One’s glad of a bit of company sometimes.”

They parted and walked back, driving their new acquisitions, and were getting on very badly, from the disposition on the part of the bullocks to return to their old home, when the black already described suddenly made his appearance from where he had been squatting amongst some low-growing bushes; and as soon as he stepped out into the track with his long stick, which was supposed to be a spear, bullocks and horses moved on at once in the right direction, and perhaps a little too fast.

“The cattle don’t like the blacks as a rule. They are afraid of the spears,” said the doctor.

“Why?” asked Norman.

“The blacks spear them—hurl spears at the poor brutes.”

“Black fellow,” said the shiny, unclothed native sharply, “spear um bullockum.”

“Why, he can speak English,” said Rifle, sharply.

“Oh yes, he has hung about here for a long time now, and picked it up wonderfully.—You can talk English, can’t you, Ashantee?”

The black showed his teeth to the gums.

“What’s his name?” asked Artemus, otherwise Tim.

“Oh, that’s only the name I gave him, because he is so black—Ashantee.”

“Eh, you want Shanter?” cried the black sharply.

“No; but mind and drive those bullocks and horses down to Jennings’, and the gentleman will give you sixpence.”

“You give Shanter tickpence?” he cried eagerly, as he lowered his rough shock-head and peered in the captain’s face.

“Yes, if you drive them carefully.”

“Hoo!” shouted the black, leaping from the ground, and then bursting out with a strange noise something between a rapid repetition of the word wallah and the gobbling of a turkey-cock; and then seeing that the boys laughed he repeated the performance, waved his clumsy spear over his head, and made a dash at the bullocks, prodding them in the ribs, administering a poke or two to the horses, and sending them off at a gallop toward the port.

“No, no, no, stop him!” cried the captain; and the three boys rushed off after the black, who stopped for them to overtake him.

“What a matter—what a matter?” he said coolly, as they caught and secured him.

“Mind he don’t come off black, Tim,” cried Norman.

“Black? All black,” cried the Australian. “White, all white. Not white many.”

“That’s not the way to drive cattle,” cried the young doctor, as he came up with the captain.

“Not give tickpence drive bullockum?”

“Yes, if you are careful. Go slowly.”

“Go slowly.”

“No. Bullockum ’top eat grass. Never get along.”

“You’ll make them too hot,” said Rifle.

“No, no,” shouted the black; “no can get too hot. No clothes.”

“Send the fellow about his business,” said the captain; “we’ll drive the cattle ourselves. Good lesson for you, boys.—Here you are, Shanter.”

He took out a bright little silver coin, and held it out to the black, who made a snatch at it, but suddenly altered his mind.

“No, not done drive bullockum. Wait bit.”

He started off after the cattle again, but evidently grasped what was meant, and moved steadily along with the three boys beside him, and he kept on turning his shiny, bearded, good-humoured face from one to the other, and displaying a perfect set of the whitest of teeth.

“Seems ruin, doesn’t it?” said Tim, after they had gone steadily on for some time in silence—a silence only broken by a bellow from one of the bullocks.

“Hear um ’peak?” cried the black.

“What, the bullock?” said Rifle.

The black nodded.

“Say don’t want to go along. Shanter make um go.”

“No, no, don’t hunt them.”

“No,” cried the black, volubly; “hunt wallaby—hunt ole man kangaroo.”

He grinned, and holding his hands before him, began to leap along the track in a wonderfully clever imitation of that singular animal last named, with the result that the horses snorted, and the bullocks set up their tails, and increased their pace.

“Be quiet!” cried Norman, whose eyes ran tears with laughter. “Yes, you are right, Tim. He is a rum one.”

“I meant it seems rum to be walking along here with a real black fellow, and only the other day at Harrow.”

“Black fellow?” cried their companion. “Hi! black fellow.”

He threw himself into an attitude that would have delighted a sculptor, holding back his head, raising his spear till it was horizontal, and then pretending to throw it; after which he handed it quickly to Norman, and snatched a short knobbed stick from where it was stuck through the back of the piece of kangaroo skin he wore.

With this in his hand he rushed forward, and went through the pantomime of a fierce fight with an enemy, whom he seemed to chase and then caught and killed by repeated blows with the nulla-nulla he held in his hand, finishing off by taking a run and hurling it at another retreating enemy, the club flying through the air with such accuracy that he hit one of the horses by the tail, sending it off at a gallop.

“Norman! Rifle!” cried the captain from far behind; “don’t let that fellow frighten those horses.”

“I—I—can’t help it, father,” cried the boy, who was roaring with laughter.

“Tink Shanter funny?” cried the black; and he gave vent to the wallah-wallah noise again.

“Yes, you’re a rum beggar,” said Rifle, who looked upon him as if he were a big black child.

“Yes; Shanter rum beggar,” said the black, with a satisfied smile, as if pleased with the new title; but he turned round fiercely directly after, having in his way grasped the meaning of the words but incorrectly.

“No, no,” he said eagerly; “Shanter no rum beggar. No drunkum rum. Bah! ugh! Bad, bad, bad!”

He went through an excited pantomime expressive of horror and disgust, and shook his head furiously. “Shanter no rum beggar.”

“I meant funny,” said Rifle.

“Eh? Funny? Yes, lot o’ fun.”

“You make me laugh,” continued Rifle.

“Eh? make um laugh? No make black fellow laugh. Break um head dreffle, dreffle. No like black fellow.”

In due time they were close up to the hotel, where, the boys having taken down the rails, the new purchases made no scruple about allowing themselves to be driven in to join the rest of the live-stock, after which Shanter went up to the captain.

“Get tickpence,” he cried, holding out his hand.

The coin was given, and thrust into the black’s cheek.

“Just like a monkey at the zoological,” said Norman, as he watched the black, who now went to the wharf, squatted down, and stared at the stern, sour-looking man—the captain’s old servant—who was keeping guard over the stack of chests, crates, and bales.

The next thing was the arranging for the loan of a wagon from the landlord, upon the understanding that it was to be sent back as soon as possible. After which the loading up commenced, the new arrivals performing all themselves, the inhabitants of the busy place watching, not the least interested spectator being the black, who seemed to be wondering why white men took so much trouble and made themselves so hot.

One wagon was already packed by dusk, and in the course of the next day the other and the carts were piled high, the captain, from his old sapper-and-miner experience, being full of clever expedients for moving and raising weights with rollers, levers, block and fall, very much to the gratification of the dirty-looking man, who smoked and gave it as his opinion that the squire was downright clever.

“Your father was quite right, boys,” said Uncle Jack, as the sheets were tightened over the last wagon. “We could not stop anywhere near such neighbours as these.”

Then came the time when all was declared ready. Seats had been contrived behind the wagons; saddles, ordinary and side, unpacked for the horses; the tent placed in the care which bore the provisions, everything, in short, thought of by the captain, who had had some little experience of expeditions in India when with an army; and at last one morning the horses were put to cart and wagon, one of which was drawn by three yoke of oxen; every one had his or her duty to perform in connection with the long caravan, and after farewells had been said to their late companions on board ship and to the young doctor and the sugar-planter, all stood waiting for the captain to give the word to start.

Just then the doctor came up with his friend of the plantation.

“You will not think me impertinent, Captain Bedford, if I say that Henley here advises that you should keep near to the river valley, just away from the wood, so as to get good level land for your wagons.”

“Certainly not; I am obliged,” said the captain quietly.

“He thinks, too, that you will find the best land in the river bottom.”

“Of course, of course,” said the captain. “Good-day, gentlemen; I am much obliged.”

“If you want any little service performed, pray send,” said the doctor; “we will execute any commission with pleasure.”

“I will ask you if I do,” said the captain; and the two young men raised their hats and drew back.

“Father doesn’t like men to be so civil,” said Man.

“No; he doesn’t like strangers,” whispered back Rifle.

“Of course he doesn’t,” said Tim, in the same low voice. “It wasn’t genuine friendliness.”

“What do you mean?” said Man.

“Why, they wouldn’t have been so full of wanting to do things for us if it had not been for the girls. They couldn’t keep their eyes off them.”

“Like their impudence,” said Rifle, indignantly.

“Of course. Never thought of that,” cried Man.

Just then the captain, a double-barrelled rifle in his hand, and well mounted, was giving a final look round, when the dirty-looking fellow lounged up with about a dozen more, and addressed him as duly set down at the beginning of the first chapter.

But the laughter was drowned by the sound of wheels and the trampling of hoofs; the wagons and carts moved off, each with a boy for driver, and Uncle Munday came last, mounted like his brother, to act the part of herdsman, an easy enough task, for the cattle and spare horses followed the wagons quietly enough after the fashion of gregarious beasts.

The little caravan had gone on like this for about a mile along a track which was growing fainter every hundred yards, when Man Bedford gave his whip a crack, and turned to look back toward the sea.

“We’re off now, and no mistake,” he said to himself. “What fun to see Uncle John driving cattle like that! why, we ought to have had Master Ashantee—Tam o’ Shanter—to do that job. I wonder whether we shall see any fellows up the country as black as he.”

His brother and cousin were musing in a similar way, and all ended by thinking that they were off on an adventure that ought to prove exciting, since it was right away west into an almost unknown land.

Chapter Three.

“Are You Afraid?”

After the first few miles the tracks formed by cattle belonging to the settlers at Port Haven disappeared, and the boys, though still full of excited anticipations, gazed with something like awe at the far-spreading park-like land which grew more beautiful at every step. To their left lay the winding trough-like hollow along which the river ran toward the sea; away to their right the land rose and rose till it formed hills, and beyond them mountains, while higher mountains rose far away in front toward which they made their way.

For the first hour or two the task of driving was irksome, but once well started the little caravan went on easily enough, for it soon became evident that if one of the laden carts was driven steadily on in front, the horses and bullocks would follow so exactly that they would almost tread in their leader’s feet-marks, and keep the wheels of cart and wain pretty well in the ruts made by those before. As to the cattle Uncle Munday drove, they all followed as a matter of course, till a pleasant glade was reached close by the river, where it was decided to stop for the mid-day halt. Here carts and wagons were drawn up in a row, the cattle taken out, and after making their way to a convenient drinking place, they settled down to graze on the rich grass with perfect content.

Meanwhile, to Norman’s great disgust, he and Artemus were planted at a distance in front and rear to act as sentries.

“But there isn’t anything to keep watch over,” said the elder boy in remonstrance.

“How do you know, sir?” cried the captain, sharply. “Recollect this—both of you—safety depends upon our keeping a good look-out. I do not think the blacks will molest us, but I have been a soldier, Man, and a soldier always behaves in peace as he would in war.”

“More blacks in London,” said Tim, as they moved off to take up their positions on a couple of eminences, each about a quarter of a mile away.

“Yes,” replied Man, who was somewhat mollified on finding that he was to keep guard with a loaded gun over his shoulder. “I say, though, doesn’t it seem queer that nobody lives out here, and that father can come and pick out quite a big estate, and then apply to the government and have it almost for nothing?”

“It does,” said Tim; “but I should have liked to stop in camp to have dinner.”

“Oh, they’ll send us something, and—look, look—what are those?”

A flock of great white cockatoos flew nearly over their heads, shrieking at them hoarsely, and went on toward the trees beyond the camp.

“I say, doesn’t it seem rum? They’re cockatoos.”

“Wild, and never saw a cage in their lives.”

“And we never fired and brought them down, and all the time with guns on our shoulders. Look!”

“Father’s waving to us to separate. I daresay they’ll send us something to eat.”

The boys separated and went off to their posts, while smoke began to rise in the little camp, the tin kettle was filled and suspended over the wood fire, and Aunt Georgie brought out of their baggage the canister of tea and bag of sugar set apart for the journey.

Bread they had brought with them, and a fair amount of butter, but a cask of flour was so packed that it could be got at when wanted for forming into damper, in the making of which the girls had taken lessons of a settler’s wife at the port.

In making his preparations Captain Bedford had, as hinted, been governed a good deal by old campaigning experience, and this he brought to bear on the journey.

“Many things may seem absurd,” he said, “and out of place to you women, such for instance as my planting sentries.”

“Well, yes,” said Aunt Georgie, “it’s like playing at soldiers. Let the boys come and have some lunch.”

“No,” said the captain; “it is not playing: we are invaders of a hostile country, and must be on our guard.”

“Good gracious!” cried Aunt Georgic, looking nervously round; “you don’t mean that we shall meet with enemies?”

“I hope not,” said the captain; “but we must be prepared in case we do.”

“Yes; nothing like being prepared,” said Uncle Munday. “Here, give me something to eat, and I’ll go on minding my beasts.”

“They will not stray,” said the captain, “so you may rest in peace.”

It was, all declared, a delightful alfresco meal under the shade of the great tree they had selected, and ten times preferable to one on board the ship, whose cabin had of late been unbearably hot and pervaded by an unpleasant odour of molten pitch.

To the girls it was like the beginning of a delightful picnic, for they had ridden so far on a couple of well-broken horses, their path had been soft grass, and on every side nature looked beautiful in the extreme.

Their faces shone with the pleasure they felt so far, but Mrs Bedford’s countenance looked sad, for she fully grasped now the step that had been taken in cutting themselves adrift from the settlers at the port. She had heard the bantering words of the man when they started, and they sent a chill through her as she pictured endless dangers, though at the same time she mentally agreed with her husband that solitude would be far preferable to living among such neighbours as the people at the port.

She tried to be cheerful under the circumstances, arguing that there were three able and brave men to defend her and her niece and daughter, while the boys were rapidly growing up; but, all the same, her face would show that she felt the risks of the bold step her husband was taking, and his precautions added to her feeling of in security and alarm.

In a very short time Rifle had finished his meal, and looked at their man German, who was seated a little way apart munching away at bread and cheese like a two-legged ruminant. He caught the boy’s eye, grunted, and rose at once.

“Shall we relieve guard, father?” said Rifle.

“No, but you may carry a jug of tea to the outposts,” was the reply; and after this had been well-sweetened by Aunt Georgie, the boy went off to his cousin Tim, not because he was the elder, but on account of his being a visitor in their family, though one of very old standing.

“Well,” he cried, as he approached Tim, who was gazing intently at a patch of low scrubby trees a short distance off; “seen the enemy?”

“Yes,” said the boy, in a low earnest whisper. “I was just going to give warning when I saw you comma.”

Rifle nearly dropped the jug, and his heart beat heavily.

“I say, you don’t mean it?” he whispered.

“Yes, I do. First of all I heard something rustle close by me, and I saw the grass move, and there was a snake.”

“How big?” cried Rifle, excitedly; “twenty feet?”

“No. Not eight, but it looked thick, and I watched it, meaning to shoot if it showed fight, but it went away as hard as ever it could go.”

“A snake—eight feet long!” cried Rifle, breathlessly. “I say, we are abroad now, Tim. Why didn’t you shoot it?”

“Didn’t try to do me any harm,” replied Tim, “and there was something else to look at.”

“Eh? What?”

“Don’t look at the wood, Rifle, or they may rush out and throw spears at us.”

“Who?—savages?” whispered Rifle.

“Yes; there are some of them hiding in that patch of trees.”

“Nonsense! there isn’t room.”

“But I saw something black quite plainly. Shall I fire?”

“No,” said Rifle, stoutly. “It would look so stupid if it was a false alarm. I was scared at first, but I believe now that it’s all fancy.”

“It isn’t,” said Tim in a tone full of conviction; “and it would be ever so much more stupid to be posted here as sentry and to let the enemy come on us without giving the alarm.”

“Rubbish! There is no enemy,” cried Rifle.

“Then why did my uncle post sentries?”

“Because he’s a soldier,” cried the other. “Here, have some tea. It isn’t too hot now, and old Man’s signalling for his dose.”

“I can’t drink tea now,” said Tim, huskily. “I’m sure there’s somebody there.”

“Then let’s go and see.”

Tim was silent.

“What, are you afraid?” said his cousin.

“No. Are you?”

“Don’t ask impertinent questions,” replied Rifle shortly. “Will you come?”

For answer Tim cocked his piece, and the two boys advanced over the thick grass toward the patch of dense scrub, their hearts beating heavily as they drew nearer, and each feeling that, if he had been alone, he would have turned and run back as hard as ever he could.

But neither could show himself a coward in the other’s eyes, and they walked on step by step, more and more slowly, in the full expectation of seeing a dozen or so of hostile blacks spring to their feet from their hiding-place, and charge out spear in hand.

The distance was short, but it seemed to them very long, and with eyes roving from bush to bush, they went on till they were close to the first patch of trees, the rest looking more scattered as they drew nearer, when all at once there was a hideous cry, which paralysed them for the moment, and Tim stood with his gun half raised to his shoulder, searching among the trees for the savage who had uttered the yell.

Another followed, with this time a beating of wings, and an ugly-looking black cockatoo flew off, while Rifle burst into a roar of laughter.

“Why didn’t you shoot the savage?” he cried. “Here, let’s go right through the bushes and back. Perhaps we shall see some more.”

Tim drew a deep breath full of relief, and walked forward without a word, passing through the patch and back to where the tea-jug had been left.

Here he drank heartily, and wiped his brow, while Rifle filled the mug a second time.

“You may laugh,” he said, “but it was a horrible sensation to feel that there were enemies.”

“Poll parrots,” interrupted Rifle.

“Enemies watching you,” said Tim with a sigh. “I say, Rifle, don’t you feel nervous coming right out here where there isn’t a soul?”

“I don’t know—perhaps. It does seem lonely. But not half so lonely as standing on deck looking over the bulwarks on a dark night far out at sea.”

“Yes; that did seem terrible,” said Tim.

“But we got used to it, and we must get used to this. More tea?”

“No, thank you.”

“Then I’m off.”

With the jug partly emptied, Rifle was able to run to the open part, where Man greeted him with:

“I say, what a while you’ve been. See some game over yonder?”

“No; but Tim thought there were savages in that bit of wood.”

“What! and you two went to see?”

“Yes.”

“You were stupid. Why, they might have speared you.”

“Yes; but being a sentry, Tim thought we ought to search the trees and see, and being so brave we went to search the place.”

He was pouring out some tea in the mug as he said the above, and his brother looked at him curiously.

“You’re both so what?” cried Man, with a mocking laugh. “Why, I’ll be bound to say—” glug, glug, glug, glug—“Oh, I was so thirsty. That was good,” he sighed holding out the mug for more.

“What are you bound to say?” said Rifle, refilling the mug.

“That you both of you never felt so frightened before in your life. Come now, didn’t you?”

“Well, I did feel a bit uneasy,” said Rifle, importantly; but he avoided his brother’s eye.

“Uneasy, eh?” said Man; “well, I call it frightened.”

“You would have been if it had been you.”

“Of course I should,” replied Man. “I should have run for camp like a shot.”

Rifle looked at him curiously.

“No; you wouldn’t,” he said.

“Oh, shouldn’t I. Catch me stopping to let the blacks make a target of me. I should have run as hard as I could.”

“That’s what I thought,” said Rifle, after a pause; “but I couldn’t turn. I was too much frightened.”

“What, did your knees feel all shivery-wiggle?”

“No; it wasn’t that. I was afraid of Tim thinking I was a coward, and so I went on with him, and found it was only a black cockatoo that had frightened him, but I was glad when it was all over. You’d have done the same, Man.”

“Would I?” said the lad, dubiously. “I don’t know. Aren’t you going to have a drop yourself?”

Rifle poured the remains of the tea into the mug, and gave it a twist round.

“I say,” he said, to change the conversation, which was not pleasant to him, “as soon as we get settled down at the farm, I shall vote for our having milk with our tea.”

“Cream,” cried Man. “I’m tired of ship tea and nothing in it but sugar. Hist! look there.”

His brother swung round and followed the direction of Man’s pointing finger, to where in the distance they could see some animals feeding among the grass.

“Rabbits!” cried the boy eagerly.

“Nonsense!” said Man; “they’re too big. Who ever saw rabbits that size?”

“Well, hares then,” said Rifle, excitedly. “I say, why not shoot one?”

Norman made no answer, but stood watching the animals as, with long ears erect, they loped about among the long grass, taking a bite here and a bite there.

Just then a shrill whistle came from the camp, and at the sound the animals sat up, and then in a party of about a dozen, went bounding over the tall grass and bushes at a rapid rate, which kept the boys watching them, till they caught sight of Tim making for the party beneath the tree, packing up, and preparing to continue the journey.

“Now, boys, saddle up,” cried the captain. “See the kangaroos?”

“Of course, cried Norman; we ought to have known, but the grass hid their legs. I thought their ears were not long enough for rabbits.”

“Rabbits six feet high!” said the captain, smiling.

“Six what, father?” cried Norman.

“Feet high,” said the captain; “some of the males are, when they sit up on their hind-legs, and people say that they are sometimes dangerous when hunted. I daresay we shall know more about them by-and-by.—What made you go forward, Tim, when Rifle came to you—to look at the kangaroos?”

“No, uncle; I thought I saw blacks amongst the bushes.”

“Well, next time, don’t advance, but retire. They are clever with their spears, and I don’t want you to be hit.”

He turned quickly, for he heard a sharp drawing of the breath behind him, and there was Mrs Bedford, with a look of agony on her face, for she had heard every word.

“But the blacks will not meddle with us if we do not meddle with them,” he continued quickly; though he was conscious that his words had not convinced his wife.

He went close up to her.

“Come,” he whispered, “is this being brave and setting the boys a good example?”

“I am trying, dear,” she whispered back, “so hard you cannot tell.”

“Yes, I can,” he replied tenderly; “I know all you suffer, but try and be stout-hearted. Some one must act as a pioneer in a new country. I am trying to be one, and I want your help. Don’t discourage me by being faint-hearted about trifles, and fancying dangers that may never come.”

Mrs Bedford pressed her husband’s hand, and half an hour later, and all in the same order, the little caravan was once more in motion, slowly but very surely, the country growing still more beautiful, and all feeling, when they halted in a beautiful glade that evening, and in the midst of quite a little scene of excitement the new tent was put up for the first time, that they had entered into possession of a new Eden, where all was to be happiness and peace.

A fire was soon lit, and mutton steaks being frizzled, water was fetched; the cattle driven to the river, and then to pasture, after the wagons and carts had been disposed in a square about the tent. Then a delicious meal was eaten, watch set, and the tired travellers watched the creeping on of the dark shadows, till all the woodland about them was intensely black, and the sky seemed to be one blaze of stars glittering like diamonds, or the sea-path leading up to the moon.

It had been decided that all would go to rest in good time, so that they might breakfast at dawn, and get well on in the morning before the sun grew hot; but the night was so balmy, and everything so peaceful and new, that the time went on, and no one stirred.

The fire had been made up so that it might smoulder all through the night, and the great kettle had been filled and placed over it ready for the morning; and then they all sat upon box, basket, and rug spread upon the grass, talking in a low voice, listening to the crop, crop of the cattle, and watching the stars or the trees lit up now and then by the flickering flames of the wood fire; till all at once, unasked, as if moved by the rippling stream hard by, Ida began to sing in a low voice the beautiful old melody of “Flow on, thou Shining River,” and Hester took up the second part of the duet till about half through, the music sounding wonderfully sweet and solemn out in those primeval groves, when suddenly Hester ceased singing, and sat with lips apart gazing straight before her.

“Hetty,” cried Ida, ceasing, “what is it?” Then, as if she had caught sight of that which had checked her Cousin’s singing, she uttered a wild and piercing shriek, and the men and boys sprang to their feet, the captain making a dash for the nearest gun.

Chapter Four.

“White Mary ’gin to Sing.”

“What is it—what did you see?” was whispered by more than one in the midst of the intense excitement; and just then German, who had been collecting dry fuel ready to use for the smouldering embers in the morning, did what might have proved fatal to the emigrants.

He threw half an armful of dry brushwood on the fire, with the result that there was a loud crackling sound, and a burst of brilliant flame which lit up a large circle round, throwing up the figures of the little party clearly against the darkness, ready for the spears of the blacks who might be about to attack them.

“Ah!” shouted Uncle Jack, and seizing a blanket which had been spread over the grass, where the girls had been seated, he threw it right over the fire, and in an instant all was darkness.

But the light had spread out long enough for the object which had startled Hetty to be plainly seen. For there, twenty yards away in front of a great gum-tree, stood a tall black figure with its gleaming eyes fixed upon the group, and beneath those flaming eyes a set of white teeth glistened, as if savagely, in the glow made by the blaze.

“Why, it’s Ashantee,” cried Norman, excitedly; and he made a rush at the spot where he had seen the strange-looking figure, and came upon it where it stood motionless with one foot against the opposite leg, and the tall stick or spear planted firmly upon the ground.

Click, click! came from the captain’s gun, as he ran forward shouting, “Quick, all of you, into the tent!”

“What are you doing here?” cried Norman, as he grasped the black’s arm.

“Tickpence. Got tickpence,” was the reply.

Norman burst into a roar of laughter, and dragged the black forward.

“Hi! father. I’ve taken a prisoner,” he cried.—“But I say, uncle, that blanket’s burning. What a smell!”

“No, no, don’t take it off,” said the captain; “let it burn now.”

Uncle Munday stirred the burning blanket about with a stick, and it blazed up furiously, the whole glade being lit up again, and the trembling women tried hard to suppress the hysterical sobs which struggled for utterance in cries.

“Why, you ugly scoundrel!” cried the captain fiercely, as hanging back in a half-bashful manner the black allowed himself to be dragged right up to the light, “what do you mean? How dare you come here?”

“Tick pence,” said the black. “You gib tickpence.”

“Gib tickpence, you sable-looking unclothed rascal!” cried the captain, whose stern face relaxed. “Thank your stars that I didn’t give you a charge of heavy shot.”

“Tickpence. Look!”

“Why, it’s like a conjuring trick,” cried Norman, as the native joined them. “Look at him.”

To produce a little silver coin out of one’s pockets is an easy feat; but Ashantee brought out his sixpence apparently from nowhere, held it out between his black finger and thumb in the light for a minute, so that all could see, and then in an instant it had disappeared again, and he clapped his foot with quite a smack up against his leg again, and showed his teeth as he went on.

“White Mary ’gin to sing. Wee-eak!” he cried, with a perfect imitation of the cry the poor girl had uttered. “Pipum crow ’gin to sing morrow mornum.”

He let his spear fall into the hollow of his arm, and placing both hands to his mouth, produced a peculiarly deep, sweet-toned whistle, which sounded as if somebody were incorrectly running up the notes of a chord.

“Why, I heard some one whistling like that this morning early,” cried Tim.

“Pipum crow,” said the black again, and he repeated the notes, but changed directly with another imitation, that of a peculiarly harsh braying laugh, which sounded weird and strange in the still night air.

“Most accomplished being!” said Uncle Munday, sarcastically.

“Laughum Jackamarass,” said the black; and he uttered the absurd cry again.

“Why, I heard that this morning!” cried Rifle. “It was you that made the row?”

“Laughum Jackamarass,” said the black importantly. “Sung in um bush. You gib Shanter tickpence. You gib damper?”

“What does he mean?” said Uncle Jack. “Hang him, he gave us a damper.”

“Hey? Damper?” cried the black, and he smacked his lips and began to rub the lower part of his chest in a satisfied way.

“He wants a piece of bread,” said the captain.—“Here, aunt, cut him a lump and let’s get rid of him. There is no cause for alarm. I suppose he followed us to beg, but I don’t want any of his tribe.”

“Oh, my dear Edward, no,” cried Aunt Georgie. “I don’t want to see any more of the dreadful black creatures.—Here, chimney-sweep, come here.”

As she spoke, she opened the lid of a basket, and drew from its sheath a broad-bladed kitchen knife hung to a thin leather belt, which bore a clasped bag on the other side.

“Hi crikey!” shouted the black in alarm, his repertoire of English words being apparently stored with choice selections taught him by the settlers. “Big white Mary going killancookaneatum.”

“What does the creature mean?” said Aunt Georgie, who had not caught the black’s last compound word.

“No, no,” said Norman, laughing. “She’s going to cut you some damper, Shanter.”

“Ho! mind a knife—mind a knife,” said the black; and he approached warily.

“He thought you were going to kill and cook him, aunt,” said the boy, who was in high glee at the lady’s disgust.

“I thought as much,” cried Aunt Georgie; “then the wretch is a cannibal, or he would never have had such nasty ideas.—Ob, Edward, what were you thinking about to bring us into such a country!”

“Bio white Mary gib damper?” asked the black insinuatingly.

“Not a bit,” said Aunt Georgie, making a menacing chop with the knife, which made the black leap back into a picturesque attitude, with his rough spear poised as if he were about to hurl it.

“Quick, Edward!—John!” cried Aunt Georgie, sheltering her face with her arms. “Shoot the wretch; he’s going to spear me.”

“Nonsense! Cut him some bread and let him go. You threatened him first with the knife.”

The whole party were roaring with laughter now at the puzzled faces of Aunt Georgina and the black, who now lowered his spear.

“Big white Mary want to kill Shanter?” he said to Rifle.

“No; what nonsense!” cried Aunt Georgie indignantly; “but I will not cut him a bit if he dares to call me big white Mary. Such impudence!”

“My dear aunt!” said the captain, wiping his eyes, “you are too absurd.”

“And you laughing too?” she cried indignantly. “I came out into this heathen land out of pure affection for you all, thinking I might be useful, and help to protect the girls, and you let that wretch insult and threaten me. Big white Mary, indeed! I believe you’d be happy if you saw him thrust that horrid, great skewer through me, and I lay weltering in my gore.”

“Stuff, auntie!” cried Uncle Jack.

“Why, he threatened me.”

“Big white Mary got a lot o’ hot damper. Gib Shanter bit.”

“There he goes again!” cried the old lady.

“He doesn’t mean any harm. The blacks call all the women who come white Marys.”

“And their wives too?”

“Oh no; they call them their gins. Come, cut him a big piece of bread, and I’ll start him off. I want for us to get to rest.”

“Am I to cut it in slices and butter it?”

“No, no. Cut him one great lump.”

Aunt Georgie sighed, opened a white napkin, took out a large loaf, and cut off about a third, which she impaled on the point of the knife, and held out at arm’s length, while another roar of laughter rose at the scene which ensued.

For the black looked at the bread, then at Aunt Georgie, then at the bread again suspiciously. There was the gleaming point of that knife hidden within the soft crumb; and as his mental capacity was nearly as dark as his skin, and his faith in the whites, unfortunately—from the class he had encountered and from whom he had received more than one piece of cruel ill-usage—far from perfect, he saw in imagination that sharp point suddenly thrust right through and into his black flesh as soon as he tried to take the piece of loaf.

The boys literally shrieked as the black stretched out a hand, made a feint to take it, and snatched it back again.

“Take it, you stupid!” cried Aunt Georgie, with a menacing gesture.

“Hetty—Ida—look!” whispered Tim, as the black advanced a hand again, but more cautiously.

“Mind!” shouted Rifle; and the black bounded back, turned to look at the boy, and then showed his white teeth.

“Are you going to take this bread?” cried Aunt Georgie, authoritatively.

“No tick a knifum in Shanter?” said the black in reply.

“Nonsense! No.”

“Shanter all soff in frontum.”

“Take the bread.”

Every one was laughing and watching the little scone with intense enjoyment as, full of doubt and suspicion, the black advanced his hand again very cautiously, and nearly touched the bread, when Aunt Georgie uttered a contemptuous “pish!” whose effect was to make the man bound back a couple of yards, to the lady’s great disgust.

“I’ve a great mind to throw it at his stupid, cowardly head,” she cried angrily.

“Don’t do that,” said the captain, wiping his eyes. “Poor fellow! he has been tricked before. A burned child fears the fire.—Hi! Ashantee, take the bread,” said the captain, and he wiped his eyes again.

“Make um all cry,” said the black, apostrophising Aunt Georgie; then, turning to the captain, “Big white Mary won’t tick knifum in poor Shanter?”

“No, no, she will not.—Here, auntie, give him the bread with your hand.”

“I won’t,” said Aunt Georgie, emphatically. “I will not encourage his nasty, suspicious thoughts. He must be taught better. As if I, an English lady, would do such a thing as behave like a murderous bravo of Venice.—Come here, sir, directly, and take that bread off the point of the knife,” and she accompanied her words with an unmistakable piece of pantomime, holding the bread out, and pointing with one finger.

“Don’t, pray, don’t stop the fun, uncle,” whispered Tim.

“No; let ’em alone,” growled Uncle Jack, whose face was puckered up into a broad laugh.

“Do you hear me, sir?”

“No tick a knifum in?”

“No; of course not. No—No.”

“All right,” said the black; and he stretched out his hand again, and with his eyes fixed upon Aunt Georgie, he slowly approached till he nearly touched the bread.

“That’s right; take it,” said the old lady, giving it a sharp push forward at the same moment, and the black leaped back once more with a look of disgust upon his face which gave way to another grin.

“What shame!” he cried in a tone of remonstrance. “’Tick knife in, make um bleed. Damper no good no more.”

“Well, of all the horrible creatures!” cried Aunt Georgie, who stood there full in the firelight in happy unconsciousness of the fact that the scene was double, for the shadows of the two performers were thrown grotesquely but distinctly upon the wall of verdure by their side.

Just then a happy thought struck the black, who advanced again nearly within reach of the bread, planted his spear behind him as a support, holding it with both hands, and then, grinning mightily at his own cunning in keeping his body leaning back out of reach, he lifted one leg, and with his long elastic foot working, stretched it out and tried to take the piece of bread with his toes.

A perfect shriek of laughter arose from the boys at this, and the black turned sharply to give them a self-satisfied nod, as if to say, “She can’t get at me now,” while the mirth increased as Aunt Georgie snatched the bread back.

“That you don’t, sir,” she cried. “Such impudence! You take that bread properly, or not a bit do you have.”

As she spoke she shook the knife at him, and the black again leaped back, looked serious, and then scratched his head as if for a fresh thought.

The idea came as Aunt Georgie stretched out the bread again.

“Now, sir,” she cried, “come and take it this instant.”

The black hesitated, then, slowly lowering the spear, he brought the point down to the bread and made a sudden poke at it; but the fire-hardened point glanced off the crust, and two more attempts failed.

“No,” said Aunt Georgie; “you don’t have it like that, sir. I could turn the crumb round and let you get it, but you shall take it properly in your hand. Now then, take it correctly.”

She made another menacing gesture, which caused the black to shrink; but he was evidently hungry, and returned to get the bread; so this time he advanced with lowered spear, and as he drew near he laid the weapon on the bread, and slowly advanced nearer and nearer, the spear passing over the bread till, as the black’s left hand touched the loaf, the point of the spear was within an inch of Aunt Georgie’s breast. But the old lady did not shrink. She stood her ground bravely, her eyes fixed on the black’s and her lips going all the time.

“Oh, you suspicious wretch!” she cried. “How dare you doubt me! Yes; you had better! Why, if you so much as scratched me with the point of your nasty stick, they would shoot you dead. There, take it.”

The captain felt startled, for just then she made a sharp gesture when the black was in the act of snatching the bread. But the alarm was needless; the savage’s idea was to protect himself, not to resist her, and as the quick movement she made caused the bread to drop from the point of the knife, he bobbed down, secured it almost as it touched the ground, caught it up, and darted back.

“Shanter got a damper,” he cried; and tearing off a piece, he thrust it into his mouth. “Hah, nice, good. Soff damper. No tick knifum in Shanter dis once.”

“There,” said the captain, advancing, “you have your damper, and there’s another sixpence for you. Now go.”

The black ceased eating, and looked at the little piece of silver.

“What for tickpence?” he said.

“For you—for your gin.”

“Hey, Shanter no got gin. Gin not have tickpence.” He shook his head, and went on eating.

“Very well then; good-night. Now go.”

“Go ’long?”

“Yes. Be off!”

The black nodded and laughed.

“Got tickpence—got damper. No couldn’t tick a knifum in Shanter. Go ’long—be off!”

He turned sharply, made a terrible grimace at Aunt Georgie, shook his spear, struck an attitude, as if about to throw his spear at her, raised it again, and then threw the bread high up, caught it as it came down on the point, shouldered his weapon, and marched away into the darkness, which seemed to swallow him up directly.

“There, good people,” said the captain merrily, “now time for bed.”

Ten minutes later the embers had been raked together, watch set, and for the most part the little party dropped asleep at once, to be awakened by the chiming notes of birds, the peculiar whistle of the piping crows, and the shrieks of a flock of gloriously painted parrots that were busy over the fruit in a neighbouring tree.

Chapter Five.

“How many did you see?”

It was only dawn, but German had seen that the great kettle was boiling where it hung over the wood fire, and that the cattle were all safe, and enjoying their morning repast of rich, green, dewy grass. The boys were up and off at once, full of the life and vigour given by a night’s rest in the pure fresh air, and away down to the river side to have a bath before breakfast.

Then, just as flecks of orange were beginning to appear, Aunt Georgie came out of the tent tying on an apron before picking up a basket, and in a businesslike way going to the fire, where she opened the canister, poured some tea into a bit of muslin, and tied it up loosely, as if she were about to make a tea-pudding.

“Too much water, Samuel,” she said; “pour half away.”

Sam German lifted down the boiling kettle, and poured half away.

“Set it down, Samuel.”

“Yes, mum,” said the man obediently; and as it was placed by the fire, Aunt Georgie plunged her tea-bag in, and held it beneath the boiling water with a piece of stick.

Just then the captain and Uncle Jack appeared from where they had been inspecting the horses.

“Morning, auntie,” said the former, going up and kissing the sturdy-looking old lady.

“Good-morning, my dear,” she replied; “you needn’t ask me. I slept deliciously, and only dreamed once about that dreadful black man.—Good-morning, John, my dear,” she continued, kissing Uncle Jack. “Why, you have not shaved, my dear.”

“No,” he said gruffly, “I’m going to let my beard grow.”

“John!” exclaimed Aunt Georgie.

“Time those girls were up,” said the captain.

“They’ll be here directly, Edward,” said the old lady; “they are only packing up the blankets.”

“Oh!” said the captain; “that’s right. Why, where are the boys gone?”

“Down to the river for a bathe, sir,” said German.

“What! Which way?” roared the captain.

“Straight down yonder, sir, by the low trees.”

“Quick, Jack, your gun!” cried the captain, running to the wagon, getting his, and then turning to run in the direction pointed out; his brother, who was accustomed to the captain’s quick military ways, and knowing that he would not give an order like that if there were not dire need, following him directly, armed with a double gun, and getting close up before he asked what was the matter.

“Matter?” panted the captain. “Cock your piece—both barrels—and be ready to fire when I do. The boys are gone down to the river.”

“What, are there really savages there?”

“Yes,” said the captain, hoarsely; “savages indeed. Heaven grant we may be there in time. They have gone to bathe, and the river swarms for a long way up with reptiles.”

Uncle Jack drew a deep breath as, with his gun at the trail, he trotted on beside his brother, both increasing their pace as they heard the sound of a splash and shouting.

“Faster!” roared the captain, and they ran on till they got out from among the trees on to a clearing, beautifully green now, but showing plain by several signs that it was sometimes covered by the glittering river which ran deep down now below its banks.

There before them were Rifle and Tim, just in the act of taking off their last garments, and the former was first and about to take a run and a header off the bank into the deep waters below, when, quick as thought, the captain raised his gun, and without putting it to his shoulder, held it pistol way, and fired in the air.

“Now you can shoot!” cried the captain; and again, without stopping to ask questions, Uncle Jack obeyed, the two shots sounding almost deafening in the mist that hung over the ravine.

As the captain had anticipated, the sound of the shots stopped Rifle at the very edge of the river, and made him make for his clothes, and what was of even greater importance, as he reached the bank where the river curved round in quite a deep eddy beneath them, there was Norman twenty yards away swimming rapidly toward a shallow place where he could land.

Words would not have produced such an effect.

“Now,” said the captain, panting for breath from exertion and excitement, “watch the water. Keep your gun to your shoulder, and fire the moment there is even a ripple anywhere near the boy.”

Uncle Jack obeyed, while as Norman looked up, he saw himself apparently covered by the two guns, and at once dived like a dabchick.

“Madness! madness!” groaned the captain; “has he gone down to meet his fate. What are you loaded with?”

“Ball,” said Uncle Jack, laconically.

“Better lie down and rest your piece on the edge of the bank. You must not miss.”

As they both knelt and rested the guns, Norman’s head appeared.

“I say, don’t,” he shouted. “I see you. Don’t do that.”

“Ashore, quick!” roared the captain, so fiercely that the boy swam harder.

“No,” roared the captain again; “slowly and steadily.”

“Yes, father, but don’t, don’t shoot at me. I’m only bathing.”

“Don’t talk; swim!” cried the captain in a voice of thunder; and the boy swam on, but he did not make rapid way, for the tide, which reached up to where they were, was running fast, and as he swam obliquely across it, he was carried rapidly down.

“What have I done—what does it mean?” he thought, as he swam on, growing so much excited now by the novelty of his position that his limbs grew heavy, and it was not without effort that he neared the bank, still covered by the two guns; and at last touched bottom, waded a few paces, and climbed out to where he was able to mount the slope and stand in safety upon the grass.

“Ned, old fellow, what is it?” whispered Uncle Jack, catching his brother’s arm, for he saw his face turn of a ghastly hue.

“Hush! don’t take any notice. I shall be better directly. Load that empty barrel.”

Uncle John Munday Bedford obeyed in silence, but kept an eye upon his brother as he poured in powder, rammed down a wad, and then sent a charge of big shot rattling into the gun before thrusting in another wad and ramming it home.

As he did all this, and then prised open the pan of the lock to see that it was well filled with the fine powder—for there were no breechloaders in those days, and the captain had decided to take their old flint-lock fowling-pieces for fear that they might be stranded some day up-country for want of percussion caps—the deadly sickness passed off, and Captain Bedford sighed deeply, and began to reload in turn.

Meanwhile, Norman, after glancing at his father, naturally enough ran to where he had left his clothes, hurried into shirt and trousers, and as soon as he was, like his companions, half-dressed, came toward the two men, Rifle and Tim following him, after the trio had had a whispered consultation.

“I’m very sorry, father,” faltered Norman, as he saw the stern, frowning face before him, while Uncle Jack looked almost equally solemn.

Then, as the captain remained silent, the lad continued: “I know you said that we were to journey up the country quite in military fashion, and obey orders in everything; but I did not think it would be doing anything wrong for us all to go and have a morning swim.”

“Was it your doing?” said the captain, coldly.

“Yes, father. I know it was wrong now, but I said there would be time for us all to bathe, as the river was so near. I didn’t think that—”

“No,” said the captain, sternly, “you did not think—you did not stop to think, Norman. That is one of the differences between a boy and a man. Remember it, my lad. A boy does not stop to think: as a rule a man does. Now, tell me this, do I ever refuse to grant you boys any reasonable enjoyment?”

“No, father.”

“And I told you before we started that you must be very careful to act according to my rules and regulations, for an infringement might bring peril to us all.”

“Yes, father.”

“And yet you took upon yourself to go down there to bathe in that swift, strange river, and took your brother and cousin.”

“Yes, father. I see it was wrong now, but it seemed a very innocent thing to do.”

“Innocent? You could not have been guilty of a more wild and mad act. Why would not the captain allow bathing when we were in the tropics?”

“Because of the sharks; but there would not be sharks up here in this river.”

“Are there no other dangerous creatures infesting water, sir?”

A horrified look came into Norman’s eyes, and the colour faded out of his cheeks.

“What!” he said at last, in a husky voice, “are there crocodiles in the river?”

“I had it on good authority that the place swarmed with them, sir; and you may thank God in your heart that my enterprise has not been darkened at the start by a tragedy.”

“Oh, father!” cried the boy, catching at the captain’s hand.

“There, it has passed, Man,” said the captain, pressing the boy’s hand and laying the other on his shoulder; “but spare me such another shock. Think of what I must have felt when German told me you boys had come down to bathe. I ought to have warned you last night; but I cannot think of everything, try as I may. There, it is our secret, boys. Your mother is anxious enough, so not a word about this. Quick, get on your clothes, and come on to breakfast.—Jack, old fellow,” he continued, as he walked slowly back, “it made me feel faint as a woman. But mind about the firing. We did not hit anything. They will very likely ask.”

As it happened, no questions were asked about the firing, and after a hearty breakfast, which, in the bright morning, was declared to be exactly like a picnic, they started once more on what was a glorious excursion, without a difficulty in their way. There was no road, not so much as a faint track, but they travelled on through scenery like an English park, and the leader had only to turn aside a little from time to time to avoid some huge tree, no other obstacles presenting themselves in their way.

German, the captain’s old servant, a peculiarly crabbed man in his way, drove the cart containing the tent, provisions, and other immediate necessaries; Uncle Munday came last on horseback with his gun instead of a riding-whip, driving the cattle and spare horses, which followed the lead willingly enough, only stopping now and then to crop the rich grass.

The progress was naturally very slow, but none the less pleasant, and so long as the leader went right, and Uncle Munday took care that no stragglers were left behind, there was very little need for the other drivers to trouble about their charges; while the girls, both with their faces radiant with enjoyment, cantered about quite at home on their side-saddles, now with the captain, who played the part of scout in advance and escort guard, now behind with Uncle Jack, whose severe face relaxed whenever they came to keep him company.

Hence it was that, the incident of the morning almost forgotten, Norman left the horses by whose side he trudged, to go forward to Rifle, who was also playing carter.

“How are you getting on?” he said.

“Slowly. I want to get there. Let’s go and talk to Tim.”

Norman was ready enough, and they went on to where their cousin was seated on the shaft of one of the carts whistling, and practising fly-fishing with his whip.

“Caught any?” said Rifle.

“Eh? Oh, I see,” said the boy, laughing. “No; but I say there are some flies out here, and can’t they frighten the horses!”

“Wouldn’t you like to go right forward?” said Norman, “and see what the country’s like?”

“No: you can see from here without any trouble.”

“Can you?” said Rifle; and catching his cousin by the shoulder, he gave him a sharp pull, and made him leap to the ground.

“What did you do that for?” said Tim resentfully.

“To make you walk. Think the horse hasn’t got enough to drag without you? Let’s go and talk to Sourkrout.”

“If old Sam hears you call him that, he’ll complain to father,” said Norman quietly.

“Not he. Wouldn’t be such an old sneak. Come on.”

The three boys went forward to where Sam German sat up high in front of the cart looking straight before him, and though he seemed to know that the lads were there by him, he did not turn his eyes to right or left.

“What can you see, Sam?” cried Rifle eagerly.

“Nought,” was the gruff reply.

“Well, what are you looking at?”

“Yon tree right away there.”

“What for?”

“That’s where the master said I was to make for, and if I don’t keep my eye on it, how am I to get there.”

He nodded his head toward a tree which stood up alone miles and miles away, but perfectly distinct in the clear air, and for a few minutes nothing more was said, for there were flies, birds, and flowers on every hand to take the attention of the boys.

“How do you like Australia, Sam?” said Norman, at last.

“Not at all,” grumbled the man.

“Well, you are hard to please. Why, the place is lovely.”

“Tchah! I don’t see nothing lovely about it. I want to know why the master couldn’t take a farm in England instead of coming here. What are we going to do for neighbours when we get there?”

“Be our own neighbours, Sam,” said Rifle.

“Tchah! You can’t.”

“But see how beautiful the place is,” said Tim, enthusiastically.

“What’s the good of flowers, sir? I want taters.”

“Well, we are going to grow some soon, and everything else too.”

“Oh! are we?” growled Sam. “Get on, will yer?”—this to the horse. “Strikes me as the captain’s going to find out something out here.”

“Of course he is—find a beautiful estate, and make a grand farm and garden.”

“Oh! is he?” growled Sam. “Strikes me no he won’t. Grow taters, will he? How does he know as they’ll grow?”

“Because it’s such beautiful soil, you can grow Indian corn, sugar, tobacco, grapes, anything.”

“Injun corn, eh? English corn’s good enough for me. Why, I grew some Injun corn once in the hothouse at home, and pretty stuff it was.”

“Why, it was very handsome, Sam,” said Rifle.

“Hansum? Tchah. What’s the good o’ being hansum if you ain’t useful?”

“Well, you’re not handsome, Sam,” said Norman, laughing.

“Who said I was, sir? Don’t want to be. That’s good enough for women folk. But I am useful. Come now.”

“So you are, Sam,” said Tim; “the jolliest, usefullest fellow that ever was.”

“Useful, Master ’Temus, but I don’t know about jolly. Who’s going to be jolly, transported for life out here like a convick? And as for that Injun corn, it was a great flop-leaved, striped thing as grew a ear with the stuff in it hard as pebbles on the sea-saw—seashore, I mean.”

“Sam’s got his tongue in a knot,” said Norman. “What are you eating, Sam?”

“Ain’t eating—chewing.”

“What are you chewing, then. India-rubber?”

“Tchah! Think I want to make a schoolboy’s pop-patch? Inger-rubber? No; bacco.”

“Ugh! nasty,” said Rifle. “Well, father says he shall grow tobacco.”

“’Tain’t to be done, Master Raffle,” said Sam, cracking his whip; nor grapes nayther. Yer can’t grow proper grapes without a glass-house.

“Not in a hot country like this?”

“No, sir. They’ll all come little teeny rubbidging things big as black currants, and no better.”

“Ah, you’ll see,” cried Norman.

“Oh yes, I shall see, sir. I ain’t been a gardener for five-and-twenty years without knowing which is the blade of a spade and which is the handle.”

“Of course you haven’t,” said Tim.

“Thankye, Master ’Temus. You always was a gentleman as understood me, and when we gets there—if ever we does get there, which I don’t believe, for I don’t think as there is any there, and master as good as owned to it hisself, no later nor yes’day, when he laughed at me, and said as he didn’t know yet where he was a-going—I says, if ever we does get there, and you wants to make yourself a garden, why, I’ll help yer.”

“Thankye, Sam, you shall.”

“Which I will, sir, and the other young gents, too, if they wants ’em and don’t scorn ’em, as they used to do.”

“Why, when did we scorn gardens?” said the other two boys in a breath.

“Allus, sir; allus, if you had to work in ’em. But ye never scorned my best apples and pears, Master Norman; and as for Master Raffle, the way he helped hisself to my strorbys, blackbuds, and throstles was nothing to ’em.”

“And will again, Sam, if you grow some,” cried Rifle.

“Don’t I tell yer it ain’t to be done, sir,” said Sam, giving his whip a vicious whish through the air, and making the horse toss its head, “Master grow taters? Tchah! not he. You see if they don’t all run away to tops and tater apples, and you can’t eat they.”

“Don’t be so prejudiced.”

“Me, sir—prejudiced?” cried the gardener indignantly. “Come, I do like that. Can’t yer see for yourselves, you young gents, as things won’t grow here proper?”

“No!” chorused the boys.

“Look at the flowers everywhere. Why, they’re lovely,” cried Norman.

“The flowers?” said Sam, contemptuously. “Weeds I call them. I ain’t seen a proper rose nor a love-lies-bleeding, nor a dahlia.”

“No, but there are plenty of other beautiful flowers growing wild.”

“Well, who wants wild-flowers, sir? Besides, I want to see a good wholesome cabbage or dish o’ peas.”

“Well, you must plant them first.”

“Plaint ’em? It won’t be no good, sir.”

“Well, look at the trees,” said Rifle.

“The trees? Ha! ha! ha!” cried Sam, with something he meant for a scornful laugh. “I have been looking at ’em. I don’t call them trees.”

“What do you call them, then?” said Norman.

“I d’know. I suppose they thinks they’re trees, if so be as they can think, but look at ’em. Who ever saw a tree grow with its leaves like that. Leaves ought to be flat, and hanging down. Them’s all set edgewise like butcher’s broom, and pretty stuff that is.”

“But they don’t all grow that way.”

“Oh yes, they do, sir. Trees can’t grow proper in such syle as this here. Look here, Master ’Temus, you always did care for your garden so long as I did all the weeding for you. You can speak fair. Now tell me this, What colour ought green trees to be?”

“Why, green, of course.”

“Werry well, then; just look at them leaves. Ye can’t call them green; they’re pink and laylock, and dirty, soap-suddy green.”

“Well, there then, look how beautifully the grass grows.”

“Grass? Ye–e–es; it’s growing pretty thick. Got used to it, I suppose.”

“So will our fruits and vegetables, Sam.”

“Nay, Master Norman, never. The syle won’t suit, sir, nor the country, nor the time, nor nothing.”

“Nonsense!”

“Nay, sir, ’tain’t nonsense. The whole place here’s topsy-turvy like. Why, it’s Christmas in about a fortnit’s time, and are you going to tell me this is Christmas weather? Why, it’s hot as Horgus.”

“Well, that’s because we’re so far south.”

“That we ain’t, sir. We’re just as far north as we are south, and you can’t get over that.”

“But it’s because we’ve crossed the line,” cried Rifle. “Don’t you remember I told you ever so long ago that we were just crossing the line?”

“Oh yes, I remember; but I knew you was gammoning me. I never see no line?”

“Of course not. It’s invisible.”

“What? Then you couldn’t cross it. If a thing’s inwisible, it’s because it ain’t there, and you can’t cross a thing as ain’t there.”

“Oh, you stubborn old mule!” cried Norman.

“If you forgets yourself like that, Master Norman, and treats me disrespeckful, calling me a mule, I shall tell the captain.”

“No, don’t; I’m not disrespectful, Sam,” cried Norman, anxiously. “Look here, about the line: don’t you know that there’s a north pole and a south pole?”

“Yes, I’ve heard so, sir; and as Sir John Franklin went away from our parts to find it, but he didn’t find it, because of course it wasn’t there, and he lost hisself instead.”

“But, look here; right round the middle of the earth there’s a line.”

“Don’t believe it, sir. No line couldn’t ever be made big enough to go round the world; and if it could, there ain’t nowheres to fasten it to.”

“But I mean an imaginary line that divides the world into two equal parts.”

Sam German chuckled.

“’Maginary line, sir. Of course it is.”

“And this line—Oh, I can’t explain it, Rifle, can you?”

“Course he can’t, sir, nor you nayther. ’Tain’t to be done. I knowed it were a ’maginary line when you said we war crossing it. But just you look here, sir: ’bout our garden and farm, over which I hope the master weant be disappointed, but I know he will, for I asks you young gents this—serusly, mind, as gents as has had your good eddication and growed up scollards—How can a man make a garden in a country where everything is upside down?”

“But it isn’t upside down, Sam; it’s only different,” said Norman.